Written by David Keller

This October marked the 40th anniversary of the Airline Deregulation Act, which was signed into law by President Jimmy Carter on October 24, 1978. The newly-signed legislation would bring a seismic change for US airlines, and would forever alter the course of air transportation.

This article is the first of a series focusing on the impact of Deregulation on the airline industry, which had been molded by the prior 40 years of regulation.

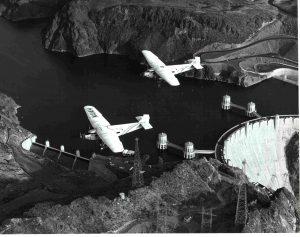

The primary government agency responsible for regulating the airlines was the Civil Aeronautics Authority (CAA) which was created in 1938. In 1940, some of the responsibilities of the CAA were split off to form a new agency, the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB). Amongst the tasks delegated to the CAB were accident investigation, and approval of fares and routes.

The goal was to create an environment that was conducive to growth of the commercial aviation industry, both by limiting the amount of competition each operator would face and by reducing aircraft accidents. This meant CAB had to balance competing directives, one to ensure competition (to prevent monopolies), and the other to limit it so airlines could operate profitably.

While accident investigations would later be turned over to the FAA (Federal Aviation Administration), the fare and route approvals would remain in the jurisdiction of the CAB. This meant that many of the important decisions affecting the growth and financial well-being of the airlines were largely in of the hands of the CAB rather than the airlines themselves.

One of the main tenants of route requests was that the requesting carrier had to show that additional competition on a given route was in the public interest. Requests to serve new routes became cases, which were subject to delays of months or years, as well as appeals by carriers hoping to limit competition on their money-making routes.

Besides attempting to promote just the right amount of competition, the CAB also made awards with an eye towards keeping individual airlines financially viable. At the conclusion of World War II, there were 15 domestic trunk carriers (not including Pan Am, which was not allowed to operate domestic services). While some of these airlines had assembled far-reaching route networks connecting larger cities over long distances, others were geographically challenged, operating short segments in a small area.

Realizing that this would make it difficult for such carriers in the long term, the CAB granted them longer routes to expand beyond their traditional regions.

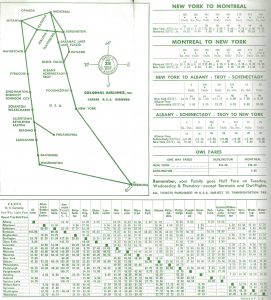

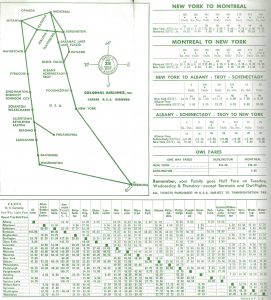

Colonial Airlines was one such airline, and in the mid-1940s was operating a route system roughly bounded by Washington, D.C., New York City and Montreal. In 1946 the carrier was given authority to serve Bermuda from both New York and Washington, D.C. to bolster its financial position.

Not having aircraft capable of providing such service delayed the start until the following year, but a few prime routes were not enough to reach a large enough scale to remain consistently profitable. The illustrated timetable dated April 29, 1956 shows the carrier’s limited route system, despite the Bermuda services. This was also the final timetable issued by Colonial, as it was merged into Eastern Air Lines on June 1st of that year.

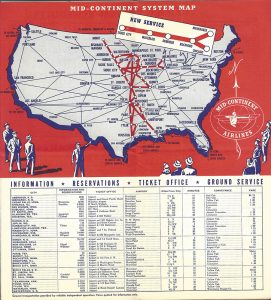

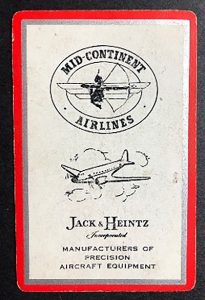

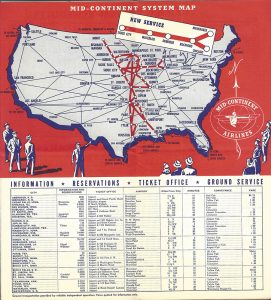

Another small trunk line, Mid-Continent Airlines, operated a limited system between Minneapolis/St. Paul and Tulsa, as depicted on the cover of the January 10, 1945 timetable. In 1947, the carrier received route extensions to the Gulf Coast, adding Houston and New Orleans to its system. The timetable dated September 24, 1950 shows additional service, this time in the form of an east-west service from Sioux City to Chicago and Milwaukee. (It appears that a separate aircraft operated one of the eastbound legs from Rockford, allowing “through” service from a single inbound destination to both Chicago and Milwaukee.)

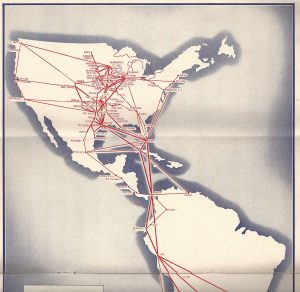

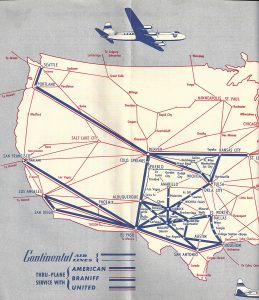

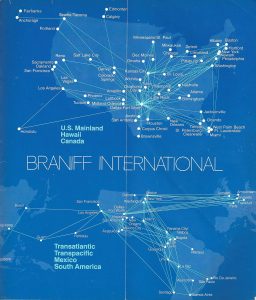

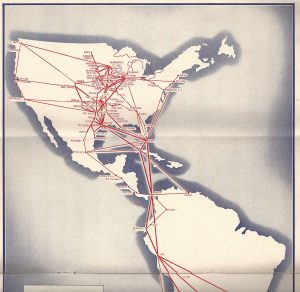

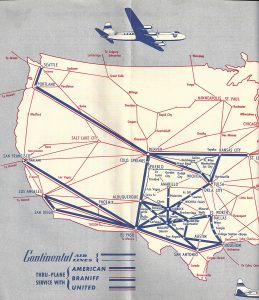

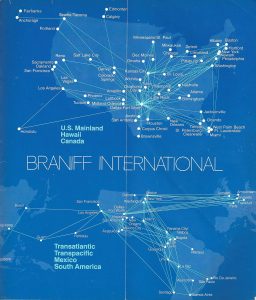

This was another case in which the new routes weren’t enough to stave off the inevitable. In 1952, Mid-Continent was acquired by Braniff International Airways, which also lacked an extensive domestic network.

However, Braniff did have international service to South America and a route system that combined well with Mid-Continent’s. As the route map from the Braniff timetable dated September, 1952 illustrates, the 2 systems dovetailed quite nicely.

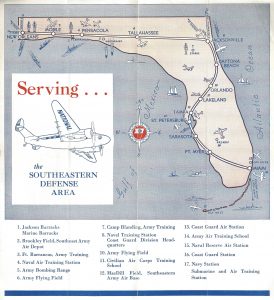

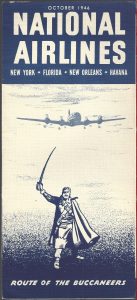

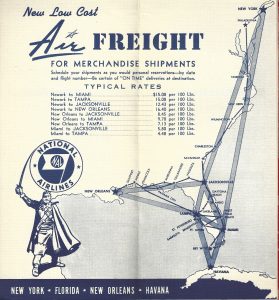

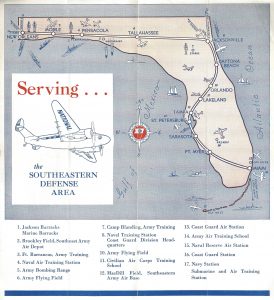

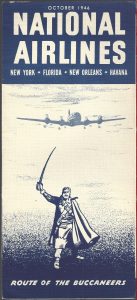

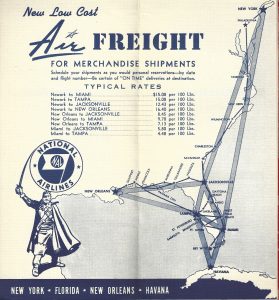

In the early 1940s, National Airlines operated a route system that snaked its way from New Orleans to Miami, as evidenced by the route map from the July 1, 1941 timetable. While a number of routes were awarded after the conclusion of the war, National was given authority to compete with Eastern Air Lines on the lucrative New York to Florida run in 1944.

The route map from the timetable dated October, 1946 shows the impact of the new services on National’s network. Although the map also includes Havana routes, that service was not yet being offered.

The new routes saved National from probable bankruptcy, and with the later addition of routes between Florida and the West Coast, kept the carrier in operation until a merger with Pan Am in 1979.

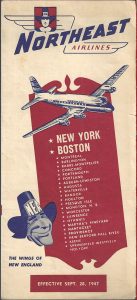

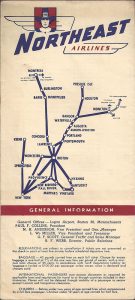

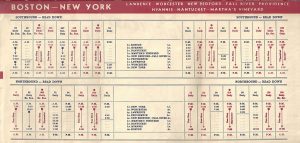

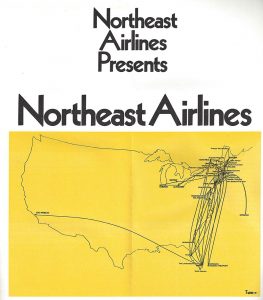

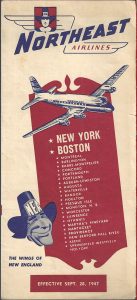

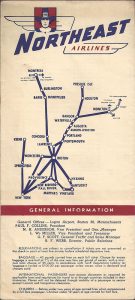

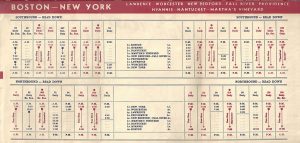

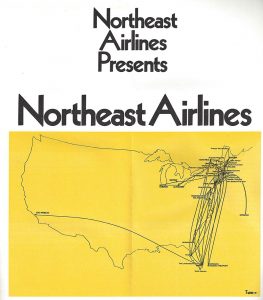

Although not in as dire a predicament as the aforementioned Colonial Airlines, Northeast Airlines also found itself with a route system wedged largely between New York City and Montreal. However, having operating rights on the busy Boston to New York route was certainly a difference maker, and the timetable dated September 28, 1947 shows 10 round trips being offered.

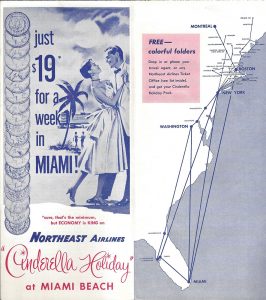

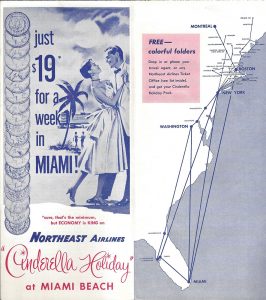

Northeast was not a recipient of long haul services immediately following the war, but did find that being confined to a small area was limiting its ability to compete with larger airlines. In 1957 Northeast began service between New York and Florida, in competition with Eastern and National. Despite many lines on the route map from the June 1, 1957 timetable connecting Florida with the northeast, the only route being operated at the time was between New York and Miami.

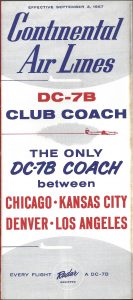

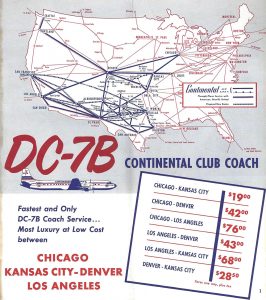

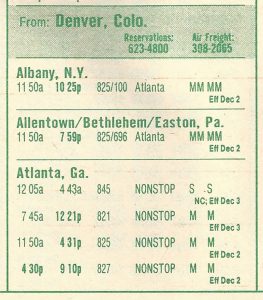

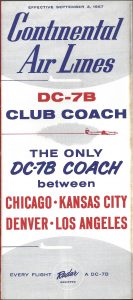

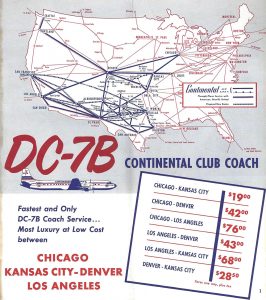

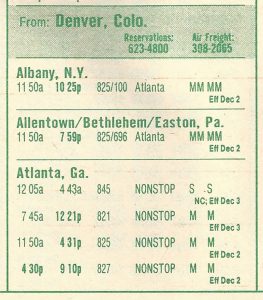

Continental Air Lines developed route system in the south central US, largely serving cities in Colorado, New Mexico, Kansas, Oklahoma and Texas. As illustrated by the route map from the timetable dated April 1, 1955, Continental had acquired local service carrier Pioneer Air Lines. Although this did add Dallas/Ft. Worth to the network, it also added many short segments to stations providing small numbers of passengers.

However, later that same year, Continental was awarded a route connecting Los Angeles and Chicago (via Denver and Kansas City), despite having no presence in either end of the route. Service began in 1957, once suitable equipment had been acquired. In this case, the route award gave the airline a huge expansion of its area of influence, and Continental steadily filled in the map with routes connecting those new cities to its traditional network.

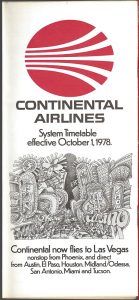

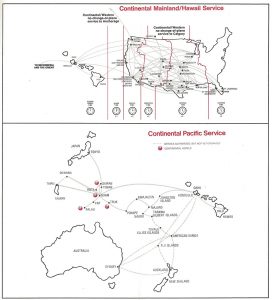

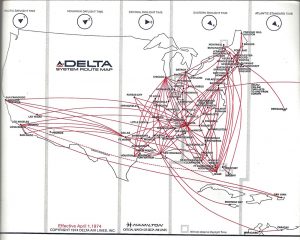

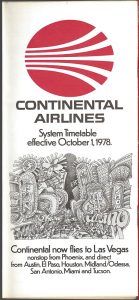

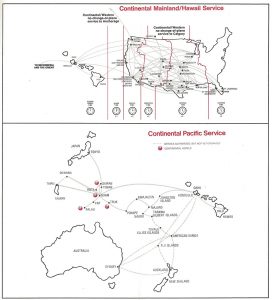

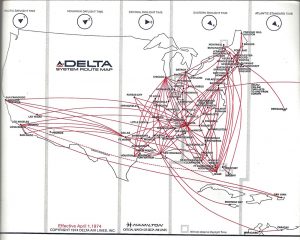

By 1964, Continental had moved its corporate headquarters from Denver to Los Angeles. The route map from the October 1, 1978 timetable shows how Chicago and Los Angeles had been incorporated into the route system. It also shows later route expansion to Florida, Hawaii and the Pacific Northwest.

Another example of the CAB’s impact on American aviation was the creation of feeder, or local service, airlines. This was an attempt to bring air service to still more cities than were part of the trunk airlines’ route network. These airlines required “public service” subsidies to remain financially viable, given the nature of their stated mission.

Another example of the CAB’s impact on American aviation was the creation of feeder, or local service, airlines. This was an attempt to bring air service to still more cities than were part of the trunk airlines’ route network. These airlines required “public service” subsidies to remain financially viable, given the nature of their stated mission.

Over 2 dozen local airlines received certificates to start service, but some never left the ground, and others failed after a short period of operation or were merged into other carriers.

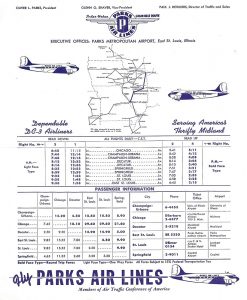

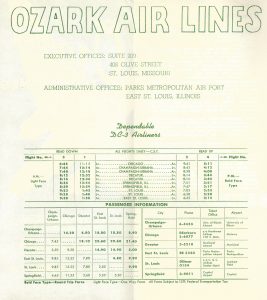

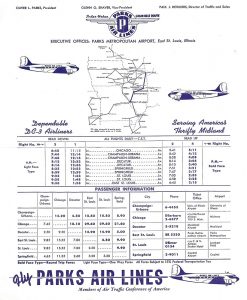

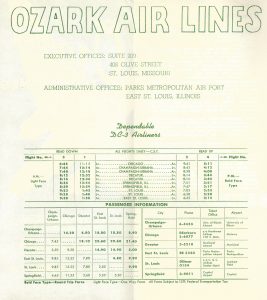

Parks Air Lines was one of those local carriers that failed to launch. The airline issued several timetables in the summer of 1950, including the illustrated August 1, 1950 issue. But the company was unable to get started and its routes were awarded to Ozark Air Lines and Mid-Continent Airlines. (In fact, the new Mid-Continent routes to Chicago and Milwaukee previously mentioned were originally intended to be operated by Parks.)

Ozark Air Lines inaugurated service on September 26, 1950. As the timetable from that date illustrates, the flight numbers, times, and even local phone numbers were unchanged from those in the Parks timetable.

By 1956, just over 1 dozen local service airlines remained. Besides opening service to new cities, these carriers also inherited services that the trunk carriers wished to shed so they could retire their DC-3s and concentrate on more profitable routes.

As these airlines grew, they began to explore acquisition of aircraft larger than the DC-3, which made of the vast majority of the combined local airline fleet in the mid-to-late 1950s. The CAB was not particularly fond of this idea, as larger aircraft would require additional subsidies to operate profitably on routes that were largely low density.

Despite this, several airlines did acquire larger equipment beginning in the mid-1950s. As this now gave those carriers equipment that was more on par with the larger airlines, they felt prepared to operate routes that had profit-making potential. This did have an appeal to the CAB (and government in general), since subsidies (although rather modest in dollar amount) were always a hot button political issue. Convairs, Martins and F27s were incorporated the various airlines’ fleets by the early 1960’s.

However, while the locals added those types, the trunks were busily reequipping with pure jets, which still left the locals behind in the technology curve. But with the introduction of “small” jets in the mid-1960s, the locals were able to make a sound case to compete on routes previously in the domain of the trunk carriers.

BAC 1-11s, DC-9s and 737s provided the ability to both operate from shorter runways than the first generation 4-engine jetliners, and also to make a profit on short route segments. The locals placed orders, and all (with the exception Lake Central) were operating jets by the end of 1967. With the prospect of local carriers truly being able to compete on profitable routes, coupled with the opportunity for those services to reduce subsidies required, those airlines finally began to receive such route authorization.

In the late 1960s and early 70s, the CAB awarded numerous routes the local carriers, which were eager to show off their shiny new jets, and shed their “puddle jumper” image. And as the routes came, so did orders for additional jets.

Generally, these awards were a combination of new nonstop authority between cities already served by the carrier, and new routes outside of their traditional service area.

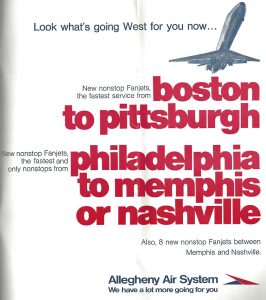

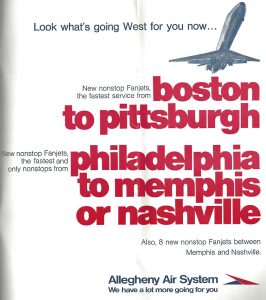

The Allegheny Airlines timetable dated April 27, 1969 promotes new services to Nashville and Memphis from Philadelphia. (Both of those cities had recently been added to the system with service to Pittsburgh.) In addition to these new cities, Allegheny was operating non-stops from Pittsburgh to points already in the network, such as New York City, Boston, and Louisville.

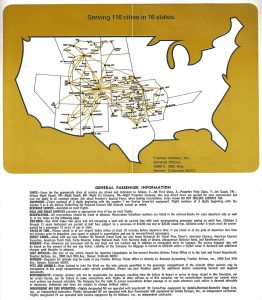

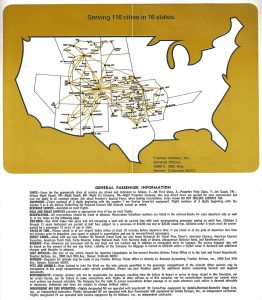

Frontier Airlines didn’t wait for the twin engine jetliners, as the carrier placed an order for the trijet 727. The timetable dated July 7, 1969 shows the airline operating jets (which were a mix of 727s and 737’s at that point), on a number of nonstop routes from Denver. Service was offered to Las Vegas (a new station), as well as Dallas, Kansas City, Phoenix, St. Louis and Salt Lake City.

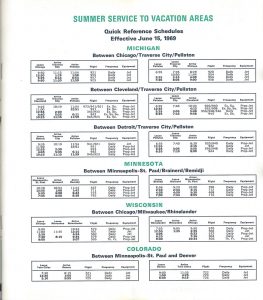

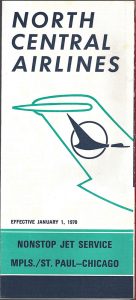

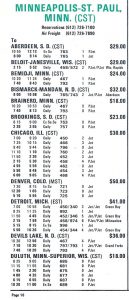

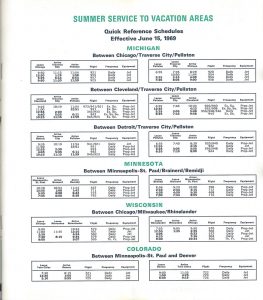

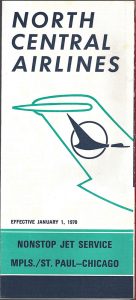

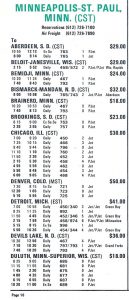

The two illustrated North Central Airlines timetables, from June 15, 1969 and January 1, 1970 show the inauguration of service to a new destination, Denver, as well as between the airline’s 2 largest stations, Minneapolis/St. Paul and Chicago. North Central would soon receive additional authority to operate from Milwaukee to both New York and several Ohio cities, further expanding the network.

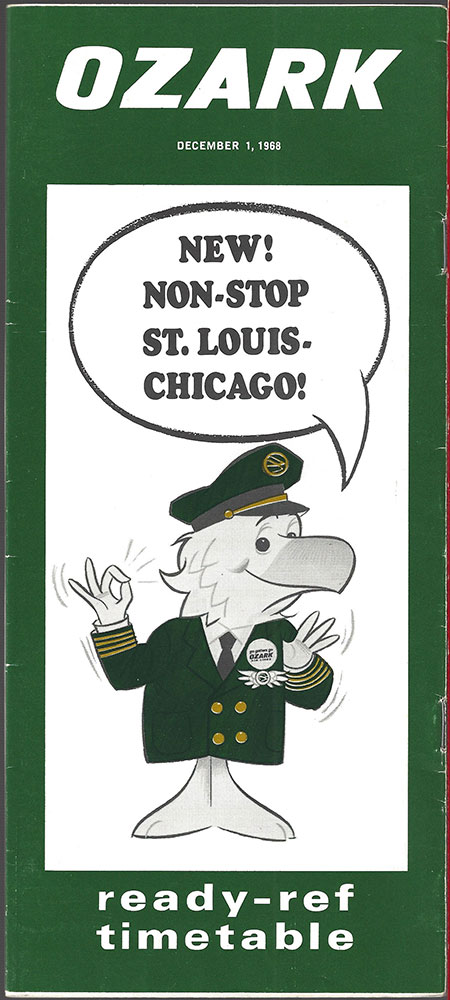

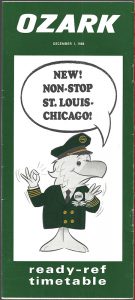

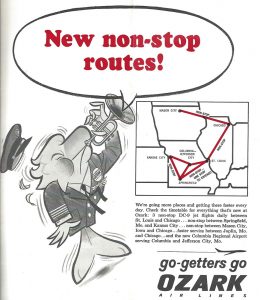

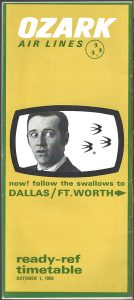

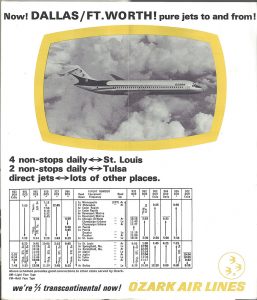

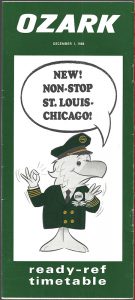

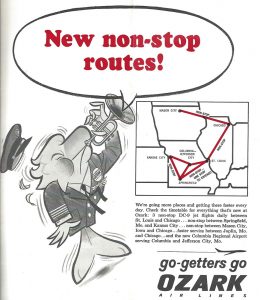

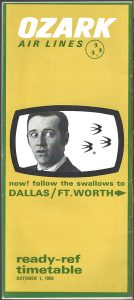

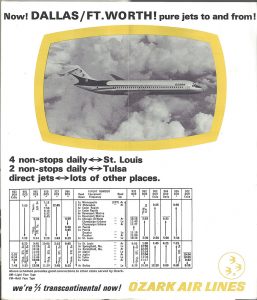

Ozark Air Lines received similar routes, as promoted on the covers of timetables dated December 1, 1968 and October 1, 1969. The 1968 issue touts service between the carrier’s 2 largest stations, Chicago and St. Louis, while the 1969 timetable features a clean-shaven George Carlin hawking new nonstop service from St. Louis to Dallas/Ft. Worth. By this time, Ozark had already received new authority to serve some of the most popular destinations for new service, Denver, New York City, and Washington, D.C..

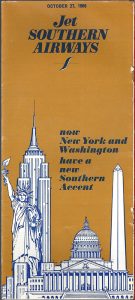

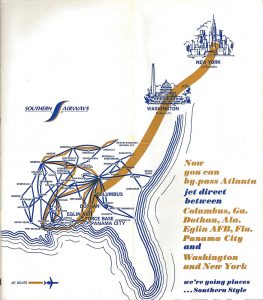

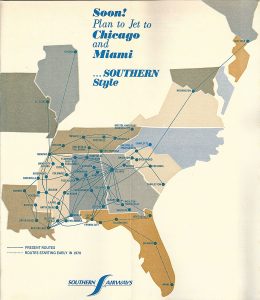

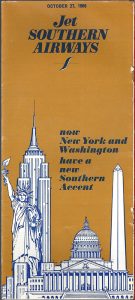

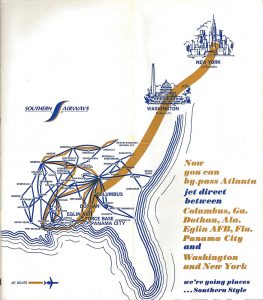

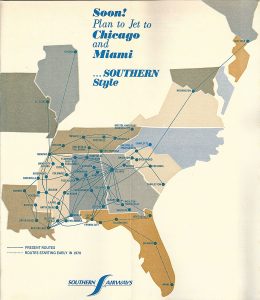

Southern Airways’ timetables dated October 27, 1968 and January 1, 1970 show that most of this carrier’s new nonstop authority was to serve cities outside of its local service area. The 1968 issue promotes new service to Washington, D.C. and New York City from Columbus, Georgia, Dothan, Alabama and Eglin AFB in Florida, thus eliminating the need to connect in Atlanta. The route map of the 1970 timetable shows service had already been started to St. Louis, with Chicago and Florida routes beginning shortly. (Florida was one of the few areas in the country that didn’t have a local service operator providing service throughout the state.)

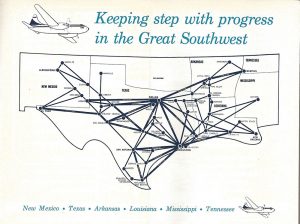

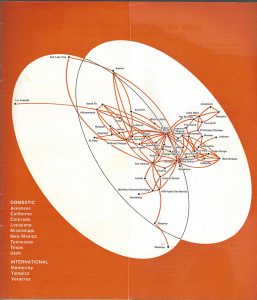

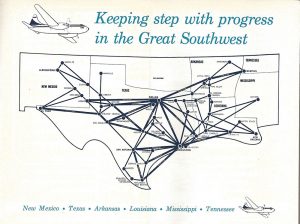

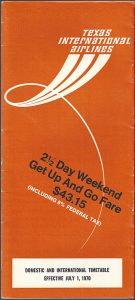

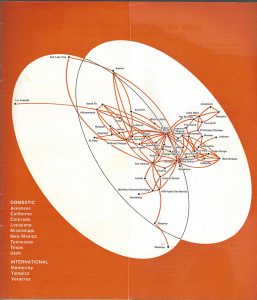

In Trans-Texas Airways’ timetable dated July 1, 1966, the airline was operating primarily to cities in Texas and bordering states. A number of the routes in West Texas and New Mexico were being operated by Continental a decade prior.

By the summer of 1970, the route map sported routes to Denver, Salt Lake City, Los Angeles and Mexico. To capitalize on its expanded presence, TTA had changed its name to Texas International Airlines the previous year.

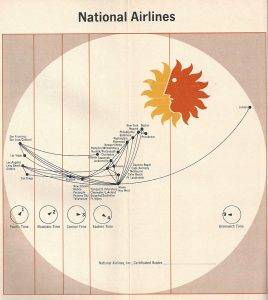

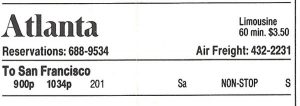

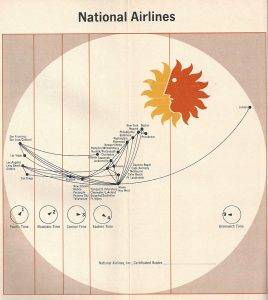

Some of the CAB’s attempts to strengthen weaker airlines were questionable at best. On October 1, 1969, National Airlines began service between San Francisco and Atlanta. One look at the route map, and it’s difficult to see how this was going to pan out, even in the relatively tame competitive environment of the day.

National started with 2 roundtrips on the route, then pared it back to 1 the following year. It appears the service was suspended in the mid-1970s, with the single roundtrip returning in the summer of 1976. By late 1976 the operation was twice weekly, which then dropped to a single weekly frequency. (In addition to needing CAB approval to start new service, there were also rules on ending service. An airline wanting to discontinue a route would sometimes reduce the frequency to only 1 per week as they petitioned to stop service altogether.)

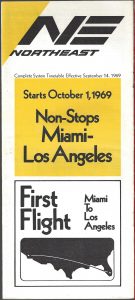

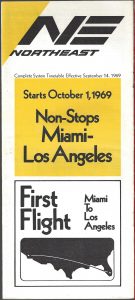

In another attempt to assist the oft-ailing Northeast Airlines, the carrier was awarded the highly coveted Miami to Los Angeles route, also with an October 1, 1969 start. Once again, the route map reveals this to be a questionable decision, although perhaps not as much as the fact that Northeast’s longest range type was the 727-100, which was not designed for transcontinental service. The airline did have Lockheed L1011s on order, which could certainly make that journey, although the ability to pay for them was in serious doubt.

Northeast was evidently confident of their ability to turn a profit on the route, and started service with 3 daily roundtrips. That was reduced to 2 by early 1971, and a single roundtrip a few months later. Northeast finally found its badly-needed merger partner in the form of Delta Air Lines the following year, but Delta did not receive the Miami-Los Angeles route as part of the merger. The route showed up on Delta’s route maps for several years as “Subject to CAB approval”, and was eventually awarded to Western Airlines in 1976.

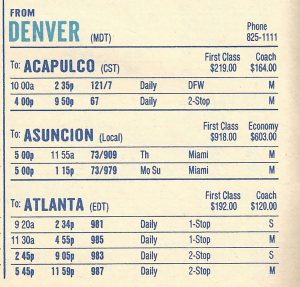

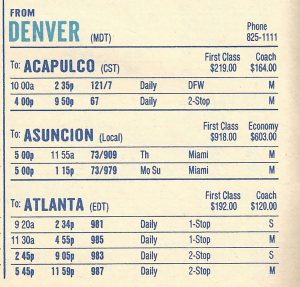

One of the last major route cases the CAB handled was finalized in the summer of 1977 and involved service between Denver and the Southeast. Incredibly, until late July of 1977, it was not possible to fly nonstop between Denver and Atlanta, which even then were 2 of the largest hubs in the US. The only through service was a long-running Eastern-Braniff interchange service which operated 4 daily services via Memphis.

The CAB designated Delta and Braniff to receive nonstop authority on the route. Delta was a natural fit, given its strength in Atlanta, but Braniff was not a major player in either market. Both carriers started service on July 28, 1977 with 4 daily non-stops. This brought an immediate termination of the interchange service through Memphis.

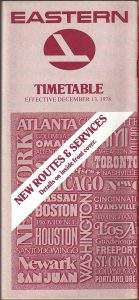

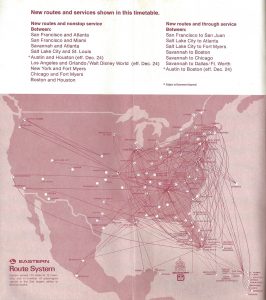

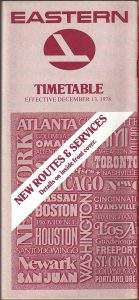

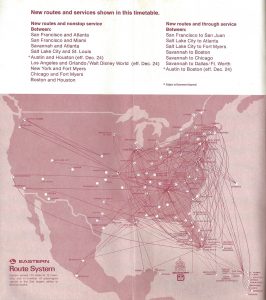

Eastern attempted to maintain the 4 daily frequencies on the Memphis-Atlanta segment (which was its only route from Memphis), but very quickly ceded the market to Delta, which had a sizeable operation there. The September 6, 1978 shows only a single weekly frequency on the route and by the December 13, 1978 issue, service was terminated, leaving Memphis as an unnamed point on the route map,

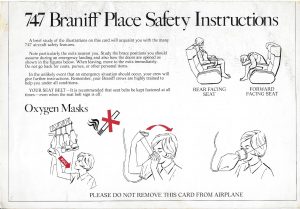

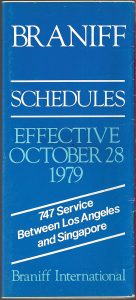

Braniff was struggling with the new route even before Deregulation, cutting back on frequencies, while Delta added new ones. By late 1979, Braniff was down to a single nonstop plus several one-stop flights, and in October the route was dropped altogether along with many others as Braniff had put itself into a dire financial situation. The other half of the old interchange service, Eastern Airlines, filled the void, starting flights in December with 4 daily non-stops.

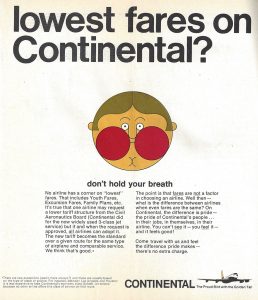

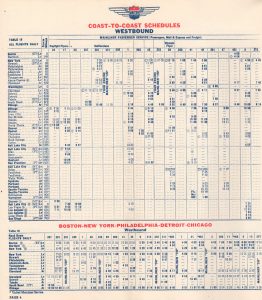

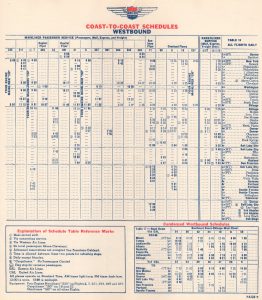

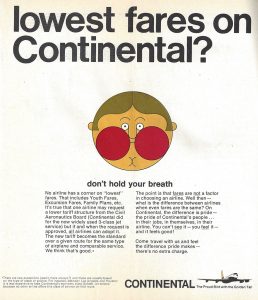

As mentioned, the CAB also approved fares the airlines could charge for each level of service. Essentially, the fare for a given service (First Class, Coach, etc.) was the same on a specific route regardless of which airline was offering the service. Continental Airlines has an explanation of this concept in the gatefold of their timetable dated June 30, 1966.

For those who don’t remember pre-deregulation days, it’s probably difficult to grasp that average load factors in the 1960s and 70s were generally in the low to mid 50 percent range. Fares were set such that airlines only needed to fill just over half of their seats to make a profit, sometimes even less.

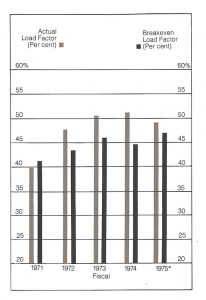

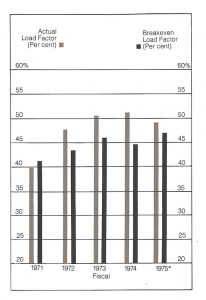

As detailed in the annual reports of National Airlines and Texas International Airlines, it was not unusual for airlines to transport more cold seats that warm ones over the course of an entire year. National’s chart from their 1975 annual report shows their annual load factor exceeding 50% in only 2 of the 5 years encompassing 1971 through 1975. For one of those years, 1971, the load factor was approximately 40%.

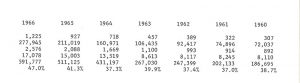

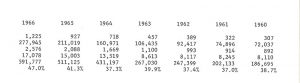

Texas International Airlines’ 1969 statistics illustrate that they never exceeded a 50% load factor during the 1960s, and early in the decade, those load factors were actually in the upper 30s. Being a local service carrier, much of the lack of revenue from paying passengers was covered by federal subsidies.

This meant that the airline industry, having fare levels set to ensure profits with half empty planes, and being generally protected from unbridled competition, were not the lean and mean organizations they would need to be in order to prosper in a deregulated environment.

The US airline industry arrived at the transition between a regulated industry and a deregulated one with 11 trunk carriers, 8 local service carriers, a few small airlines in Alaska and Hawaii, a number commuter lines, and intrastate carriers in several states (which were not regulated by the CAB as long as they only served destinations within a single state).

Some airlines were confident in their ability to thrive in a deregulated environment and wholeheartedly supported the Act’s passage. Others, shackled with high costs and fearing additional competition siphoning profits, were opposed, while some airlines had mixed feelings.

Regardless of each airline’s opinion on the matter, they were all thrust into the brave new world on October 24, 1978.