Musings from a Passenger’s Seat: Pleasant Memories ~ Flight Segment 2

Written by Lester Anderson

Am I getting old?

I think of my years of travel often, and with great enjoyment. It sobers me to realize that virtually every airplane I flew on during my business flying career has most probably been sent to the aircraft graveyard to be scrapped. Many great memories now in the recycle stream.

I sat next to who?

America West was a relatively new airline and when they started their frequent flyer program, so of course I joined. Just after I got my card, I had a business trip that took me to Phoenix and back. On the way back I was on the red-eye. Waiting in the gate area, they are calling for volunteers because they need the seats. Then they call my name. At the podium I was told I was being upgraded to First. I thanked them but asked why me since I don’t fly America West that much. They said I as the only one in Economy in their frequent flyer program so they would reward me. I boarded and was in the window seat in the last row of First. There was someone next to me, and during the flight the cabin staff were offering him drinks and amenities. Since I was an upgrade not a full fare First I thought little of it (plus at 11:00 I don’t want a lot). As we started to land, a few more cabin crew came by and asked for (and got) autographs. I have no idea who this gentleman was (my guess a singer that I did not know), but he certainly made an impression on the flight crew. I remember I did not want him to think I was ignoring him, so I just wished him a great day, and he said thank you and that was it.

With my travel volume I got my share of normal upgrades to First where the famous almost always fly. And at the airport, celebrities are often given access to the Airline clubs. I saw Phyllis Diller in the Eastern Ionosphere club in Newark, and Cher in the United club in Newark. I am sure there were celebrities on the flights that I did not know who they were, but two I remember were Dr. Joyce Brothers who sat in the seat in front of me on one flight (and was both beautiful and very petite) and on another flight James Doohan sat diagonally across. My personal rule was never to bother anyone famous I saw, but after I landed in LA, Mr. Doohan was met by someone from “the studio” and had him wait for the car. I broke my rule and just thanked him for giving me and his fans such enjoyment as he played Scotty in Star Trek. He smiled and said Thank You.

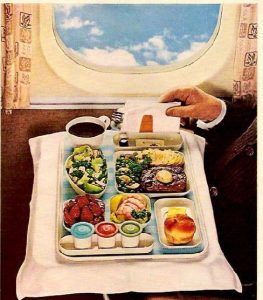

Meals

Today any meal on an airplane is something special (or at least unusual). Back in the day, both First and Economy got meals. On transcontinental United flights that involved a hot breakfast about 40 minutes after takeoff, and a box lunch an hour before landing. The service carts were well designed with a heated plate that went under the hot meal dish on each tray. I found that no matter how they served eggs, they never survived well. A better bet was the pancakes rolled around apple pie filling. Unfortunately eggs were on 80% of the flights, pancakes or something else was 20%.

My favorite snack of all times was on Eastern. They had a Disposable clear plastic tray and Saran wrapped an apple; a packet of cheddar cheese, packets of crackers, and a knife (plastic) and napkin. The apple was always crisp, and the amount of food was perfect for a mid-afternoon snack. And at the end of the meal, they did collect (and recycle) the plastic trays.

When the airlines tried to save a little on flights like Newark to Florida they would give a box of cereal, a container of 2 milk and a banana to each passenger. That was better than a lot of the meals I am sure cost the airlines much more money.

The Flying Nosh

In the lucrative NYC-DCA market (where the one-hour flight could often cost $300) New York Air had a “flying Nosh” service where they promoted the service by giving you a fabric bag with a bagel, a packet of cream cheese, and a small container of jelly. The bags were great because you could keep them. My children used them as lunch bags for a while. The other thing about NY Air was they had MD-80s in their fleet. Entering the MD-80 through the main cabin door you could easily see and read (because the line moved slowly) the metal plate which gave the serial number of the aircraft, and the manufacture date. I recall most of those on which I flew were in the 1983 vintage.

And they did compete with the Eastern Air-Shuttle of guaranteed seat fame. So they booked multiple plane loads on the same flight. And when you were at the gate area, they would call your flight and say if you have the grey boarding pass go to this gate, if you have the red boarding pass, go to this gate. This system worked very smoothly (at least every time I experienced it).

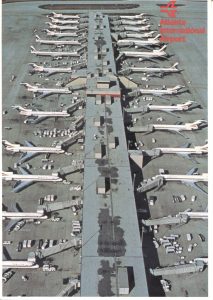

Denver International Airport

In the 1990’s Denver had a massive building program to replace Stapleton Airport with DIA, Denver International Airport. If you travelled on United or Continental, you were often changing planes in Denver as it was a major hub. Stapleton was showing its age and there was (especially in the business traveling public) an excitement of a new and more passenger friendly terminal in a major hub. Like any program there was a lot of publicity and promised made and fact sheets about the new terminal left in the airline clubs and the gate areas. We saw artist conceptions and early photographs of the “circus tent” roof structures of the main terminal. Originally scheduled to open in the fall of 1993, there was delay after delay. We frequent travelers joked that DIA stood for “Done in August” but August came and went and we were still at Stapleton. When it finally opened in February 1995, it was grand. Because I controlled my own flights when traveling, my first trip after it opened, I scheduled a 3 ½ hour layover between flights and I went through the entire Airport. And I will say it was worth the wait.

A PDF of the souvenir opening booklet is available at www.flydenver.com. If your search for it is not successful, google inside dia souvenir guide and it will link you to download the PDF.

How to Manage your Business Flights

My first job after teaching was ideal for someone with a love for commercial aviation. My cubicle was right outside of the corporate travel office (and of course I made friends with the staff to the point where they showed me some of the workings of the Sabre reservation system), and I showed them (because we subscribed to the Lockheed database online services), the OAG online database. Both systems would give you flight data and seat availability for each fare class (I remember Sabre would tell you up to 7 seats available, and I recall OAG only told you if 4 were available. And of course you could search for the best fares. Corporate travel was run by a travel agency, and Phil (my key contact) told me that I could see virtually anything he could see on his Sabre terminal on my desktop computer and the OAG database. And he concluded that travel agents were dinosaurs.

The key to getting any corporate travel department to like you was making their job easy. Go in with a set of flights have space on them and a fare basis that was close to the least expensive ones. Once you established you knew what you were talking about and you were able to prove it, I never had a problem with getting flights I wanted. This gave me the ability to fly the airplanes I liked and the airlines I liked – or when feeling adventurous, flying new ones I had not experienced before. And I was successful in doing that in every company for which I worked thereafter.

I only wish I had done as well in booking of hotels.

Boeing

I have one claim to fame (very minor to everyone else). While I was still teaching I worked part time for a computer programming company. I programmed and consulted on the earliest microcomputers (Apple II, TRS-80, and Commodore Pet). This was about 3 years before IBM released the first PC.

Boeing Computer Services (a computer division of Boeing Airplane Company) wanted to learn about these new microcomputers and what they could do (they typically worked with large mainframe computers). I got the assignment and gave a half day lecture/discussion of these new small computers. For weeks thereafter (and even to this day when I think of it) I float on air thinking that I had information that was of interest to the Boeing Company and they paid my employer to have me share it with them.

Interesting Airplane Information

I am not a pilot, nor am I an airplane mechanic. I never went to formal school to learn about airplanes. I read as many books and magazines about the airplanes I could find.

But a lot of my best information comes from a source most people do not use.

For example, did you know that:

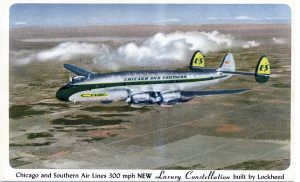

The Lockheed Constellation had its emergency life rafts stored in the wings, so in case of a water landing they would pop out. This was both fast and removed requirement of pushing rafts out doors or windows.

The 727 has pitot tube sensors to gauge the airspeed of the aircraft on the tail assembly. This information is used to control how much force is needed by the pilots on the cockpit flight controls for the tail surfaces.

Facts like these as well as a wealth of information about how airplanes work (and sometimes don’t) area found in the US Government published Aircraft Accident Reports. In the 30’s it was the Department of Commerce. In the 40’s thru the 60’s it was the CAB (Civil Aeronautics Board), and now the NTSB. The government reports are not grim stories of crashes (as some books are), but are scientific, methodical studies of what happened and why and how to prevent it from ever happening again. And they were a great educational resource on how airplanes were designed, assembled, and maintained.

I started being interested when a United DC8 and TWA Constellation crashed over New York in 1960 (I was 13). I had lived on Staten Island not far from where the TWA crashed, and my great aunt lived in Brooklyn not far from where the United crashed. My parents (probably rightly) would not allow me to go and try to see the sites, but there were a lot of newspaper pictures. I was interested in how they could figure out what happened from this mess of wreckage.In those days you needed to write to the CAB and ask them to mail you a copy. And they did find and mail me about 275 of them over the years I was in high school and college. Now historic and current reports are available as PDFs online for download (most Wikipedia entries about a crash link to the AAR in the footnotes).

The science of accident investigation has truly advanced in the 90 years of reports that I have read (my earliest was a 1936 crash of a Transcontinental and Western DC-2). They have gone from typed, mimeographed pages to PDFs that are almost books, many with color photos or illustrations where needed.

And if anyone were to ever be concerned about flying being safe, todays’ reports confirm that many things must go wrong all at once for an accident to happen.

Lester Anderson

I hope you enjoyed my flights down memory lane as much as I did. I am sort of out of things to say, but if Shea has any ideas on future articles to which I can make a positive contribution, you may hear from me again.