airlines,Safety cards

HISTORY OF SAFETY CARDS, Part 7: An Examination of Subjects

By Fons Schaefers

Introduction

Which subjects are shown on safety cards? There is a minimum set of mandatory subjects appearing on all safety cards. Additionally, there are subjects many airlines add, and some only a few carriers choose. Particularly the latter appetizes collectors who seek unique samples. This article is a structured examination of the common items, complemented with examples of those one-offs.

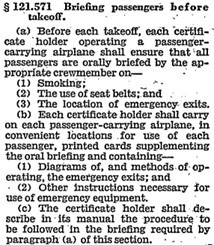

The mandatory items can be divided into those that apply to each flight (the routine subjects) and those for emergencies only.

Routine Subjects

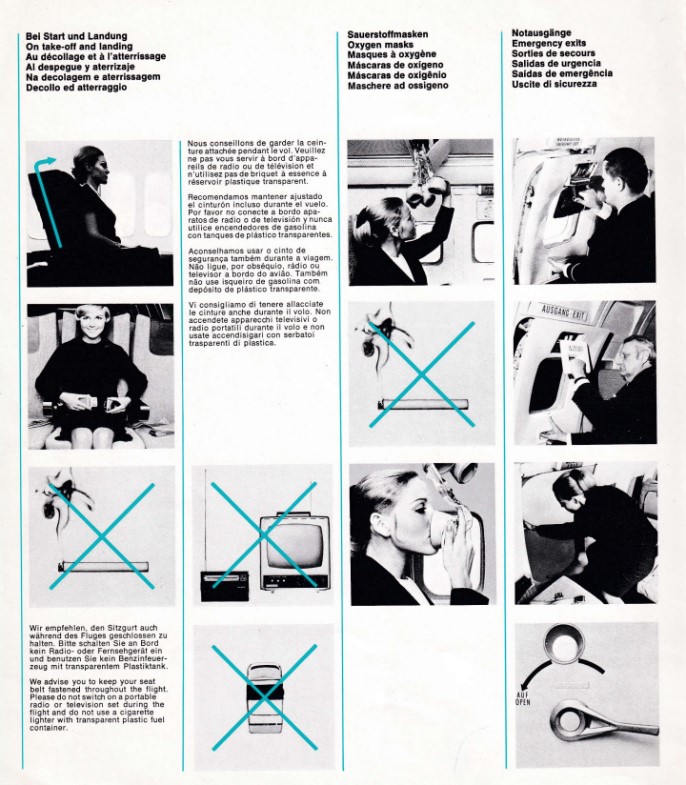

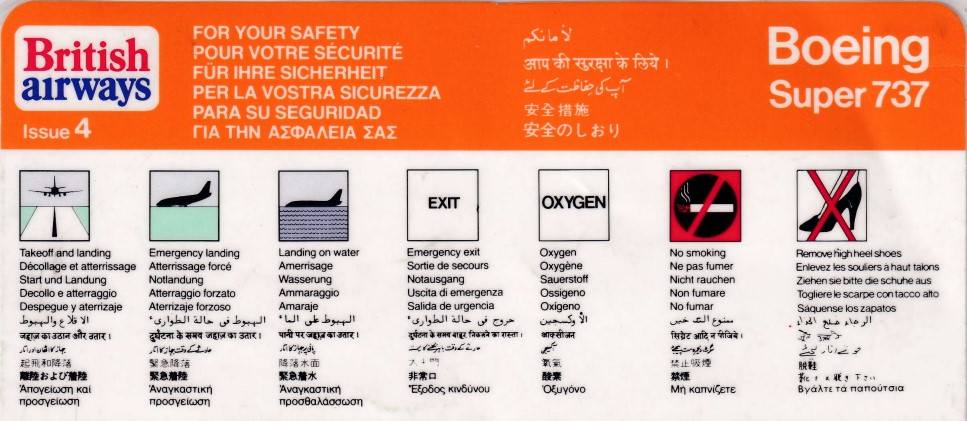

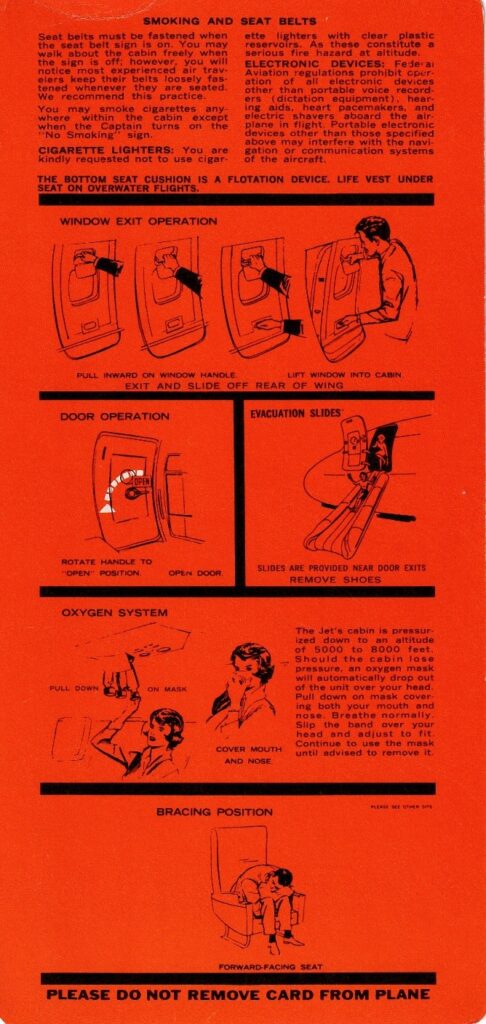

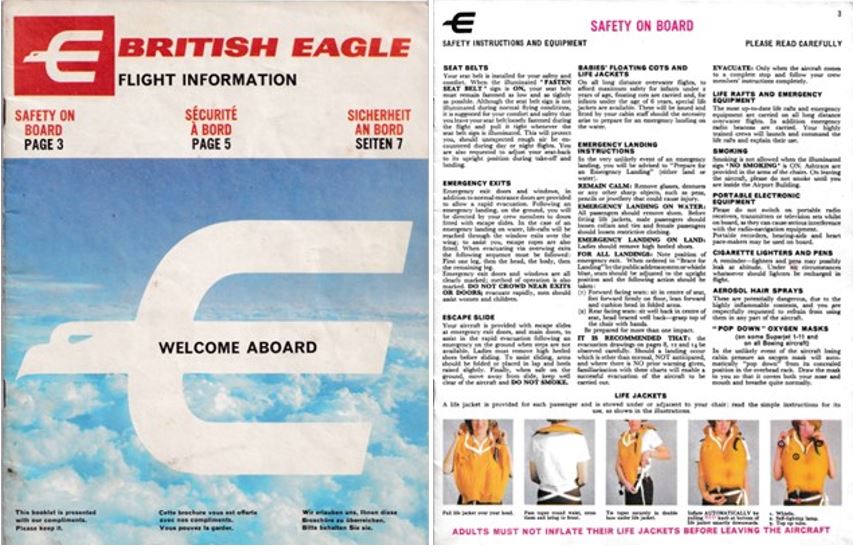

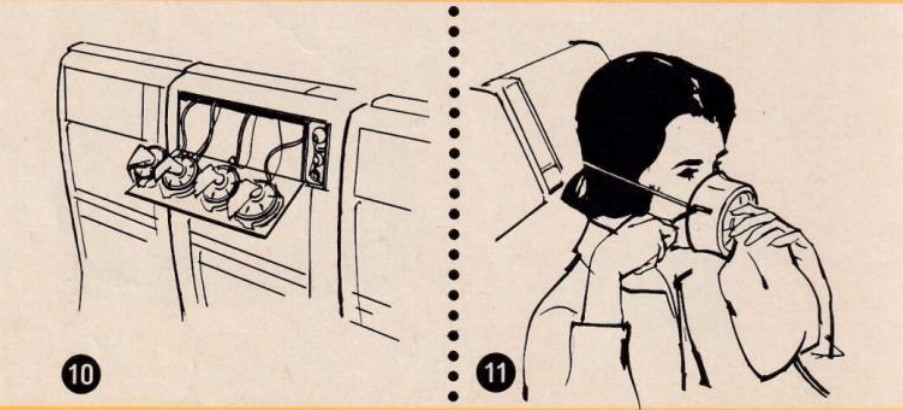

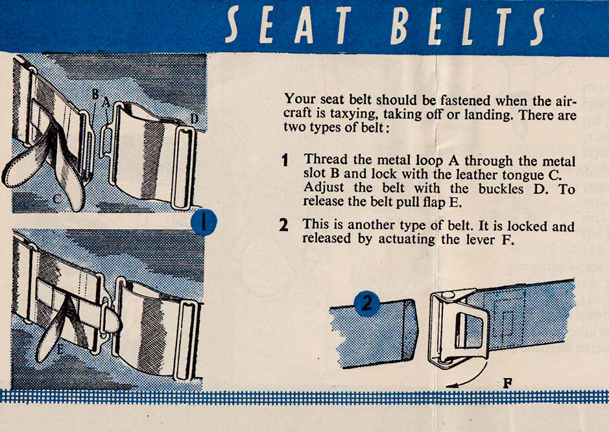

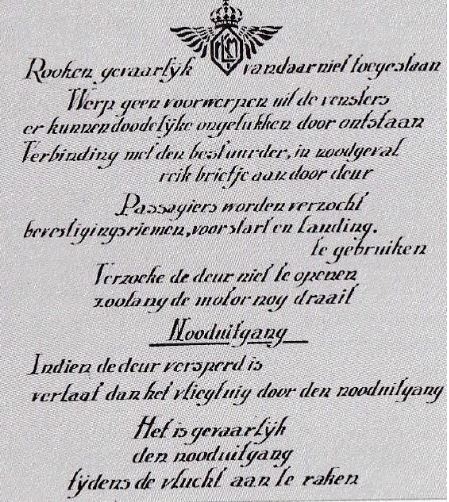

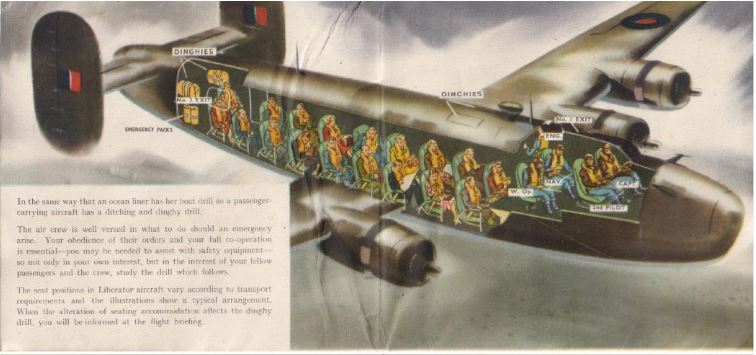

The routine subjects often appear first on the cards. They include baggage stowage, seat belt use, and subject to much recent development, the use of electronic devices. Some airlines add regulations about not smoking, specifically in lavatories.

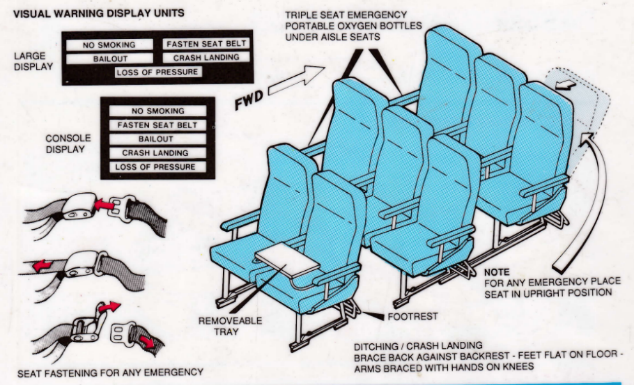

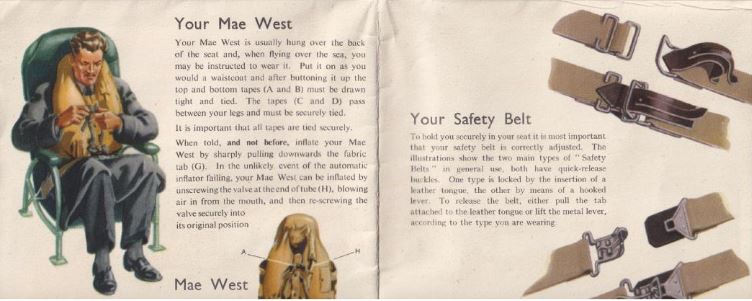

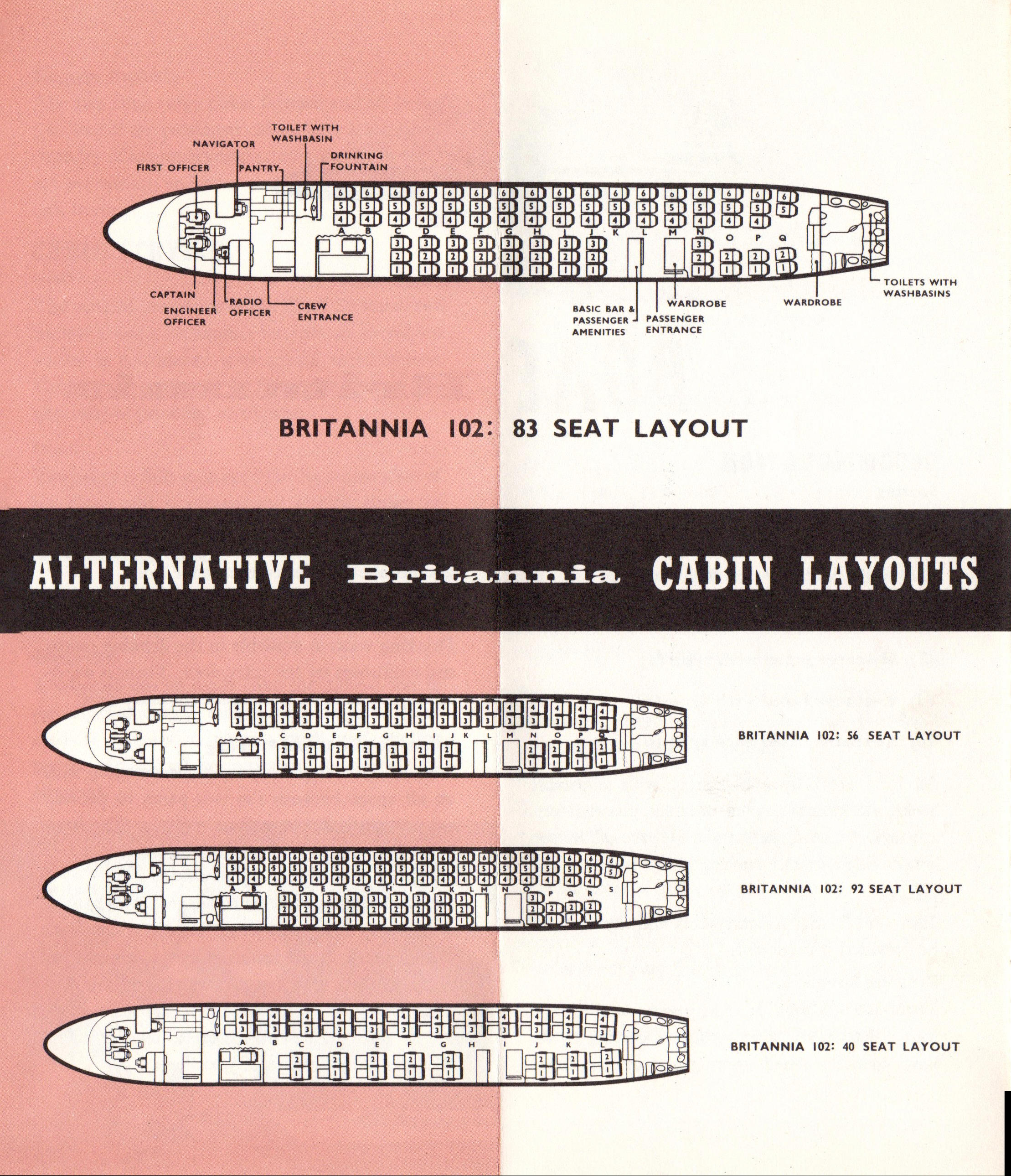

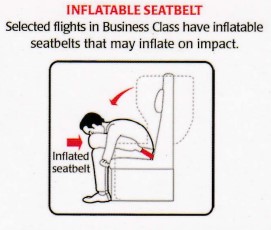

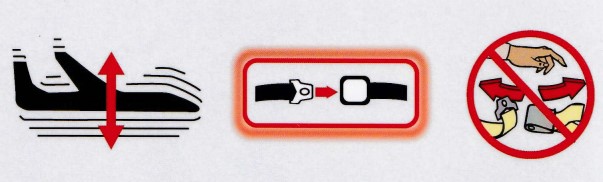

Almost all cards show baggage stowage under seats, and some also show putting it in overhead compartments. The fastening and unfastening of seat belts is a standard item on all cards. Recent restraining developments now found on cards are shoulder harnesses and seatbelt-mounted airbags. They result from stricter safety regulations introduced since the late 1980s, generally known as the “16 g” rules.

Some airlines add instructions to keep the safety belt fastened, or fasten it, during turbulence. Canadian North uses a telling symbol for turbulence.

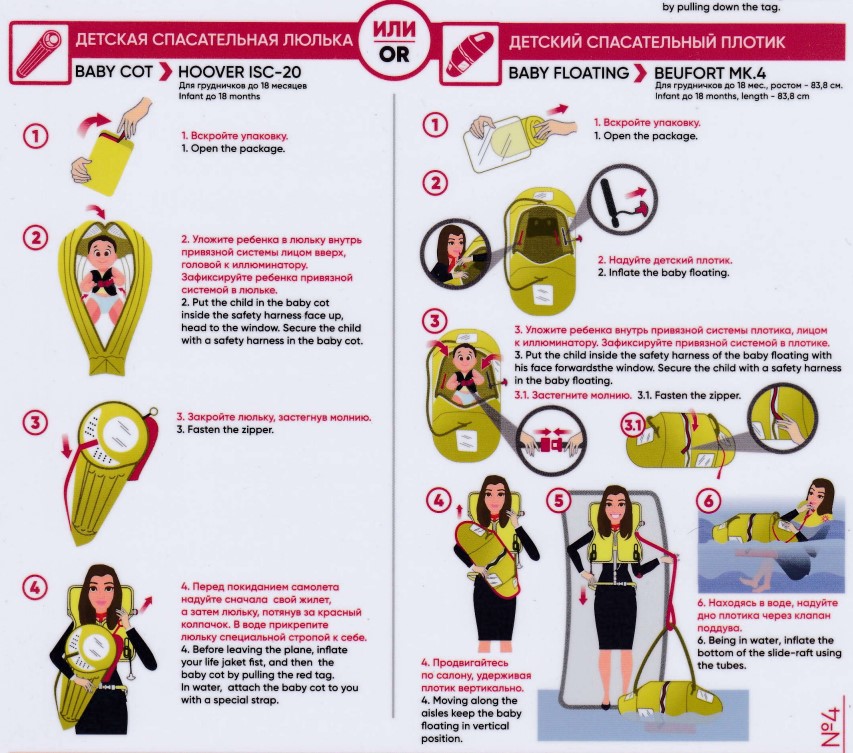

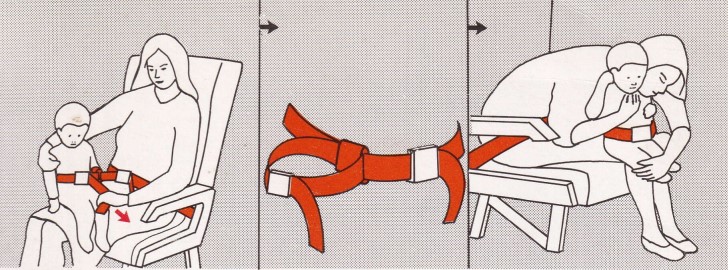

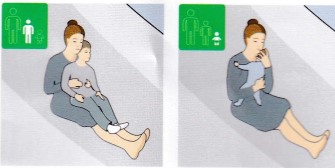

Another routine subject increasingly shown on safety cards is the restraint method for children and infants. Here, a difference exists between the U.S. and other continents (including Europe). The FAA prohibits the use of infant loop belts, while it is promoted in Europe. In either case, the better option is the use of a “child restraint device,” but this requires a separate seat, which not everyone is willing to buy.

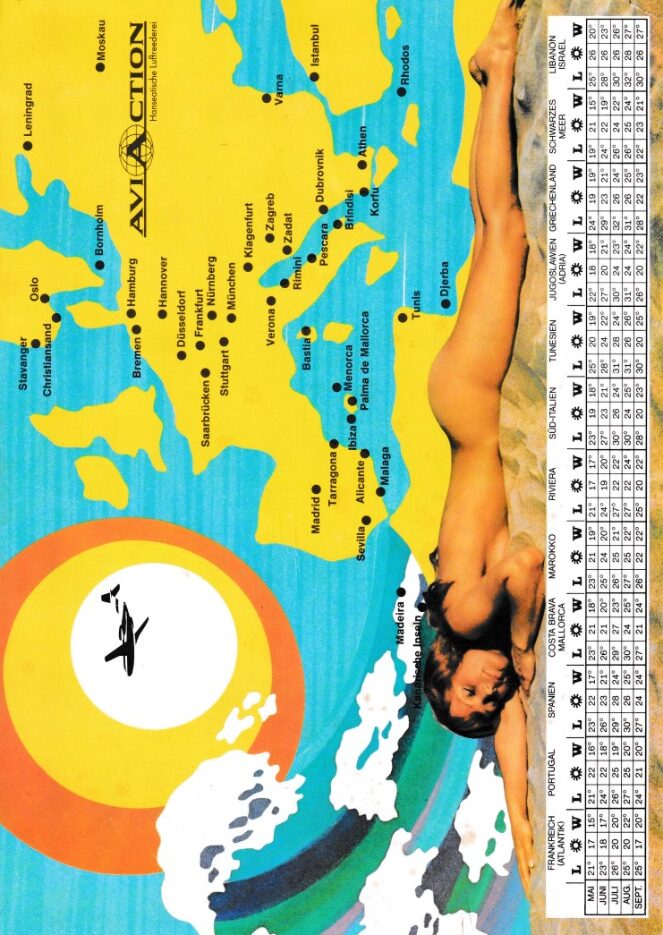

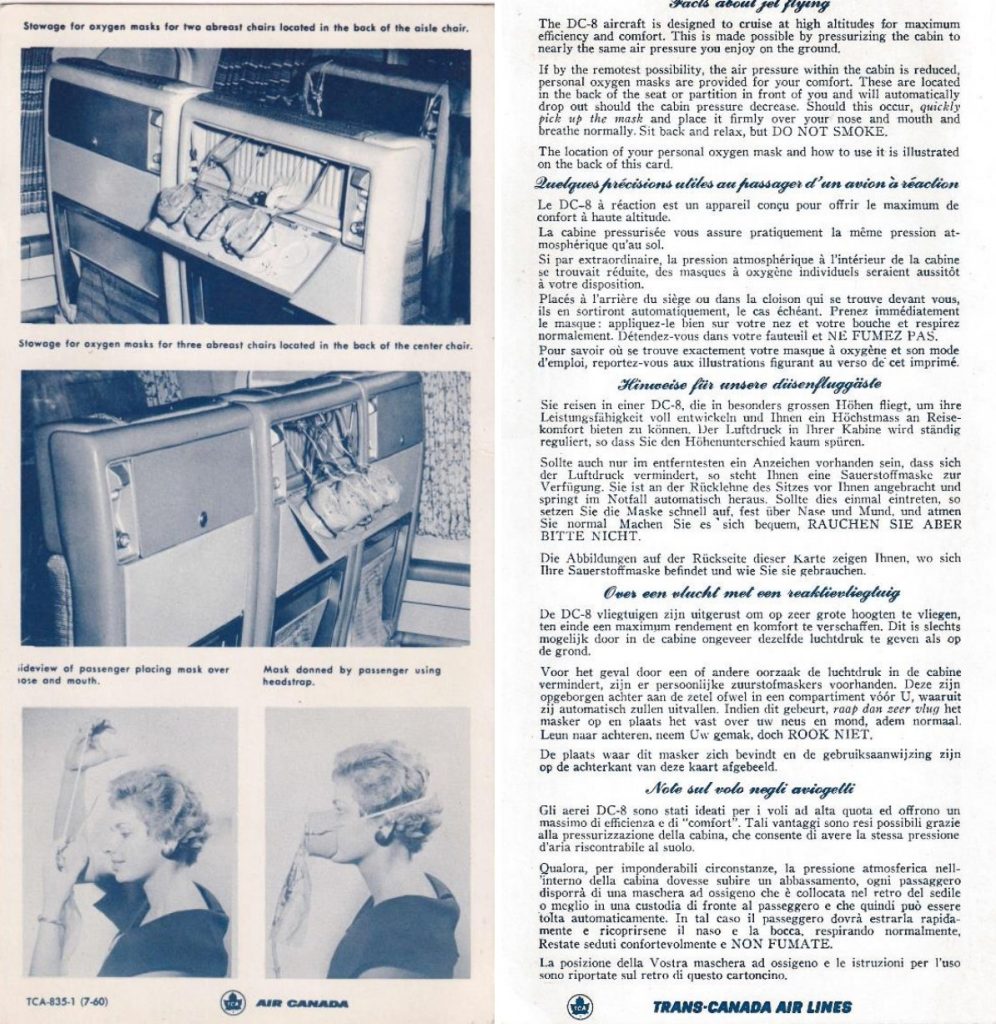

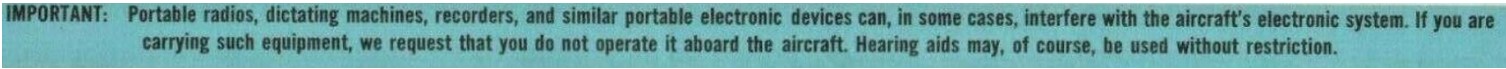

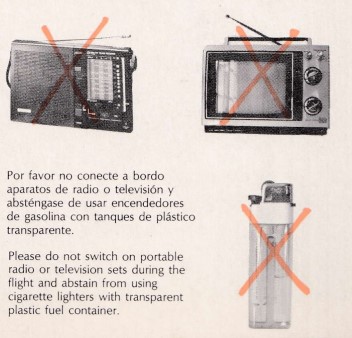

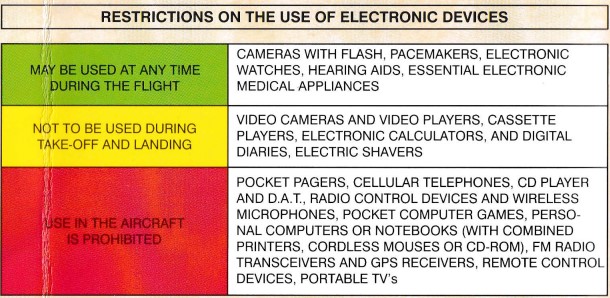

An area in which safety card contents changed significantly over the past few decades is transmitting devices. In the 1980s TVs and remotely-operated toys appeared as prohibited items on safety cards. More devices were prohibited in the 1990s and 2000s, such as illustrated on a 737-400 card from an unidentified Spanish operator (believed to be Air Europa, c. 2000).

Other companies listed them in text format only, such as Cubana.

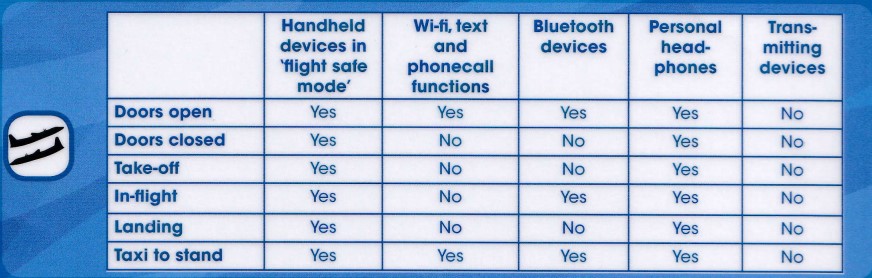

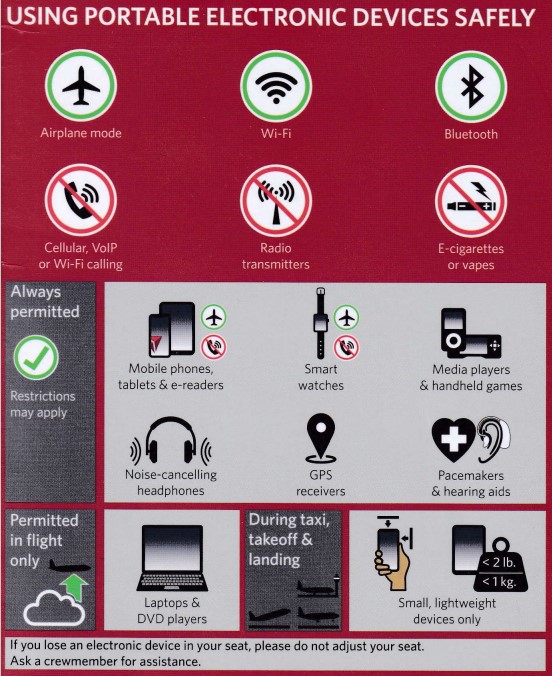

In those decades there was a specific concern about such devices as Nintendo games as they could affect the airplane’s navigation equipment. The prohibition was extended to mobile telephones when they appeared, and their successor, the smartphone. The mobile phone industry reacted and created the “airplane mode” option that switches off signal transmission. This allowed passengers to use them on board. From 2010 onwards, tablets have been popular. As they also have an “airplane mode” their use onboard was also allowed. The information displayed on safety cards for electronic devices varies from virtually nil to extensive lists of what is allowed. Typically, this is split into taxi/take-off/landing phases and the cruise phase but VLM in 2017 recognized six distinct flight phases.

Emergency Subjects

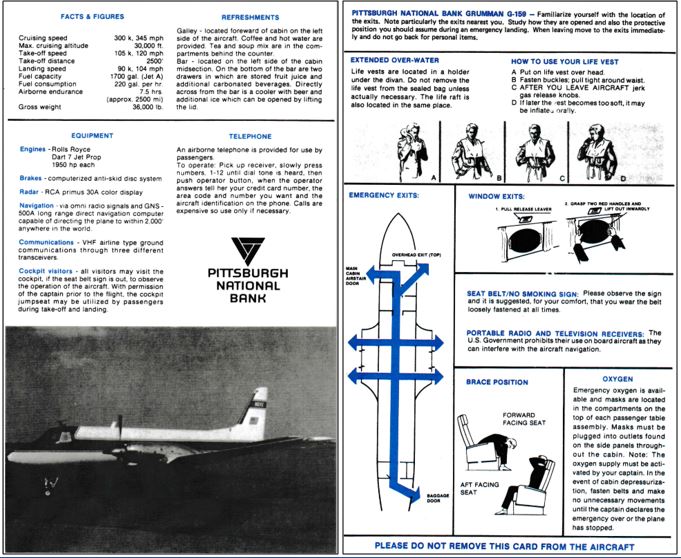

Emergency subjects on safety cards address four scenarios: (1) the in-flight decompression, (2) the crash landing, (3) escape on the ground and (4) escape and survival on water. Additionally, some cards include other emergency equipment.

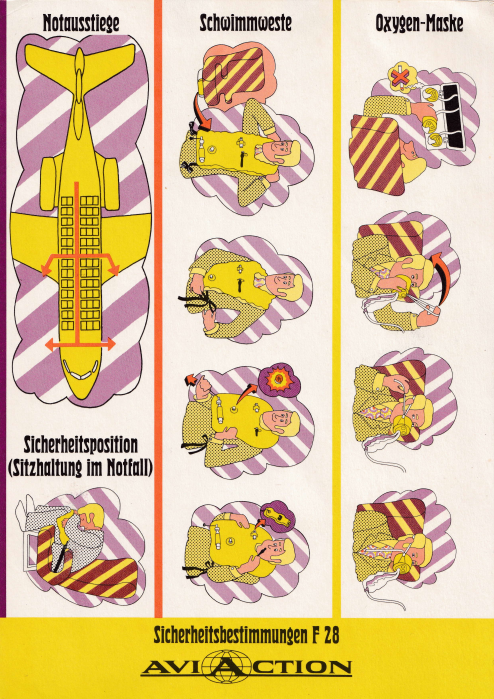

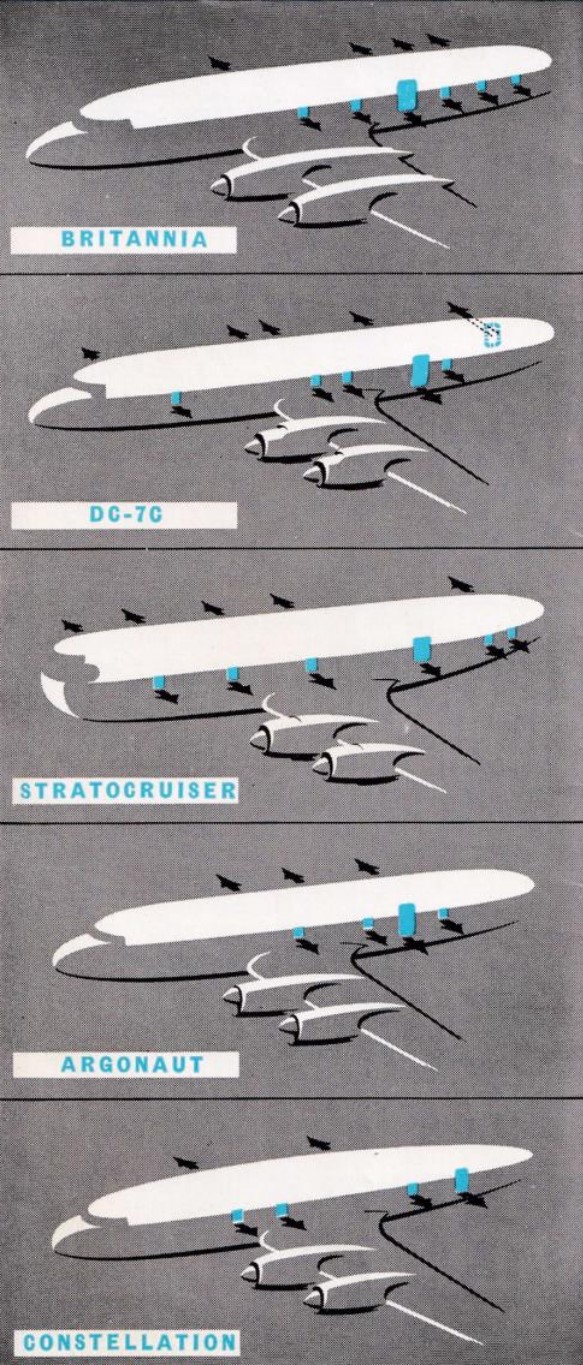

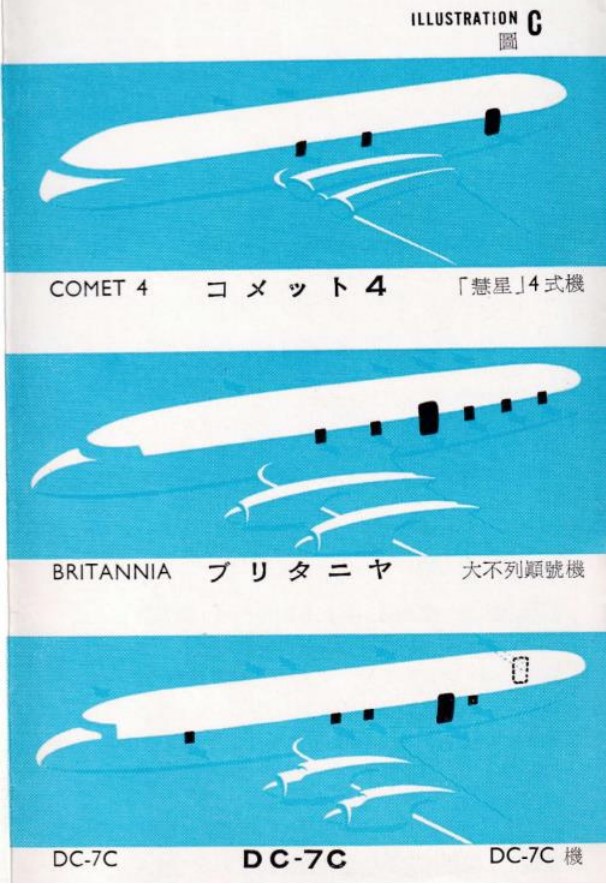

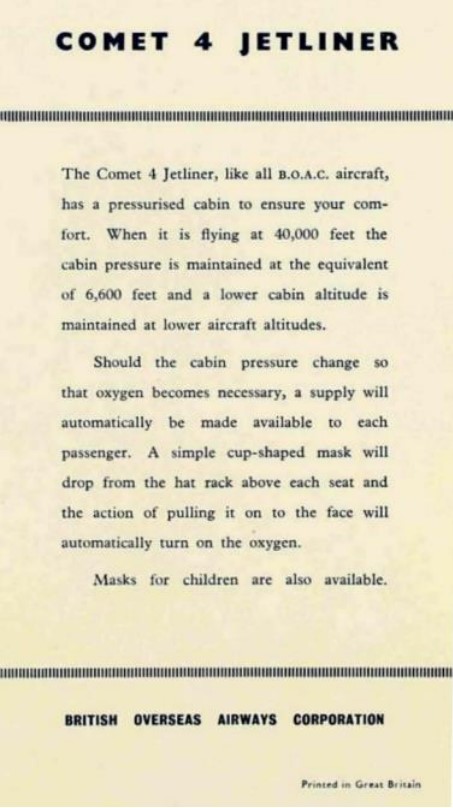

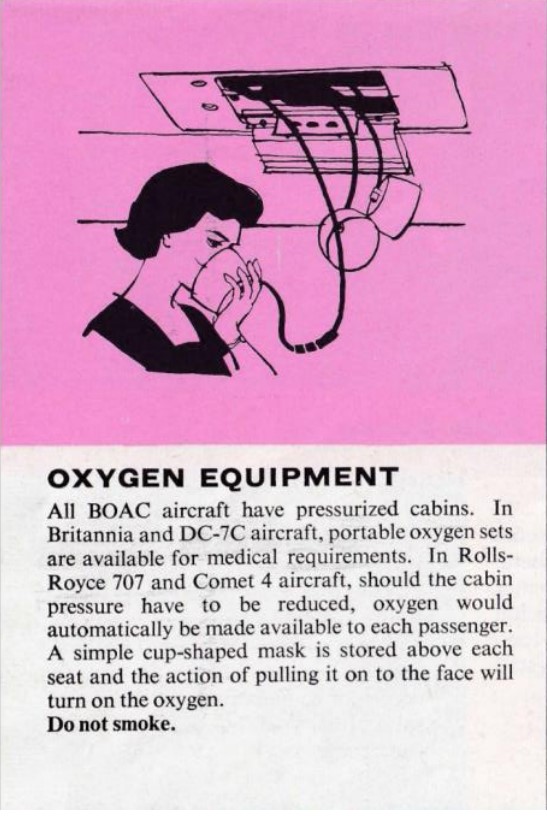

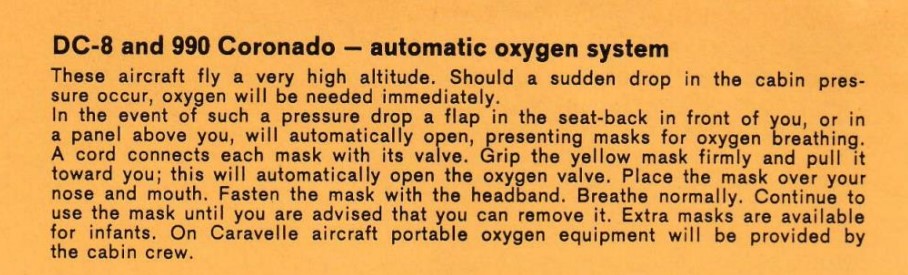

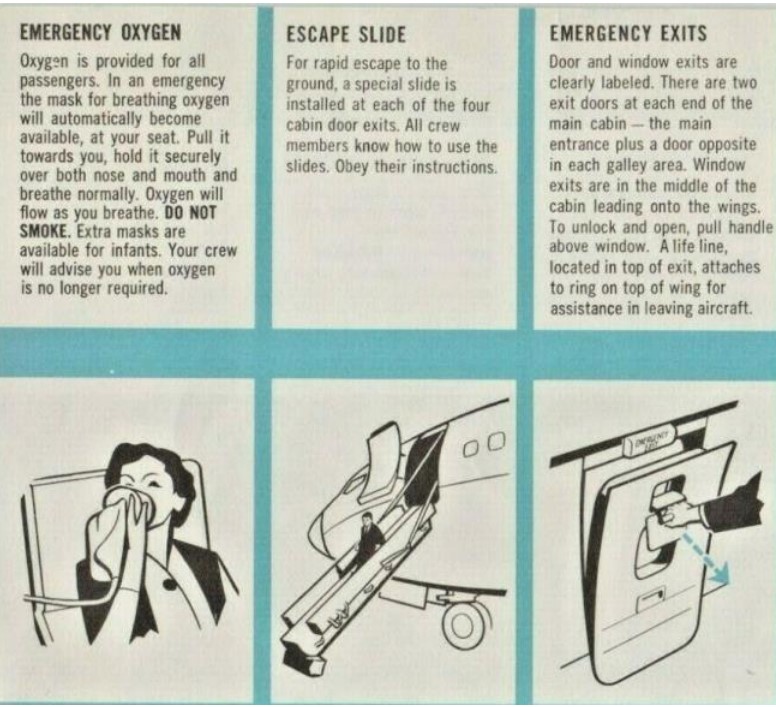

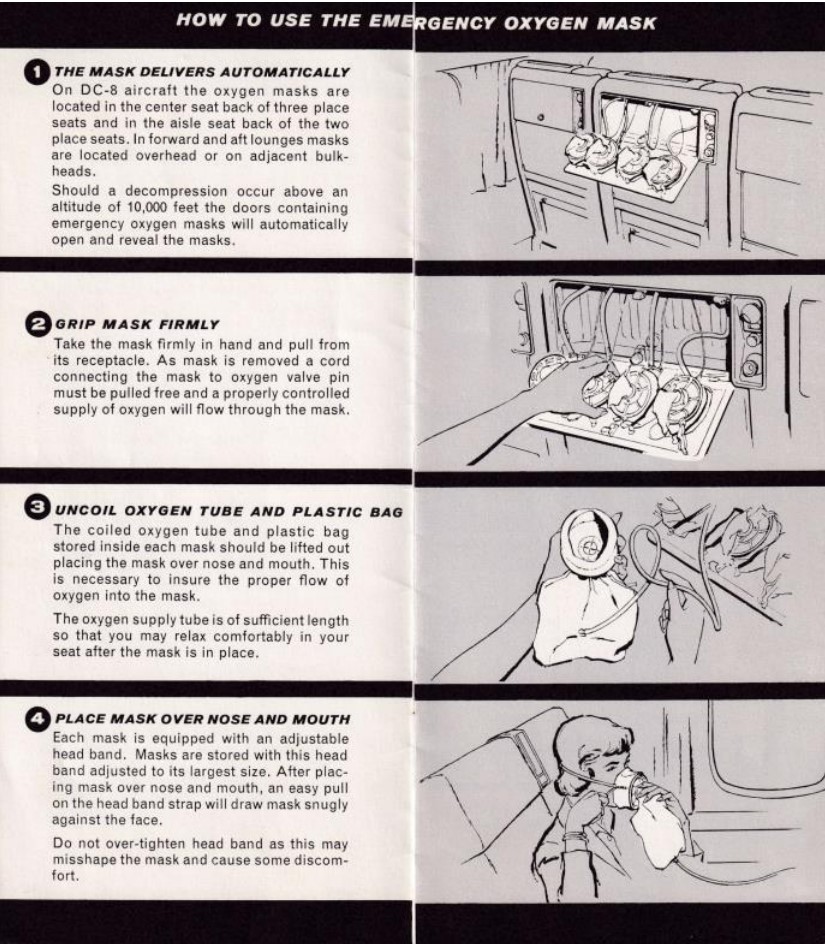

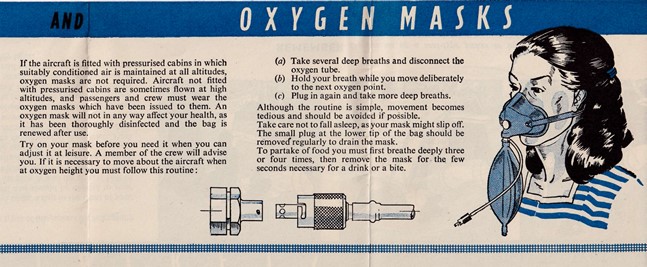

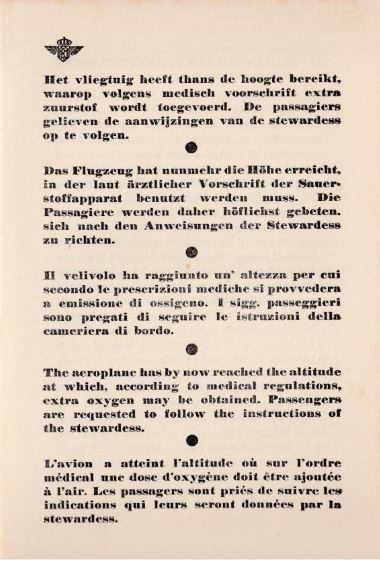

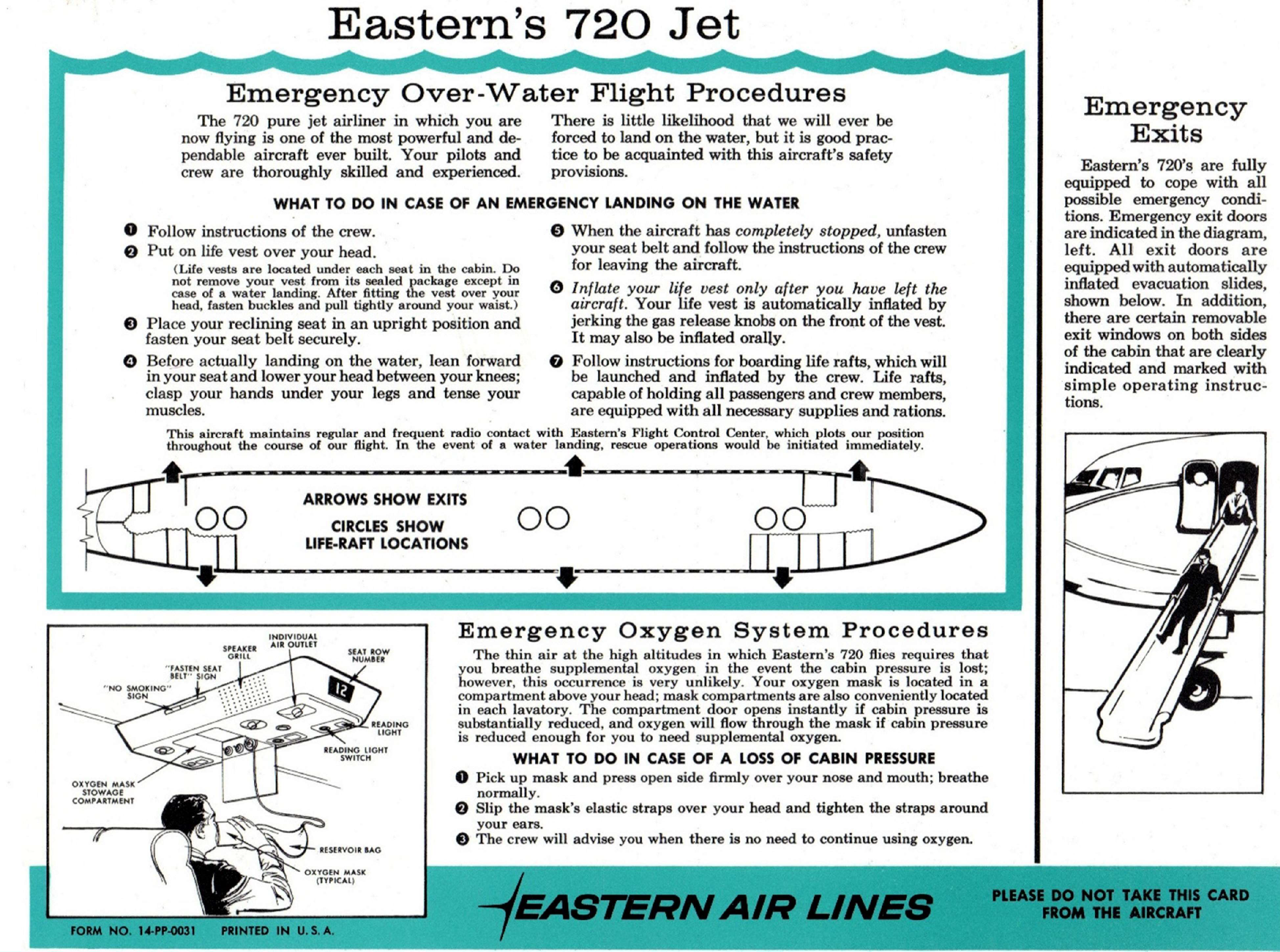

Oxygen

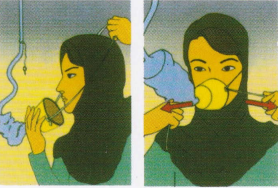

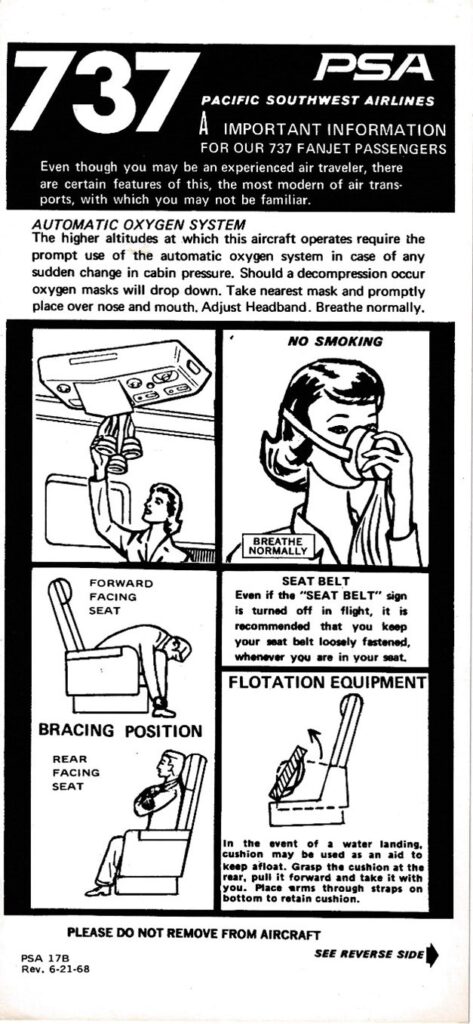

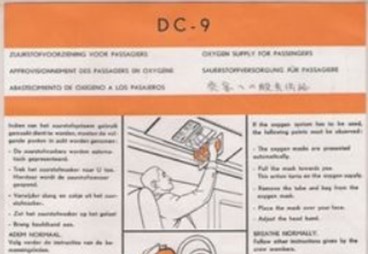

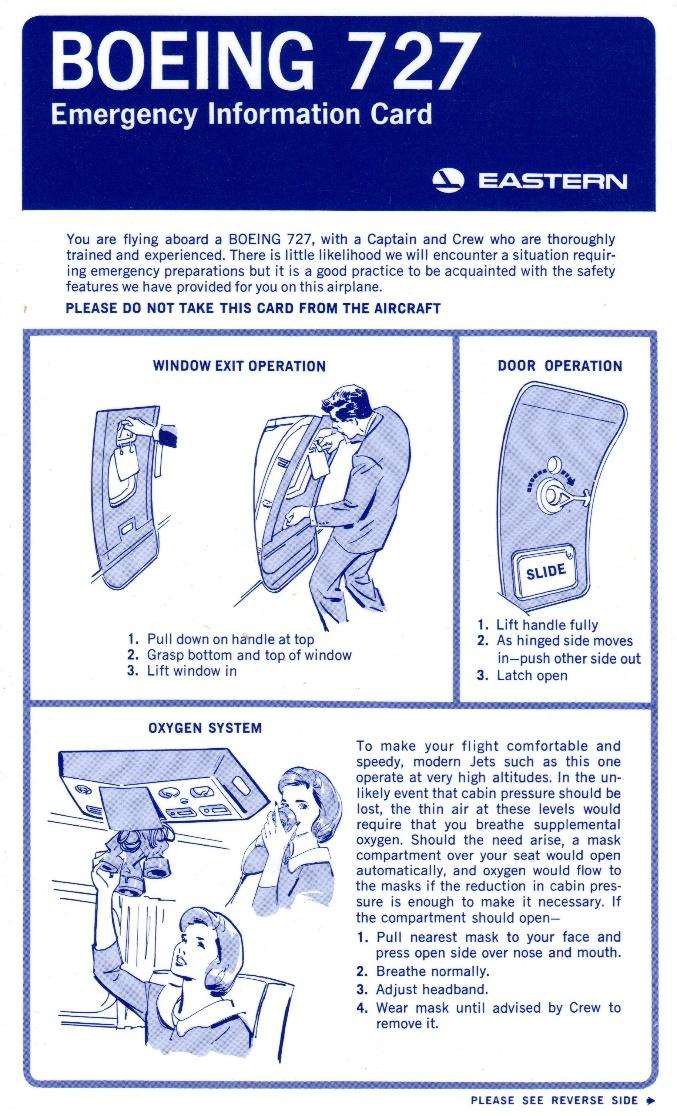

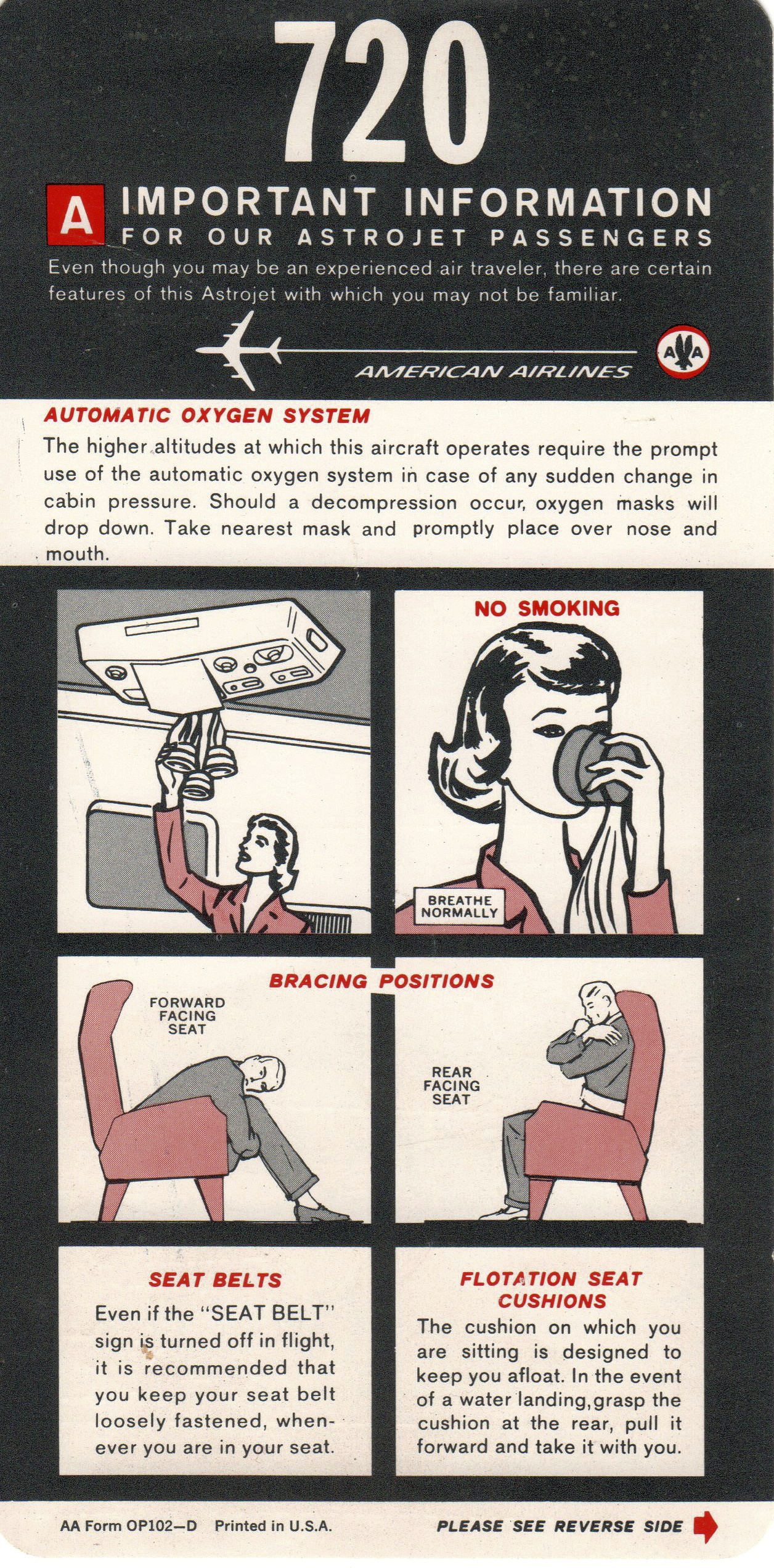

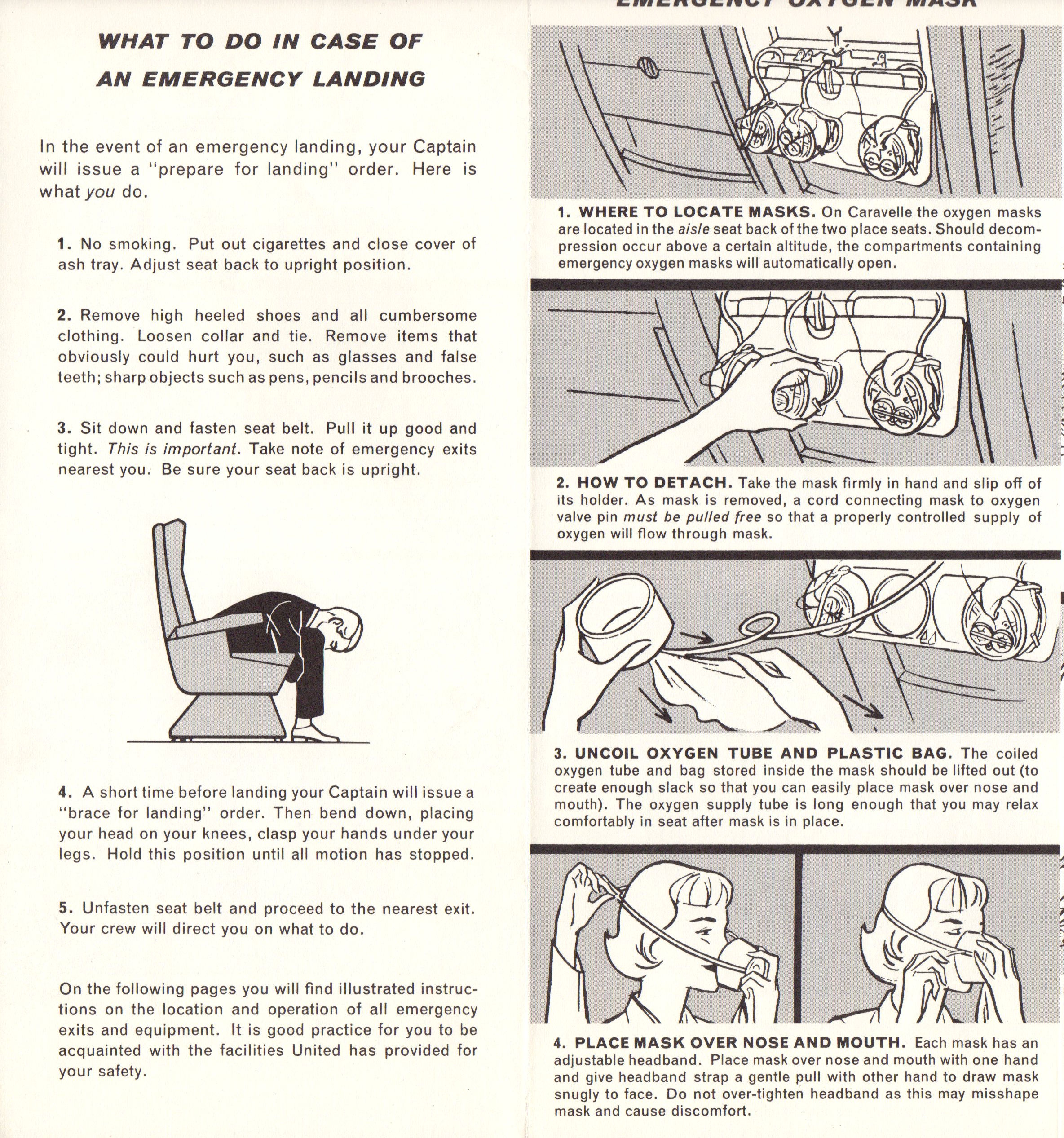

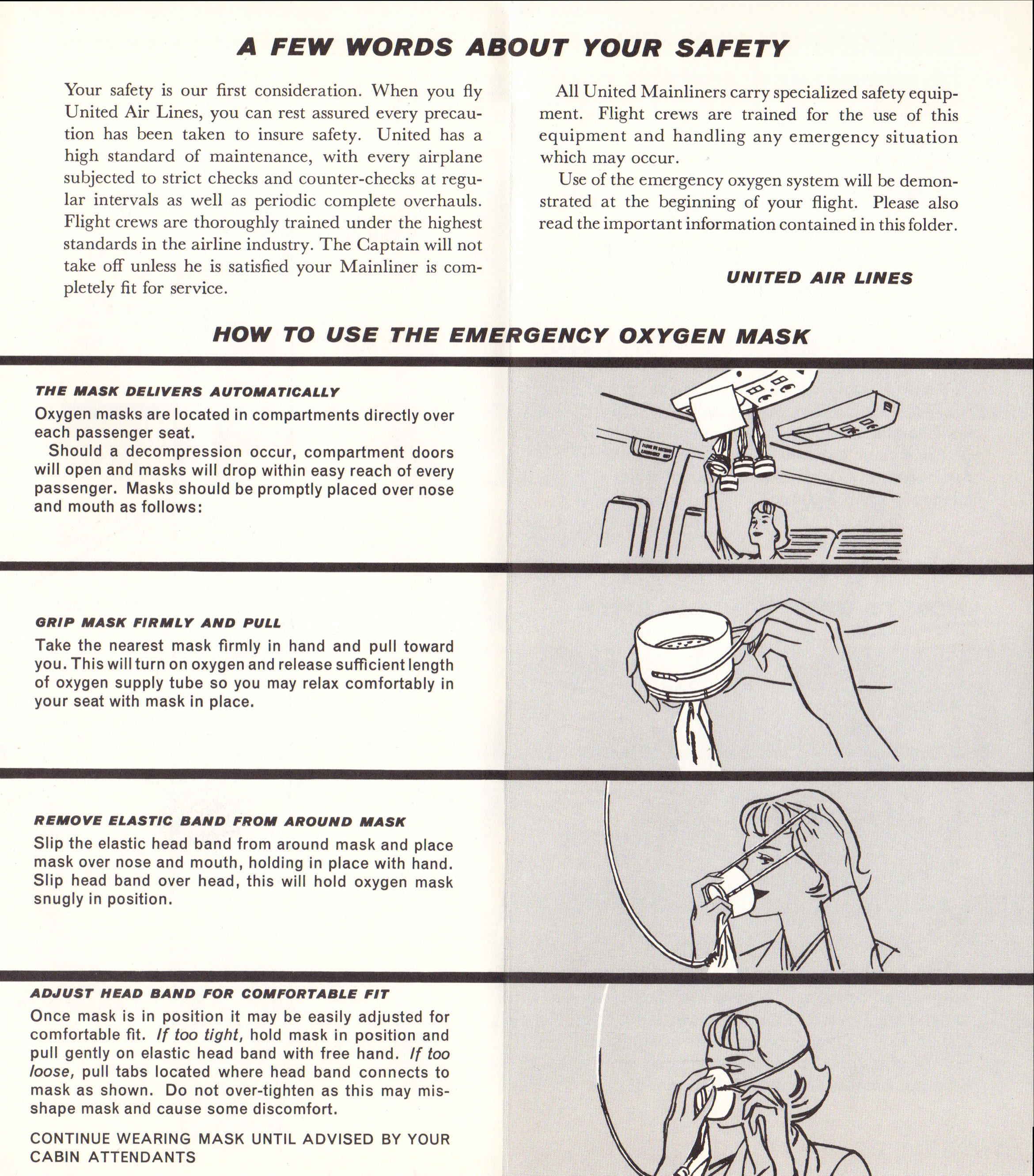

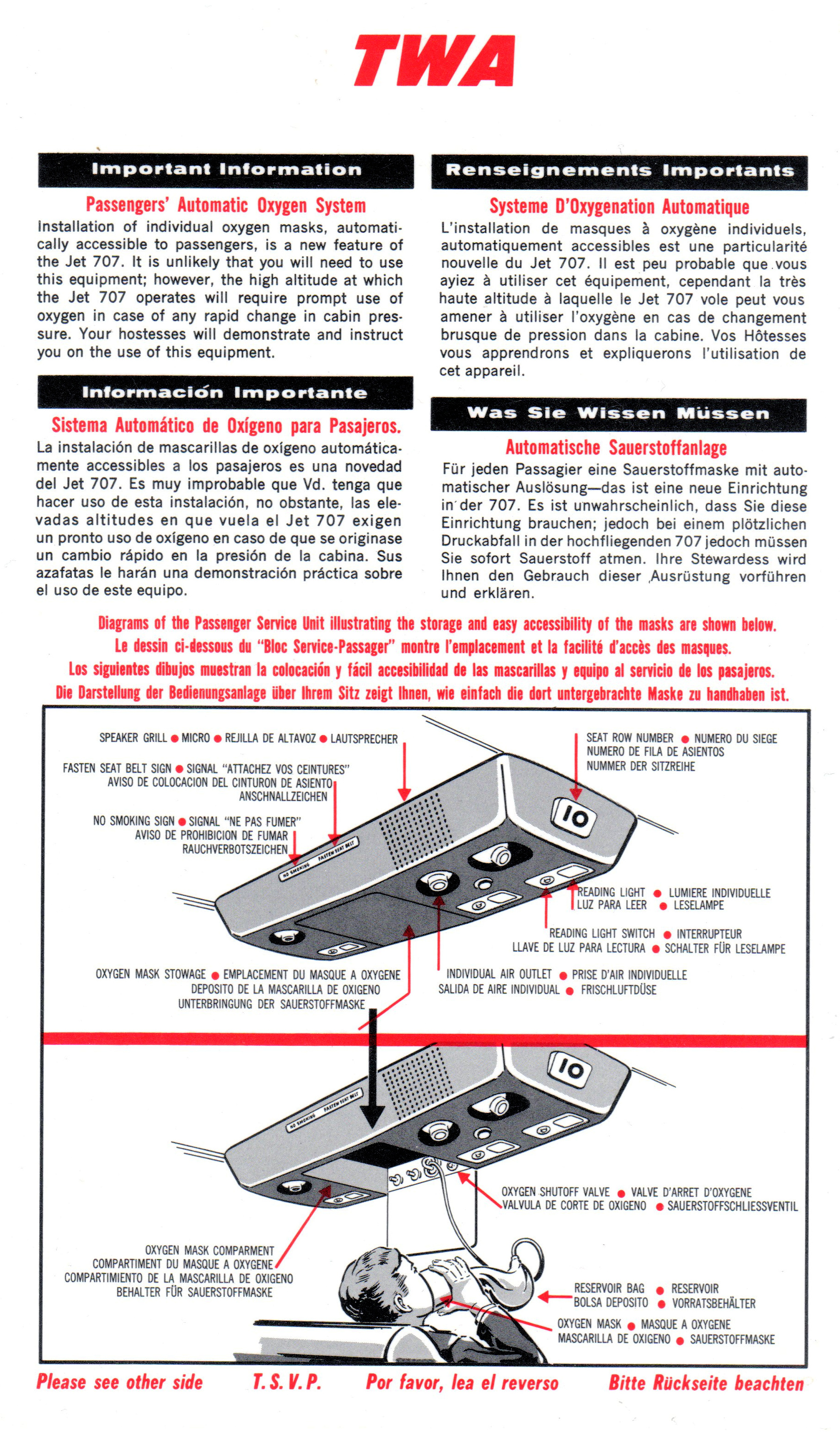

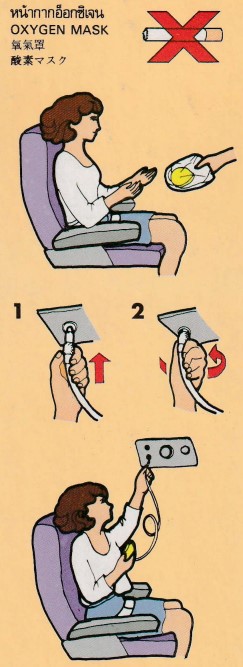

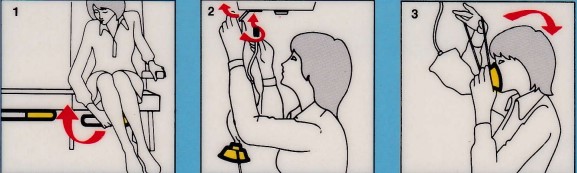

For the in-flight decompression emergency, the main concern is the provision of oxygen. Most airplanes have a system that deploys automatically. The card shows how to grab and don the mask, often with an extra panel showing an adult administering a mask to a child, but only after first securing their own mask. Some airlines add a clock to these diagrams explaining the time needed for each step. Typically, the final step – an adult donning the mask of a child – should be concluded within 10 to 15 seconds.

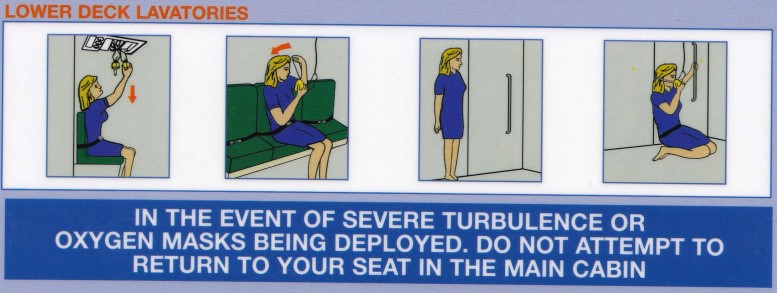

Oxygen masks should be available wherever passengers may be during the flight. Some cards specifically show oxygen masks in lavatories. An airline that grouped the lavatories on the lower deck (below the main cabin) added a page with safety instructions specific to that deck, including the use of oxygen masks in the waiting area.

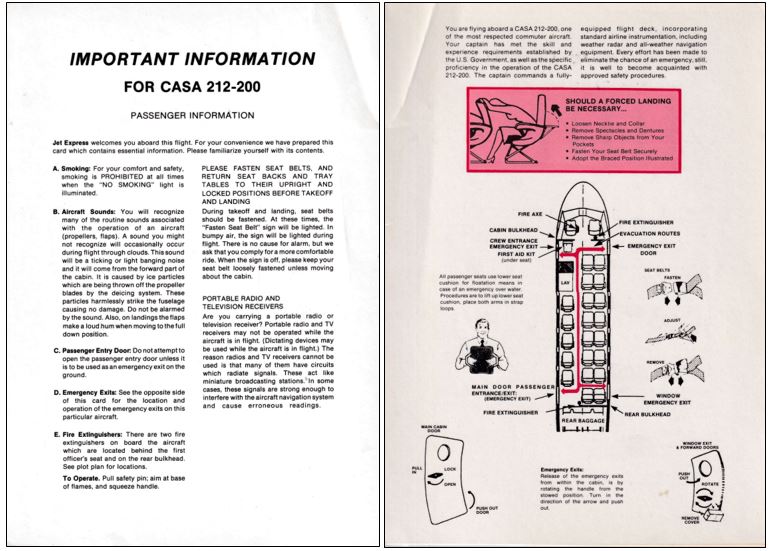

Airplanes with limited ceilings, typically turboprops, may have a non-drop-out system. Passengers need to plug a mask into an overhead outlet connected to a piping system. The masks are either handed out or need to be retrieved from under the seat.

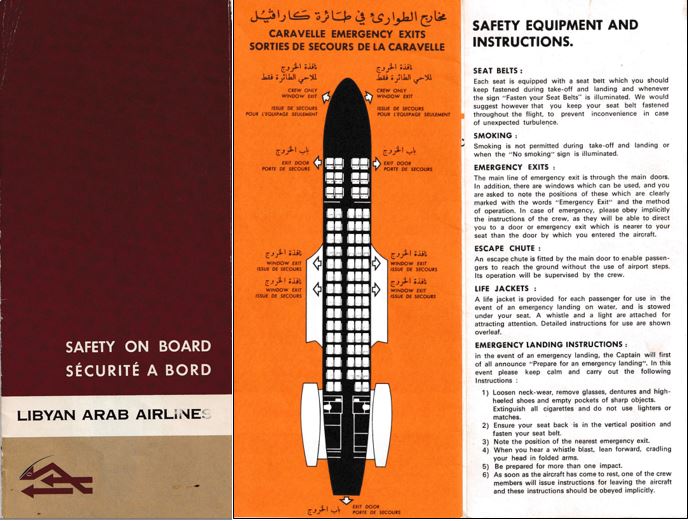

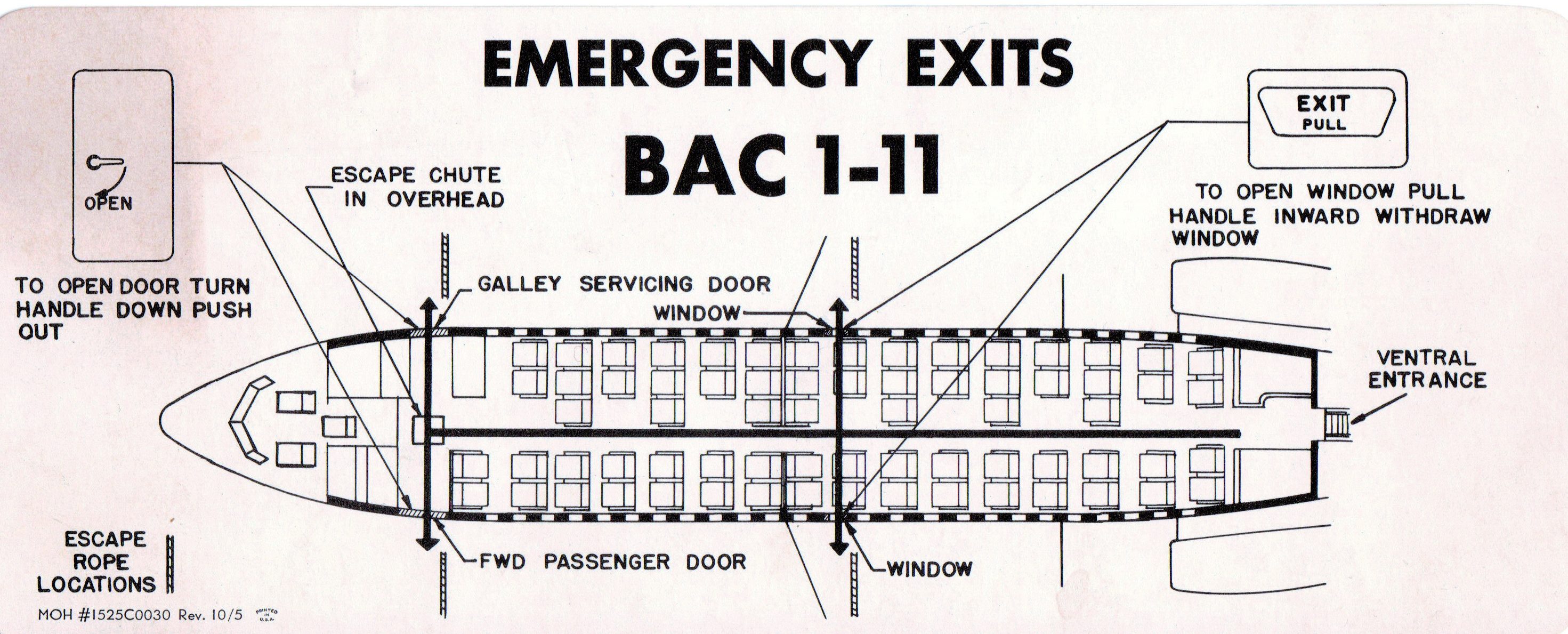

Yet, other airplanes do not even have that and their cards therefore lack any oxygen instructions. Next to airplanes that stay low, this also applied to some early European jets such as the BAC 1-11 and the Caravelle, in spite of their ceilings of up to 35,000 ft. Even though these airplanes suffered decompressions, the absence of oxygen did not lead to fatalities.

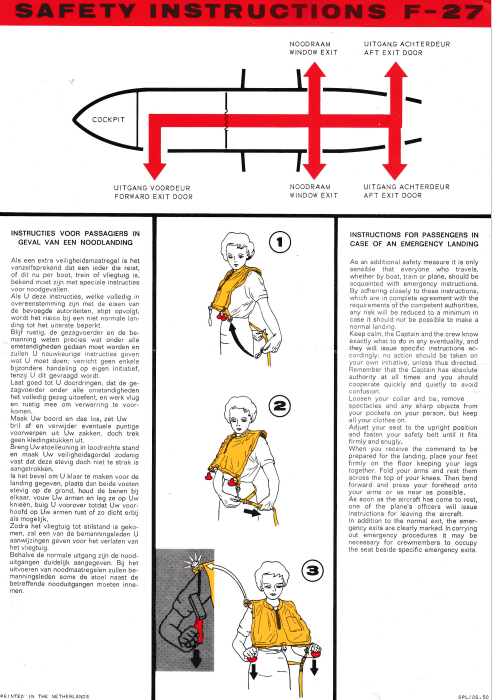

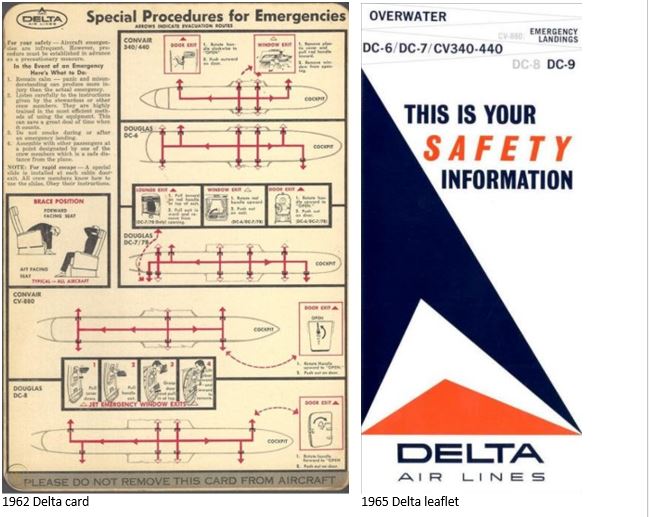

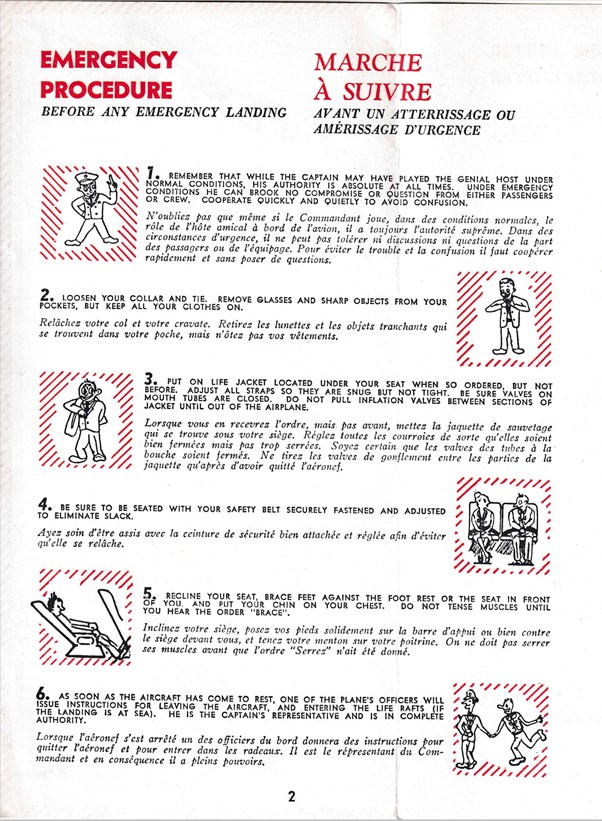

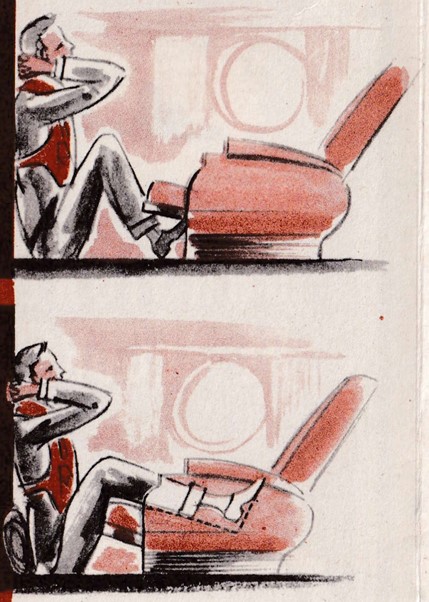

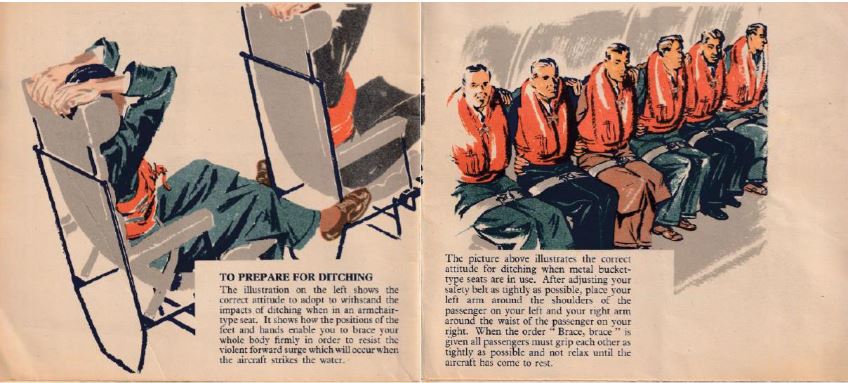

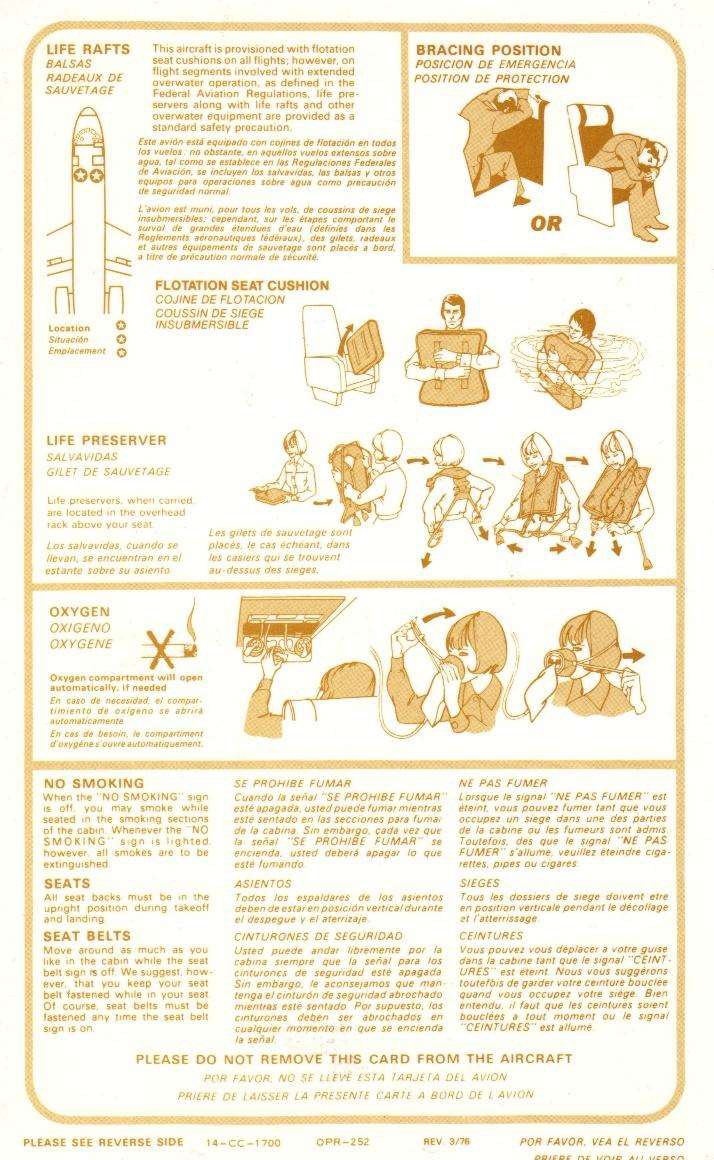

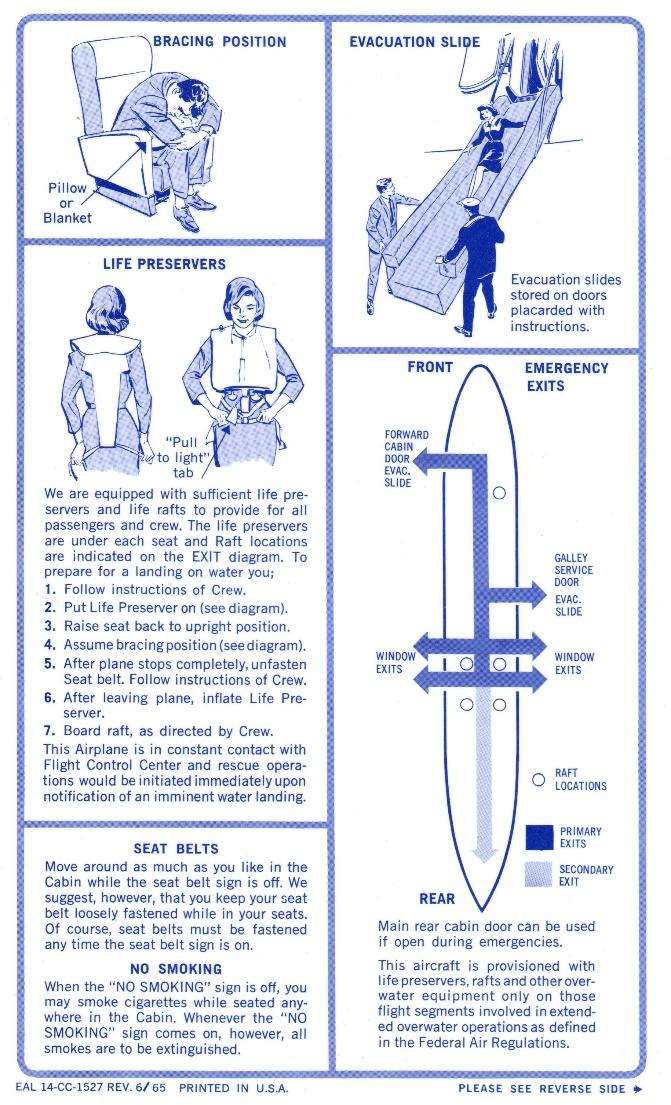

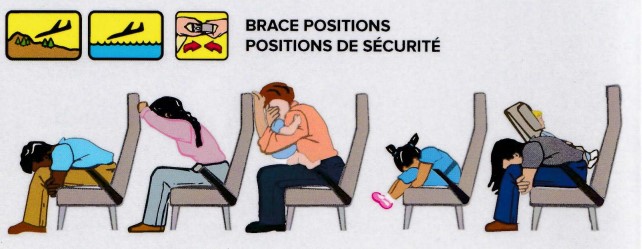

Brace For Impact

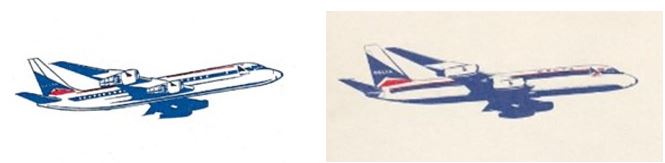

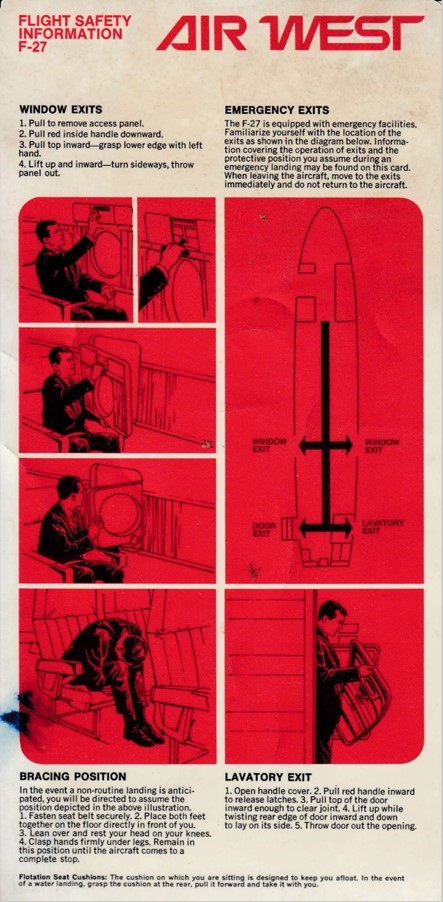

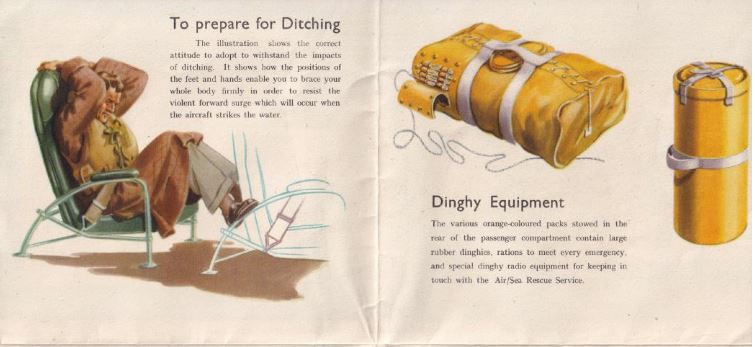

The main instruction associated with a crash landing is the “brace for impact” position. Airlines use a range of different positions. This not only varies for the type of person (adult, child, adult with infant, pregnant woman) but also the method of bracing varies. While most agree the body should be flexed forward, instructions on how to hold arms, hands, and feet differ. These reflect the results from various research studies into this area and the absence of internationally agreed standards. This concerns forward-facing seats; for aft-facing seats, there is more consistency.

Evacuation on Land

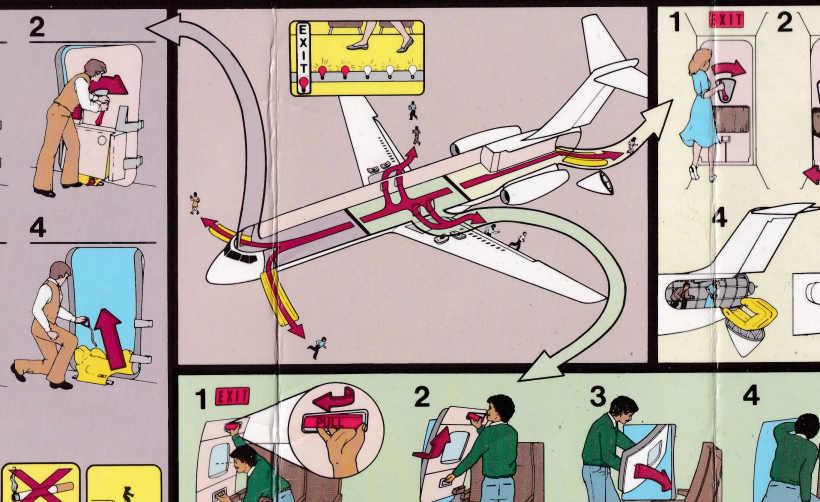

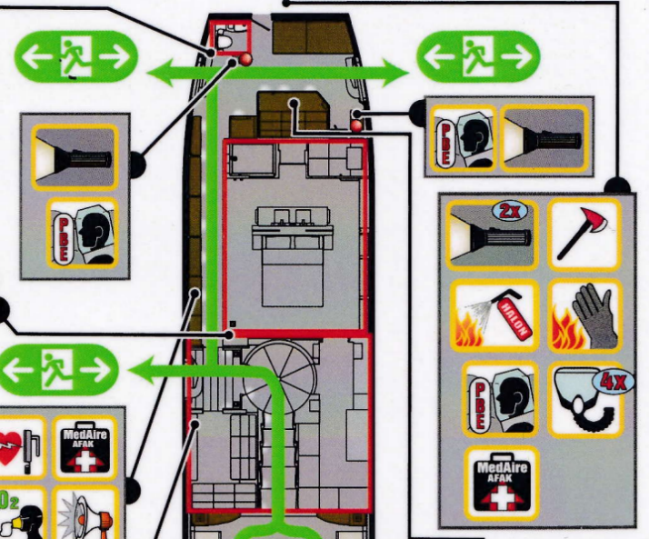

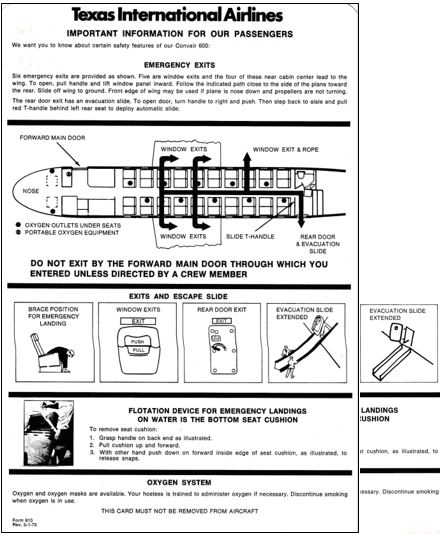

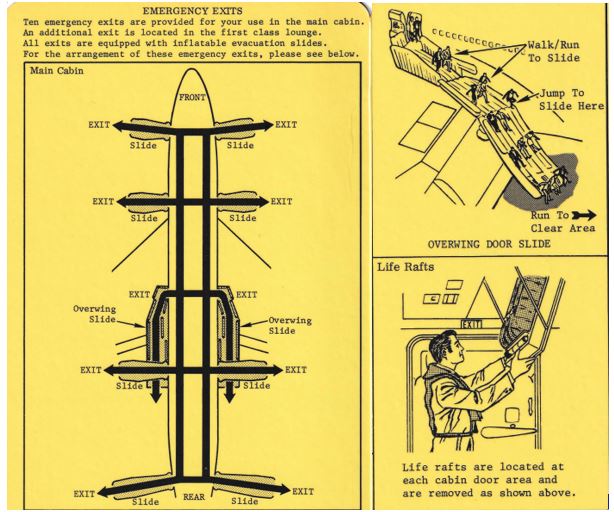

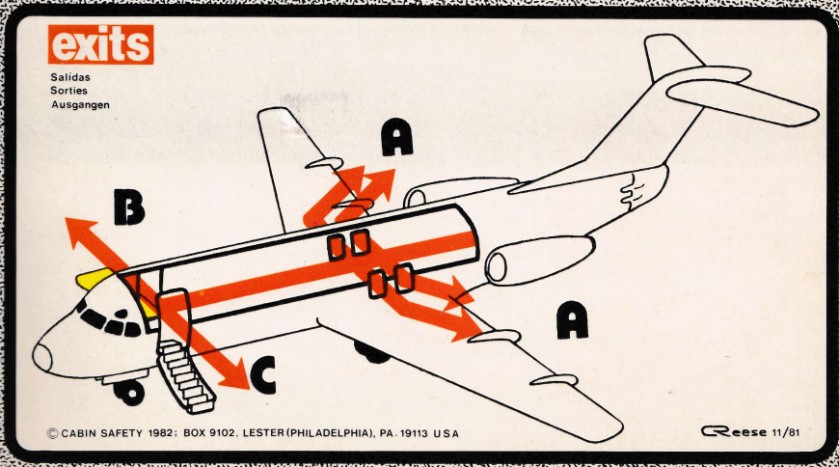

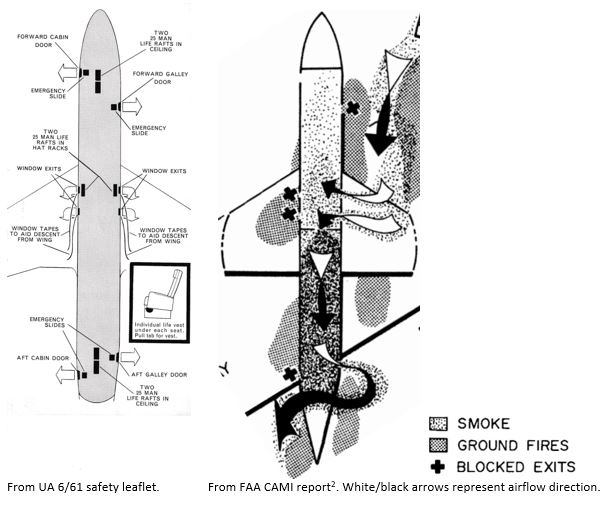

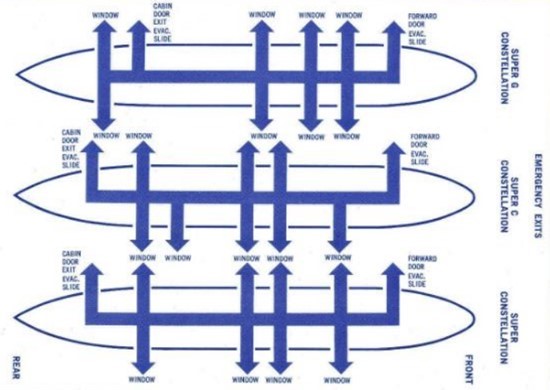

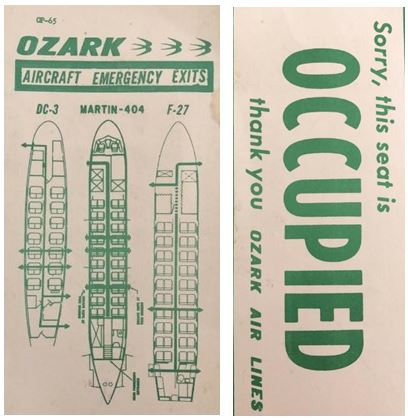

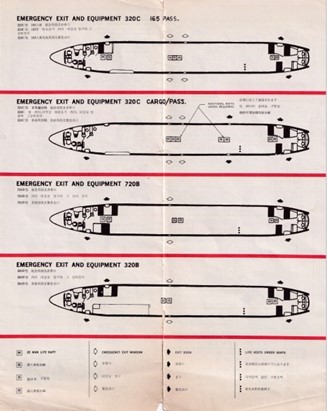

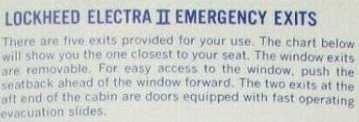

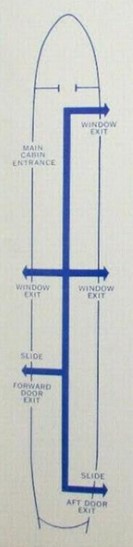

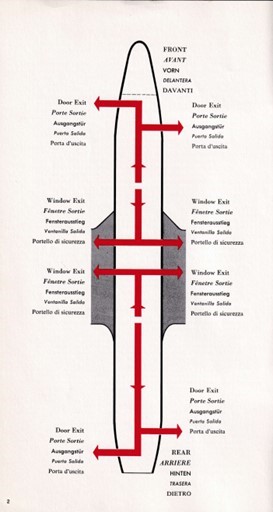

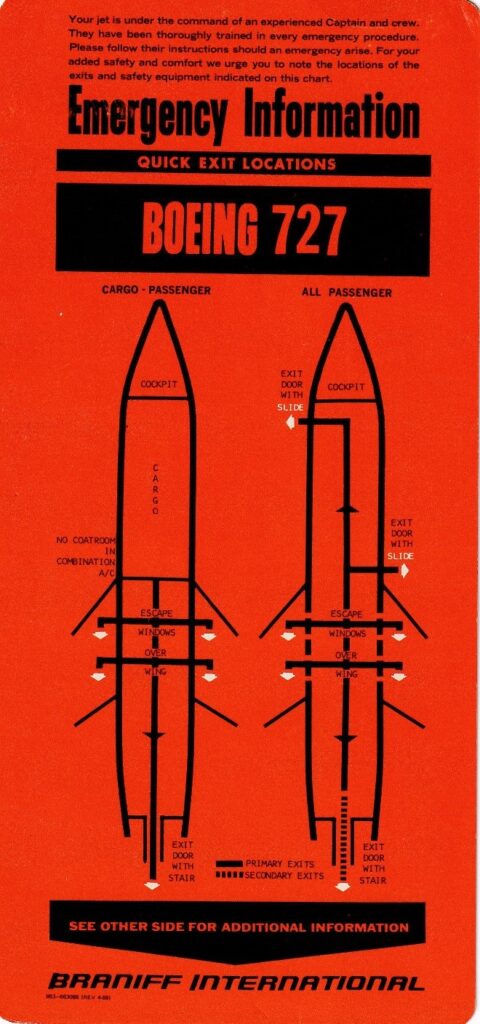

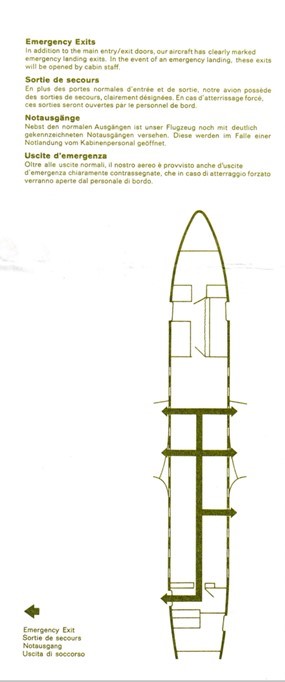

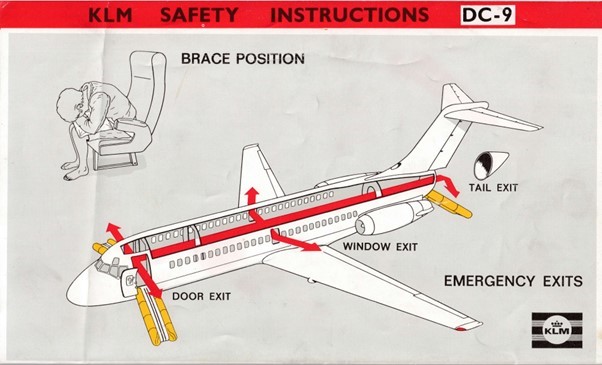

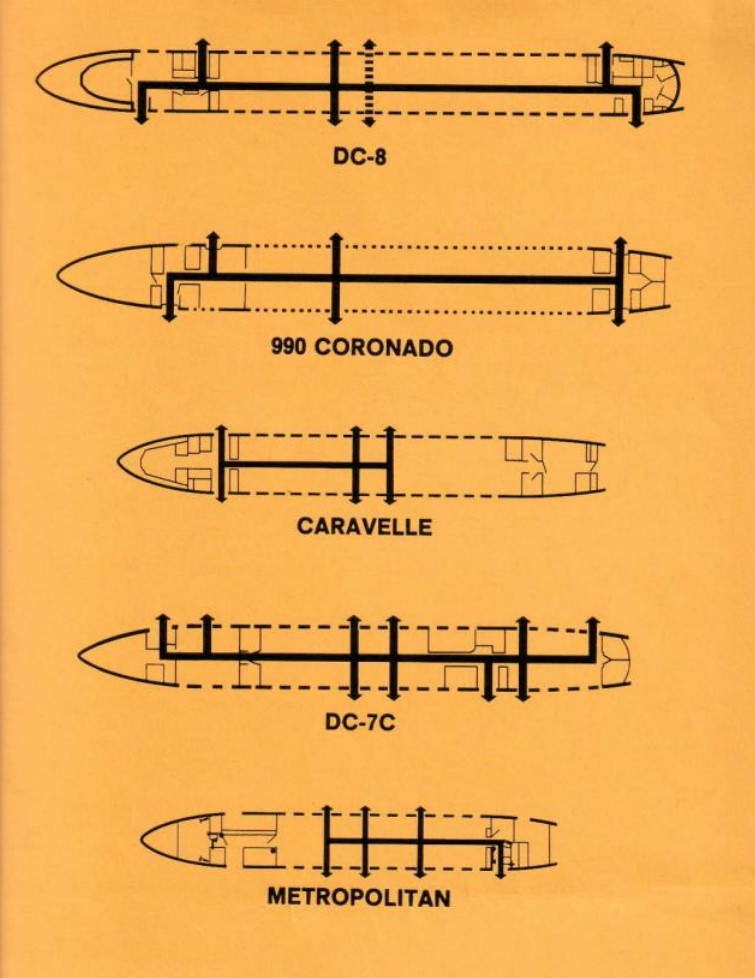

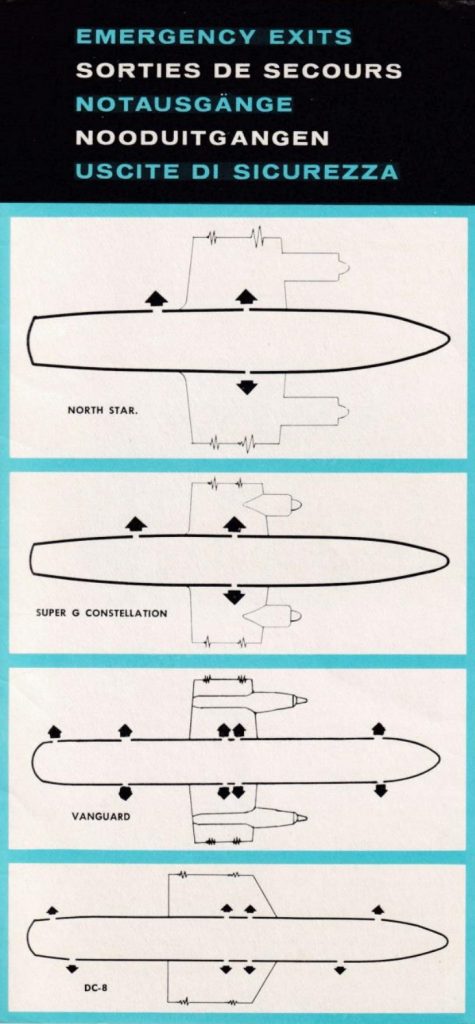

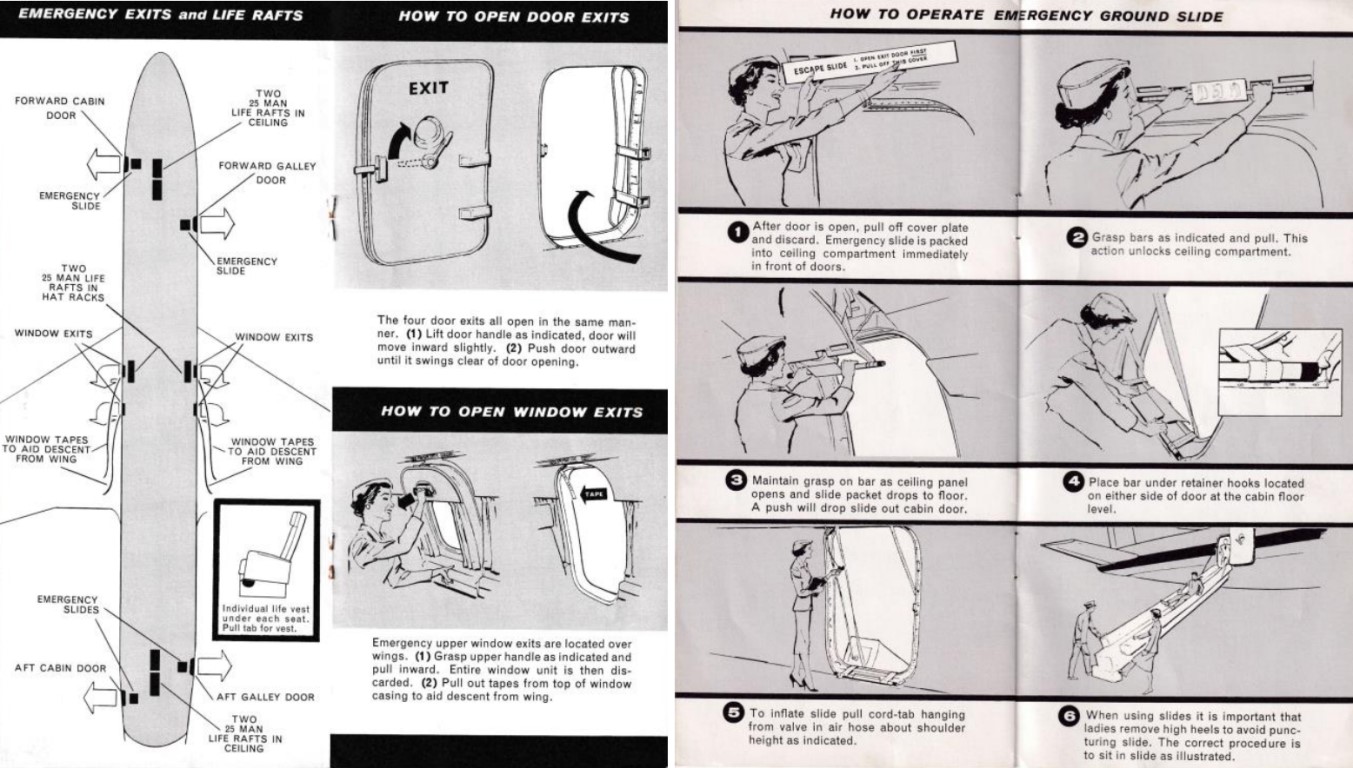

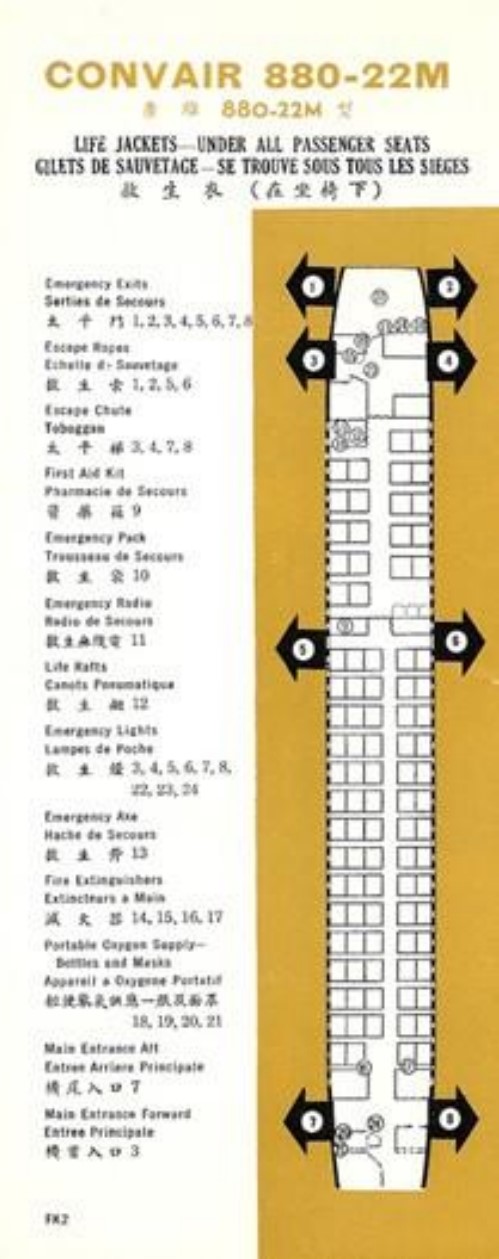

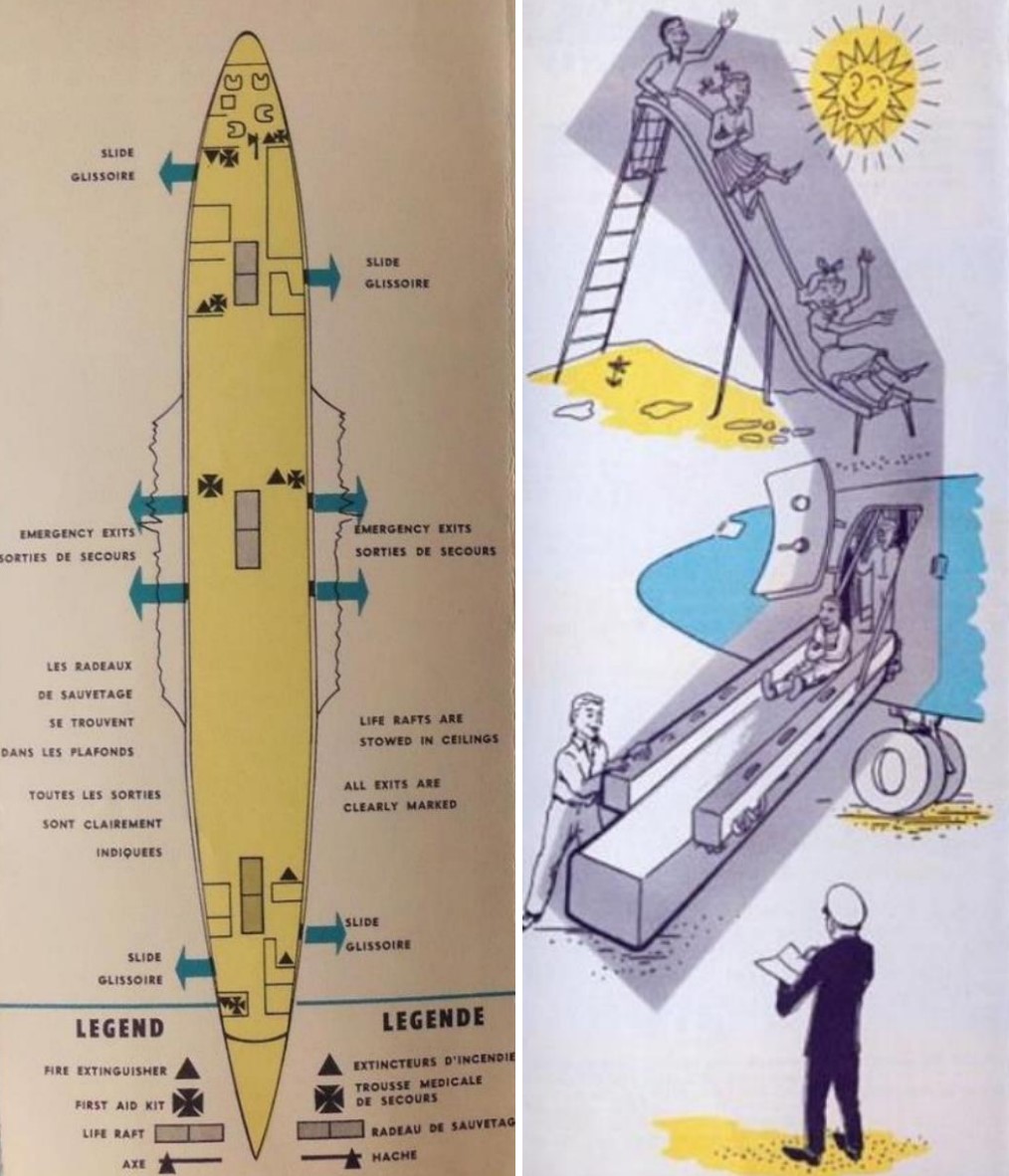

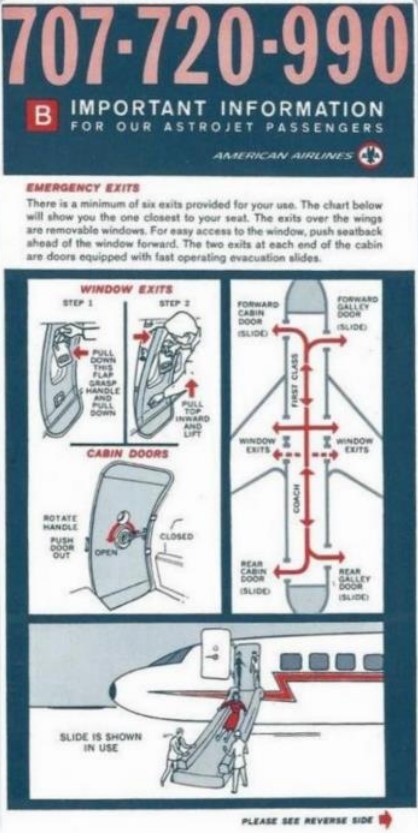

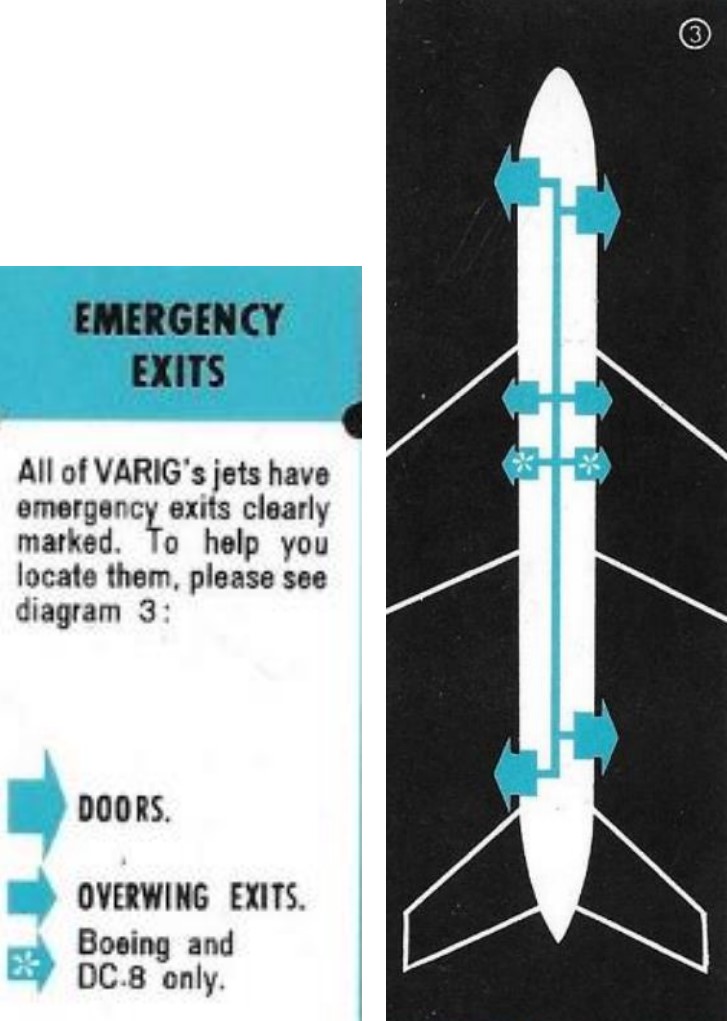

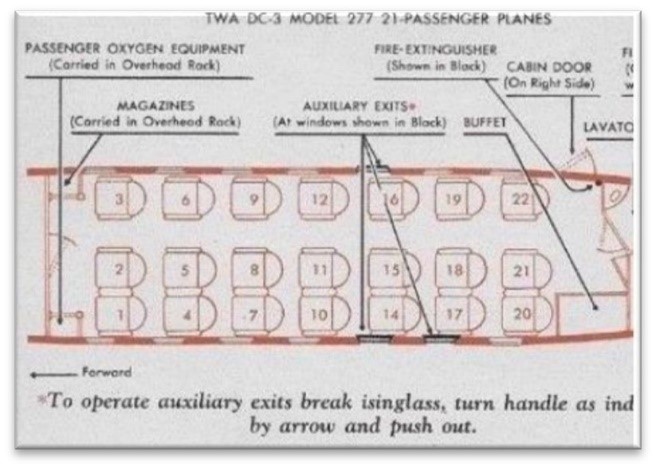

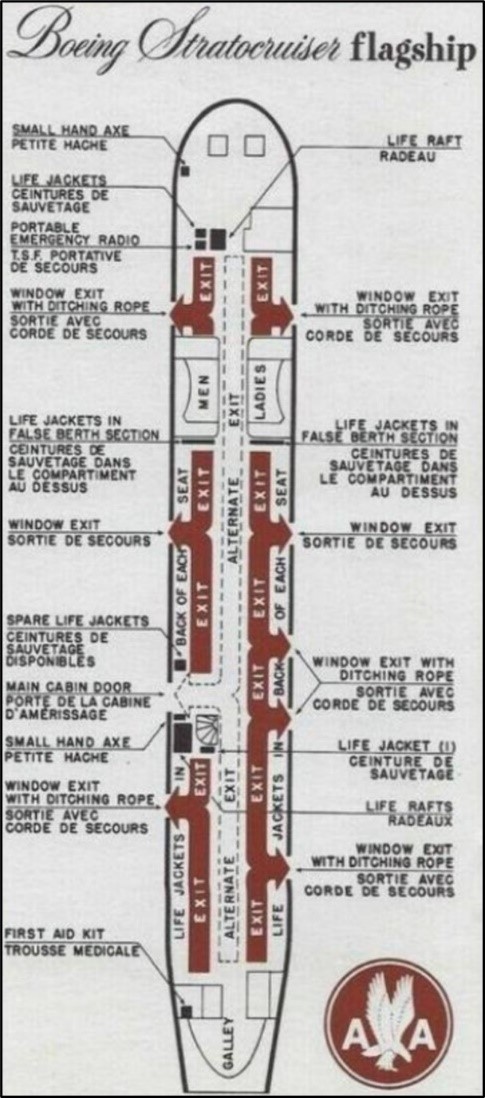

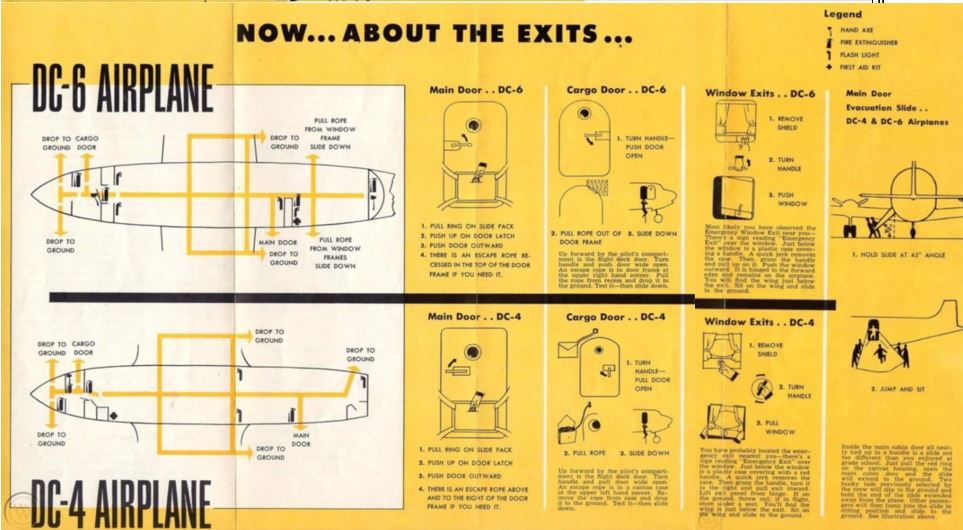

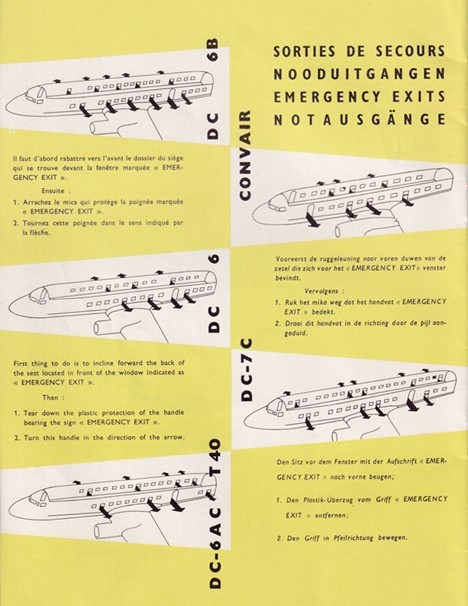

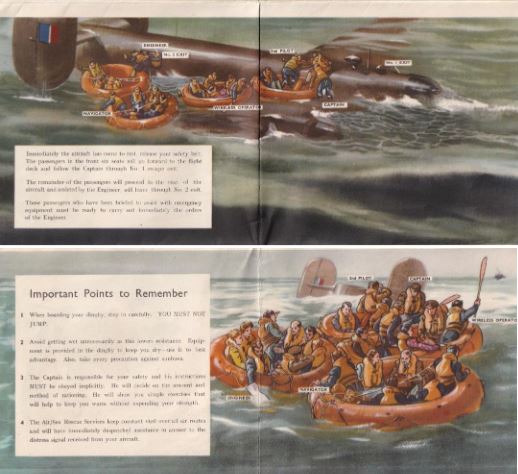

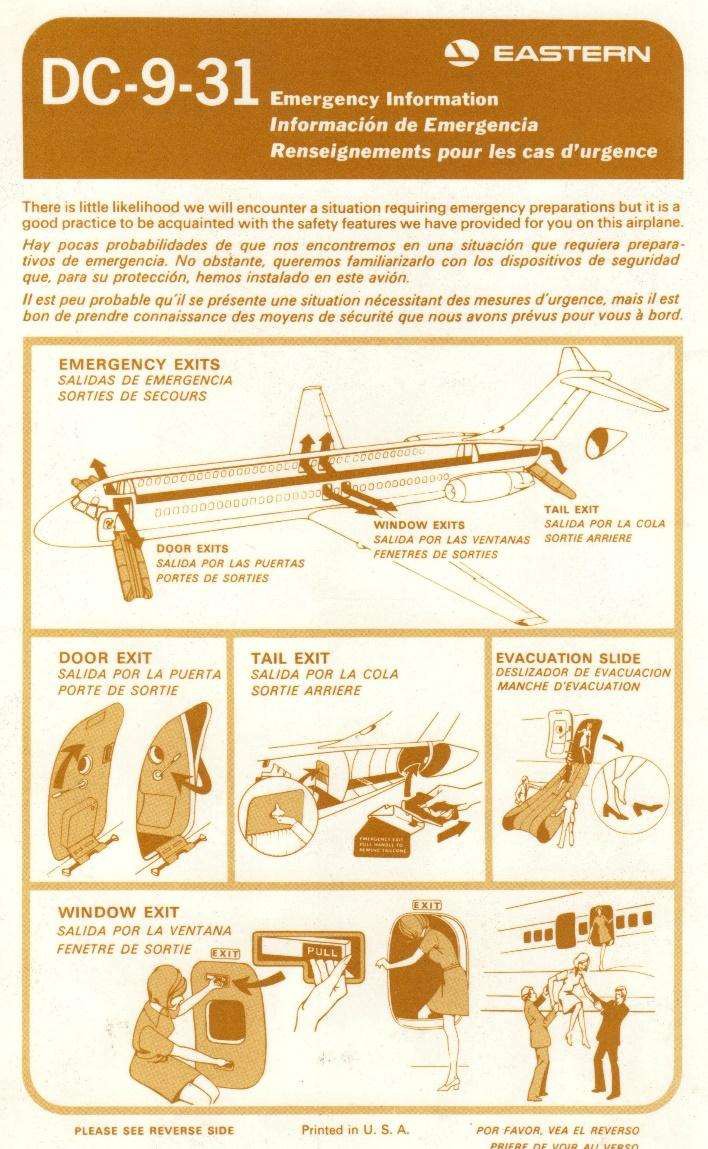

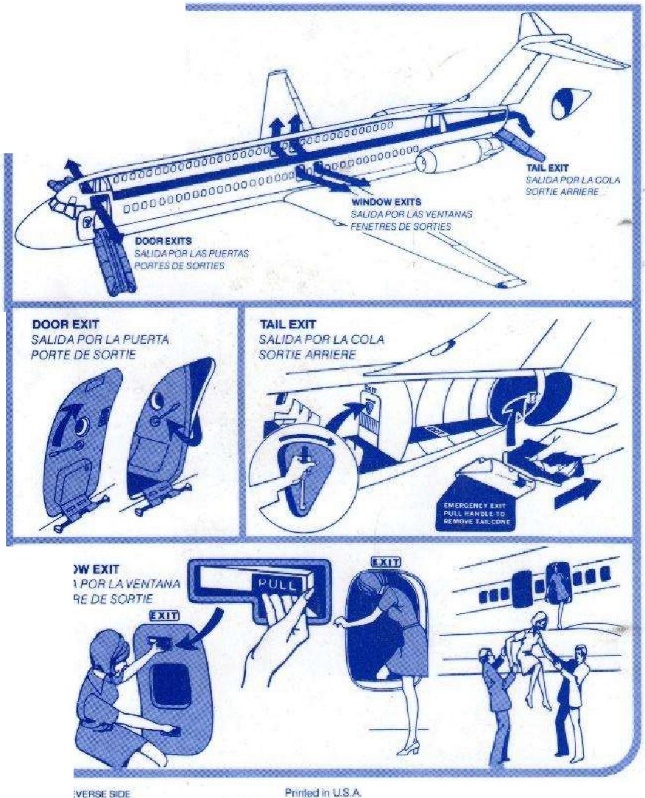

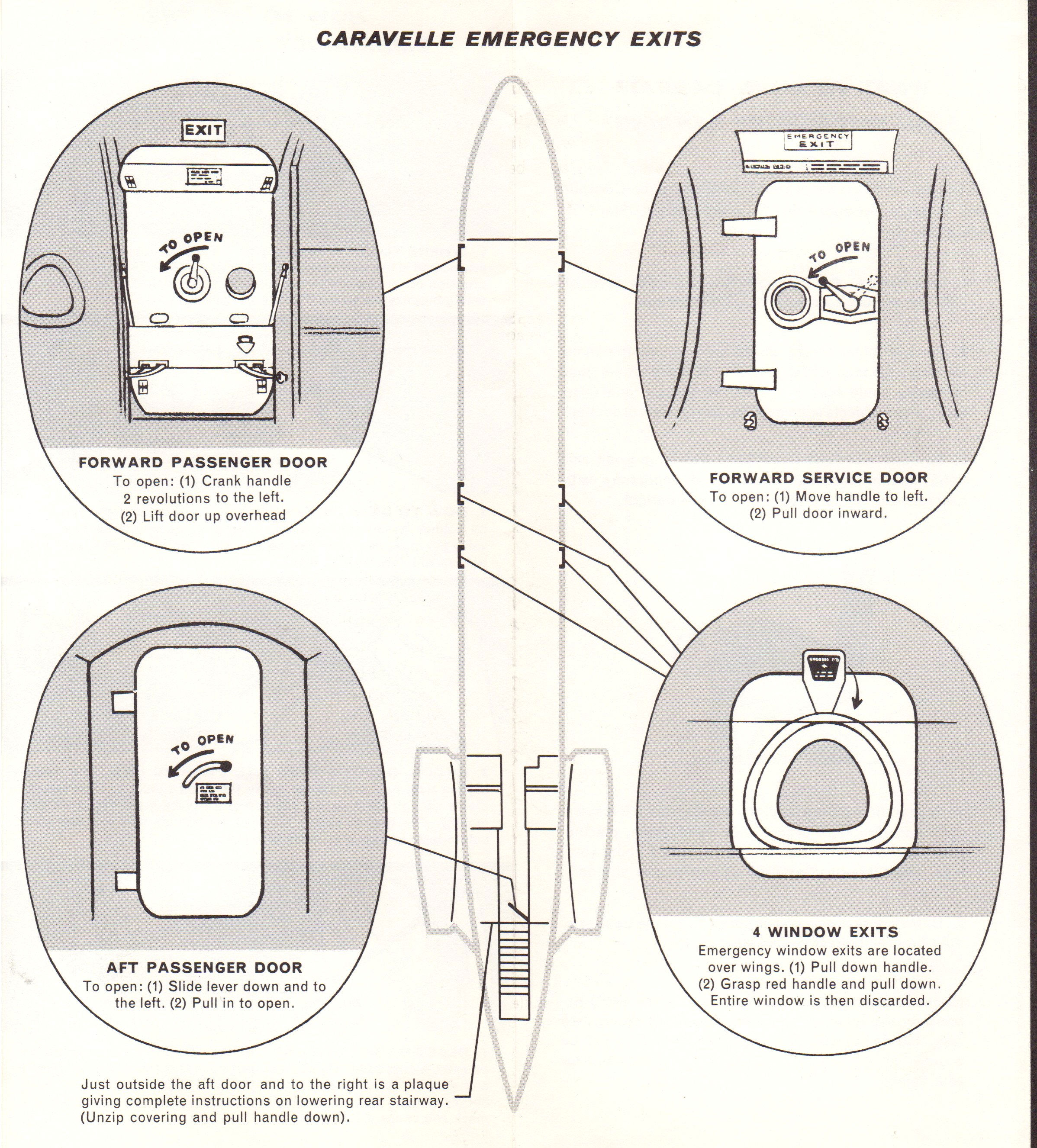

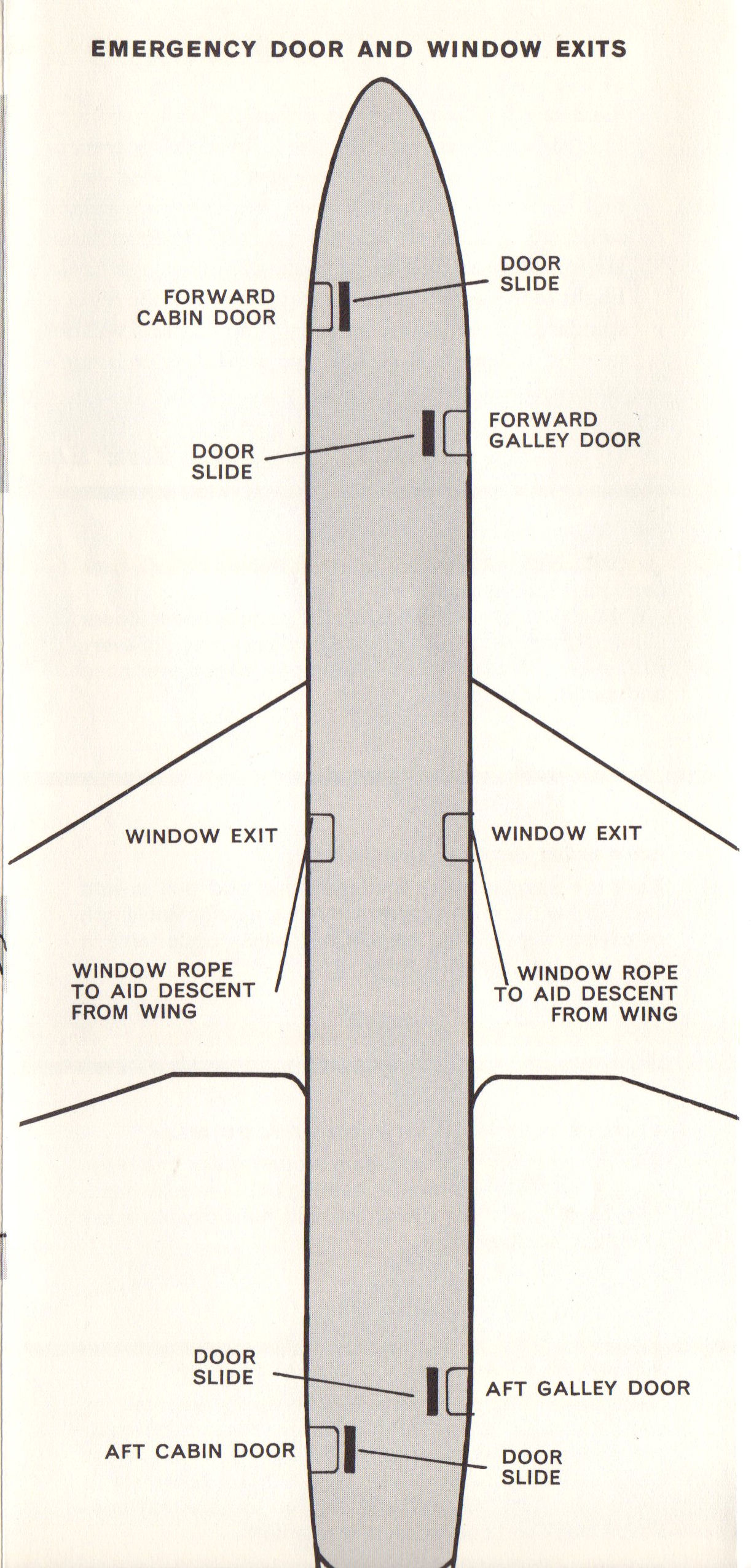

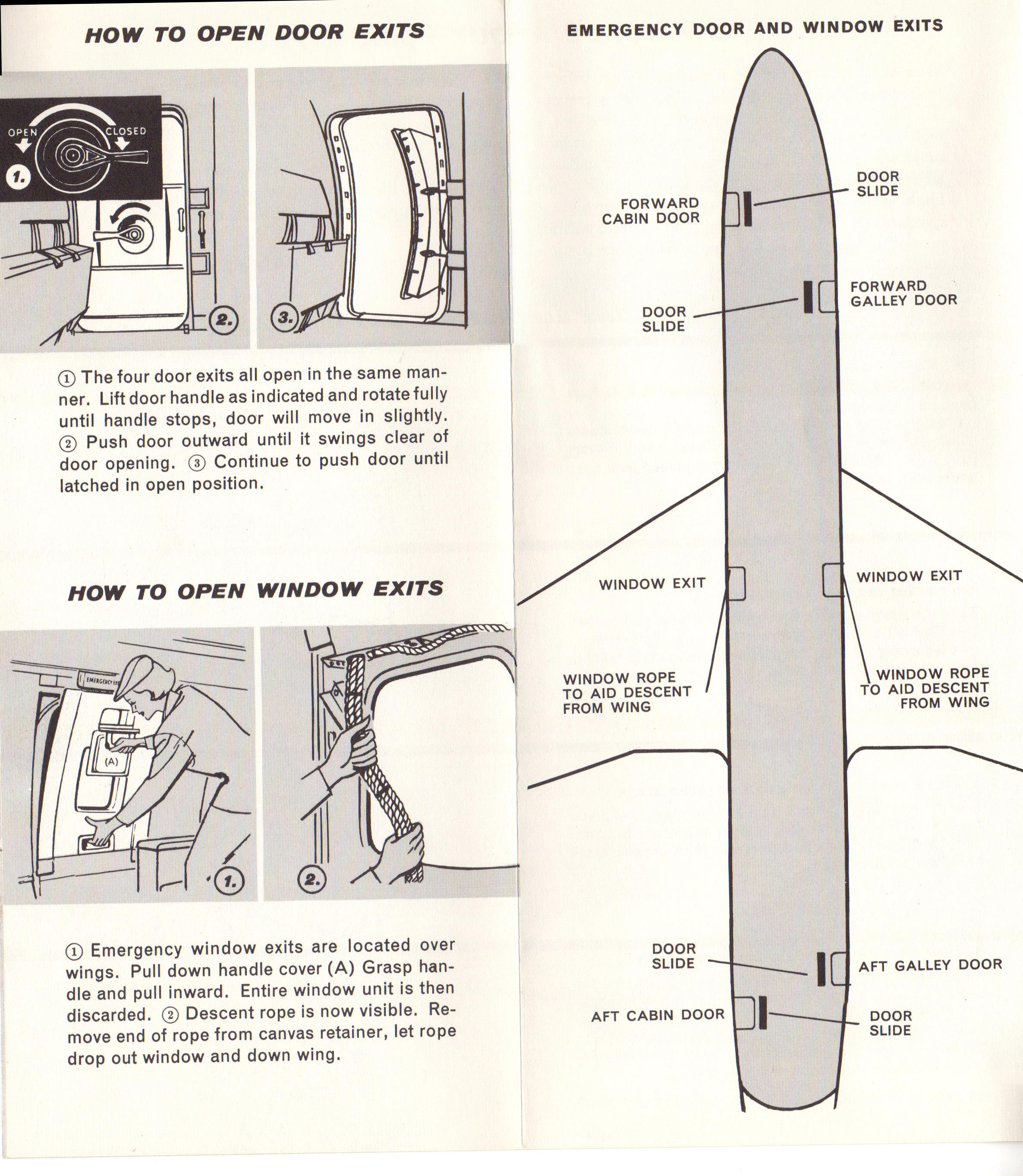

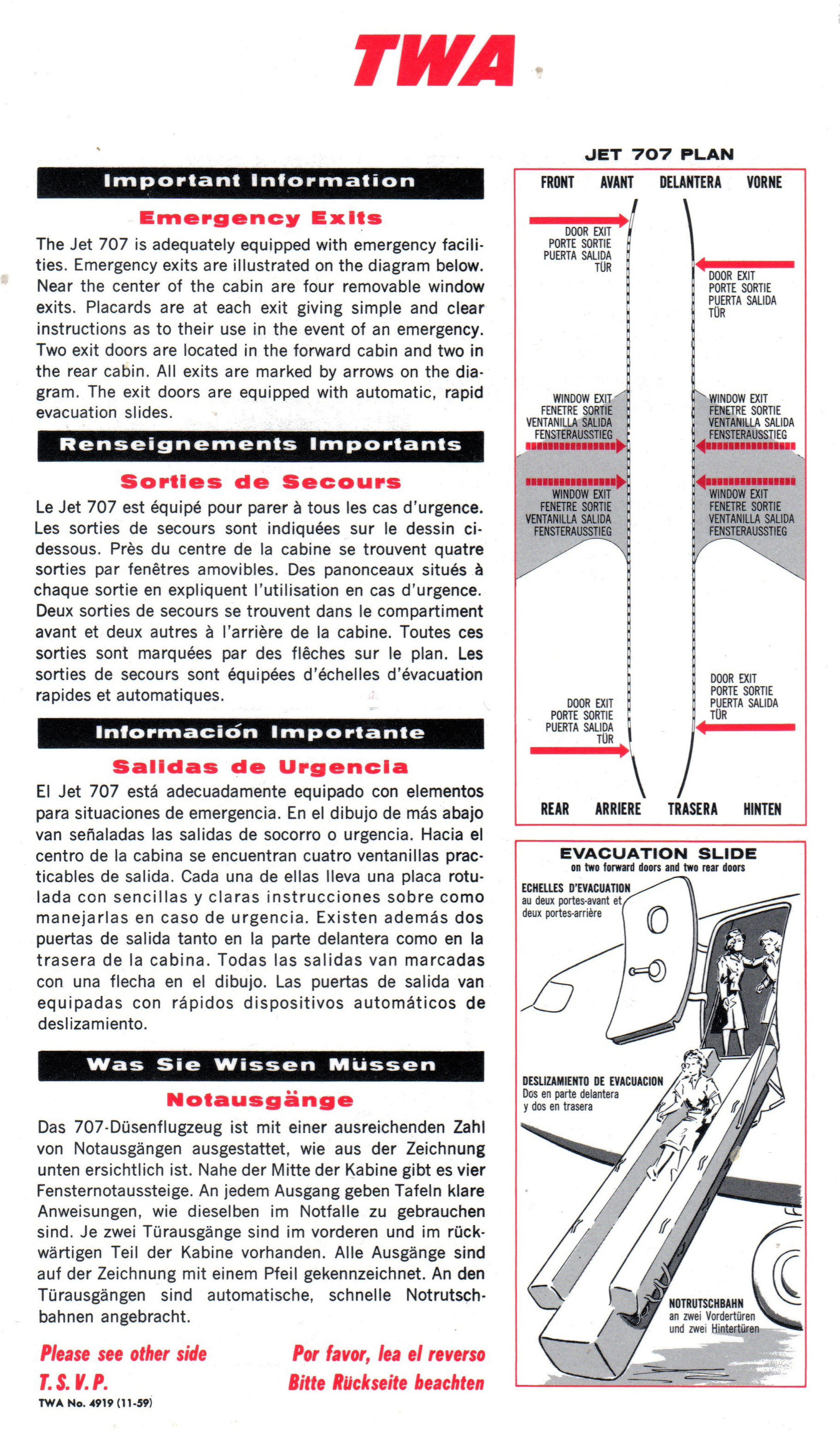

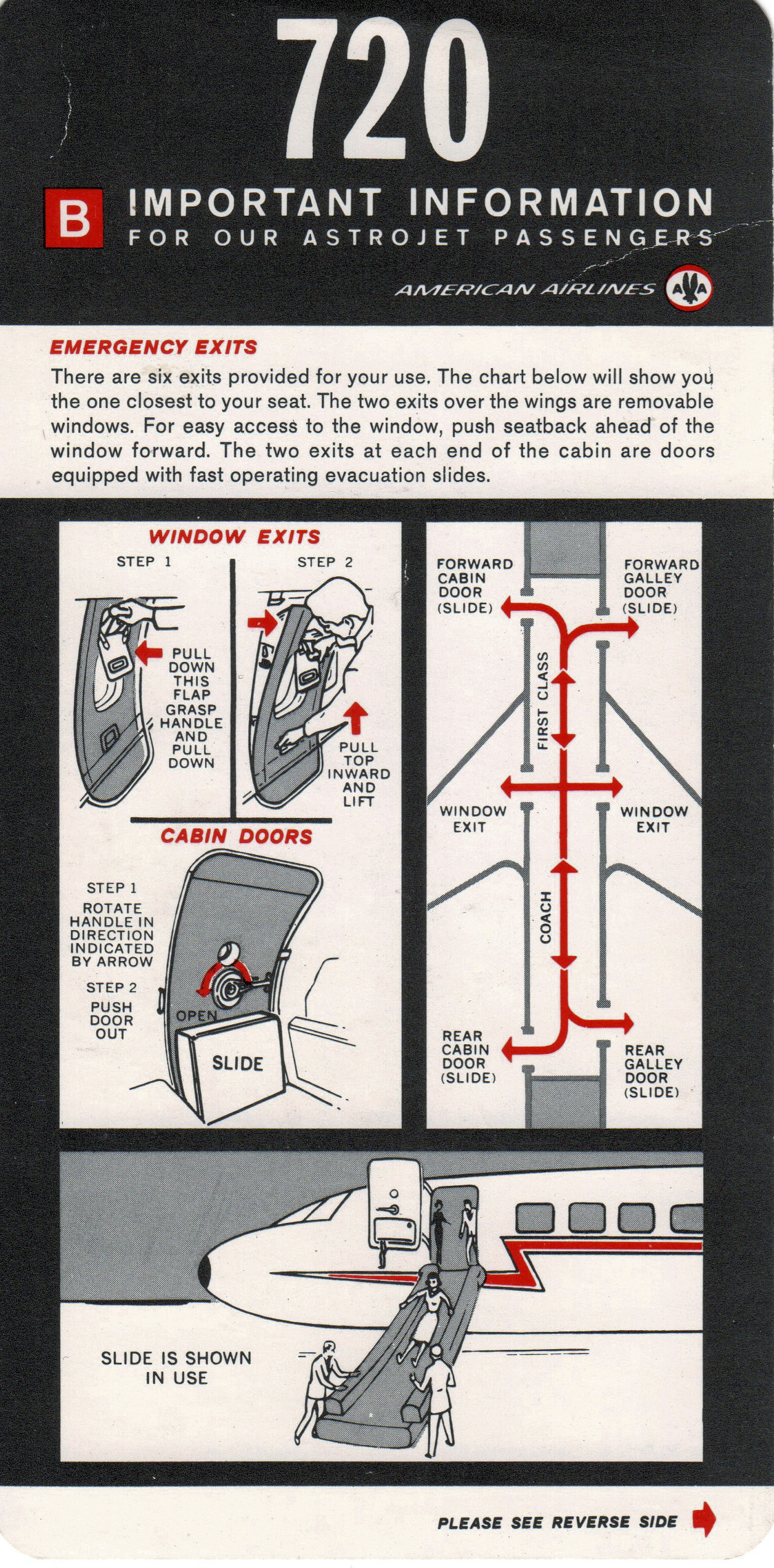

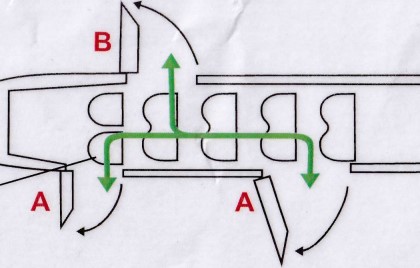

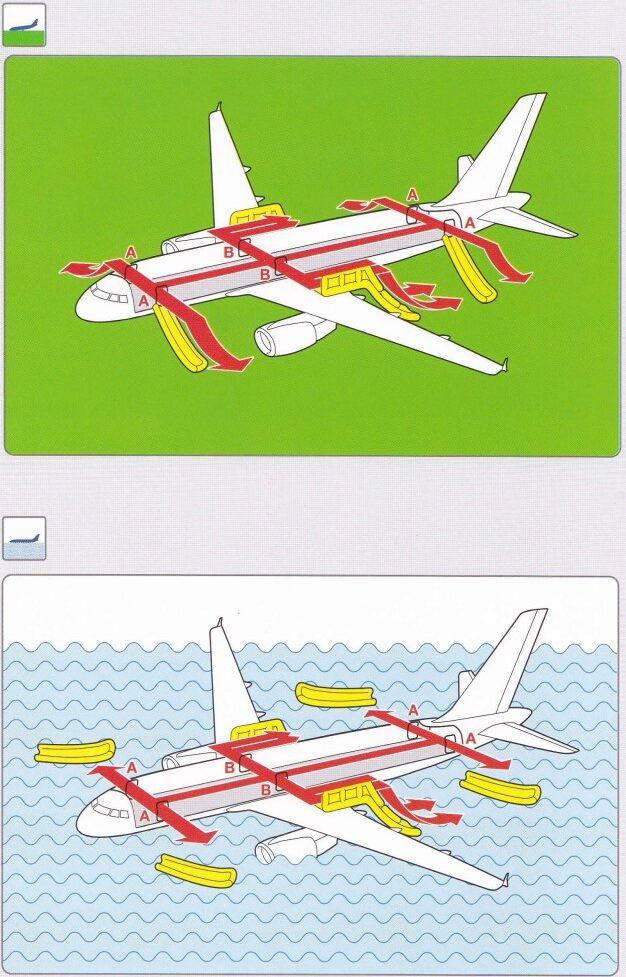

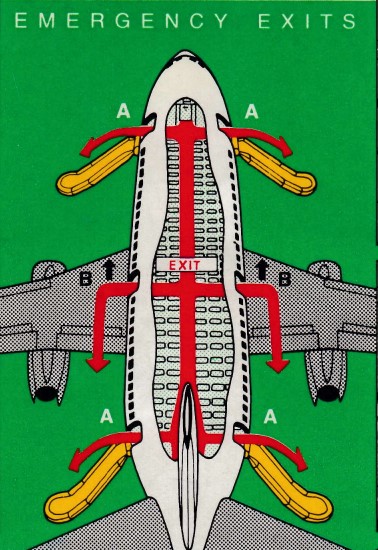

Instructions for escape on the ground typically address four elements: (1) the path from a passenger seat to the exits, (2) the locations of the exits, (3) the opening and use of the exits, and (4) the use of a slide or other descent device.

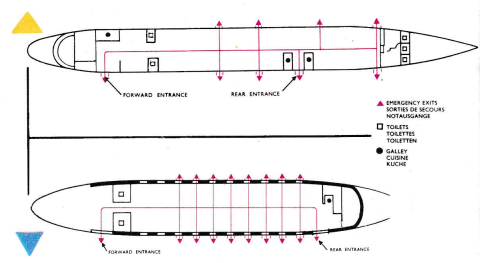

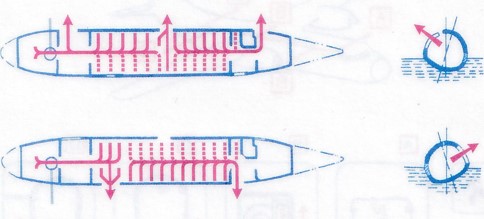

Path to the exits

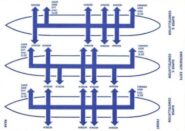

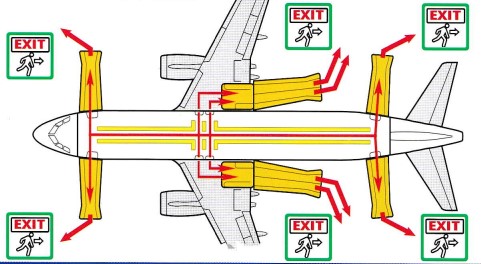

The escape path from a passenger seat to the exit is formed by the aisle, the same as used during normal operations. Many cards show a diagram of the airplane revealing the aisle, or aisles in the case of a wide body. An aisle is typically identified by a red line (rarely, it is green or another color) leading to and through the exits. For twin-aisle airplanes, some airlines identify each aisle, while others do not care and show one line symbolizing both aisles. American Airlines shows something in between. Some airlines go further and show in their diagram the floor-mounted emergency lighting which runs along the aisle, with offsprings in exit rows. Where the airplane diagram does not show the floor lighting, often the card has a separate panel explaining it.

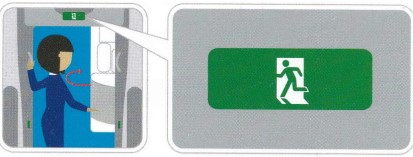

Exit signs help passengers identify where the exits are. The only cards I am aware of showing them are those of the Boeing 787. This airplane type has the symbol of the green running man instead of the traditional red, lettered, EXIT sign which is common in the U.S. To explain the symbol to the American audience, the FAA required the safety card explain it. Other countries, even those where the green symbol is very common, adopted this condition. EU country Poland is an example.

The largest airplane without an aisle is the Trislander, a development of the ubiquitous Islander. In its absence, it has as many as five emergency exits for 16 passengers. Each exit serves one or two rows, as Aurigny (the Guernsey airline) correctly displays. Other Islander users such as OFD, which serves the Frisian islands of Germany, incorrectly suggest there is an aisle.

The overall airplane diagram often is a bird’s eye-view rendering from the left front. Another way to show the aisle and exit location is a top view, either displayed horizontal or vertical. In 1984, Transavia rarely rendered an elevated view from behind.

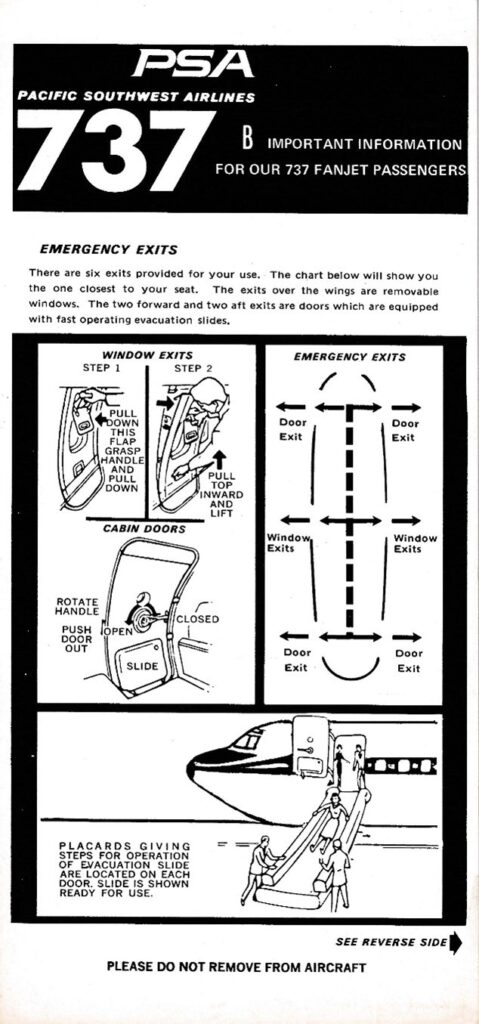

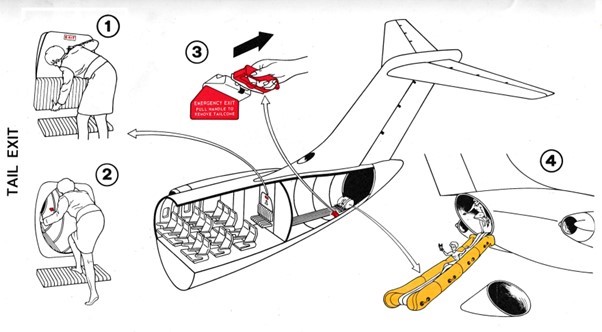

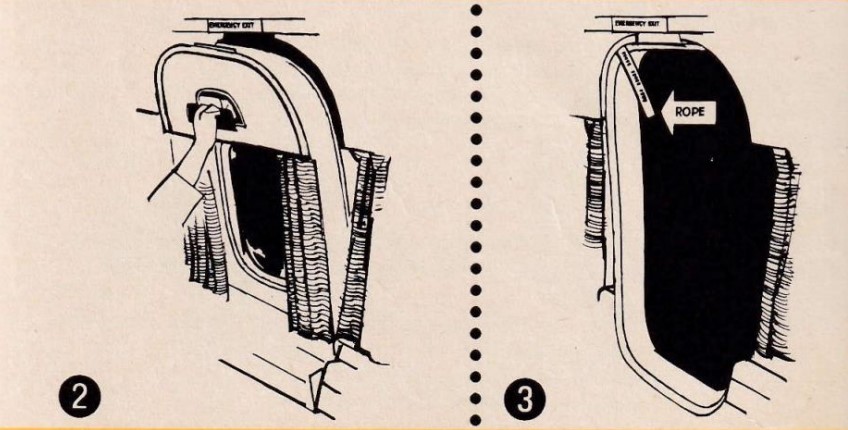

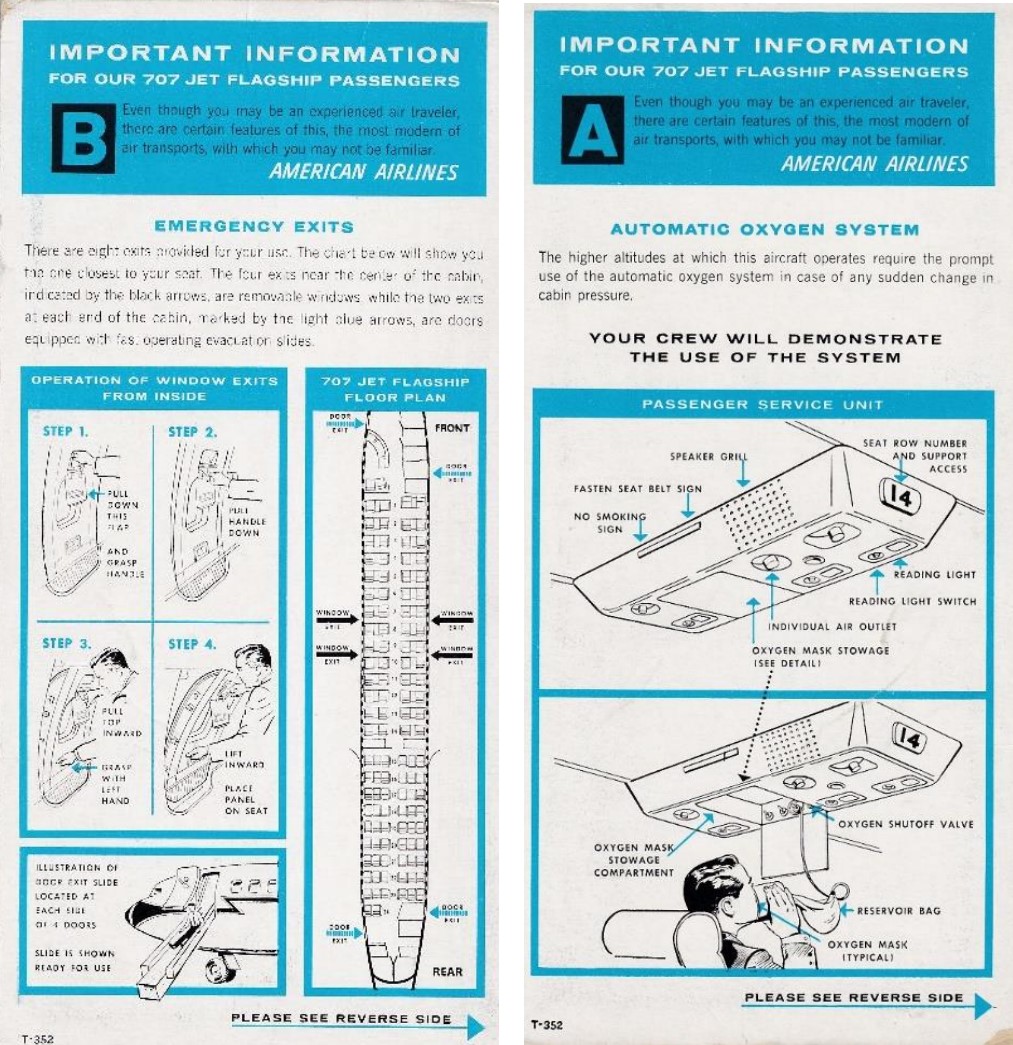

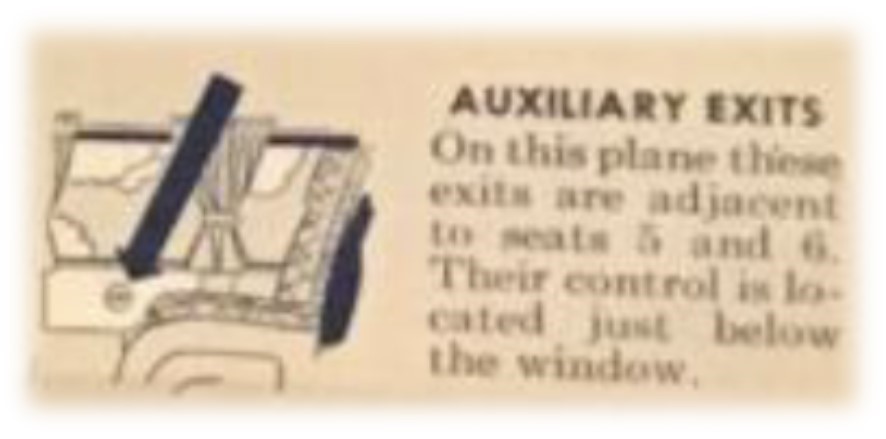

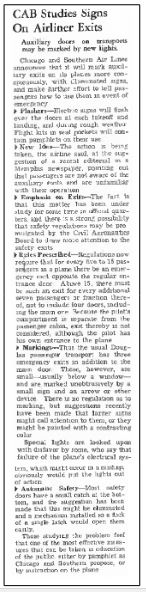

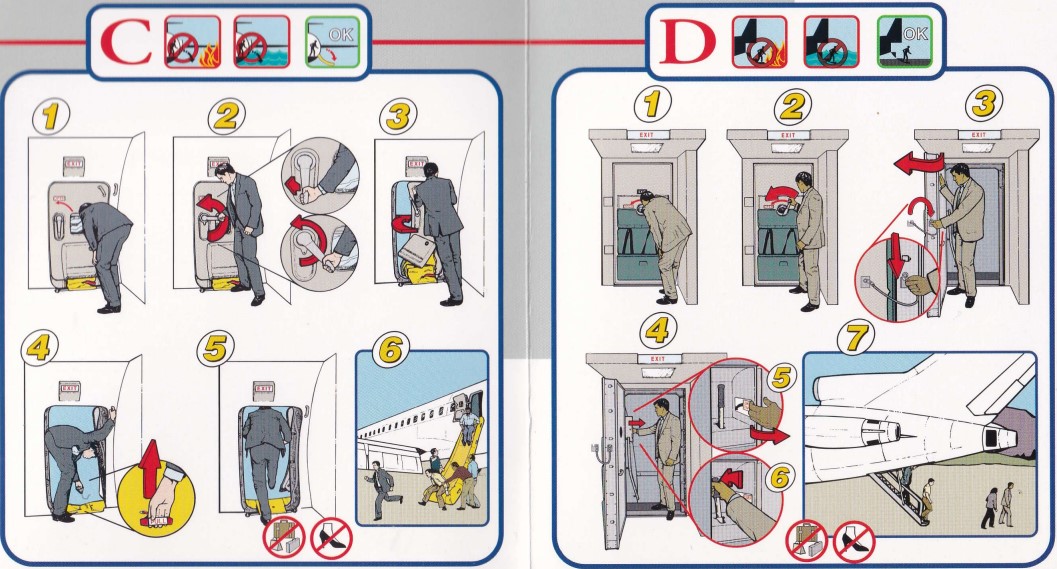

Exits

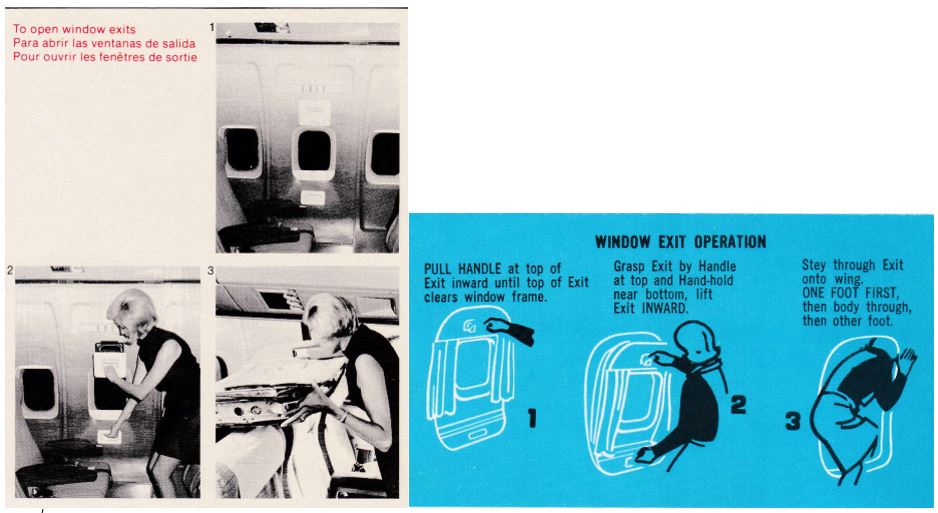

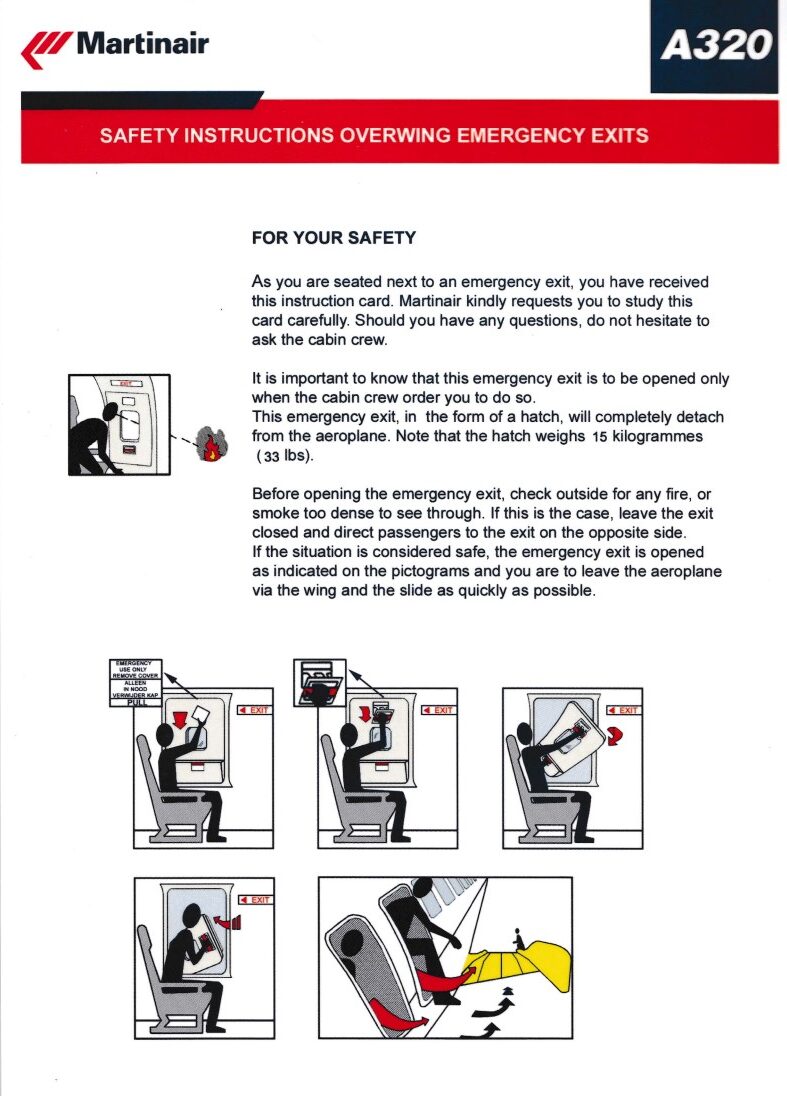

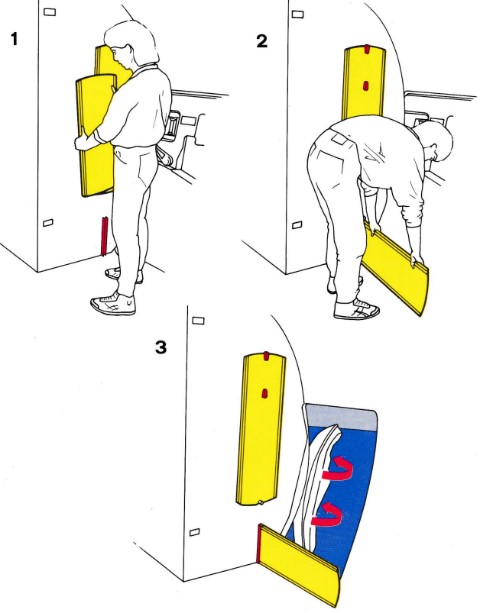

The next step in the escape journey to outside safety is the exit, where the main challenge is how to open it. Airliners typically have two kinds of emergency exits: non-floor level exits which are located in passenger seat rows, and floor level exits, where cabin crew sit adjacently. The non-floor level exits are always located over the wing and have a hatch that comes free from the fuselage. It is to be opened by a passenger and is therefore also known as a “self-help exit.” The exits with cabin crew next to them consist of a door, often of the hinged type.

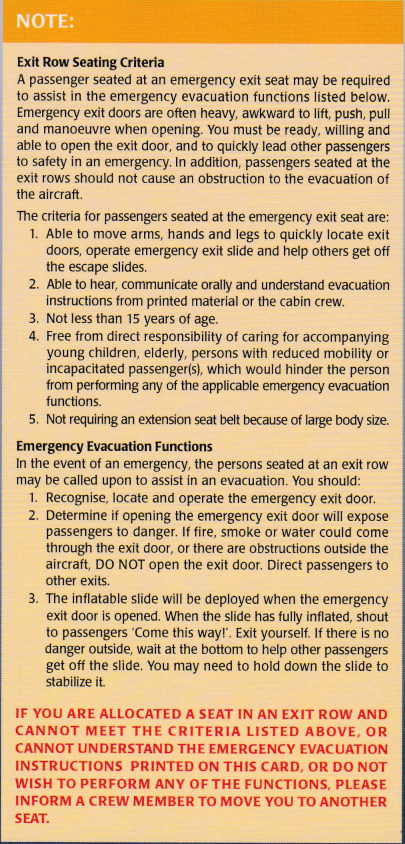

Particularly for the first category, the hatch-type exits, instructions vary significantly. Until the mid-1980s, these exits were underrated on safety cards. But an accident on a Boeing 737-200 in Manchester, UK, in August 1985 revealed these exits are vulnerable to passengers not knowing how to open them. This highlighted the importance of properly instructing passengers seated adjacently. Some airlines, mainly in the UK where the accident had happened, ordered cabin crew to verbally brief those passengers before the flight. Other airlines, in Europe and beyond, introduced separate cards with detailed instructions, only given to passengers in those rows. They form an interesting find for collectors.

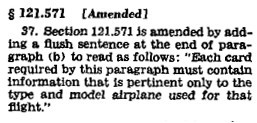

In yet other cases the all-airplane cards are enhanced with detailed overwing exit opening instructions. In the U.S., as discussed in Part 6, the cards display criteria for who may sit in those rows. Where in most cases the cards explain how the exits are opened, U.S. cards focus on who may open them.

The hatch-type self-help exits that come completely free are not ideal, especially when they are heavy. They can weigh as much as 30 kg/66.14 lbs (on a 767). This important information is rarely mentioned on the card. Gradually, airplane manufacturers applied designs where the weight of the hatch no longer needed to be negotiated by the passenger. They hinge open and thus require less of an effort. The first airplane type so equipped was the Boeing 737 New Generation in the late 1990s. More recently, new types such as the Airbus A220, Embraer E2 and A321neo are also so equipped. More often than not, the hinge feature is not well shown on cards, but Panamanian carrier Copa does this well.

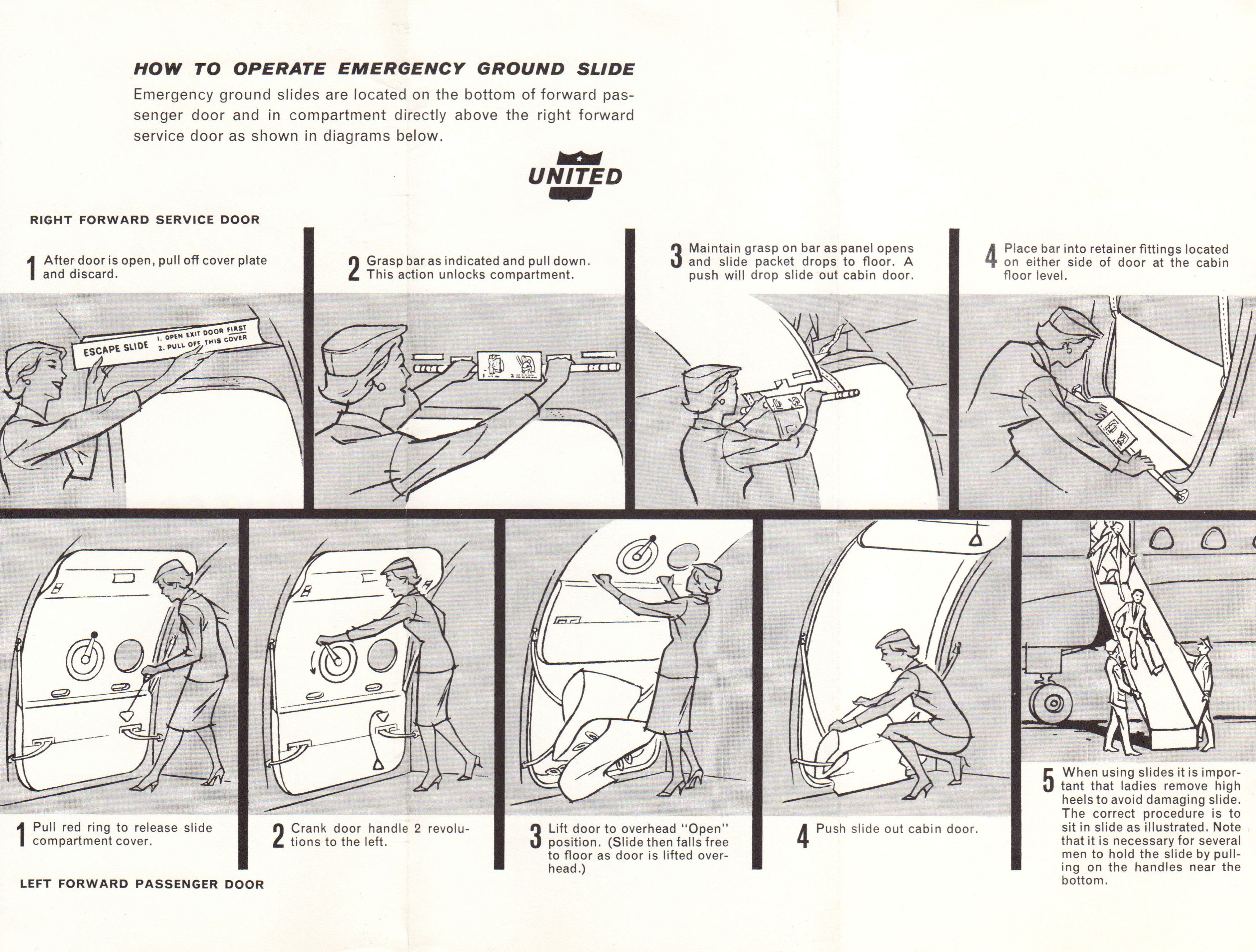

While the self-help exits are in view of the passengers, the door exits often are not. They are meant to be opened by cabin crew. However, safety cards still show how to open them. This is to cover the remote case that cabin crew are unable to do so. Some airlines do this in an abbreviated form, but companies that make cards for a living take pride in explaining every step. For older airplanes, this amounted to up to six or seven steps, such as shown on a Falcon Express 727 card.

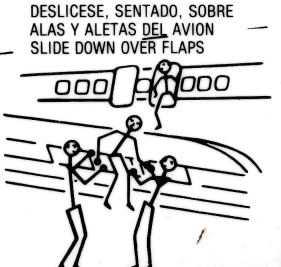

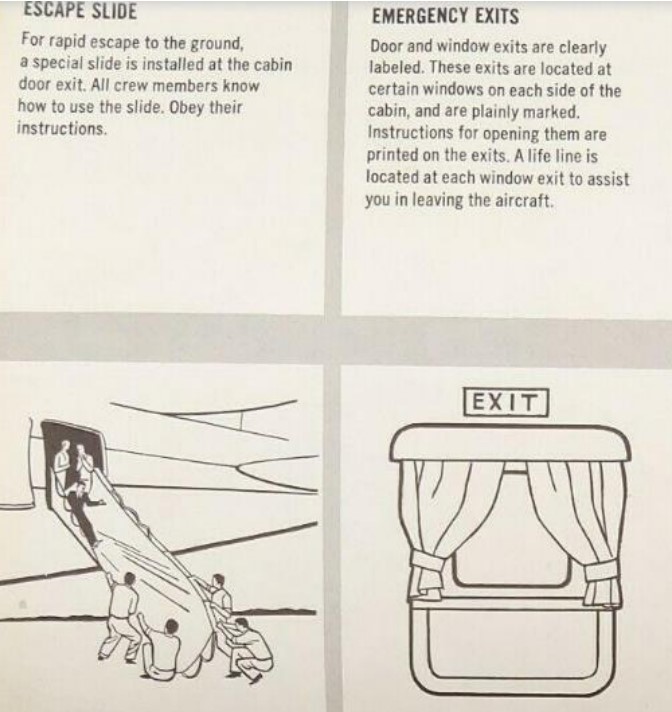

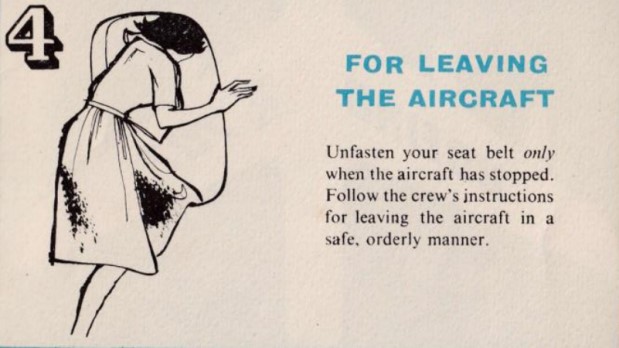

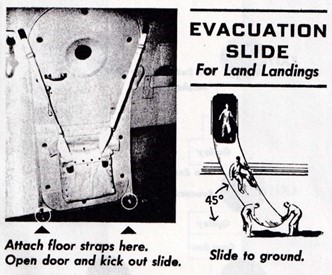

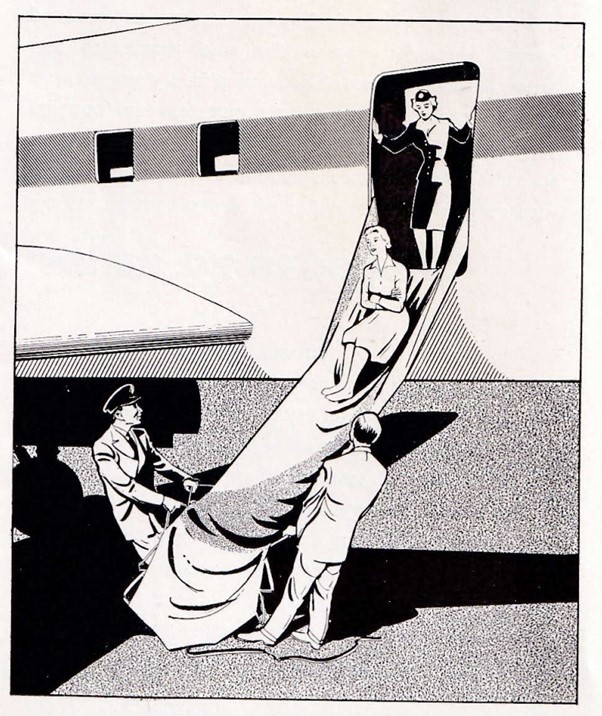

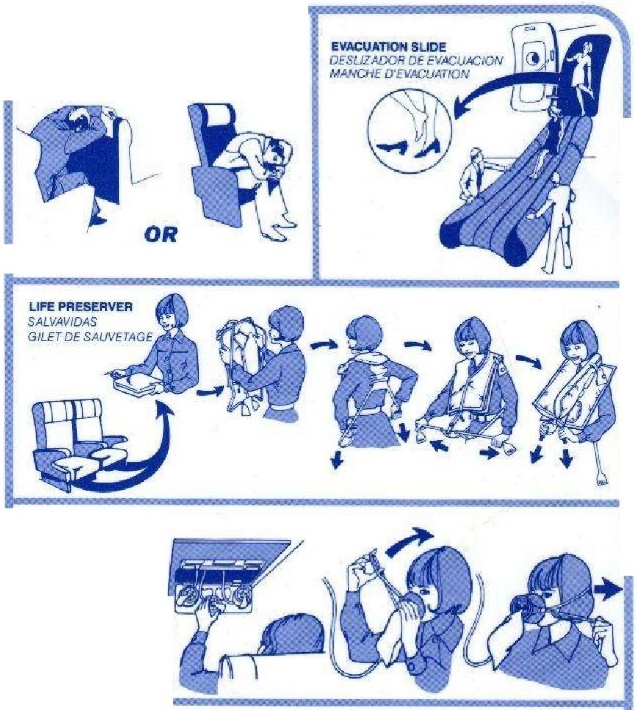

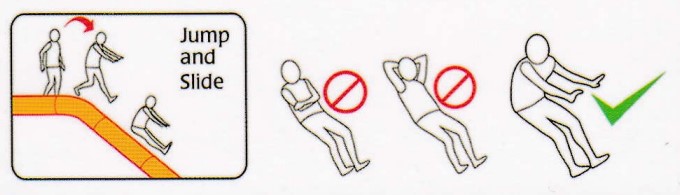

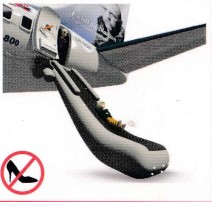

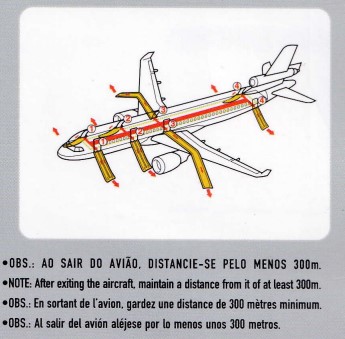

Slides and Other Descent Means

On all airplanes where the exit sill is higher than 6 feet (1.8 m), there is a slide or an alternative descent means such as a set of steps. Similarly, where the escape route over the wing exceeds this distance, off-wing slides are provided. Cards show these slides twice: on the airplane diagram and in a close-up meant to emphasize their proper use: jump into the slide rather than sit on the sill and then move forward. Few airlines manage to convey this clearly, but Singapore Airlines’ attempt is a good one. The most dominant color of the slide on cards is yellow. However, since the mid-1980s, when it was found that an aluminium coating would make the slide more fire resistant, they are actually silver or grey. Some cards correctly represent this, but many still show yellow.

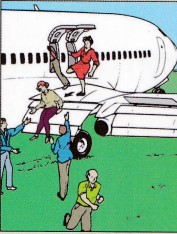

A good post-sliding practice for evacuees is to move away from the airplane. Very few airlines show this. I found one where the text instructs passengers to move away at least 300 meters. On propeller-equipped airplanes, a warning to stay away from the propellers is common.

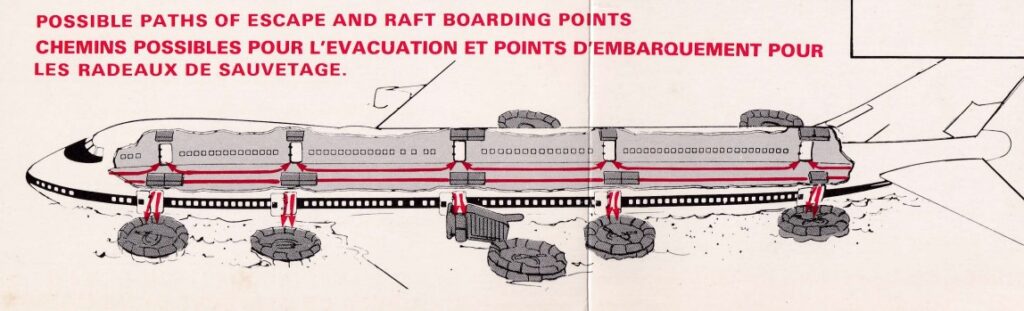

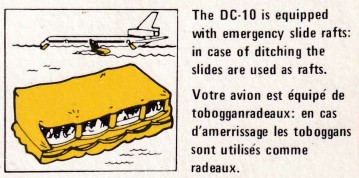

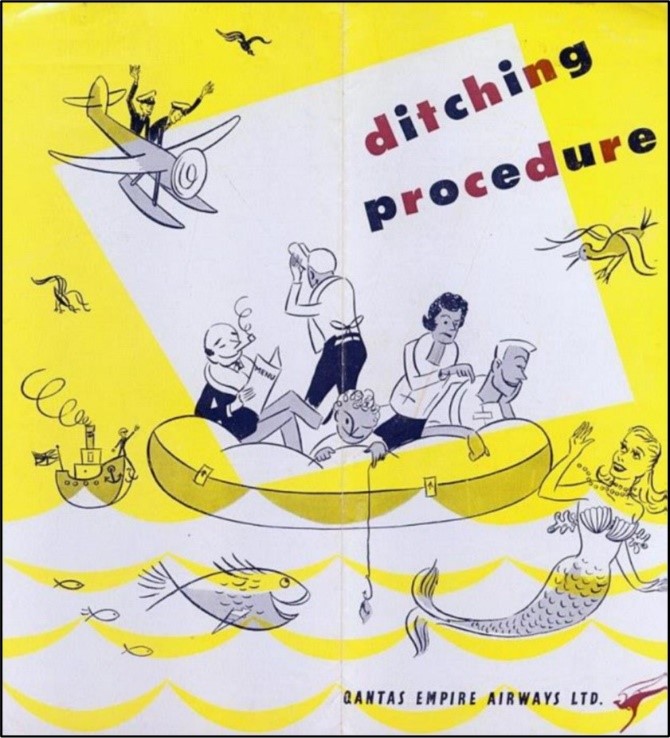

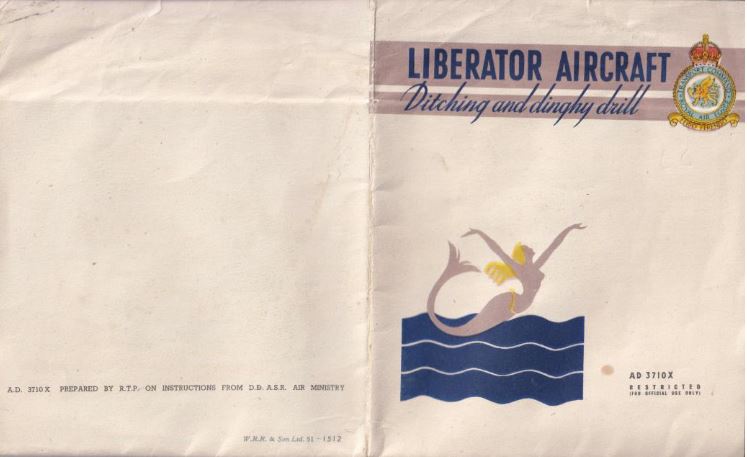

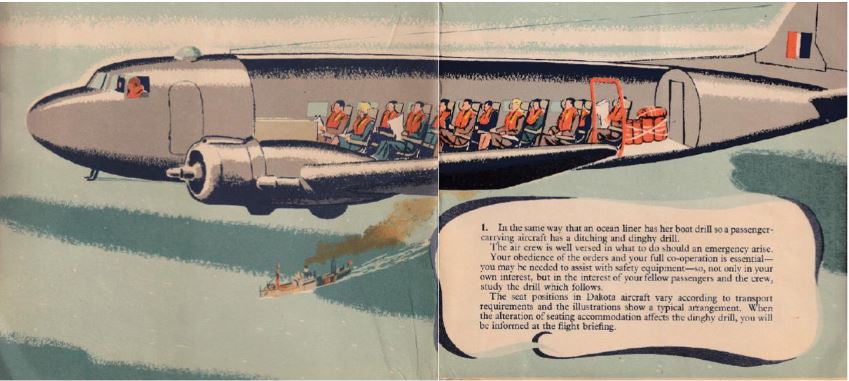

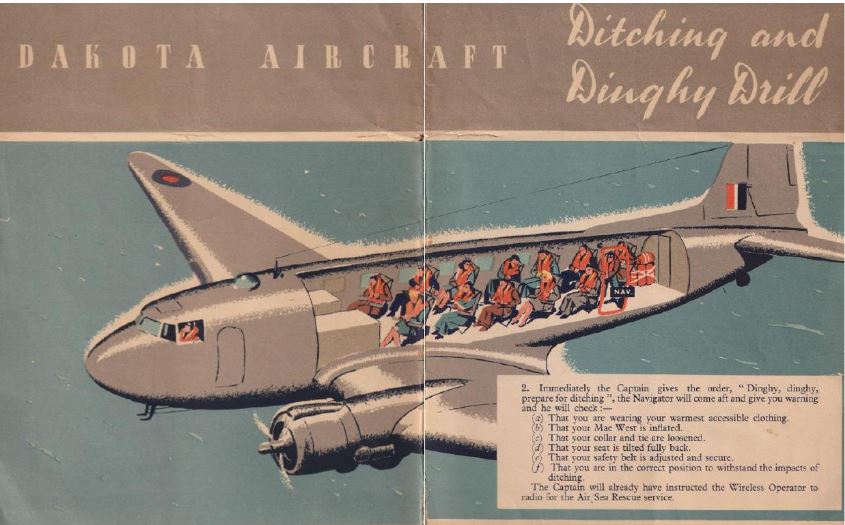

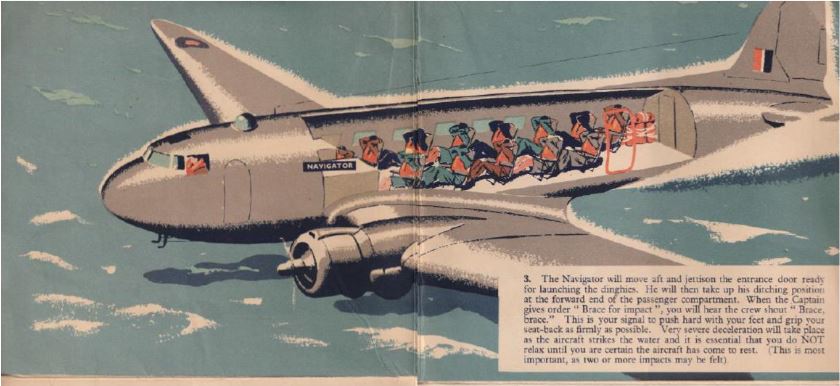

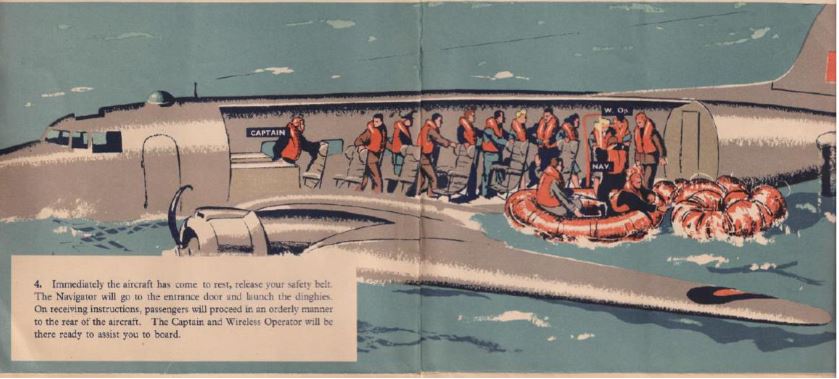

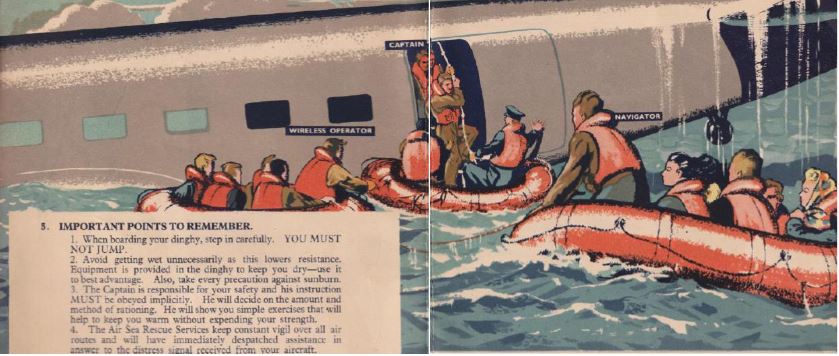

Evacuation and Survival on Water

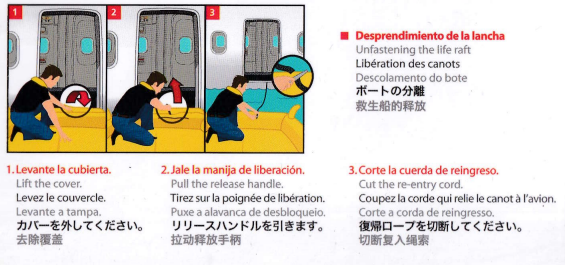

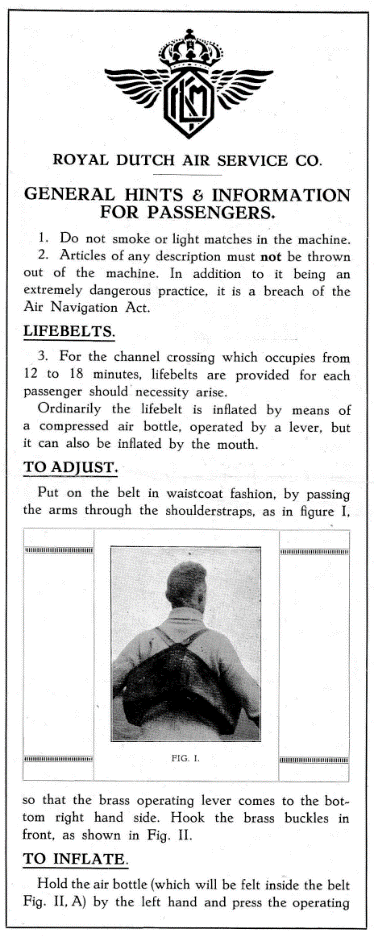

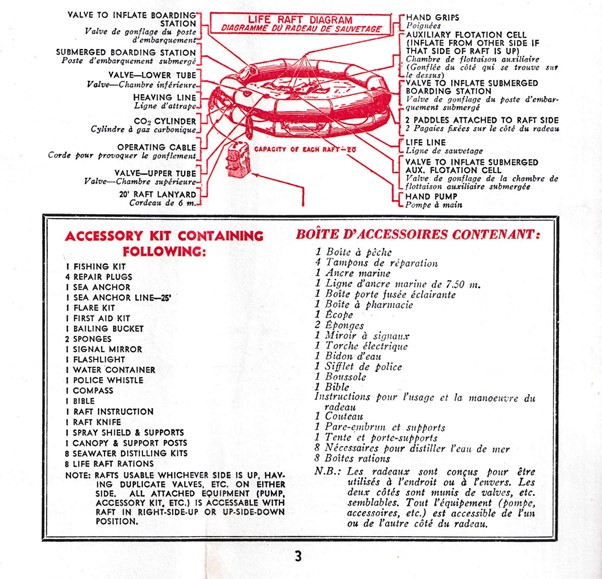

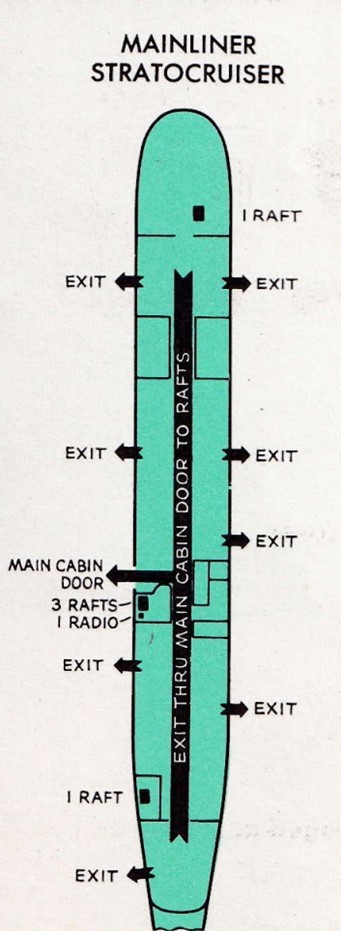

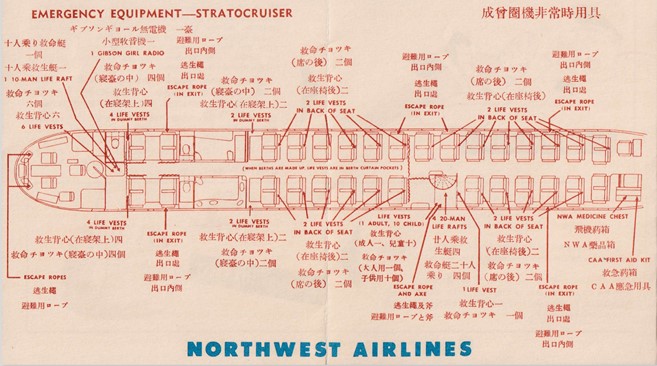

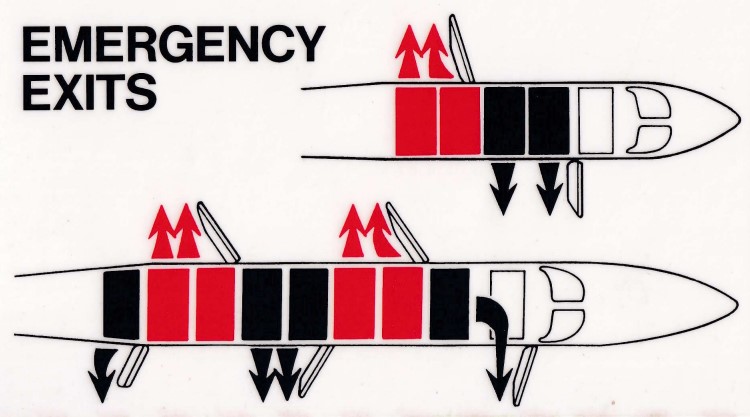

Much of what is described above, also applies to the emergency scenario where an airplane has come down in water. But there are differences: some exits cannot be used as they would be below the (theoretical) water line, life vests are provided for individual flotation and for collective flotation the slides can be used. On twin aisle airplanes the slides are formally certified for that use and then called slide-rafts. Some airlines still use separate rafts.

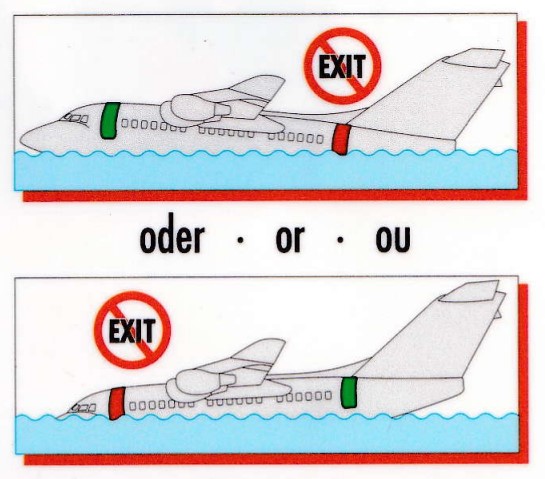

Many cards dedicate a separate section for the water scenario, displaying an airplane diagram similar to that for the land scenario, but now with a blue background instead of green or blank (see Czech Airlines above). Typically the same exits are shown. The slides now float, serving as rafts. For some aircraft types, the diagram shows blocked exits as they will not be above the waterline. This applies to most high-wing airplanes such as the Antonovs, ATR 42 and 72, Fokker 50, Dash 6 (Twin Otter), Dash 7, and some Dash 8 series. The high-wing BAe 146 has a different flotation pattern, as its cards show both aft exits as unusable as opposed to the forward pair, although one airline admits that the airplane may alternatively float nose low so that the forward exits may not be usable.

As high-wing airplanes would list to one side, with one wing tip down in the water and the other up, they render exits on the low side unusable. On their Antonov-24 card, Air Moldova International shows this nicely with a cross section of the fuselage, but they forgot to add whether the view is looking forward or aft. In the seating diagram they added dotted lines, the meaning of which I do not understand. Any ideas?

On the Fokker 50 and Dash 8 series, even the exits on the high side may be below the waterline. Their manufacturers improvised dams or sill raisers in an attempt to prevent massive water influx during the evacuation. Some of these operate automatically, but the Fokker 50 has loose boards that need to be secured in place before opening the doors. Some Fokker 50 users show them, others do not. The right forward exit of the Q400 has a split hatch. In case of a water landing, the passenger next to it needs to secure its lower part so that it stays in place and forms a sill above the water line. This is shown on the safety card, but I doubt whether naïve passengers will obey.

To my knowledge, these water barriers have never been put to practice as there were no water landings where they could have been put to use.

Interestingly, quite a few cards of airplanes regularly flying over water have no escape instructions specific to the water landing scenario at all. An example are Winair’s Twin Otters that commute between the Dutch Caribbean islands of Sint Maarten and Saba, both prone to an emergency landing on water.

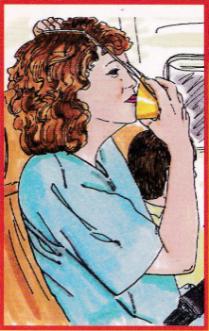

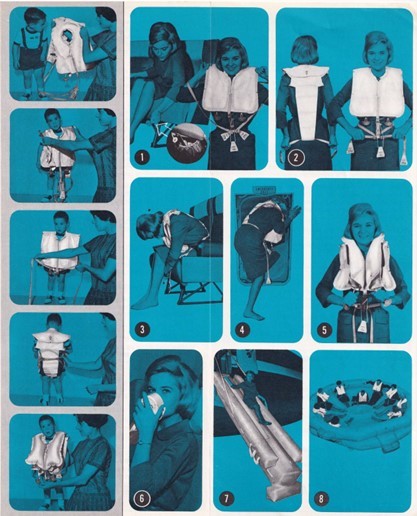

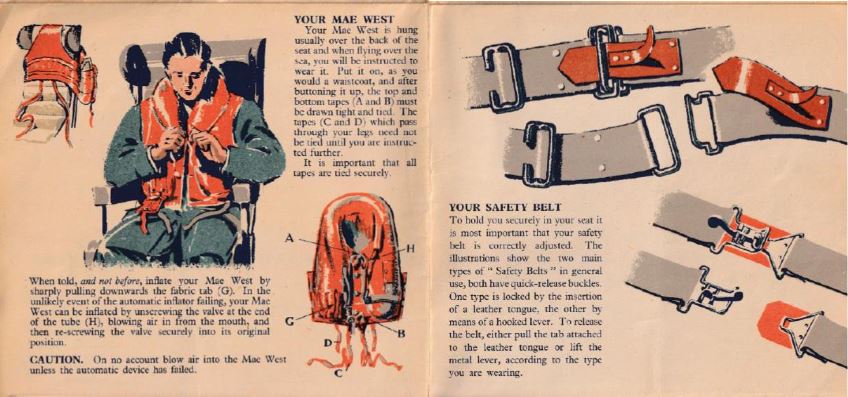

Many cards use a lot of space for explaining how to don the life vest and occasionally that of children and infants. An alternative to life vests are flotation cushions. They are particularly popular in the United States.

They are inferior to life vests as they do not passively support the wearer but require the passenger to actively hold on to it, which in cold water is a challenge. The U.S. fondness for flotation cushions can be traced back to a ditching accident in 1956 near Seattle when a stewardess impromptu advised passengers to use their seat cushions for flotation. It prompted a U.S. requirement for seat cushions to be equipped for such use. On many domestic flights in the U.S., they are the only flotation devices on board. Few airlines have any flotation devices at all. An example is Ethiopian Airlines which does not carry them on airplanes flying only domestically. Ethiopia is landlocked and only has a few lakes.

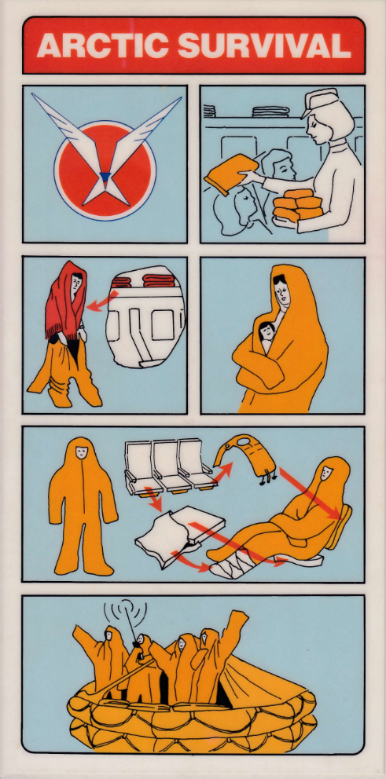

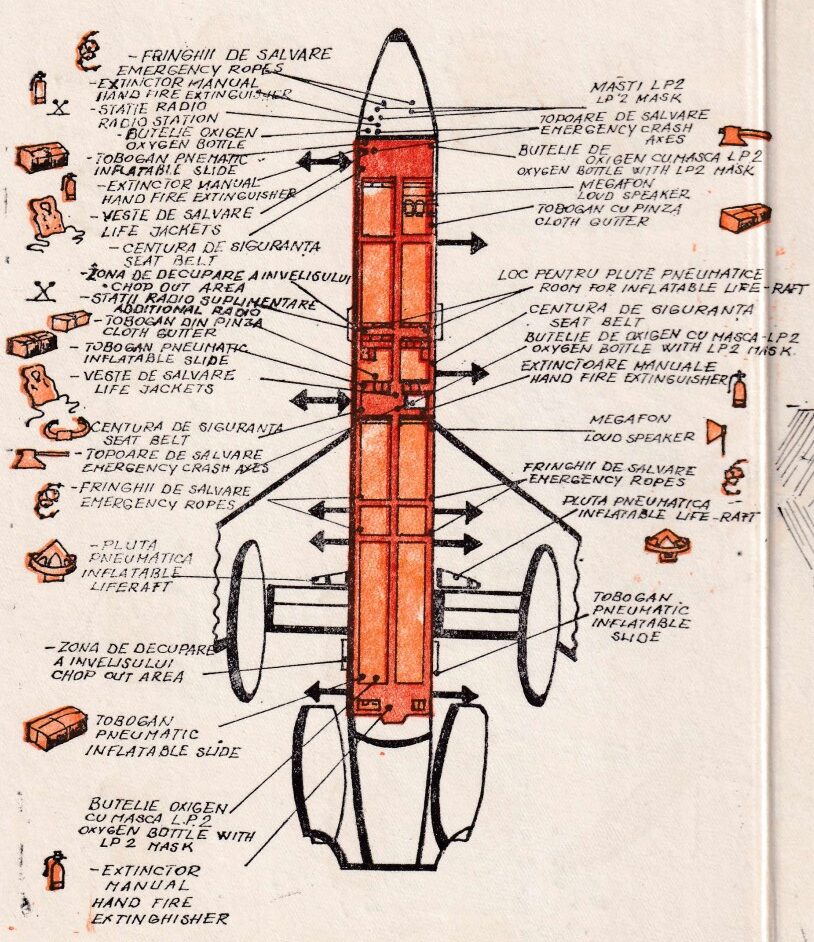

Emergency Equipment

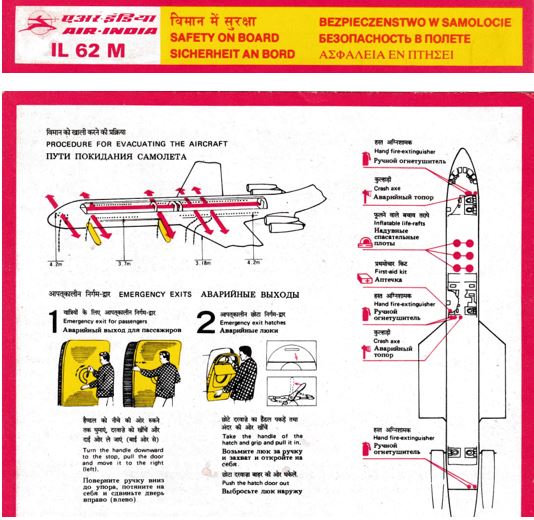

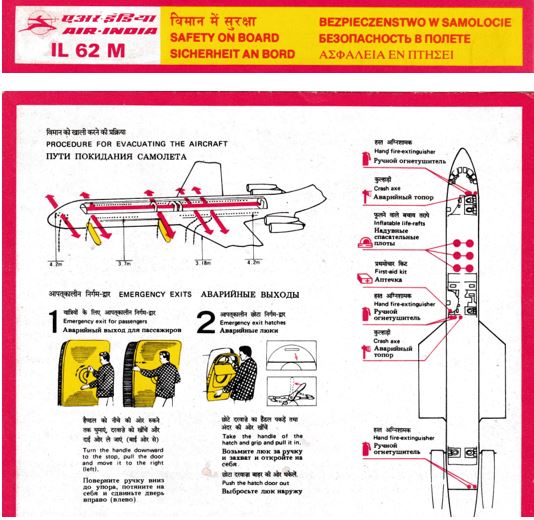

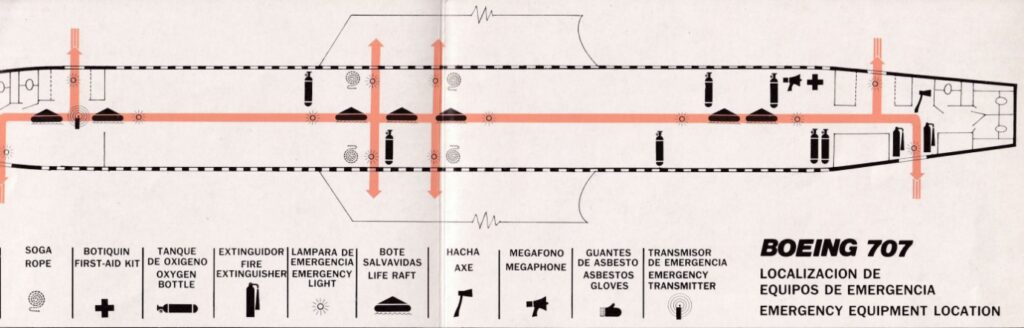

Airlines rarely display other emergency equipment than those described above. When they do, it is for smaller airplanes (where no cabin crew is required) or VIP airplanes. The location of fire extinguishers, first-aid kits, and portable oxygen bottles is then indicated. Russian-made aircraft form an exception. They often have a diagram showing all emergency equipment on board, including axes, ropes, ladders, megaphones, emergency beacons, and transmitters. Although dated, Balkan’s Tupolev Tu-154 1980s card is an interesting example.

Unusual Features

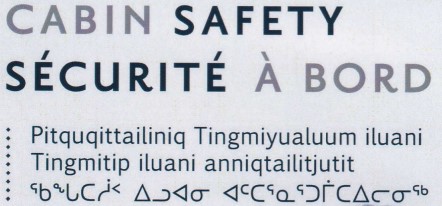

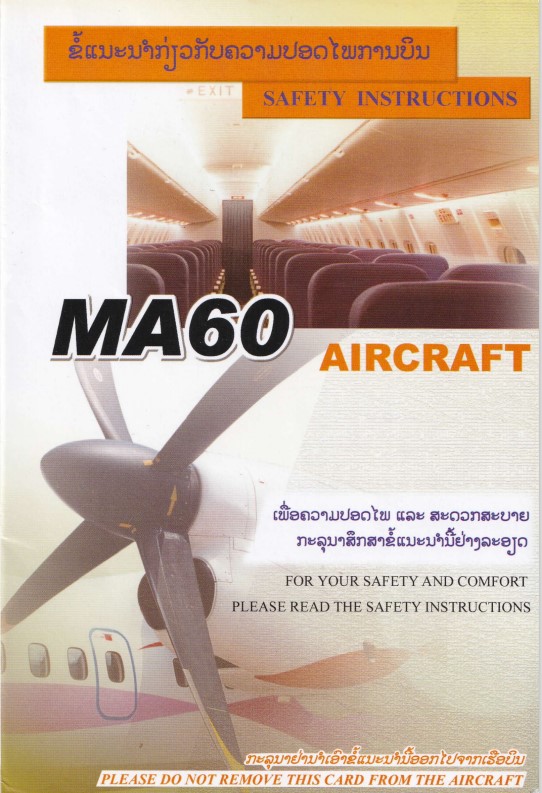

Some airlines add items that are unique or rare, making them special finds for collectors. This includes unusual language scripts. The Latin script is not the only script that is widely used. Arabic, Chinese, Cyrillic, Indic, and Japanese scripts are used by many people and thus frequently found. Rarer scripts include those from Arctic Canada, Georgia, and Laos. They only appear on a few cards.

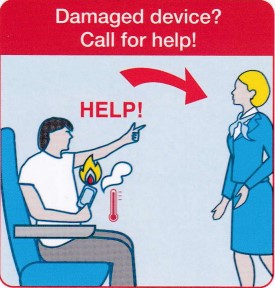

Examples of safety-related unusual subjects spotted on cards are how to use a slide with a child or infant, the prohibition to sleep on the floor, the prohibition to wear nylon stockings (for which the card is too late, as the passenger is already on board and will not change), or what to do if a smartphone is lost in a seat, or damaged.

Other finds include a person reading the safety card, information about service initiation and termination times, and a warning not to take away life vests.

Following a 2003 federal law, U.S. safety cards must mention the airplane’s country of assembly. The aim is protectionist: discourage imports from outside the U.S. (and specifically Airbus aircraft from Europe). But the world is not black-and-white. The rule backfired when, in 2016, Airbus started an assembly line in Mobile, Alabama, negating its original intent. As more and more aircraft are built there, safety cards saying the final assembly of an Airbus was in the USA become less unusual.

On a final note, I invite collectors to examine their safety cards and report which unusual features their collections hide.

Fons Schaefers / November 2024

e-mail: f.schaefers@planet.nl