Written by Lester Anderson

[All photography from Wikimedia Commons.]

I live about three minutes from touchdown at Newark Airport for a few approaches landing to the south. I know this because I follow the overhead aircraft on my phone with Flightradar24. I enjoy seeing from what airport the aircraft was arriving, the type aircraft and its altitude and speed at that moment. Since the virtual shutdown of air travel due to the COVID-19 virus I see almost no traffic overhead. A large percent of what I do see are freight carriers (UPS and FedEx both have major hubs at EWR) since passenger flights are rare the freight is much more likely to be on one of those carriers with their expanded schedules.

But I love flying (as a passenger, I am not a pilot). So, what is there to do? My solution is to think of the “good times” of travel in the past. Besides the actual flights, a lot of my memories concern the airports from which I departed and at which I arrived.

I once attended to a dinner where one of the guests had just been “retired” from a position with a large bank. She said she had no regrets about being “reorganized out” because the bank gave her the opportunity to travel the world, stay at the best hotels, and eat at the finest restaurants. In my case, I thank all my former employers for giving me an opportunity to enjoy my (over one and one half million miles) of business travel by taking the flights I wanted, with my careful watch (and working with corporate travel) to cost the company no more that standard routings would cost the firm. If I had to watch any travel expense, for me it was the hotel or restaurants, which I would gladly do to get the airplanes and airports I wanted.

I write these musings with the hope that while you may not have memories of these specific airports, they this will allow you to think back on your own enjoyable experiences in travel. Some memories go back to the 1960’s, my high school days, but most are in the 70’s 80’s and 90’s.

The East:

I grew up near Newark airport and was a frequent visitor. In those days there was only one terminal, and flight announcements were not posted on a board – they were announced over a PA system. Being curious, I looked around (and probably asked someone) and found the “closet” in which the woman (it was usually a woman’s voice) sat in front of a microphone announcing what gate a Braniff or Eastern flight was departing from, and the cities to which the flight would travel. Electronic displays today are probably more efficient, but there was something really nice about a real person giving you the instructions on how to start your trip.

Newark has grown. I remember when there were working terminals A and B, with Terminal C mostly built, but not yet occupied, and the tarmac was not even finished—grass grew under the gate areas awaiting an airline to occupy it and need the gates. When that happened and PEOPLExpress leased it, a lot of the existing terminal was torn down to build a much larger terminal facility as Terminal C.

In Washington DC, I recall visiting when they first opened the first Metro line to Washington National (now Reagan) and looking at the airport from the elevated train platform. I realize it may not have been efficient, but the old DCA terminal was a beautiful building that brought me back to an era before my own time, where air travel was something that was very special. The other DC area airport was Dulles where the mobile lounge was the way you left the terminal to either go directly to an aircraft or to go to another concourse. I never had the travel experience where the mobile lounge brought me directly to the airplane, but I used it as the way to get to a midfield concourse where my United gate was located.

On one business trip I remember landing in Cleveland in what I would consider an almost white out condition. The snow covered the tarmac, and everything was white. We landed safely (and with complete faith in the crew), and when I was met by the business associates, and trudged thru snow to the cab, I was told not to worry—it is only “lake effect snow”. In New York such a snow event would have shut – or at least slowed down – much of the city. But everyone (including the taxi driver) took it all in stride and did not allow the lake effect snow to slow us down.

The South:

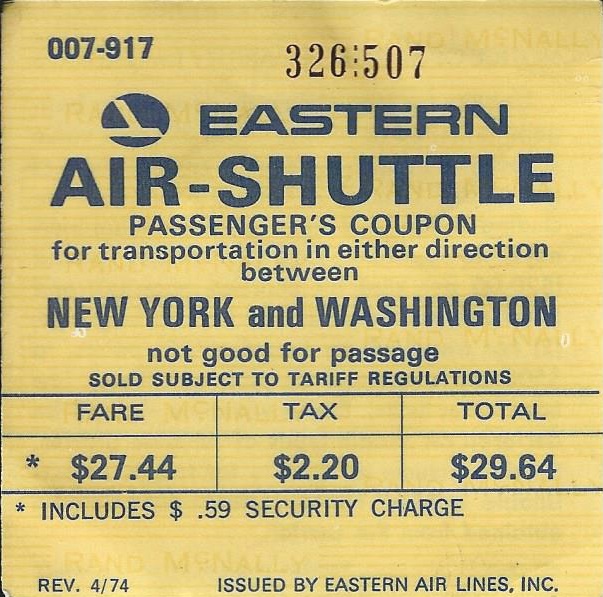

With the hub and spoke airline route system, if you went anywhere in the south, odds are you were going to change planes in Atlanta. I did a lot of flying on Eastern, and they had two concourses, and there was a walkway (you walked under the aircraft gate and taxi area) to the next concourse. From what I read, while it has been closed off, they never filled it in so if ever needed in the future it can be reopened. A pleasant aircraft memory was at Eastern, for a period of time, DC9’s and 727’s would not use a tug to back out of the gate, but a power pushback using the aircraft’s engines. I am sure it was used elsewhere but I remember it often at ATL. The airport’s five concourses were connected with an underground subway system that for the early years (at least a dozen) had a computer voice announcing what concourse you just arrived at and the next one coming up. The voice was a computer voice that was reminiscent of the science fiction movies of the 50’s and 60’s. Fortunately, a more normal voice system was later installed.

Dothan Alabama was my first trip to Alabama (I was working for Sony and we had a videotape manufacturing plant there). It was a small airport with only a few flights a day. The policeman in charge locked the terminal between flights, and if you arrived early, there was a couch to sit on outside the door until he unlocked it and you could enter the terminal. This was an early business flight of mine. Republic Airlines had a special fare that for $30 more you could upgrade to First Class. Corporate travel said if I reduced my expense report by $30 they would ticket me. Done deal! (Always good to be friends with Corporate Travel).

DFW was a favorite airport because of a hotel. There was a Hyatt and it was in the middle of the airport itself. You could ask at check in for a room that looked over the runway and if you didn’t mind a little (not a lot) of noise, it was great for those of us who loved planes. I would bring my aircraft band radio and could tune in to listen to the tower while I was watching the planes. And DFW was busy so you had a lot of action to watch and listen to during the stay. And while it was not the cheapest area hotel, it was reasonable and it was worth it because you never had to worry about getting to the airport for your 6 AM flight home.

The Grand Hyatt at DFW Terminal D

Orlando (with the IATA code MCO because the airport started out as McCoy Air Force Base) in its early days was nothing like the complex it is today. It was a smaller facility right next to the “Bee Line Expressway”. The thing I remember most was that although you had to walk to the baggage claim area, which was manual (no luggage carousels), when you arrived your luggage was waiting for you. I don’t know if the ground crew was far more efficient, or if the walk took longer than I remember.

New Orleans was an interesting airport. It had the New Orleans “Mardi Gras” look because the first time I was there it was afternoon of that Mardi Gras Tuesday. I remember calling my office (using a pay phone and telephone credit card) to say I was at the airport and was told very forcefully to make sure I got on the plane (it was the last flight out that day). Corporate travel (with whom I always made friends at every job), told the department secretary to tell me that if I missed the plane, the closest hotel room they could find was over 100 miles away – so make sure I got on the plane.

The Midwest:

In Chicago there are two airports. O’Hare was the big one and the one into which I mostly flew. I did use United a lot, and they had two concourses connected by an underground walkway. I remember it was an almost psychedelic experience because it was lit by a ceiling full of multi-color neon lights, and there was an ethereal, almost science fiction alien music being played as you walked (actually you did not walk, it was a moving walkway). Midway was a smaller airport (with lots of history) and was just being brought back into mainline service. O’Hare was further out and Midway was in the middle of the city, but I recall the taxi rides were similar in cost and time to the office.

Denver Stapleton was an older airport being replaced by a much larger new one (DIA) much further out. Like any major construction projects there were delays after delays in completion. When it finally opened I booked a business trip to the west coast with a Denver connection that had a three hour time interval between flights. I was able to visit all the terminals and see the new airport that day and continue my journey arriving maybe an hour after I would have if I booked the normal flights. I often changed planes at DIA and was amazed that even in the snow (enough snow that I would think it would shut down or greatly delay NY airports) things went on as if it was bright and sunny out. My flights that I was sure would be delayed due to snow went out on time.

The West:

When you land in Las Vegas you are greeted with a large open area by the gates that has a large bank of slot machines, and people (at all times of day) playing the slots. I must admit I am not a gambler, and all of my visits were due to visiting trade shows. The biggest ones were Comdex (a computer trade show) and CES (Consumer Electronics). In both cases (in those trade shows heydays) there were over 100,000 attendees and hotel space was at a premium. So were cabs. When you wheeled your checked luggage (or your carry-on) to the taxi loading area, there was a queue of hundreds of people waiting for a cab. It was very efficient because when you finally got to the front of the line the dispatcher had about 20-30 “slots” they would assign you one. The cabs would then come up and load whoever was waiting in the slots (for trade shows it was usually one person unless colleagues going to the same hotel wanted to share a cab). Considering the crowds, it was a very efficient system and it normally took you only about 30 minutes to get into a cab. They told us the city imported hundreds of cabs and drivers during the times of these shows.

LAX (Los Angeles) was the major airport for the area. Landing there you often could see aircraft landing on parallel runways as you were landing. The thing I remember most of the airport was the restaurant (Currently called Encounter) that is the space age shaped icon that is the main symbol of the airport in most all photos. When I was visiting it had a very Star Trek motif. Besides a nice meal (overlooking the airport) while visiting, I also used the restaurant as a meeting place to interview potential employees. You never had to explain twice where you were meeting them.

In the days before 9/11 security restrictions on terminal airside access I would also use meeting rooms at the Ionosphere Club (Eastern), President’s Club (Continental) or the Red Carpet Club (United) as a great places for potential employee interviews. I could fly into an airport, do 2 or 3 interviews, then fly back and never leave the airport. The cost for renting the meeting room was less than a taxi ride into the city.

SNA—John Wayne Airport was a nice alternative to LAX if you were going South of Los Angles. It was a convenient terminal (before it started growing, car rental was a convenient elevator trip down to a basement level.) My favorite memory was takeoffs. SNA is the middle of a highly populated area so there was a noise abatement takeoff requirement. The pilot would rev up the engines with the brakes on, release the brakes and you barrel down the runway, to a very steep take off, then the pilot dramatically reduced power and you quietly flew at a couple of thousand feet for a few minutes until you got over the ocean where the pilot could increase engine power to resume the take off and start to accelerate and climb.

Long Beach was a cute little airport that looked like a movie set from the 1940’s. But it worked very well (at least going to a hub for a connection, not a trans-con flight) and the thing I remember was it was maybe a 5 minute walk from the gate to outside the terminal and the car rentals were right in front of you in the parking lot.

Going to the Bay Area you had a choice of SFO, Oakland or San Jose. But SFO was by far the busiest. Before they built the consolidated car rental terminal, you took a bus that brought you to the various car lots. It also brought visitors to a Hilton hotel on the airport grounds, and I remember one bus ride where passengers just boarding the bus said they had to go to the hotel, but the driver had to tell them that hotel had been torn down a few months before. He suggested they should go back in the terminal and call their travel agent to find out where their reservation was now going to be honored. My memory of Oakland was an early business trip where I had a business meeting in Oakland that ran long. I mentioned I may not make my SFO flight since that was an hour away. They said “give me your ticket and let us check” and 10 minutes later they had me rebooked (making the same hub connection back to Newark) from Oakland—a 10 minute drive from their office. San Jose Airport had a special memory. I was waiting at the gate on a flight delay. By chance (to kill time) I called a former boss to congratulate him because he had started a new job with a new company. Over the phone he offered me a job—which I did accept the next day!

Honolulu and the Hawaiian Islands I first visited with my wife on vacation. We had a 9 day, 3 island “Pleasant Hawaiian Holidays with American Express” package. I remember we did as much packing and airport travel as we did sightseeing, but Hawaii is beautiful. In those days (1982) you showed up at the Hawaiian Airlines counter, and were given a seat on the next available flight (they ran at least every hour). Your luggage went on the next plane out (not necessarily yours) because I recall landing at each island, and all the luggage was already on the tarmac awaiting the tourists to pick them up and go to the car rental counters. One thing I recall is we had travel vouchers not airline tickets and turned them in for every flight (as we did for car rentals and hotels).

International:

Orly in Paris and Gatwick in London were, at the times I traveled, secondary airports and as such were not very crowded. Since my only need for the airport was the airplane and the taxi, that was no problem. I am sorry I do not have more memories of the airports themselves.

Luton Airport is about an hour outside of London and was the airport nearest to the office of a company for which I worked. I flew from Luton to Hanover Germany on a charter for a trade show. The thing I remember most what that at Luton there was no permanent signage for each airline. Large video screens would light up at each gate with the airline logo and name and the flight number. It seemed like a nice way for an airport to more efficiently use gate space and not leave gates unused for hours at time.

I visited Melbourne flying Continental DC-10’s. The 20+ hour trip started in LAX, we flew to Honolulu, deplaned (although it was after midnight the President’s club was open) then re-boarded (a different aircraft but same flight number) to Auckland New Zealand, where we deplaned (but did not go out of arrival security) then re-boarded to go to Melbourne. (Nice pick up of miles as well as a lot of fun). The return (because I think Continental only had one or two flights a day), you had a location to wait near the gate area, then they brought out pedestals and signs, and in about 10 minutes had a very professional looking check in and gate set up. The return home flights had the same routing in reverse order.

I was able to visit Moscow managing our company’s sponsored trade show. I did fulfill a longtime ambition of departing from the famous JFK Pan Am Worldport terminal. This was 1990 and a very strange and exciting time to visit the USSR. (I was there the week Mikhail Gorbachev won the Nobel Peace Prize). Arriving at Sheremetyevo Airport you went into a room the size of phone booth to show your passport and visa to a uniformed guard thru a window. On the return journey I got to the airport three hours early. Which was good because there was no such thing as a line. Everyone was pushing in a group to get thru security (which I was told was less for checking for guns than for people trying to smuggle out artifacts). I made it thru with maybe only 25 minutes before my Pan Am flight. I saw a Duty Free shop and wanted to get two bottles of Stolichnaya Vodka to bring home. I got them, and brought them on the 747 (upper deck on a 747-100 on Pan Am had chair side storage bins). I then carefully carried the glass bottles thru the NYC Pan Am Worldport and thru customs and brought them home. Just to find out how much I saved, the next day I went to the local liquor store – the identical bottles, bottled in USSR, were 50 cents cheaper in NJ!. So much for Duty Free Shops.

I hope these memories either brought a smile to your face or brought back similar memories of travel experiences you had in the past.

I must admit I was not into photographing airports (and especially on business trips since there were no such things as cell phone cameras) so other than a few photos from the Aviation Hall of Fame of New Jersey collection, I have no photos to share. Looking on the web for public domain or royalty free photos did find some of the airports, but the images are from today, not the terminals of thirty or more years ago. But hopefully you have some images in your own memory that will serve you in remembering.

All photography from From Wikimedia Commons.