Musings from a Passenger’s Seat: Pleasant Memories ~ Flight Segment 1

Written by Lester Anderson

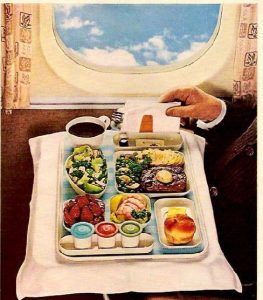

Over the years, I have flown 1.7 Million miles as a passenger (I state this both by my rough estimate and the fact that major airlines do keep and disclose these statistics to their frequent flyers). Fortunately I have no “horror stories” in that time. I have had my share of missed approaches; a few emergency landings being greeted by airport fire/rescue trucks; cancelled flights; missed connections; and trays full of both good meals and absolutely terrible meals served on board.

Shea Oakley asked me to write two articles, for Captain’s Log, and I thought the most appropriate thing I could do, considering the title of these articles, is to relate some experiences I had traveling those miles over 50+ years. I do not represent them to be significant (or even typical) but they are all memories that bring me back to a pleasant past.

The Changes in Air Travel

Air travel has certainly changed in these years. Probably the most notable thing that everyone experiences is that in the 1980’s and 1990’s the load factors were typically in the 70%-75% range. Not as good for the airlines as today’s almost fully booked airplanes, but more pleasant for the passengers—you often had an empty seat next to you. As a business traveler, I used to book a late flight returning home, knowing that if I was done early with my meeting, I could go to the airport and stand by for an earlier flight (at no additional cost), and usually get on the aircraft, and get a window seat. When American Airlines first introduced its frequent flyer program, they promoted that, as a frequent flyer, if you booked a window or aisle, they would put a hold on the center seat, and only use it if needed. The seating chart on the screen showed an asterisk in that seat indicating it was not occupied but only assigned if needed.

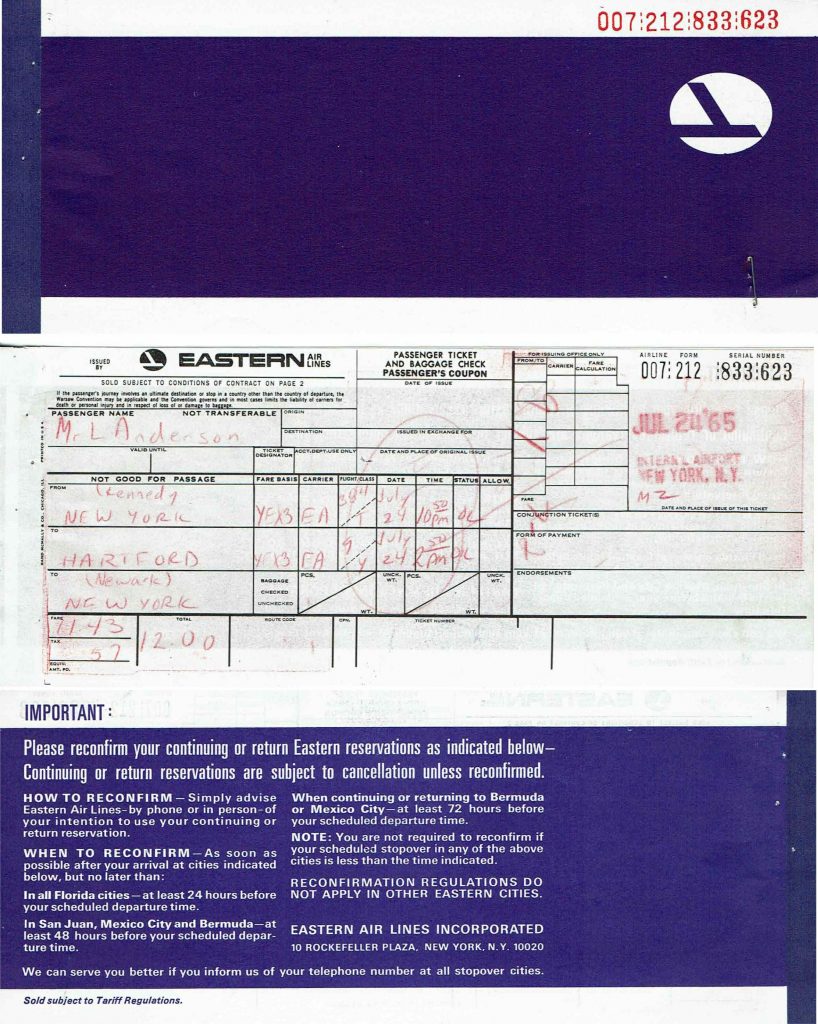

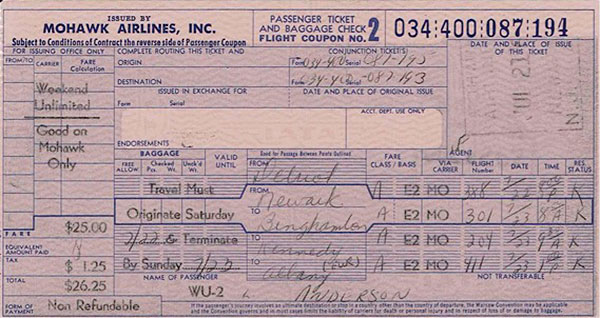

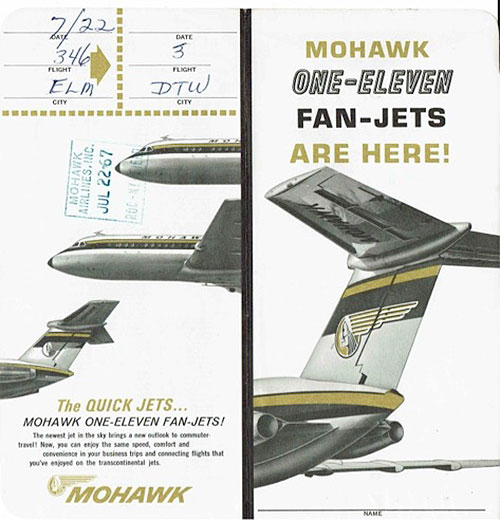

I was also a proponent of airline clubs. I lucked out early on with a membership in the Eastern Ionosphere club. I signed up for a $25 one-year membership. A few months later I was offered a 5-year membership for an additional $100 (which I took), and a few months later, I was offered and took a lifetime membership for an additional $250. Best investment I ever made because it then evolved into a lifetime membership in Continental’s President’s Club and now I am a lifetime member of the United Club. And this all started when I was a teacher and only flew once or twice a year to visit relatives in Orlando, Florida. When I left teaching and went to the corporate world, that membership became vastly more valuable. I also paid yearly fees to join Delta’s Sky Club, and before the merger I was a paid United Red Carpet Club member. Yes, the quiet surroundings and lounge chairs, and the often-free liquor were benefits, but the main reason—whenever you had a problem, the airline club helped. If a flight was cancelled or you needed to change a flight, you go into the club and there is no (or a short) line. And if you travel often, and they recognize you (and they did) you might even be treated into an upgrade (this was before the days when the computer automatically assigned them).

I was once on a Friday afternoon flight from Atlanta to Newark. Forecast was for snow to start in the late afternoon in the NY area. My 2:00 pulled back from the gate, and maybe we got 20 feet, when the aircraft stopped, and the pilot came on the intercom to give us the bad news that Newark closed due to snow. We all went back out to be reticketed. I was about 4th in line and they were trying to get people to the northeast. Hartford was open but was anticipated to close very soon. Same thing for Boston. I got to the front of the line and said “book me to Orlando” ( I have relatives there). They told me that was the opposite direction. I said, “but it’s not snowing there” and I got a round of applause from the rest of the line. And in those days interline ticketing was normal. Delta booked me on an Eastern L-1011 to Orlando on a flight leaving within the hour and an “open ticket” back to Newark when things cleared up (Sunday). Today, I am afraid I might be waiting in Atlanta for a few days just to find a flight with an open seat.

Be kind to your fellow passengers

I love to fly, and I am not ashamed to tell anyone that. But not everyone is, and sometimes my seatmate was not happy being on an airplane.

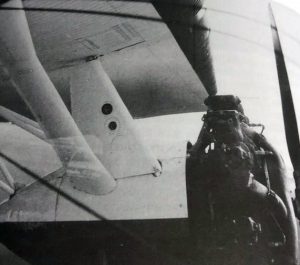

In the late 1970’s I was on a National DC-10 coming home from Florida. The DC-10 was a great airplane, and like all widebody planes it was “different” from the single aisle airplanes in that the cabin was divided into smaller sections. Reading up on everything I could find about airplanes, I learned that the cabin dividing walls were attached to the floor and would “float” on the ceiling so that as the aircraft cabin twisted (a normal situation in aircraft design) you might see the top of the walls move independently of the ceiling.

This flight was a very bumpy one. I would not call it severe turbulence, but enough that all meal service and walking around the cabin was stopped. The woman next to me (maybe my mother’s age) was afraid of flying. As we were bouncing around, she was upset, and I was talking to her explaining that is was nothing to be afraid of, that airplanes were built for this, that the captain was on the radio to see what altitudes had less turbulence, and that as soon as the captain could find smoother air I was sure he would get us a better ride. While I am talking to her calmly and trying to minimize her fear, I am watching the airplane twist and seeing the wall cabin barriers move what looked like 6 inches each way from their parked location on the ceiling. That excited me that I was actually seeing this, but I could obviously not say anything or even make reference to my excitement in seeing this engineering marvel as I was trying to calm down my seatmate.

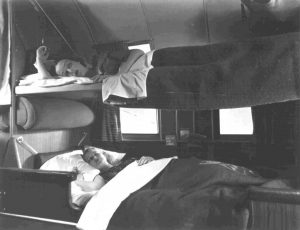

In the late 1980’s I was on a United 747, upper cabin (my favorite place to be on a flight). I was traveling on business and sat next to someone a dozen years younger than I was. He was deathly afraid of flying. He had just started a job with one of the big-eight accounting firms as a consultant, would be traveling a great deal, and was very concerned. I took most of the rest of the flight trying to first explain the wonders of air travel and why he should not be afraid, and then explaining some tips I know from co-workers who didn’t like flying as to how to minimize their fear. On a 747 walking around is easy (especially in First) so a couple of times I told him that we should walk down to the lower deck First cabin to “stretch our legs”. He was concerned about long taxi times, and I gave him the simple trick of booking an early flight out. We went over the usual things they tell you (drink lots of water, little coffee, and almost no liquor) and to stay in shape for business meetings when you land. It was a coast to coast flight, so we spoke on and off for over 4 hours. At the end of the flight he thanked me and said he felt much more equipped to perform the duties of his new job—at least the part about flying to the client’s location.

I was on a US Air flight (I think from Charlotte) and we were on the airplane because of a weather delay in Newark. It was a few hours and because we could be given clearance to take off at any time, passengers could remain on the aircraft or go out to the gate are but were asked to stay close by. There was a passenger seated next to me who kept complaining about US Air and the delay. I finally suggested that if US Air could control the weather, they could make a lot more money doing that instead of sending people around the country in aluminum tubes. (By the way, he later got off and either found another flight or decided not to go, because he did not come back). Later the pilot came back to chat. Since it was a few hours delay (and I know about crew schedule times), I asked the odds of our taking off tonight. He said that the crew had plenty of time and that was not a concern. He was honest in saying that US Air would certainly like to get us to Newark as ticketed, but they were probably even more interested in getting the aircraft there for the early morning flights.

I travel much less now, and being retired, never for business. Add to that the hub/spoke system of airline scheduling and connecting no longer has to be “the only way” to get there. But in those days, when flights were delayed, one of the things I felt good about, both from the airline personnel who announced it, and from fellow passengers who allowed it, was the announcement that a number of travelers had close connections and if you were not in that situation, please let them exit first to make those connections. Both on the flights where I needed to rush out to connect and on flights where I waited because I was not in a rush I saw probably the best example of human teamwork and kindness to other fellow travelers anyone could experience.

International

Traveling on business I did my share of international travel. I went to the places many people go, Paris (truly the most beautiful city), London (a lot smaller than you think or expect), Melbourne Australia (a place that prides itself on being the most like the US—and if only it were closer I would go back) and of course Canada (which was easy because passport control and customs were on the Canada airport side, so on return you just got off the airplane).

Probably the most memorable trip was a Pan Am 747 from Kennedy to Moscow for a trade show my company was conducting there in 1991. The flight was great (I was on the upper deck) and efficient. Moscow was an interesting place. In those days (early 1990s) you only went to places where you could spend hard currency (not Rubles). I saw a lot (we all took a little time to be tourists) and the things I remember:

Children are the same all over the world. They will play and climb over monuments or memorial cannons in parks.

Young men are, too. I saw many soldiers in uniforms at the end of the day carrying one rose or a small bunch of roses to their wives or girlfriends.

Fresh fruit and tomatoes (technically a fruit but you know what I mean) at every meal—even in November.

And in my limited experience no one in Moscow knew how to make a good cup of coffee (but the tea was plentiful and good).

There are no “lines” at the airport. It is a mad dash of pushing. It took me 2 ½ hours to get into the gate area and be able to board the return flight with just 20 minutes to spare.

Because you don’t drink the tap water (or even brush teeth with it), everyone uses bottled water in Moscow, but even that safer water tasted salty. I think Pan Am gave everyone large tumblers of water when they sat down and asked for a drink from the flight attendants.

Lester Anderson

If you have enjoyed my ramblings, this article will continue in the near future. There will be more random experiences I remember fondly, and one of the ways I got to learn some fascinating facts about different airplanes.