1980s,Bandeirante,Dolphin Airlines,Dolphin Airways,EMB-110,Embraer,Florida,regional airline

TURBOPROPS, ROUND FOUR: Dolphin Airways

By Ellis M. Chernoff

Dolphin Tails, Part One

Toward the end of 1981, I found myself in the office of the Director of Operations for a soon-to-be-start-up airline called Dolphin Airways. The appointment had been made for me, but I was interested in the new firm as they planned to launch a regional business-oriented scheduled service in Florida and adjacent states with a new fleet of Fokker F-28 jet airliners. In fact, the D.O. had an artist’s rendering of one of these to-be-delivered jets in Dolphin livery on the office wall. While I expected to interview for an initial cadre captain position, I soon learned their plans had changed. Rather than starting a fleet of regional jet airliners, they instead ordered the Embraer EMB-110P1 Bandeirante.

The two aircraft are quite different: a 65-seat turbojet airliner versus an 18-passenger turboprop. I was obviously surprised. The answer to my question was that they were unable to obtain the needed financing for the new jets. In fact, the startup firm’s financing was novel and somewhat absurd.

The principals would form Master Limited Partnerships to finance each separate aircraft acquisition. Two aircraft were already being prepared for delivery in Brazil. My response was that the Bandeirante was not a good choice, even for an 18-passenger commuter plane, especially compared to the Swearingen Metroliner, an aircraft I had been operating for three years.

The Metro was considerably faster, pressurized, and burned fuel at the same rate, which meant lower fuel costs for a given city pair. The 50 knots speed difference also translated to more revenue seats available per day than the slower option. The Metro also had single seats on each side of the aisle rather than the cramped double seat in the Bandit.

The D.O responded, “Who needs pressurization in Florida? There aren’t any mountains.” My

reply was that the puffy clouds over Florida might as well be mountains. Flying at altitude would provide a smoother ride, and the plane could descend fast in terminal areas, which would be painful in an unpressurized cabin.

Well, they had made up their minds purely based on the Brazilian plane’s lower cost. Despite arguing over aircraft practicalities, I was offered a captain slot in the first class of new hires.

Ground school commenced in-house and before any planes had been delivered. Once an aircraft had

arrived, I received some flight training in it. The first two ships were limited to a maximum weight

of 12,500 lbs, just as the Metroliners I had been flying. Their PT6-34 engines were 750 HP (less than the TPE-331), but with a fat wing, the plane performed well. Surprisingly, it handled even better than the Metro on a single engine. The free turbine PT-6 was reliable and easy to start, even on battery power alone. The planes were brand new with good avionics and a well-laid-out cockpit. Subsequently delivered examples were certified at 5900 KG/ 13007 lbs, which required a type rating for all captains.

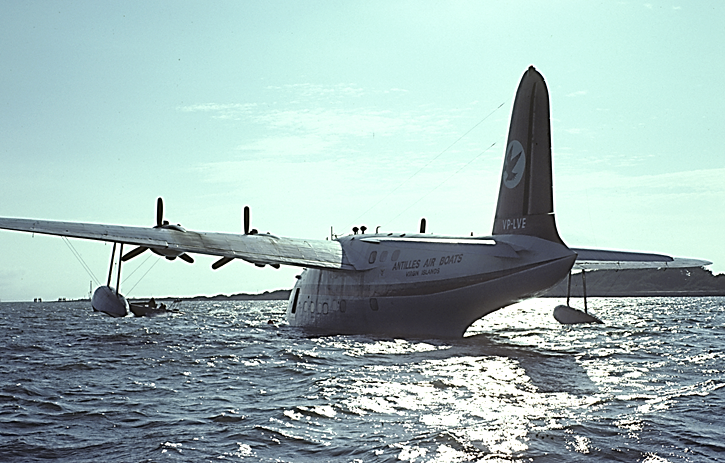

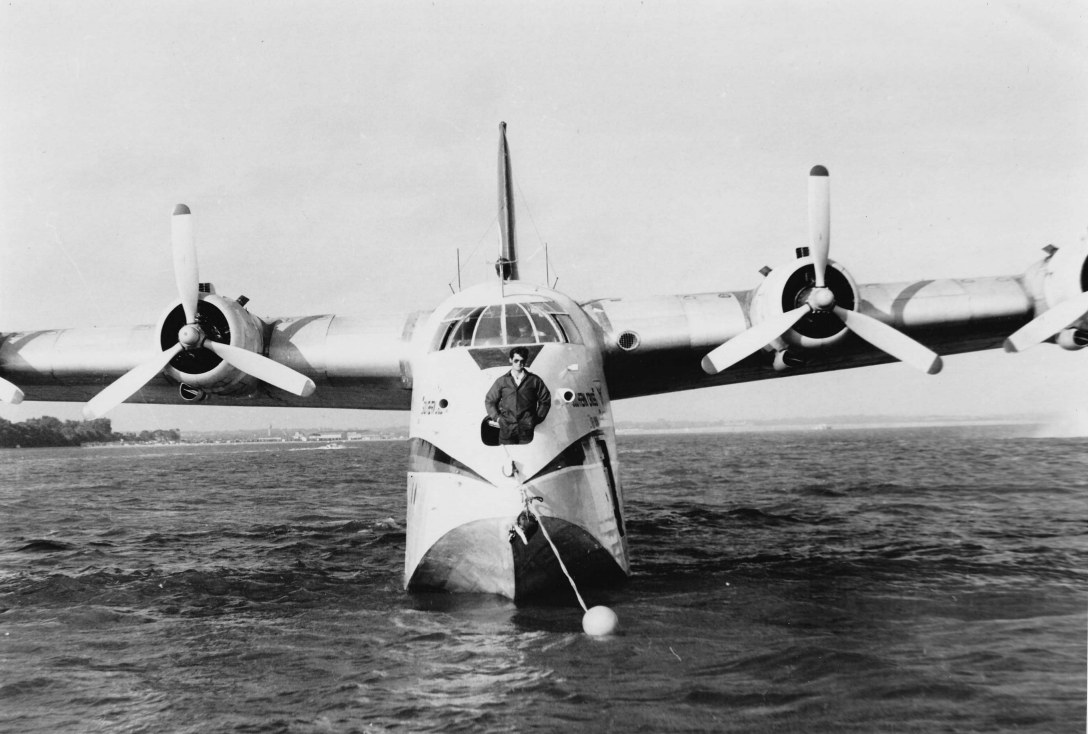

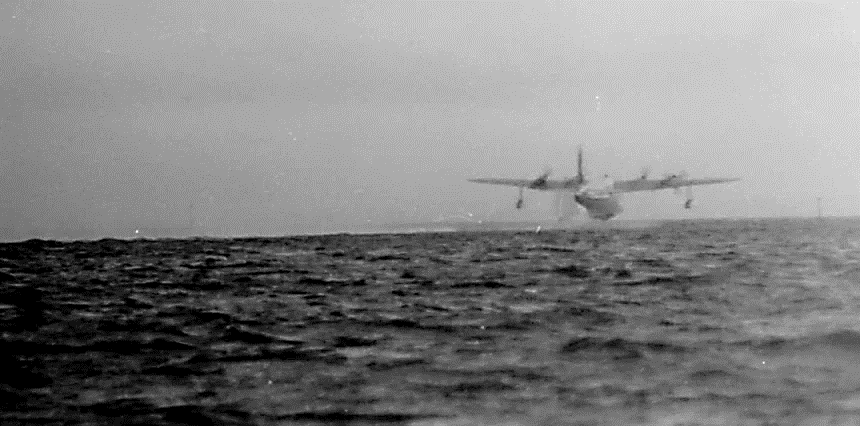

Photo by Ellis M. Chernoff.

As the startup date for the airline was quickly approaching, management realized we had more

captains than were needed for the small initial fleet. Due to my substantial regional operations experience, I was asked to take on flight following until we could hire and train full-time employees for this function. As part of this preparation, I also developed some standard loading profiles to simplify weight and balance as well as a route book that would provide a quick reference for each scheduled city pair, the normal fuel burn, alternates, and the additional time and fuel when needed, and other information to adjust for wind and temperature variations. I performed all of these calculations longhand with a calculator and legal pads. At the time, personal computers were still rare and there were no online services or apps for flight planning.

Our airline would be operating under FAR 135, which did not require a dispatcher, and each pilot was responsible for determining compliance with fuel requirements and pre-departure review of weather and other matters. But as a convenient tool and aid to the pilots, this printed guide was carried in each plane. I also used it as I assisted with flight planning as we began scheduled operations. One of the other people involved as an initial pilot owned both a home computer and a printer (dot matrix) and assisted me in reducing my hand-done calculations to print.

On the first day of scheduled operations, all flights originated from Tampa International Airport (TPA). As

the principal flight follower, I was equipped with pads of paper, a long table, and a multi-line

business telephone. My list of the day’s flights included the crew names and the aircraft assigned to each flight. I started early, calling flight service to obtain all the weather information each crew would need, and then I calculated their initial fuel loads and where downline they would refuel. By the time each crew arrived, I had a briefing sheet and had filed their flight plans by telephone.

As you can imagine, this job was hell on the first day. Each station and each executive kept calling

me for the status of every aircraft and flight. I could hardly prepare for the next flights, while constantly

being interrupted by phone inquiries. Finally, put a stop to those interruptions by insisting I would call

if there was a problem. Thankfully, soon full-time staff were hired and trained, and I could finally

go fly the line.

Photo by Ellis M. Chernoff.

The passengers were not too impressed with this commuter plane. Dolphin Airways was advertised as “a business person’s airline.” We served Tallahassee, Florida’s capital, as well as Tampa, Jacksonville, Orlando, Fort Lauderdale, West Palm Beach, Panama City, and Pensacola. Service extended to Savannah and New Orleans.

The narrow double seats made for uncomfortably close contact of two adults, and the cabin ventilation system was either too hot or too cold. In fact, ice pellets would spit out of the air outlets and hit the passengers on the head. Sometimes the main duct would become detached in the tail section, and no air would come through at all. Cabin temperature was controlled by a toggle switch on the co-pilot side, but there was no position indicator or temperature gauge for the air in the distribution ducts, so it was a bit of guesswork and required finesse.

As in all turboprop aircraft, the cabin was noisy. Being unpressurized, passengers often had a bumpy ride in the warm thermals of Florida. Flying at higher altitudes might have provided a smoother ride, but our lack of pressurization or supplemental oxygen limited how high we could fly. Pilots had to descend at about 500 feet per minute to minimize passenger ear and sinus discomfort. The outstanding pressurization system of my trusty old Metroliners allowed routine descents at 1500-3000 feet per minute. The slow descents we had to fly for Dolphin were a challenge to mix with the traffic at the busy airports.

Tallahassee, FL, in January 1984. Photo by Ellis M. Chernoff.

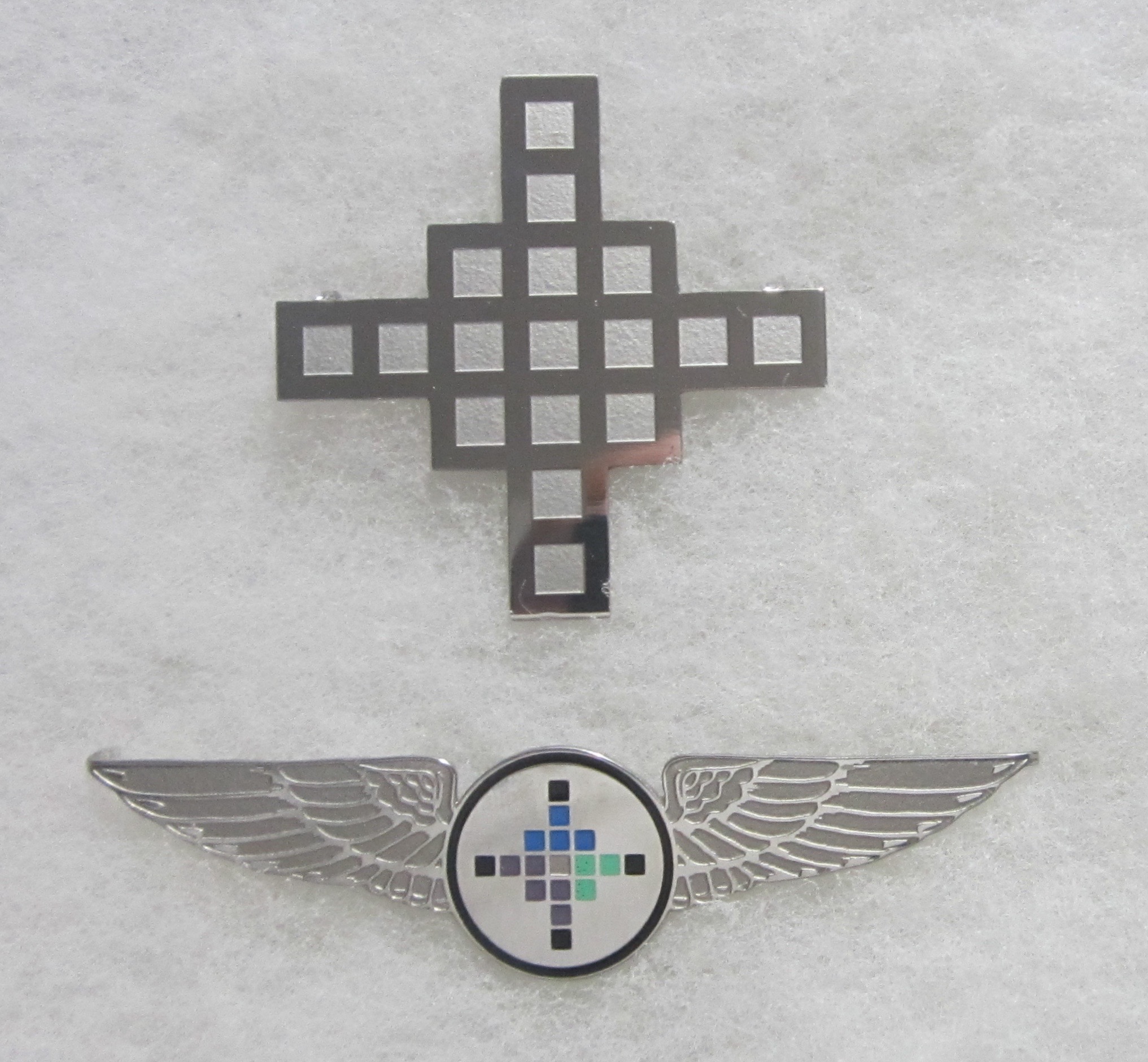

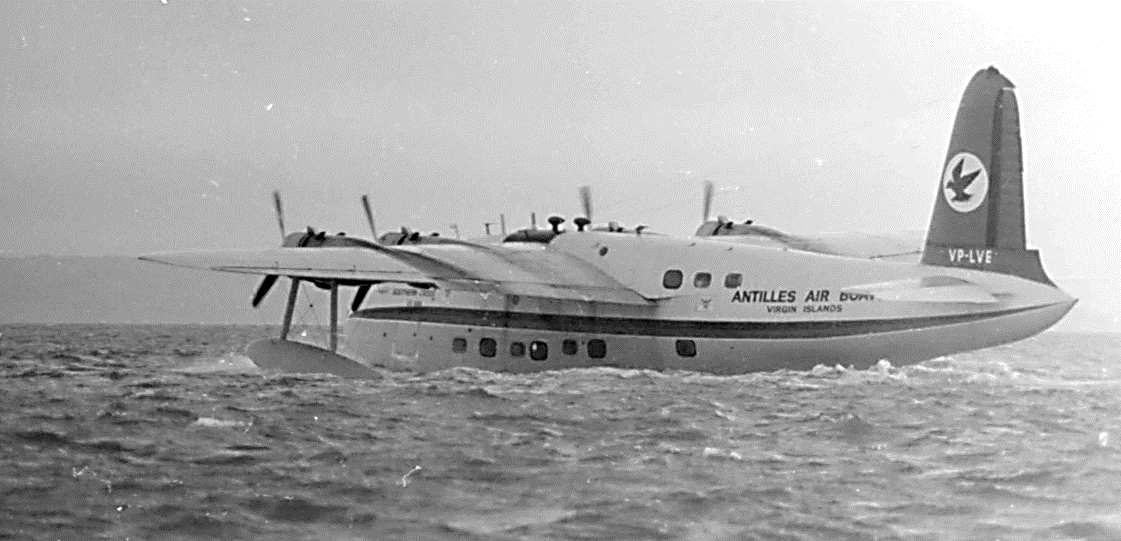

Dan Gradwohl collection.

After some time, we had acquired a good-sized fleet of aircraft, and the company name changed from Dolphin Airways to Dolphin Airlines. But, executive management abandoned the airline, and for many months, we were an airline operating with only an operations department, maintenance, and little else. In this state, the pipeline of willing investors for limited partnerships soon dried up, and the next set of new aircraft could not be delivered.

To be continued . . .