1950s,Catalina,Garuda,GIA,Indonesia,PBY-5A

My Catalina Story

By Arthur Smit-Roeters

What it was like to fly on board a Catalina in the early 1950s in Indonesia

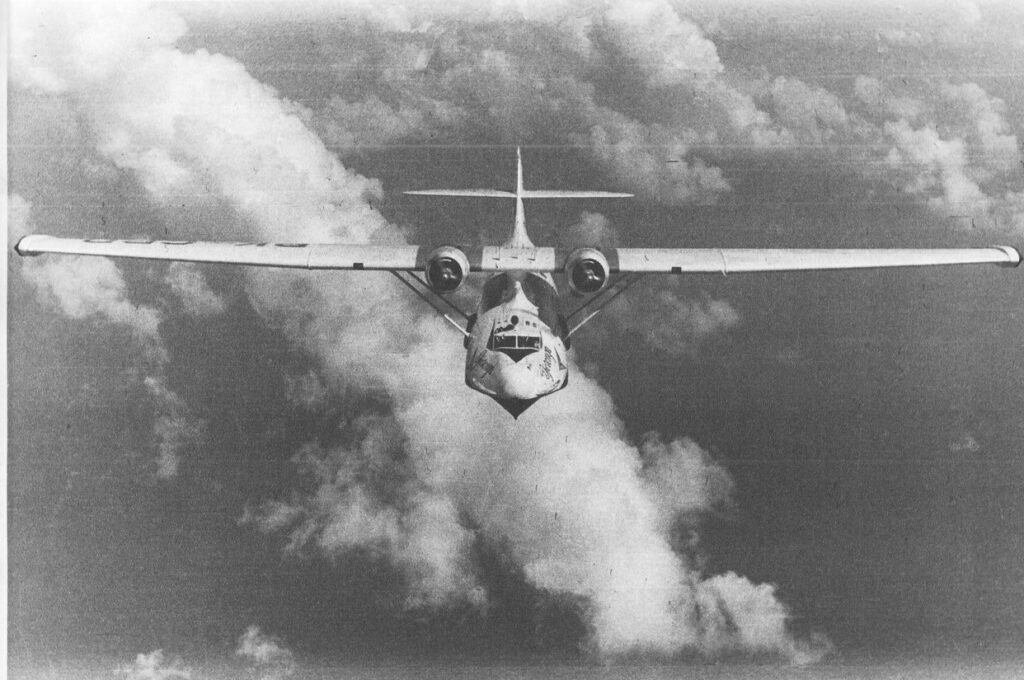

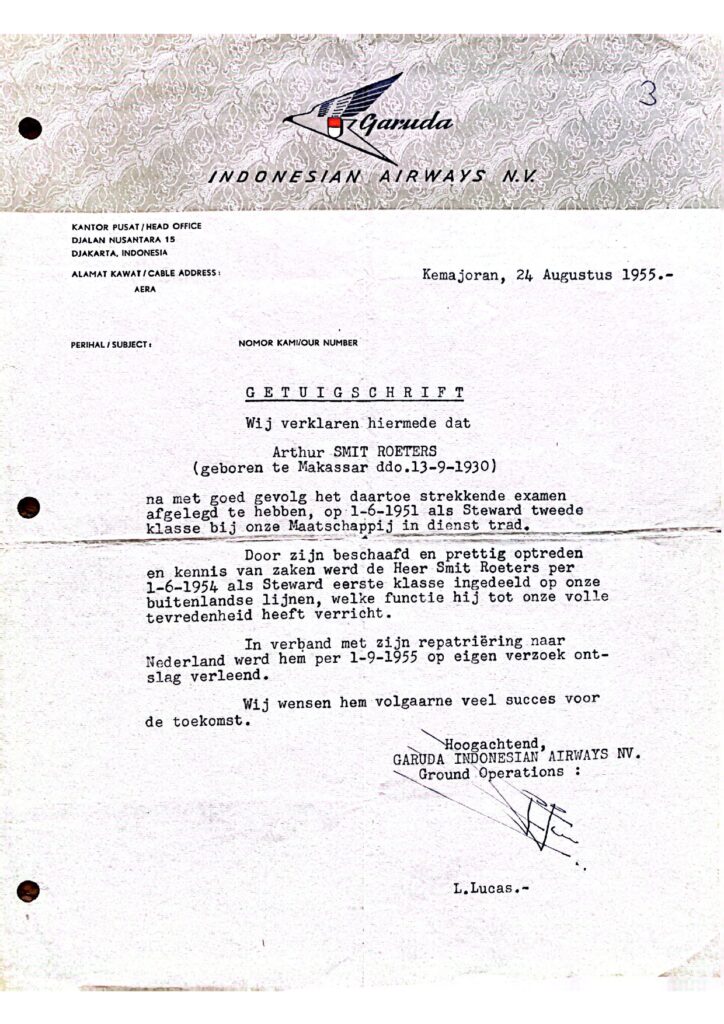

Recently, a good friend presented me with a fantastic book: 80 Years, A Tribute to the PBY Catalina, authored by Hans Wiesman. Some of my flying time in the 1950s with the national airline of Indonesia, Garuda Indonesian Airways (GIA), was being in the air as a steward on a PBY-5A Catalina amphibian flying boat, a period of pioneering. I remember being accepted for training after passing some tests and I was ready to make my first trip after about three weeks of classes. One of my first flights was on board a Catalina flying boat, an ex-WWII long-range patrol seaplane converted into one carrying 16 passengers. Long-forgotten images pop up in my mind.

The front office or cockpit was not my realm. Before today’s glass cockpits became the norm, in my days they had “steam gauges.” I flew on board a “steam gauge” airplane. A somewhat condescending term used to indicate a plane is equipped with old-fashioned and almost obsolete instruments. The electronic Flight Management System now commonplace had not appeared in anybody’s dream. The pilots were it. Navigation was by dead-reckoning and a simple Radio Direction Finder (RDF) was an essential piece of equipment. Yes, it was all manual labor. For me, 88 years old in 2018, it’s unbelievable how things have changed.

What a Garuda amphibian PBY-5A looked like inside

My workspace, located between the cargo area in the tail and cockpit, consisted of two cramped compartments, each holding eight passengers. The wheel wells were located between them. One had to stoop through three hatches to get to the front passenger compartment from the cargo area where my rudimentary pantry was located. I could almost lean on the cargo in my back when I was facing the portside located pantry in front of me. I had to stoop through another hatch, the fourth one, to get to the pilots.

Each passenger had access to a life preserver. There were no emergency exits. An inflatable life raft was not part of the inventory. The lavatory was just a bucket covered by a seat and located in the tail section. Space was very limited and one could not stand straight up.

The only thing I didn’t like during my flying time was the smell of even an empty airsickness bag that was made of asphalt tar-impregnated paper. The smell induced the user to have a quicker barf time. Since the plane was not pressurized, we could not fly over the weather. Turbulence made this bag a popular item for an airsick passenger.

The inside of the plane was a bare-bones affair. Only the two cabins had a fuselage covering, the rest of the plane inside was just aluminum skin painted chromate green. There were no reading lights or airvents over the non-adjustable passenger seats. No night flights were scheduled, but there were delayed flights with arrival times past sundown. A sunken aisle divided each eight-passenger compartment along the keel into four seats on either side. Passengers faced each other. When two people sitting opposite each other wanted to stretch their legs they had to first figure out where to place their feet.

My guests had to board via a door with a high threshold where the port-side gun position was located in the war years. Thus, stairs with a lot of steps had to be rolled up to the side for entry or a bobbing launch when on water. After the first obstacle, the passenger had to crawl through the hatches in the bulkheads to get to the front cabin. There were no overhead bins and suitcases of all sizes had to stay in the cargo area, the space where once the two gun positions (blisters) were formerly located. Carry-ons as we know them today didn’t exist.

Getting aloft

Prior to getting aloft, I had to make sure everybody was strapped in. The sounds and sights of a Catalina flying boat takeoff from the water were always spectacular.

Before the start of an engine, one could hear the groaning and clanking valves as the propeller was rotated through nine or more blades with the ignition “off” to clear accumulated oil out of the bottom cylinders of the double-row, 14-cylinder engine. Then with ignition “on” the engine burped a few times before a smooth sound indicated all was going well.

After taking in the floating anchor and when the aircraft was lined up, takeoff power was applied and with the increasing speed, foam started to blow past the windows. The plane was about ready to leave the water when we could hear a sound like skimming over a gravel road under our keel, announcing the aircraft was hitting the top of the waves. With the two engines close overhead and no sound isolation, it was very noisy inside, but the auditory sensation of healthy engines was always music in my ears.

Aloft

As seen from the aircraft’s window the jungle below looked like an endless and dense cauliflower field with an occasional bare patch where natives had slash burned the area and planted their corn or cassava. The soil looked yellowish. It certainly was not loam. Over the years hardwood trees were able to survive and thrive with the help of the monsoon rains with precipitation of 120-145 inches a year in the lowlands. A downed airplane would disappear in the dense jungle foliage. It seemed all the water in rivers had a brownish color and crocodiles were ever-present.

With an average cruising speed of 108 knots, and being in the air for many hours, it was difficult to get out of one’s seat for some leg stretching, but some people did. The distance between Jakarta and Singapore is about 550+ miles. With a cruise speed of 108 knots per hour, the flight, with a stop in Billiton (Belitung), and a Singkep sea landing, made the flight an all-day affair. Logging 100 hours of flight time per month in PBY-5As, C-47s/DC-3s, and Convair 240/340s was almost normal for me.

Tasks on board

Once in the air, I doled out cold lemonade drinks, first to the cockpit crew since they were at their stations to do their checks long before the pax boarded. Then I went around with reading material including various magazines and newspapers. Safety cards? Are you kidding? On the Singapore flights, I had to help passengers with deciphering and filling out their customs and health forms printed in English. Inflight meals were very simple. No alcohol was served.

Flight impressions

I still remember landing on the river where the Dutch Bruynzeel lumber company had their sawmills at Sampit, a jungle outpost. The slow-moving river water had a brownish color due to suspended sawdust, tree saps, and rotting leaves. The employees were always happy to see the Catalina since we brought with us one or two tall wooden reinforced boxes filled with movie reels for their entertainment during the coming week.

Although a ground crew in their boat made sure that the landing surface was clear of obstacles, we always made a pass over the site, looking for submerged logs. We had no problems getting back in the air, but I remember there was a bend in the river at the end of the takeoff run. The tree-lined jungle river was wide enough for maneuvering when checking the magnetos of each 1200-horsepower P&W R-1830 before departing. It was great to look up at the tall trees on both sides of the “water runway” at the start and then feel how slowly but surely the big 104-foot span barn-door wing (it was not equipped with flaps) lifted us over the trees at a leisurely speed of 75 to 80 knots indicated air speed (KIAS) and then continued at a leisurely cruise speed of about 108 knots or about 124 mph.

All landings on smooth water were power landings. One time the captain allowed me up front to witness a stall landing, normally used when the waves were choppy. The airplane’s nose was up high and the rudder pedals were useless. The Dutch ex-Navy WWII cockpit crewmembers were excellent pilots and sailors.

I made many flights to Kallang Airport (Singapore), via Billiton (Belitung) Island and Singkep Bay where passengers were transported to and from the plane by a motor launch. On days when the sea had light swells, it was awkward to transfer some passengers between the up-and-down movements of the Catalina and the launch. It took some time for the landlubbers to deplane or board.

While waiting for the Singapore-bound passengers it became unbearably hot inside the plane. The crew, in various stages of undress, moved to the top of the wing. At one time the board engineer had to relieve himself and went to the end of the portside wing that had its wing float in the water. A devilish crewmember suggested that the rest of us run towards starboard at the “right” time and see if we could flip the engineer off the wing tip. Running towards the high starboard end, the portside float lost its suction, and the engineer, wearing only his briefs, lost his balance and tumbled into the sea. The few seagulls looking for handouts could not stand his loud and unhappy cursing and left.

Another time on short final to the steel-matted Billiton strip in bad weather, one of the engines acted up and the propeller had to be feathered. After circling the area at what seemed just above treetop level, the pilots spotted the strip, and then the remaining engine called it quits! The PBY became a big glider, which took up valuable runway space and thus overran the airstrip. No power meant losing hydraulic pressure in the lines and no brakes. We didn’t have to disembark in the mud since a truck picked us up. There was a light drizzle and our miserable bunch was taken to the terminal, a simple bamboo structure with a palm frond roof.

In the early 1950s, all countries along the western Pacific Ocean rim were still in the process of recovering from the devastation caused by the Japanese war machine. I remember many items were exorbitantly expensive if you could find them. This included nylon stockings, parachute nylon, yardage of nylon, yardage of silk, cigarettes like Lucky Strike and Chesterfield, Johnnie Walker Red or Black Label Scotch whiskey, oranges and apples imported from Europe, etc.

A few crewmembers thought they could make a quick buck, but since nobody was a professional smuggler, things didn’t turn out well. The customs people were smarter than the would-be smugglers.

I remember on a return trip from Singapore somebody was going to make a lot of money by illicitly importing a shipment of 144 cartons of Chesterfield cigarettes. The customs officials in Billiton got word about the attempt and the crew was warned about it while in flight. The response was quick and the big package was pushed out of the plane through the ventral gun hatch below in the tail. Some fishermen may have found lots of cigarettes, manna from Heaven, in their fishing nets,

Billiton customs always came on board to check for suspected contraband from Singapore. On a flight before me, they hit the jackpot. The Catalina had a wooden floor and when the law man picked up a loose string, he unknowingly untied a knot. A bundle of nylon burst out from under the floor. There was no owner who claimed this expensive shipment.

The crew always pulled jokes on each other. When the captain’s billfold, including passport and customs/health papers, landed on the floor under his seat, the front office staff decided to pull a good one on him. After landing in Singapore the Garuda representative was motioned to come up to the door. It was explained to him that after he received the captain’s belongings, he should move to a spot on the ramp below the portside cockpit window and then later get the attention of the man in the left seat. Then he would innocently explain that a plane before him had delivered his credentials. Our pilot in command was sweating bullets while he was crawling all over the cockpit to find his papers but was mighty happy that he got them back. Not having papers at an international airport meant problems galore. He was a good sport, but the rest of the crew knew revenge would be sweet.

I also remember flights from Jakarta to Pontianak via Billiton and landing on the wide Kapuas River in Borneo (Kalimantan). Once we were coming in (on the way to Pontianak) below treetop level to chase crocodiles sunning on mud banks alongside the river back into the water. It was no surprise to pull up and fly over a cargo ship that appeared in front of us. I was part of a crew on many Catalina flights to Balikpapan (a town dominated by a big oil refinery and oil tanks) routed via Banjarmasin (a major trading center). I had to give up my seat on the short ±75 mile flight from Balikpapan to Samarinda due to heavy passenger demand. There was room for only 16 people, eight per compartment. There was one compartment in front of the landing gear and one behind it. I had to stoop through hatches from the galley area to the cockpit with drinks and food. Those were the days. All the PBY pilots were easygoing and came from the Dutch Navy after WWII, which made them different from cockpit personnel manning other types of planes.

I accompanied President Sukarno on a charter trip through the Lesser Sunda Islands on board the Catalina “Enu.” On a second trip with the president, he addressed me by my first name. Wow, what an honor. The “Djoronga” was the second plane accompanying us on this trip. During one of the flights a crew member, I think it was our wireless operator, with a good Leica 35mm camera (extremely expensive in those days) took some unique shots of the other PBY flying in close formation below us, through the opened gun hatch below in the tail. See attached photo.

The Garuda Indonesian Airways Catalinas were all phased out in the mid-1950s.

Memories, just memories.

Photo courtesy of the Arthur Smit-Roeters Collection.

Article last revised on December 18, 2018.

Mr. Smit-Roeters Flew West on February 11, 2023. You can read his obituary by following this link.