TACAN,VOR,VOR-DME,VORTAC

VOR Chasing: My Unusual Hobby

By Phil Brooks

Being a Private Pilot and Aircraft Dispatcher for several decades, I’ve always been interested in various aspects of aerial navigation. In the mid-1990s, with GPS navigation on the horizon, I decided it was time to document the “brick and mortar” navaids. My favorite is the VOR station- that stands for very high frequency, omni-directional range.

These short-range navigation facilities exist worldwide, and were developed by the U.S. Civil Aeronautics Administration in the late 1930s, and perfected during WWII. These beacons transmit a signal in 360 directions (radials) over a VHF frequency, in the range of 108-117.95 MHz. Pilots tune in that frequency and the receiver in the aircraft directs them to fly to or from that VOR. It also allows them to identify and intercept certain radials, for en-route navigation (on so-called Victor Airways below 18,000 feet above mean sea level, or on Jet Routes, above Flight Level 180) as well as instrument approach procedures. The intersection of two radials, from two different VORs, can also allow one to determine their present position.

I concentrate on those in the United States, so this article will focus on those maintained by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), the successor to the CAA. There are other aviation navaids, but VORs are large, easily identifiable structures, so they caught my eye first.

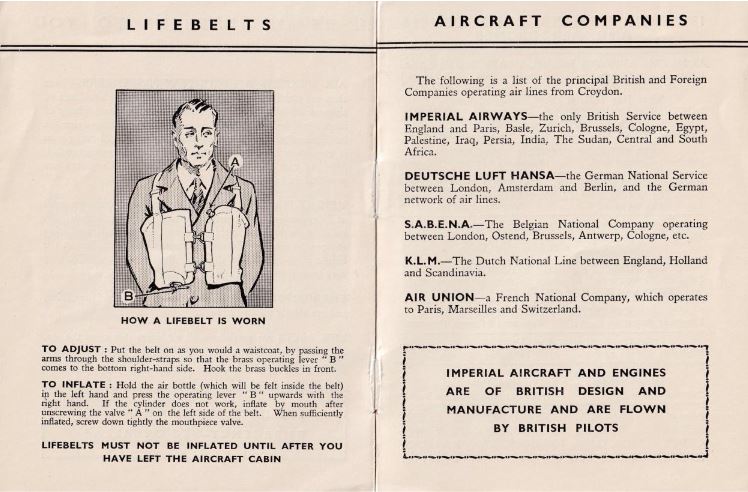

VORs basically come in two versions, one that looks sort of like a big bowling pin, and another, the Doppler variety, which is typically elevated above the surrounding terrain, when nearby structures might affect the signal, which is usable in “line of sight” only. Some are classified as VORTACs, because they have the military’s TACAN (Tactical Air Navigation) system built-in, which provides similar information. There are also VOR-DMEs, which provide distance to the station. More detailed information can be found on wikipedia.com. They can be identified in flight by the Morse code of their identifier, aurally broadcast on the same frequency.

Here is an example of the Doppler VOR:

October 2019

Photo Courtesy: Phil Brooks.

The technology, the world standard for more than 50 years, is still in use, but GPS (also known as GNSS-Global Navigation Satellite System) now dominates aerial navigation. The FAA is decommissioning most VORs over the next few years, but keeping what they call a Minimum Operational Network (MON), to provide basic conventional navigation service for operators to use if GNSS becomes unavailable.

The MON is intended to provide signal reception starting at above 5,000 feet Above Ground Level (AGL) over the continental United States, giving pilots the ability to navigate to a MON airport within 100 nautical miles and conduct an Instrument Approach without the use of GPS. This is planned to consist of 590 VORs, out of the almost 1,000 that existed in 2016, when de-commissioning began. So my hobby will continue for the indefinite future! While GPS is wonderful, it is vulnerable to some extent, and certainly has none of the “romance” or physical presence of the VOR system. Perhaps when the last VOR is de-commissioned, that will be my time to retire!

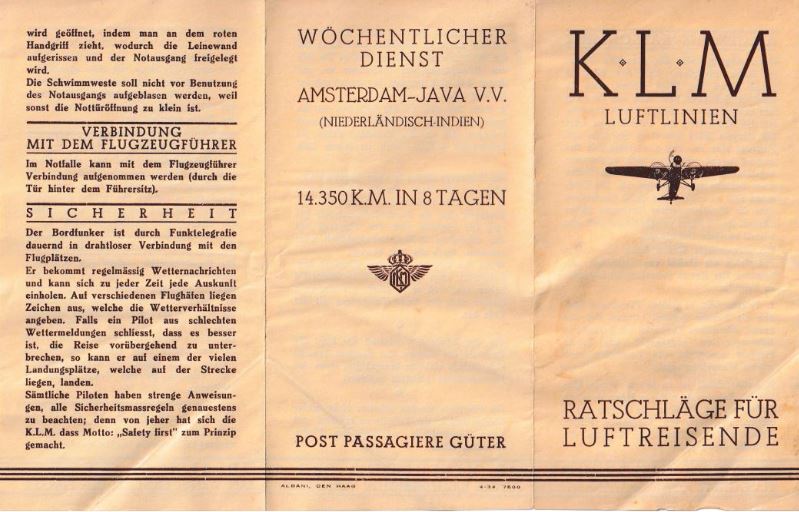

I appreciate both the history of the VOR system, because it was such an improvement over earlier systems of navigation, and, as a student of geography. My favorite VOR is the one nearest to my home, Brickyard (identifier: VHP), near Indianapolis, IN. I have dragged my wife Pam, even when we were dating, to a number of VORs, and she has a favorite too-Dove Creek (DVC) in southwest Colorado.

Photo Courtesy: Phil Brooks

The first VOR in the U.S. was located at the Indianapolis municipal airport, now Indianapolis International (IND). This was the location of the CAA’s Technical Center at the time. Indianapolis VOR was moved about 7 miles northwest of the airport at some point, and the name was later changed from Indianapolis (IND) to Brickyard (a nickname for the nearby Indianapolis Motor Speedway) in the 1990s, to avoid confusion between the VOR and the airport, since they were no longer co-located.

They are mostly named for nearby towns or cities, but sometimes after people. They also have three-letter codes, like airports. Some unusual names are Crazy Woman (CZI) in Wyoming, and Gipper (GIJ) near South Bend, IN and Notre Dame University.

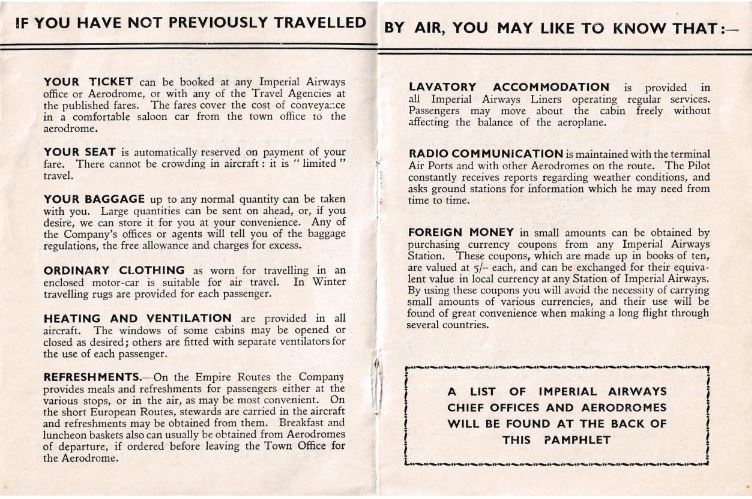

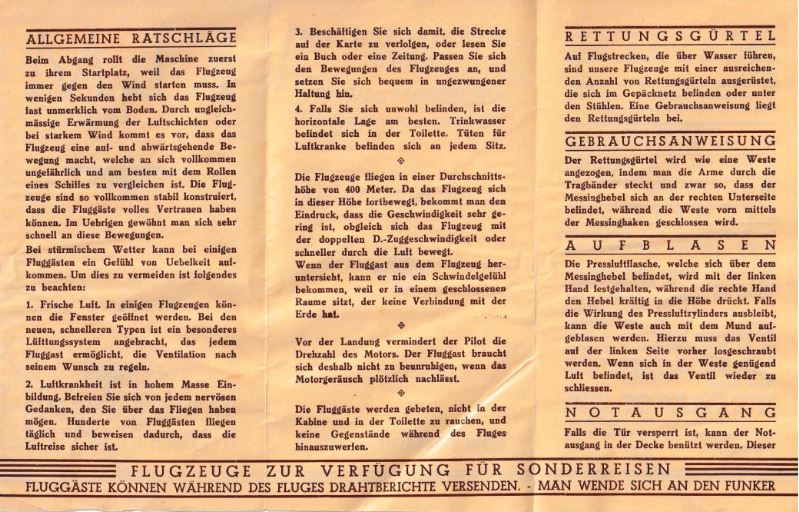

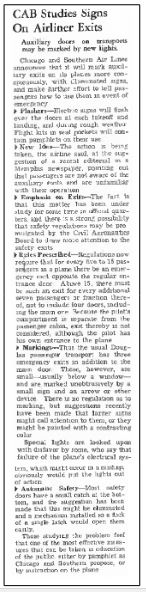

Here is an example of what a VOR/DME looks like on the St. Louis Aeronautical Sectional Aeronautical Chart showing the Samsville VOR:

Image Courtesy: Phil Brooks via Public Domain.

Some are hard to find from the ground, because they are located on ridges or mountaintops, to provide an unobstructed signal. Others are easy, located right on airports. Their locations can be viewed on charts accessible via www.skyvector.com. In the “old days” before smartphones, I went on a few “wild goose chases” where I was unable to locate a VOR from ground level, much to the frustration of my wife! The Google Maps website (maps.google.com) has made it a lot easier to find them in advance of a search. Some come up in a location search, but for others you must enter the latitude and longitude (available from www.airnav.com).

When taking pictures of VORs, it’s important to stay on public property or get permission from the landowner. I’ve met some nice people this way, but it sometimes takes a bit of explanation as to why I am interested! I like that some people, even landowners, who receive payment for the use of their land, don’t know what those “bowling pins” are for.

I am a member of the Airline Dispatchers Federation (www.Dispatcher.org) and post a photo every month of a VOR, with clues as to its identity, for people to guess. Check it out, you don’t need to be a Dispatcher to play! The website can also be used to learn about the Dispatch profession, which I love.

Pictures of VORs from Captain’s Log readers around the world would be appreciated!

This article is dedicated to my wife, Pam, for putting up with many “VOR hunts,” and also to retired FAA technician Bill “Guido” Hyler, who has answered many of my VOR questions over the years.