Airline Schedules,OAG,Official Airline Guide,timetables

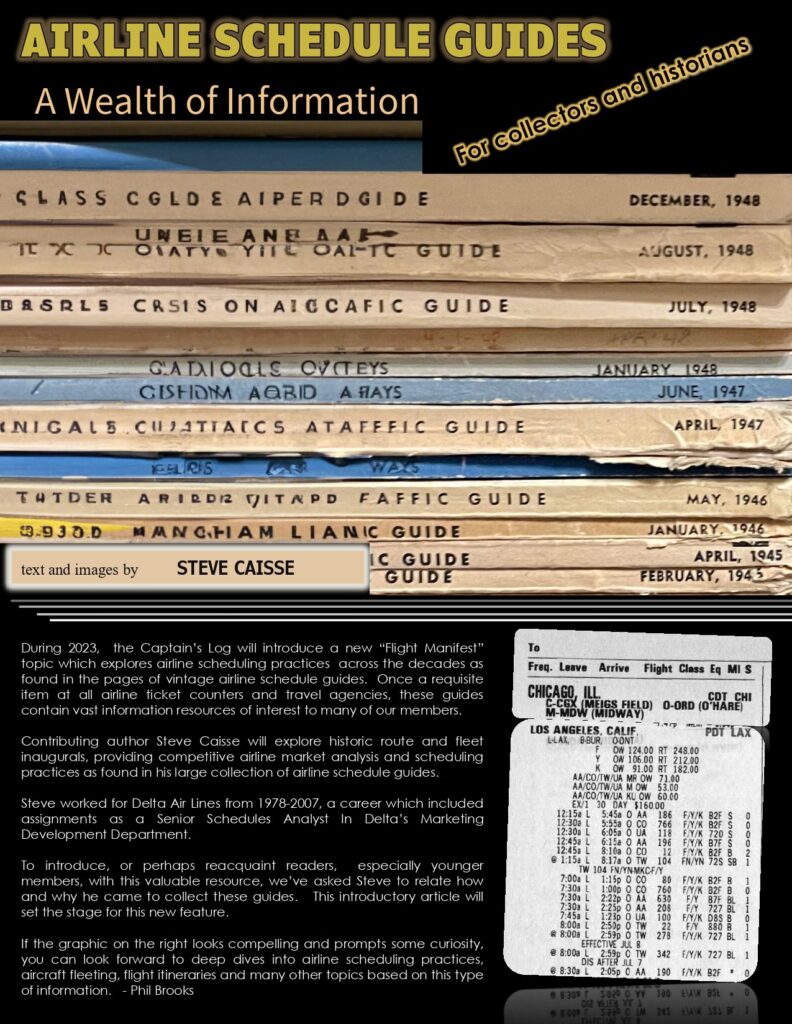

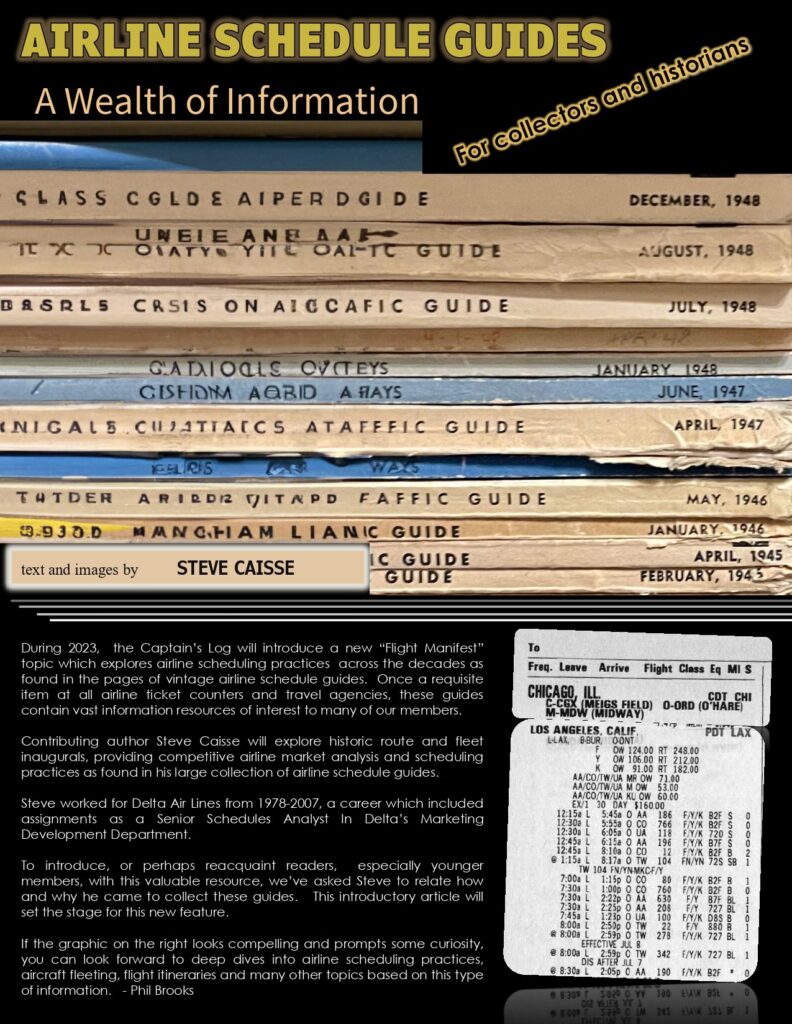

Airline Schedules: A Wealth of Information

By Steve Caisse

Follow this link to view this article as a pdf.

Follow this link if you’d prefer to download this article as a .pdf.

Airline Schedules,OAG,Official Airline Guide,timetables

By Steve Caisse

Follow this link to view this article as a pdf.

Follow this link if you’d prefer to download this article as a .pdf.

Inaugural,Jon Proctor,L-1011,TWA

By Dennis Danesi

Way back in July 1972, I was heading with my parents to Los Angeles to visit Disneyland. This was going to be my very first time flying on an airplane and I was thrilled to learn that we were flying aboard a TWA 747. I was already in love with aviation as my Dad would take me to Chicago O’Hare Airport all the time to see the planes and walk around the terminals (back when you could do that) and he would even ask a Pilot or Flight Attendant to take me onboard an airplane for a few minutes just to see the passenger cabin and cockpit.

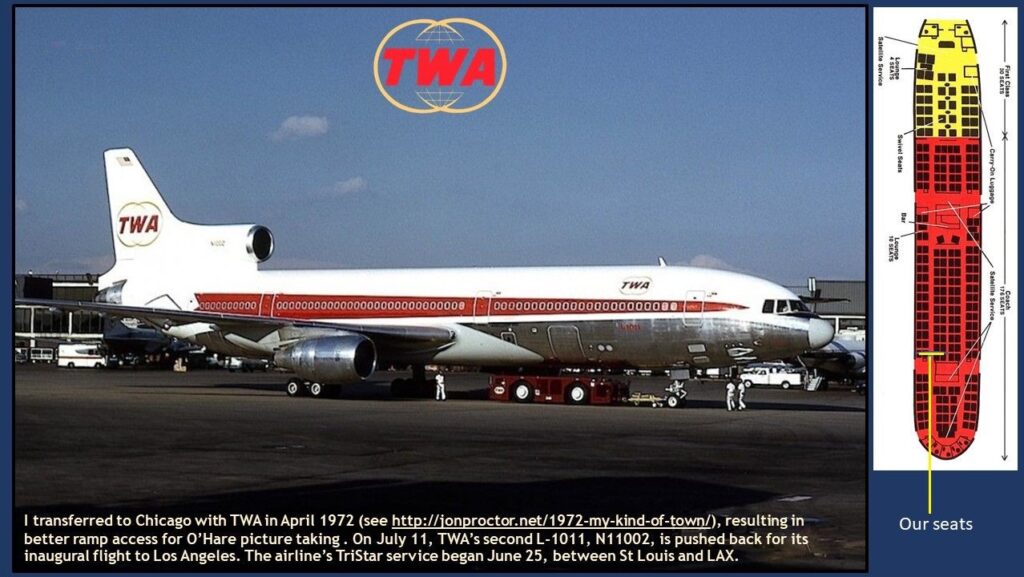

However, as things usually go, we received a call from our Travel Agent telling us that we were no longer going to be flying on a 747. TWA put this new aircraft on the route and we were going to be on their inaugural L-1011 flight. I was NOT happy at all, what was this L-1011 thing and why can’t we fly a 747?!?!

When we arrived at the airport that day, I remember the news media being there. On board, they gave us beach towels as a remembrance of this inaugural flight.

I remember the Captain visiting the cabin and greeting passengers, including myself!!

Here is the crazy part, I have always wondered which TWA aircraft I was on for my first flight as a kid.

Fast forward to a couple of years ago. I was starting a page on Facebook for Past US Aircraft and Liveries (US Airlines Past Liveries and Aircraft | Facebook) and was searching for photos. I came across the photo below and the caption Mr. Jon Proctor wrote. Needless to say, I was blown away. My family and I were on that exact aircraft when Mr. Proctor took the photo so many years ago. I only wish I had known sooner to share this with him. His photos are amazing and I am glad that I found his site.

Editor’s Note: This is why we at the World Airline Historical Society keep the late Jon Proctor’s website alive, for great stories such as this. Do you have a story to share about a memorable flight or an aviation collectible? We want to hear from you! Leave your comments/contact information below or send us an email. We regret we are unable to publish all submissions.

History,Safety cards

By Fons Schaefers

Introduction

In the previous issue, we saw that in the mid-1960s safety cards became mandatory. This caused a proliferation of safety cards and parties being involved in their design and production. It set in motion some trends and developments that shaped the appearance of safety cards until this day. Let’s review them.

Expansion

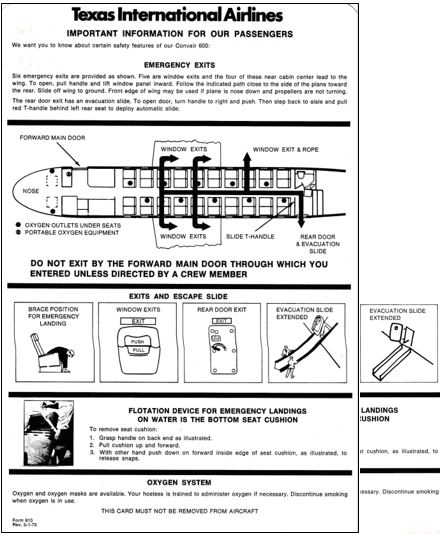

The first trend was that, now that safety cards were mandatory, all airlines applied them. This included smaller airlines such as regional and air taxi operators which before did not have them. The USA led, but many other countries followed suit. A US example is Texas International Airlines, a local airline operating Convair 600s and DC-9s. It earned its “international” nomer because it flew across the border to Mexico. Its 1970 Convair 600 card has a mix of drawings and text, in English on one side and Spanish on the other. A revision of the card 2.5 years later is identical except for the evacuation slide. This is now of the inflatable kind, but who noticed?

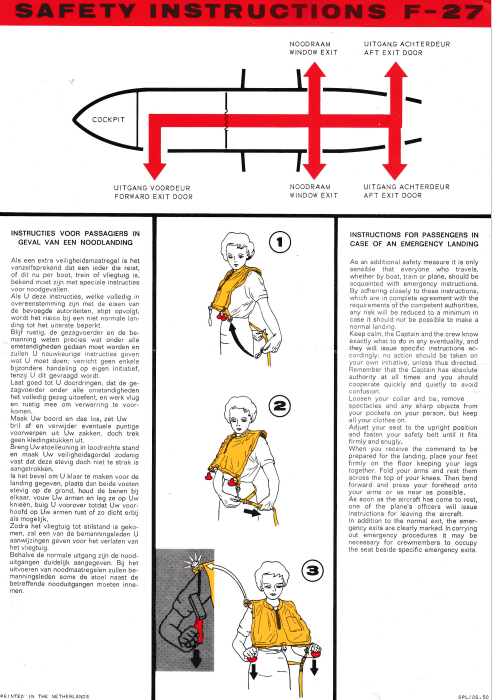

An early example from Europe is a card for the Fokker F.27. Although it does not say so, this card was in use with NLM. That stands for Nederlandse Luchtvaartmaatschappij – Netherlands Airlines, which started in 1966 and was affiliated to KLM. Initially, it flew domestic routes only with two F.27s leased from the Royal Netherlands Air Force, but gradually expanded into a regional carrier. It exists today as KLM Cityhopper. The card reproduced was its first card and dates back to about 1970. Its design did not follow the style in use by KLM at the day. Rather, it was copied from a sample made by Fokker, the aircraft manufacturer. Text prevailed, in Dutch and English on the front side, German and French on the back. The title however was only in English – on both sides.

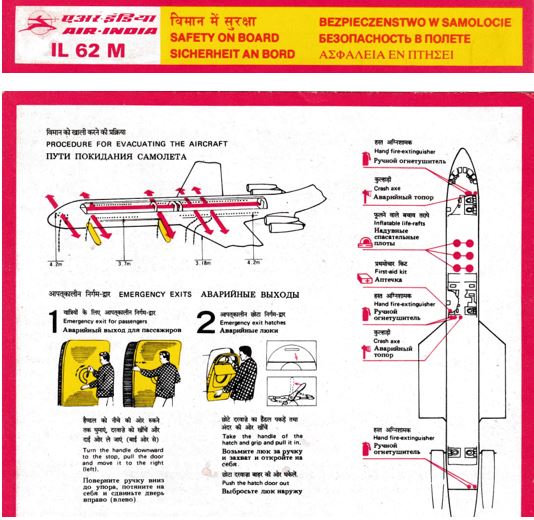

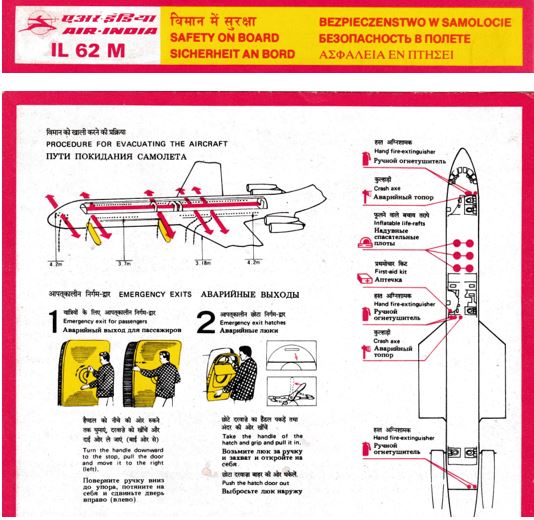

A trend that emerged in the 1970s and 1980s was leasing of aircraft between airlines. There are many varieties of leasing. For the safety card collector, the most interesting one is where there is a mix of features on it from both the lessee (the airline that leases in) and the lessor (the airline that leases out). An example is the Aeroflot Ilyushin 62 that was leased out to Air India in the late 1980s. For the passengers, it should have the look of Air India, hence the Air India logo. All text is in three languages: Hindi, English and Russian, except that the header has three more languages: German, Polish and Greek, probably a remnant from the Aeroflot example. Note the distances to the ground from exit sills. Only Russian cards have this useful information.

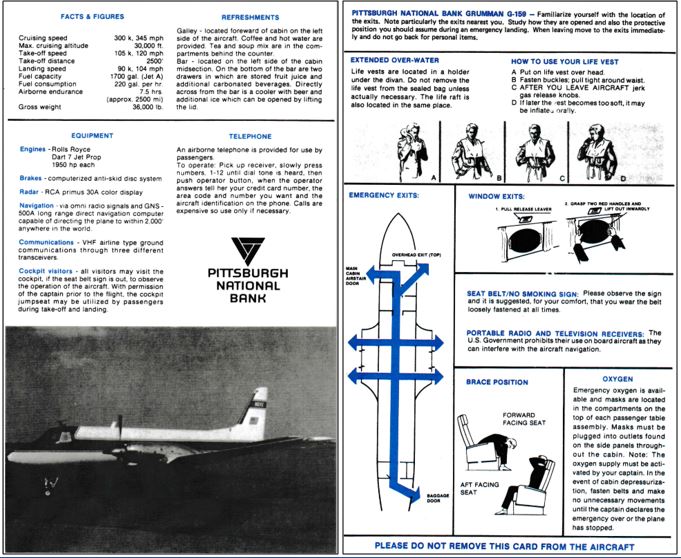

Safety cards also found their way on non-commercial transport aircraft. An example is the Gulfstream 1 operated by Pittsburgh National Bank from 1983 to 1985. This aircraft sat less than 20 passengers so there was no cabin staff on board. The card explains where passengers can find the refreshments and that cockpit jump-seat rides are allowed!

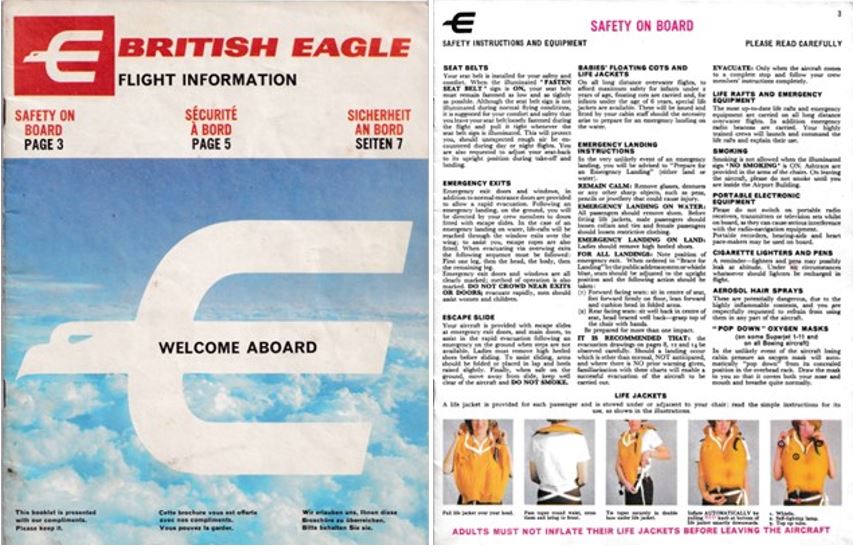

In some countries the introduction of safety cards was delayed. In the UK it remained common well into the 1970s to have safety information included in the company’s in-flight magazine instead of having a separate safety briefing card. See the British Eagle sample in the previous part, and the exit diagrams for the Britannia and the ample-exited Viscount below.

But when indeed a separate safety card was used in Britain, the American rule prohibiting mixing aircraft types with different exit layouts was not always followed. This mid-1970s Dan-Air card showed both the 727-100 and the 727-200. Although seemingly of the same length, the -100 was actually significantly shorter and had a different exit layout. Some of you probably spotted the error for the 727-100: side exits aft of the wing! These were only on the -200, weren’t they? Actually, this was not an error. In the early 1970s Dan-Air obtained short body 727s from Japan Airlines and converted them into a high-density seating layout. For that, two extra, opposite exits were required by the British Civil Aviation Authority (CAA).Below photo, courtesy of I Spashett, shows G-BAEF’sleft side with the new exit just added, awaiting painting in Dan-Air colours. Reportedly, they could sit 153 passengers, but I doubt whether that figure is correct. An already very cramped layout on Seating Plans – DAN AIR REMEMBERED shows 144 seats. Perhaps the 153 figure included the crew?

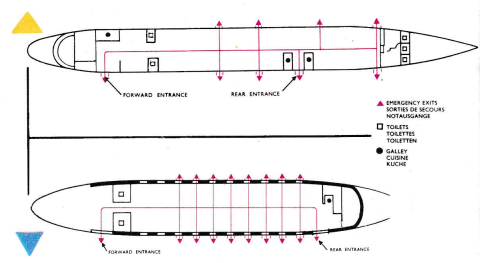

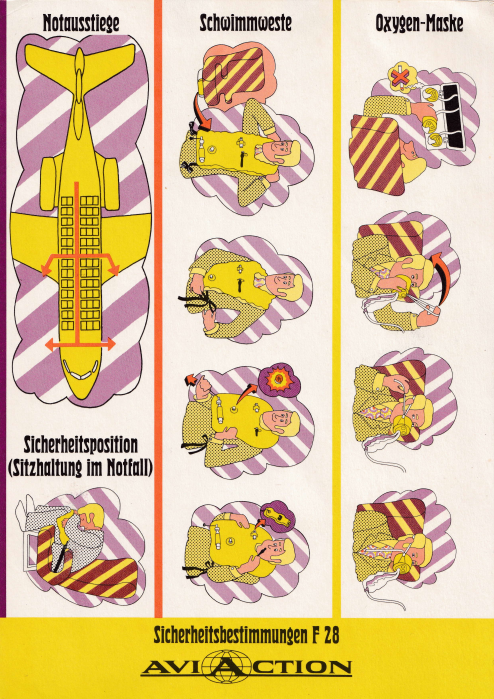

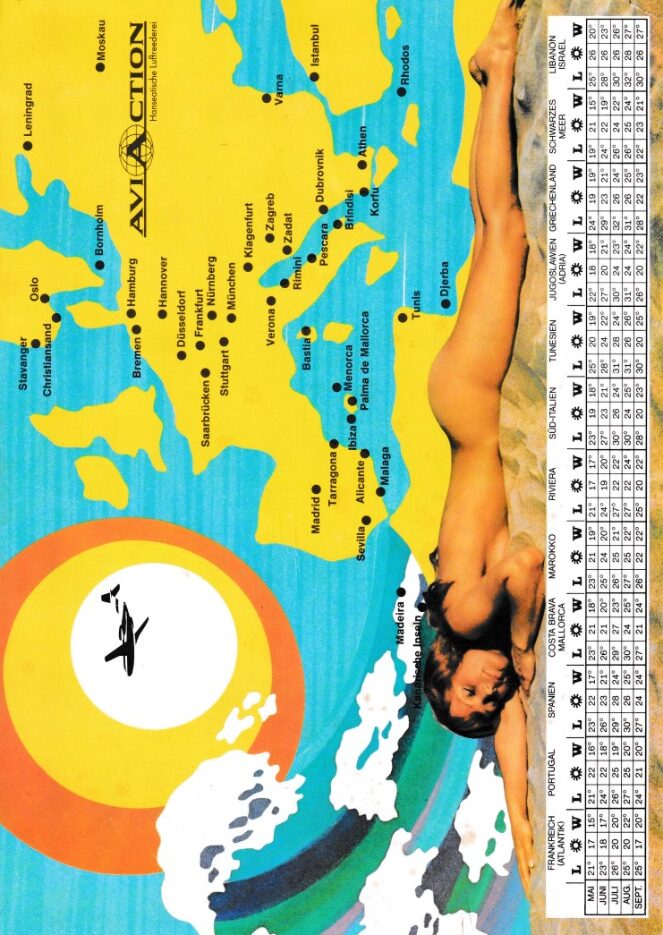

In China, aviation safety was not a priority until well into the 1990s. It was common for airliners not to have any safety card on board, or the wrong one, stowed away in a hat rack, as the author experienced in 1989 when flying on a CAAC Hawker Siddeley Trident but finding a CAAC BAe 146 card. Another airline that did not take safety cards too serious was Aviaction from Germany. One side of its card shows the bare minimum of safety features, the other side presents the destinations of this holiday charter airline and a beach lady in bare minimums as well, clad only in sunscreen. Aviaction flew three Fokker F.28s between February 1971 and October 1973.

Pictorials and Pictograms

Another trend, developing slowly, was that of pictures replacing text. Already in the 1950s, airlines started to add illustrations to their text-based safety leaflets. Still, even two decades later, there were many safety cards where text prevailed with illustrations in a supportive role only. Gradually, this reversed into the opposite. Pictures became primary and text became supporting. There were several reasons for that. One is the adage of “a picture is worth a thousand words.” Another is the multitude of languages. Whilst for domestic US airlines, English was the dominant language. Airlines that flew internationally used many more languages. This took up much space. As we saw in the previous part, Pan Am in 1969 translated all text in eight languages and needed a booklet for this. It bundled all the illustrations on one fold-out sheet so that passengers could consult it alongside the text. A third reason is that the power of illustrations was recognized by the authorities and became formally recommended, as we will see below.

An early reverser was Lufthansa. Its 1973 Boeing 737 card combines texts in six languages with photos.

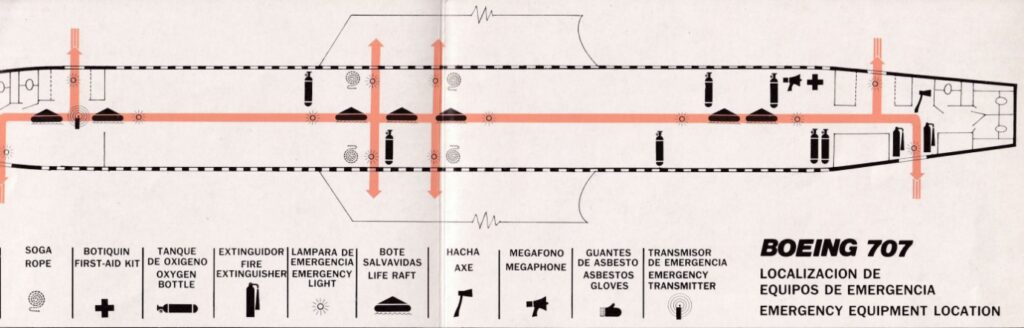

The next year they introduced an illustrations-only format. At the top of the card they added an index using pictograms. These pictograms were explained by text appearing in no fewer than 13 languages. See the Boeing 707 example, dated June 1974. Lufthansa thus became a trend-setter.

Not only was the concept of pictograms copied by many others, but often also Lufthansa’s unique drawing style itself was copied. See for instance Hungarian’s airline Malev with its 1988 card for their new 737. Until then their fleet was dominated by Soviet types.

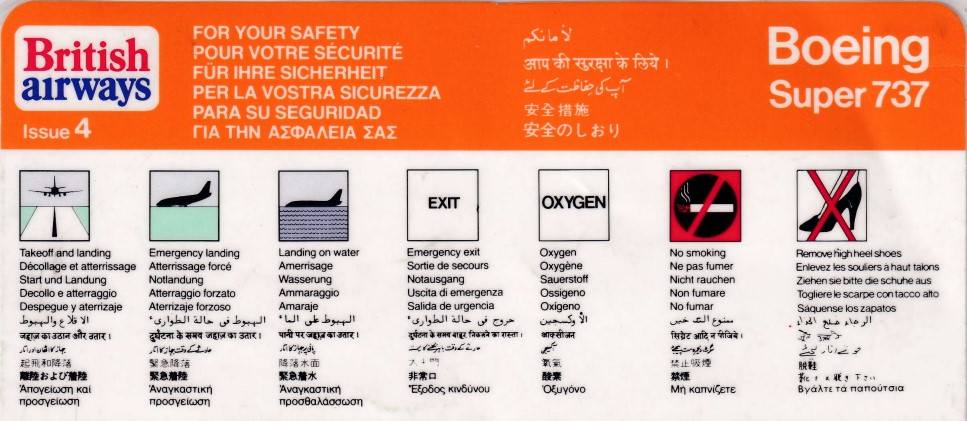

Other airlines used the pictograms concept but developed their own presentation style, such as British Airways, formed in 1974 out of a merger between BOAC and BEA. See their card for the “Super 737” which was just a first generation 737-200. These pictograms were widely copied by other airlines.

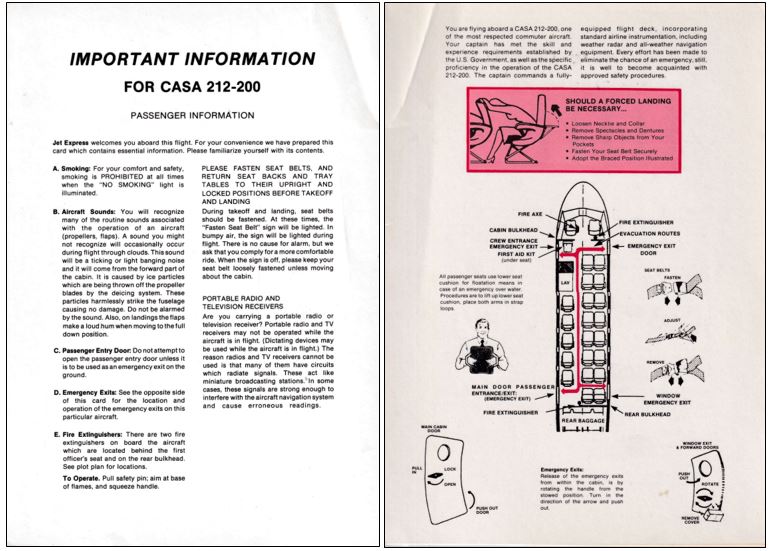

Some small airlines continued to use text based cards. In July 1989 I flew on a TWA affiliate CASA 212 from New York JFK to Atlantic City to visit the FAA Technical Centre. It was a hot day and take-off queues were long. As an alternative to air conditioning, the captain lowered the aft ramp to make us more comfortable. Its safety card, which does not show the ramp as it is not an emergency exit, is reproduced. It lists Jet Express as the operator, even though this small TWA Express carrier never operated jets, only the CASA 212.

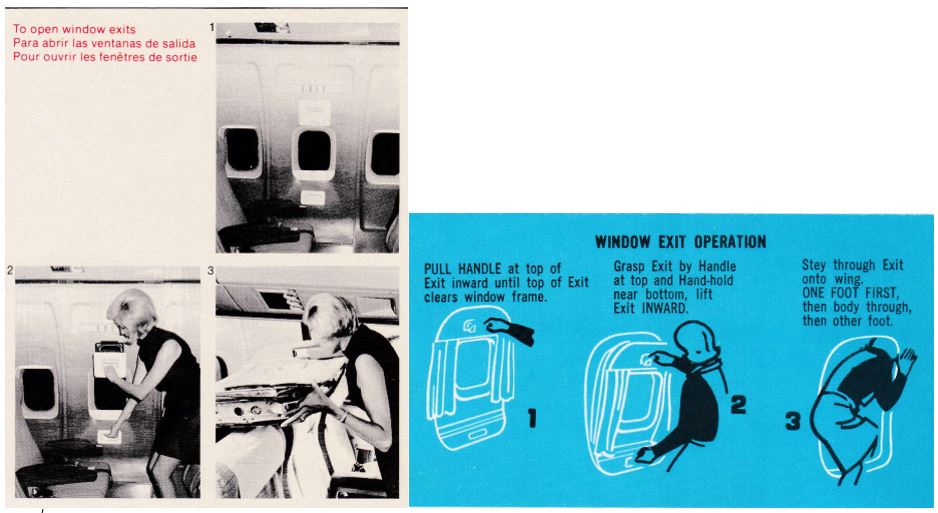

Some airlines, like American, Northwest and United preferred photographs over drawings. In the majority of cases however drawings prevailed. They have the advantage that essential actions and features can be emphasized, and backgrounds can be omitted. Compare the window exit opening presentation on an American Airlines 727 card with that of National Airlines. Which one is clearer?

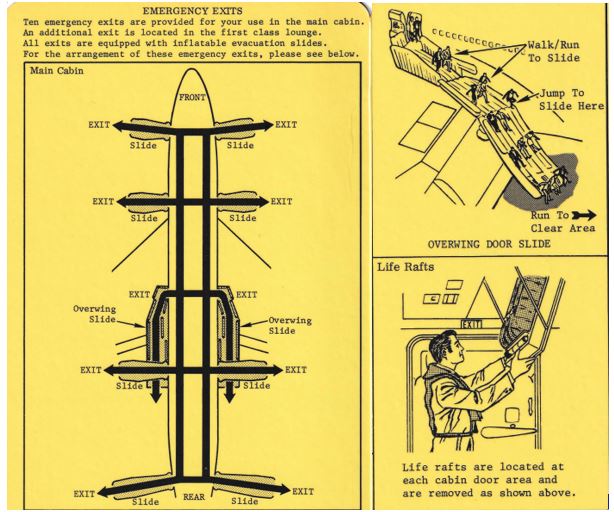

Inflatables Innovation

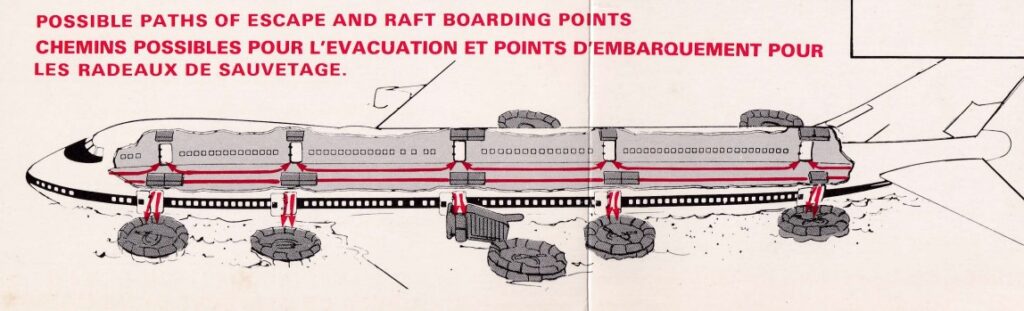

Aircraft escape chutes were invented in 1947. Ten year later, the first inflatable slides appeared. Another ten years later, the first wide-bodies were being developed. These were, initially, the Boeing 747 (four engines), the Douglas DC-10 and Lockheed Tristar (both with three engines) and, from Europe, the twin-engined Airbus A300. These aircraft sat higher off the ground so their slides had to be taller. Exits over the wing led to escape routes down the wings, with heights too high for jumping. So, special off-wing slides were made. On the first 747 cards, these were all nicely and clearly explained. Many initial operators used the same drawings, supplied by Boeing. I show panels from the Continental May 1970 card, which were identical to those of American, United or Wardair. Early 747s had separate life rafts, typically stowed in ceiling lofts, as shown by Continental. Wardair even showed a raft launching scheme. Later, the explanations got more terse, or disappeared completely, leaving only graphics, with passengers possibly puzzled as to their meaning.

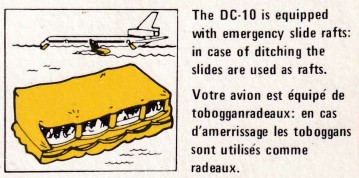

Late in the 1960s, the combined slide/life raft was invented, called slide/raft. It just missed the first 747s, but all overseas DC-10 and Tristar cards show slide rafts. Nigeria Airways’ DC-10 card had the best explanation: “in case of ditching the slides are used as rafts.”

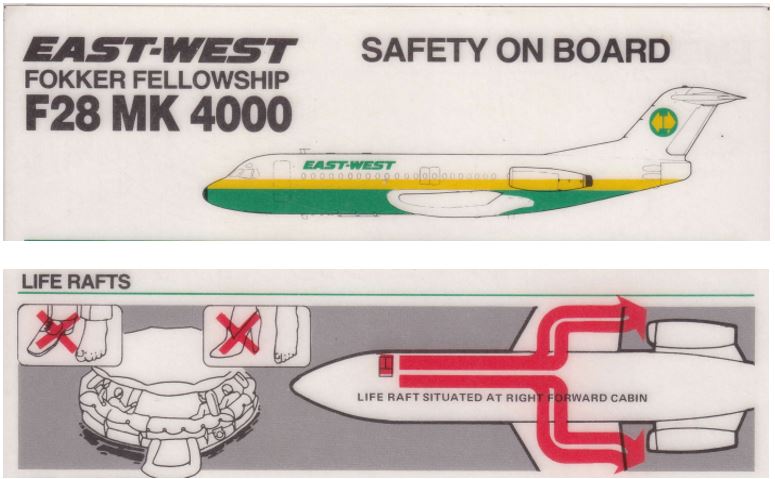

Gradually, also 747s were so equipped and separate life rafts became rare on long haul aircraft. Short haul aircraft did not need them, but there were exceptions. In the mid-1980s, East West was an Australian Fokker F.28 operator that served Norfolk Island, which is in the Pacific about 1,400 km (870 miles) from Australia. For that route, it carried life rafts near the front doors, but the safety card explains that for launching they should be carried to the overwing exits. They never had to put this to practice.

Effectiveness and Dedicated Companies

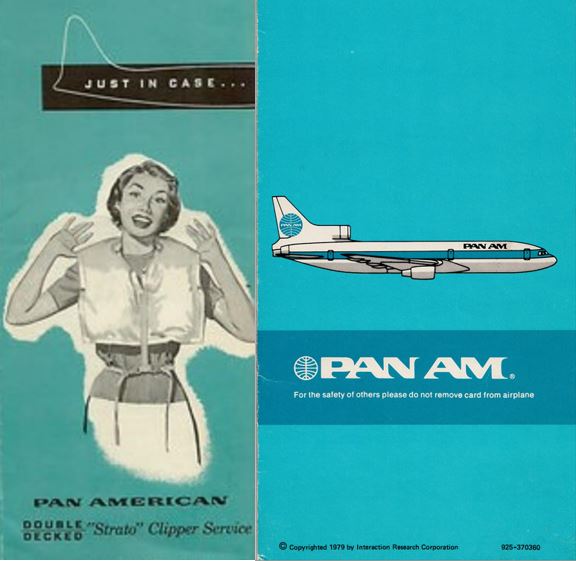

Few, if any airlines, tested the effectiveness of their cards, be it text-based or illustrations-based. The same applied to the manufacturers of aircraft, with one exception. Douglas Aircraft Company, a leading manufacturer of airliners since the 1930s, in 1967 hired two psychologists to do research in passenger safety systems and the effects of panic in crashes. They studied passenger behavior and experimented with passenger education methods. The safety systems that they studied were those typically appearing on safety cards such as exits and their operation, seat belt use and oxygen systems. But they also improved exit signs and lighting in the cabin and placards. After six years, they left Douglas (which now was McDonnell Douglas) and started a company making safety cards. They named it Interaction Research Corporation (IRC). This name reflected their modus operandi, which was to develop safety cards by means of research. They had their cards reviewed by members of the public (‘naïve subjects’) for comprehensibility of its contents. Poor scores needed improving the contents until a satisfactory score was reached. The two psychologists were Beau Altman and Daniel Johnson. Daniel also sat in the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) panel for cabin safety and was instrumental in developing the first set of guidelines for cabin safety cards, published by the SAE in August 1976 as Aerospace Recommended Practice (ARP) 1384.

IRC started in a garage in the Long Beach, California area, where Douglas was based, but later moved to the state of Washington – Boeing territory. Their registered trade mark (™) was Just in case. The same tagline had been used by Pan Am on their 1950 safety leaflets, then not trademarked. Incidentally, Pan Am was one of the users of IRC material so their safety cards carried the Just in case line again.

Neither Beau nor Daniel were artists, so they hired illustrators for drawing the pictorials. Unintentionally, they thus created a pool of professionals who later started on their own. This explains why today there are quite a few safety card making companies in the state of Washington. At one stage, Beau Altman had its own company. I reproduce the 1988 Air Ontario Convair 580 card. Note the tagline: For Your Safety, not trade marked.

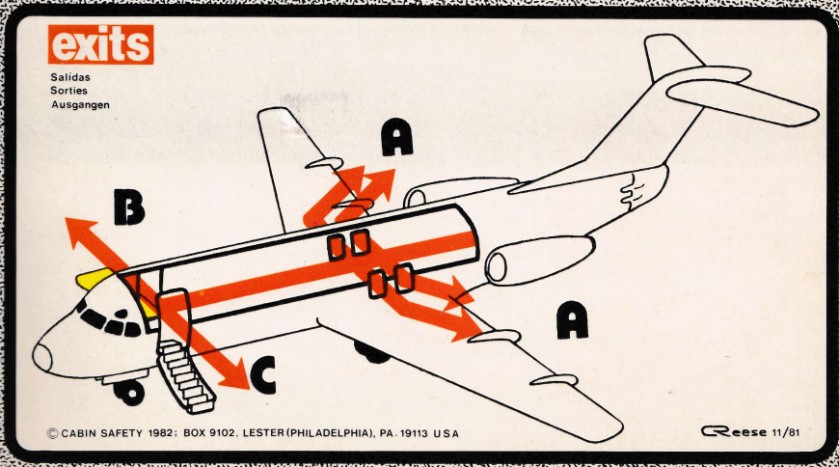

On the East Coast, male flight attendant and vivid collector of safety cards – probably holding the world record in number of unique samples – Carl Reese, was an artist himself and started in 1981 a one-man safety card producing company. He named it Cabin Safety Inc., trademark Cabin Safety. His garage was his own home in Lester, PA, near Philadelphia. After having lived for a while in nearby, quiet Cecilton, MD and renaming his company as Cabin Safety International, he emigrated to Calgary, Canada. Readers of the Captain’s Log will recognize his name, or may even have met and traded with him. He ran the Log’s safety card section in the 1980s and often visits Airliners InternationalTM conventions. An early safety card of his hand is for Altair’s Fokker F-28, drawn November 1981. Carl also tested his drawings on naïve subjects, but not at the same scale as IRC.

Whereas IRC mainly served large airlines and heavier equipment, Carl’s clientele primarily consisted of smaller airlines and private operators, with associated lighter aircraft. Where Pan Am used IRC, Pan Am Express (formerly Ransome Airlines) used Cabin Safety. Its ATR42 flew routes both in the USA and, before the wall fell, between West Germany and Berlin. For the latter, Carl made a version with German as primary language.

Regulatory Actions

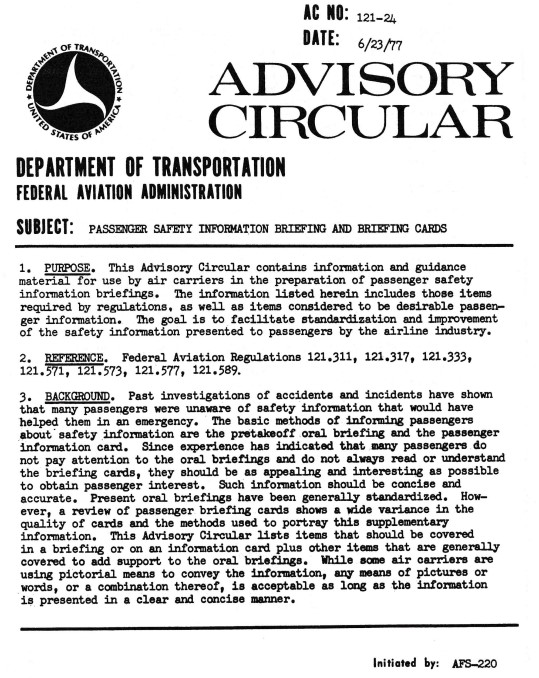

The 1970s’ spike in survivable, yet fatal accidents caused concern with the US congress. Its members, coming from all of the US states for meetings in Washington, D.C., were frequent flyers and could well relate to it. The House of Representatives organized a series of hearings aimed at improving cabin safety, occurring almost annually between 1976 and 1990. In July 1977, the focus was on passenger education. Witnesses interviewed included a survivor of the 1974 Pago Pago crash and Beau Altman and Daniel Johnson. For those interested, search for: Aviation Safety: Aircraft Passenger Education, the Missing Link in Air Safety : Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Investigations and Review of the Committee on Public Works and Transportation, U.S. House of Representatives, Ninety-fifth Congress, First Session, July 12, 13, and 14, 1977. Coincidently or not, the FAA had published just a few weeks before its first set of guidelines for briefing cards: FAA Advisory Circular (AC) No. 121-24. These guidelines augmented the requirements in force since the previous decade. The entire AC can be found on page 118 of the NTSB 1985 Special Study on Airlines Passenger Safety Education (https://www.ntsb.gov/safety/safety-studies/pages/ss8504.aspx).

Both the SAE ARP and the FAA AC set standards for what to present in the cards. Both said that ‘the primary method of presentation should be pictorial’. This accelerated the trend of going away from text and use graphs instead. The list of subjects to be explained does not contain any surprises:

Additionally, for extended overwater operations:

Note that both the exit awareness and location and the ELT guidance was limited to the overwater operations section. This is strange as they would equally apply to overland flights. This was corrected in later updates. The AC also addressed the briefings by flight attendants to passengers, including handicapped passengers. Both the ARP and the AC exist today, updated with many subjects added since the original version, as we will see in the next part of this series.

Comparison

Comparing 1970s and 1980s cards to the ARP and AC reveals some interesting facts.

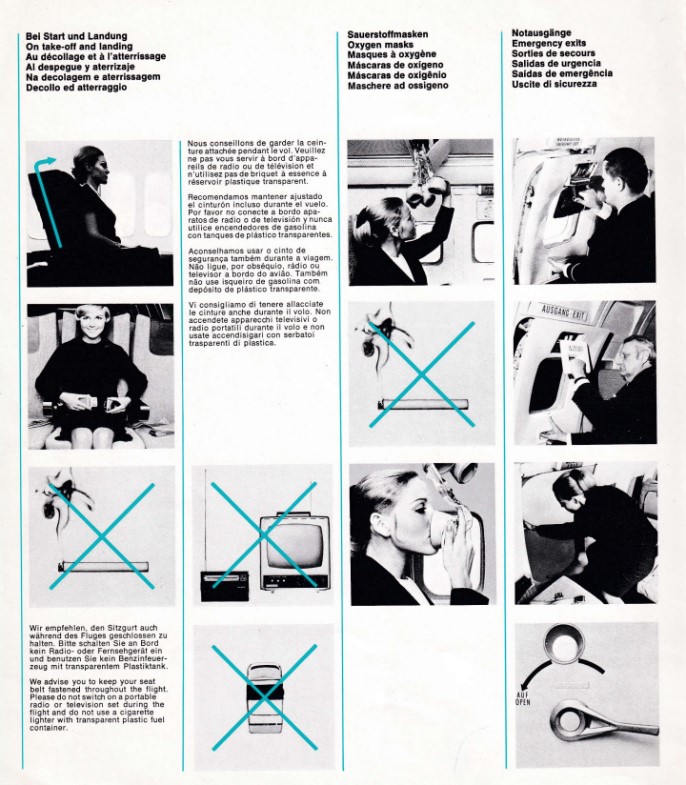

In many cases, airlines covered more subjects than the minimum prescribed. Often, emergency equipment and their locations were displayed even though not prescribed. This also applied to equipment that should not be used on board, such as radios, television sets and cigarette lighters. It was not uncommon to show passengers the crash axe in the rear of the cabin, as Avianca did on their 707. Would they still do that today? Remember, these are the 1970s and 1980s.

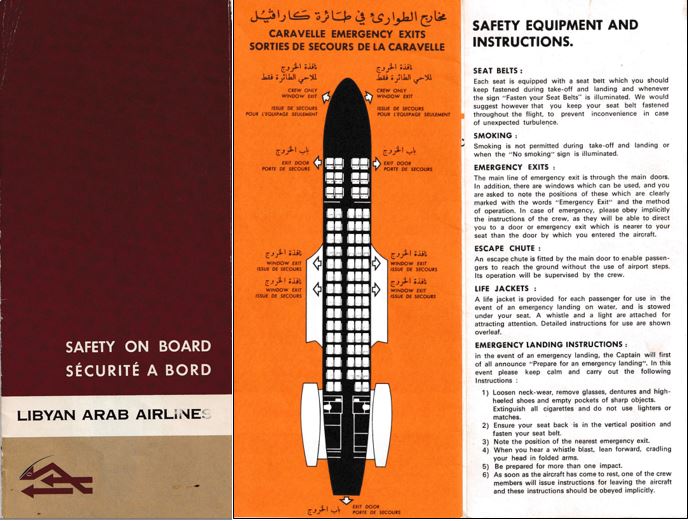

Some 1970s cards still had the emergency landing preparation instructions that were en vogue in the 1950s, instructing passengers to remove glasses, sharp objects and much more. See the sample taken from the Libyan Arab Airlines (LAA) Caravelle leaflet. Libyan Arab Airlines was the new name of Kingdom of Libya Airlines, following the coup in late 1969 by Muammar Gadaffi which ended the monarchy. This leaflet likely dates from 1970 or soon after.

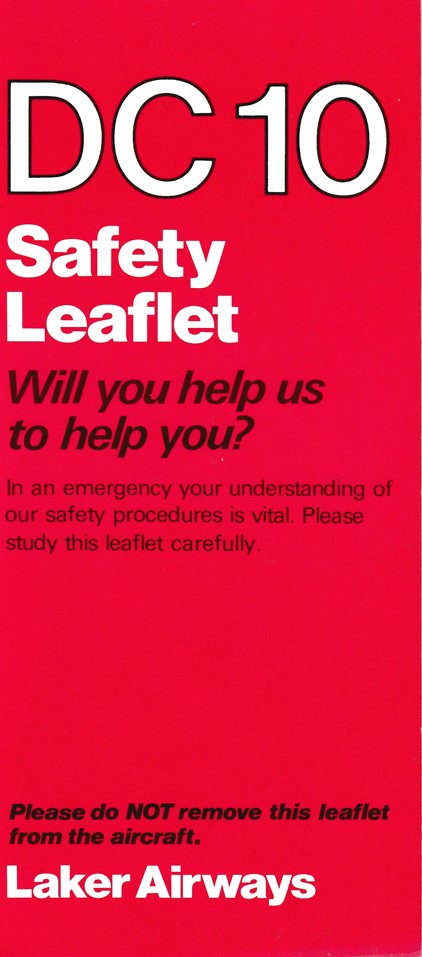

The 1970s saw the phrase “Do not remove from the aircraft,” “Leave on board,” or similar messages gradually appear on more and more safety cards. It is believed that smaller airlines, with lower budgets, started with this, possibly in an attempt to stop having to replenish whole loads of cards after each flight. Larger airlines then took up this practice as well and today it will be hard to find a card without such a text. It is believed that IRC, whose business was to sell cards to airlines, initially only used the phrase when their customers so specified. Cabin Safety had it from their start in 1981.

Both card makers diligently met all the recommendation of the ARP and AC. The only item they typically added that was neither on the ARP nor the AC were instructions for the stowage of hand luggage and the seat back table.

Some airlines that had long stretches over water were late with including instructions for evacuation on water and the use of life rafts. Lufthansa did not have separate water evacuation panels, but showed the use of life rafts or slide rafts where so equipped. The original Laker Airways, which was British and became famous for their no-frills, very cheap “Skytrain” flights between London and New York from 1977 until 1982,only showed life vests and nothing else that would facilitate a ditching evacuation.

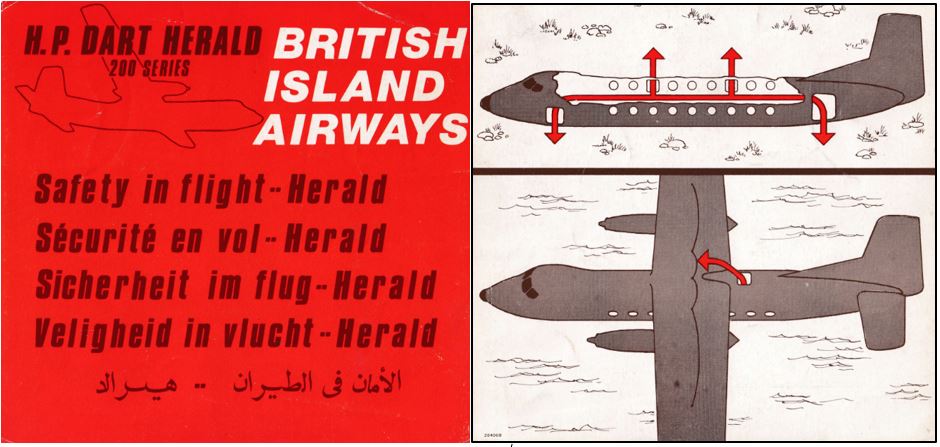

(The later US Laker Airways also used DC-10s and had cards made by IRC, with ditching instructions). Conversely, British Island Airways, which flew the high-winged Dart Herald only a short sector over water between England and the European continent in the 1970s, did show on their cards how to evacuate on water: via the roof of the aircraft and with ropes attached to the wings to hold onto once outside!

In the next part, I will cover the trends in safety cards in the period 1990 to now.

Fons Schaefers / August 2023

Email: f.schaefers@planet.nl

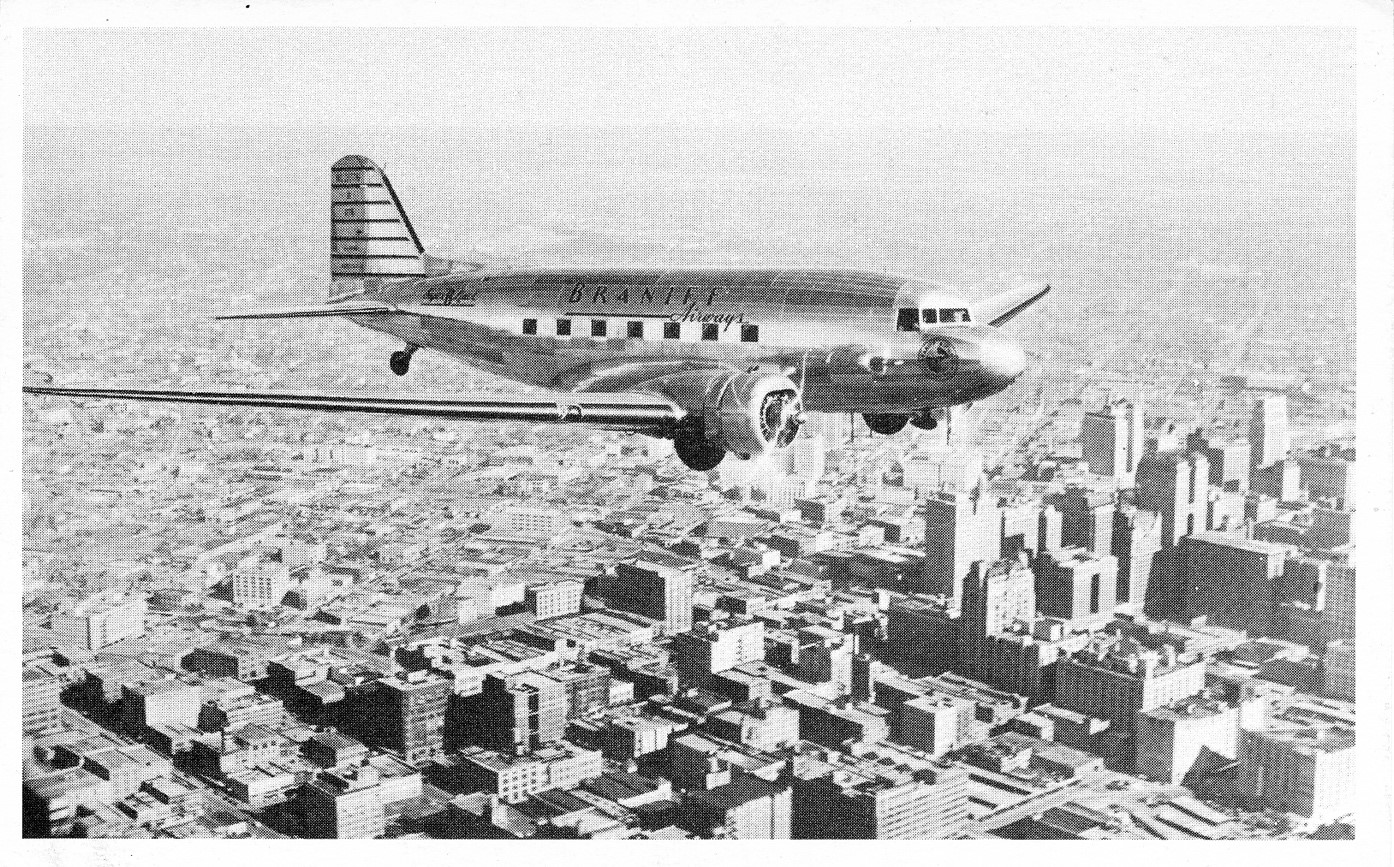

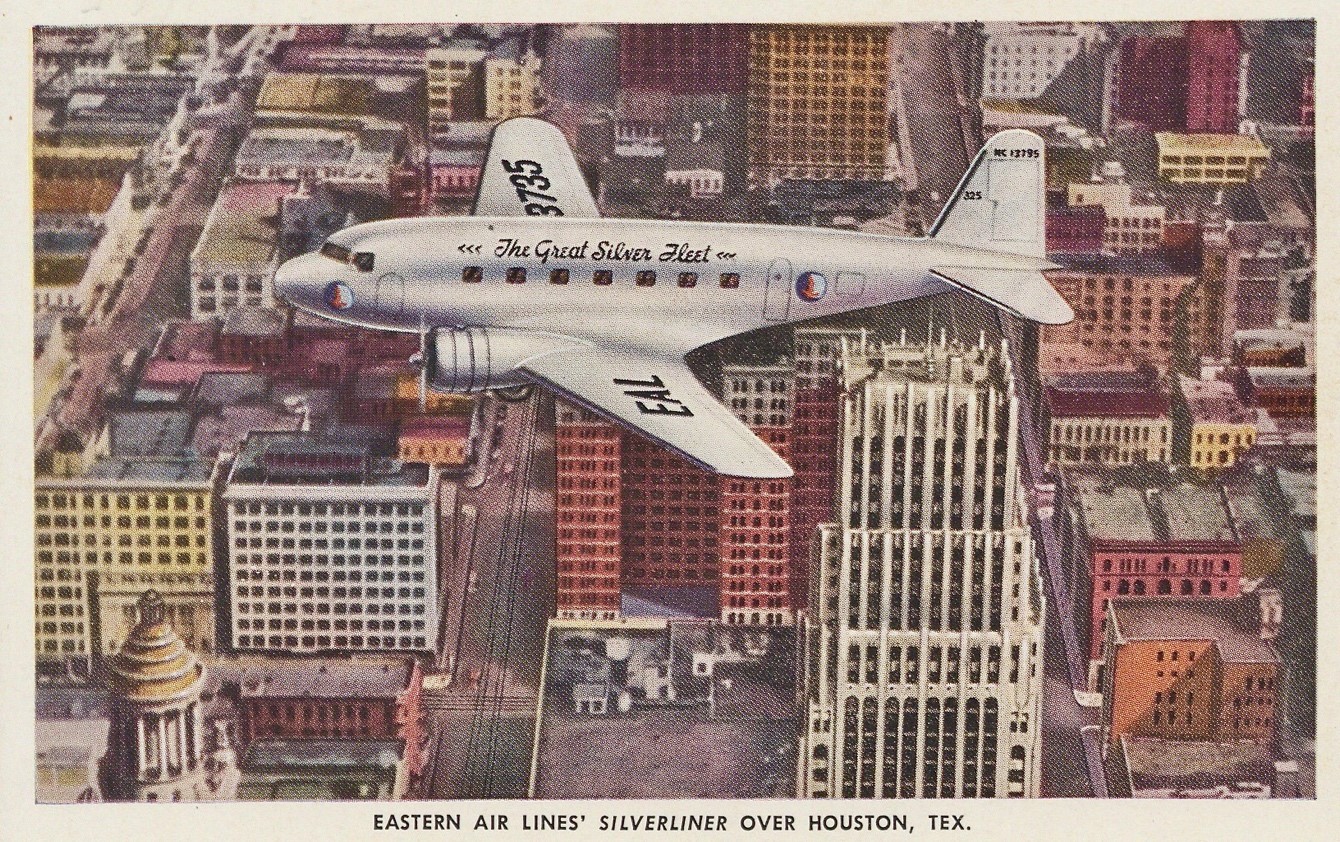

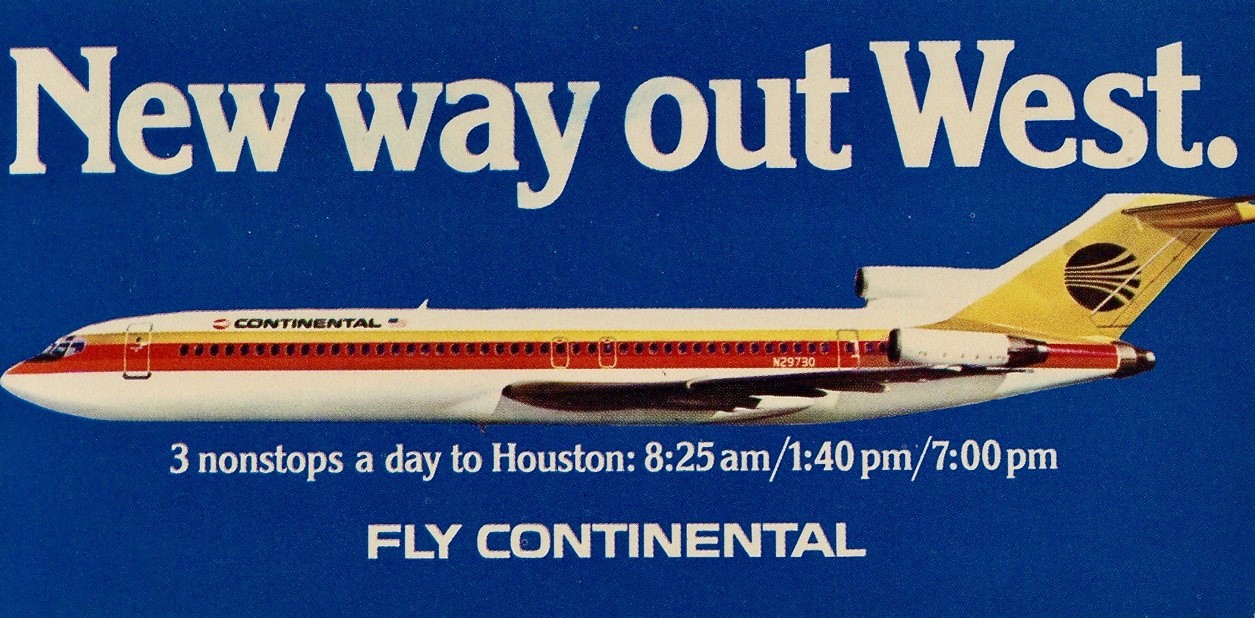

Airliners International,airlines,American Airlines,Central Airlines,Continental,CR Smith Museum,Delta,DFW,Eastern Air Lines,Fort Worth,Frontier,Houston,Houston Hobby,Jefferson County Airlport,Love Field,Meacham Field,postcards,Rio Airways,Southwest,Spirit,Texas,Trans-Texas

By Marvin G. Goldman

A warm welcome to Texas. I hope you enjoy our postcard trip through the skies of the Lone Star State as well as the Airliners International™ 2023 show and convention at Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport.

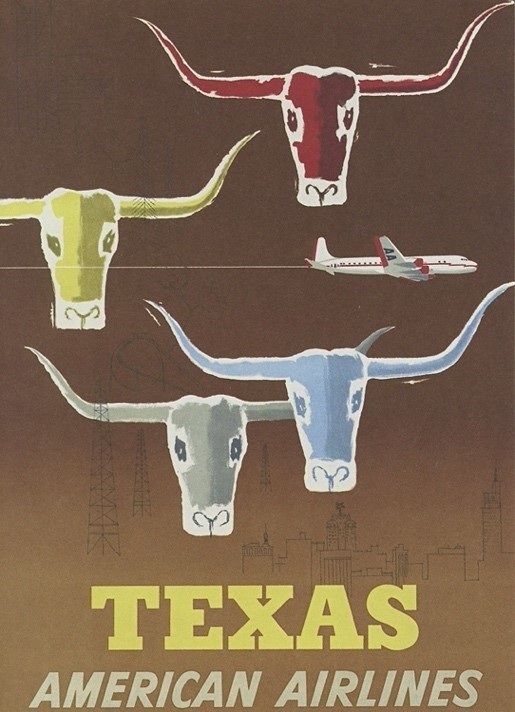

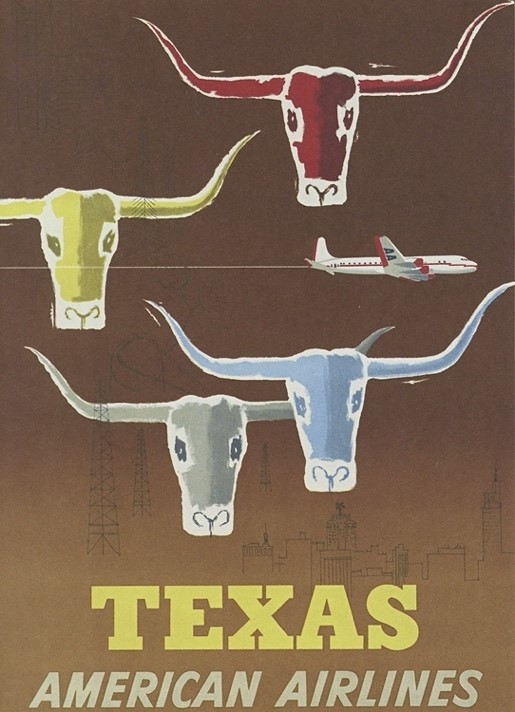

Let’s start with postcards of airlines that served Texas and are now history, followed by leading airlines that continue to operate in Texas skies.

Now let’s turn to some of the leading airlines currently serving Texas. We start with American Airlines which has the longest continuous operating history in Texas and maintains its headquarters in Fort Worth near Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport.

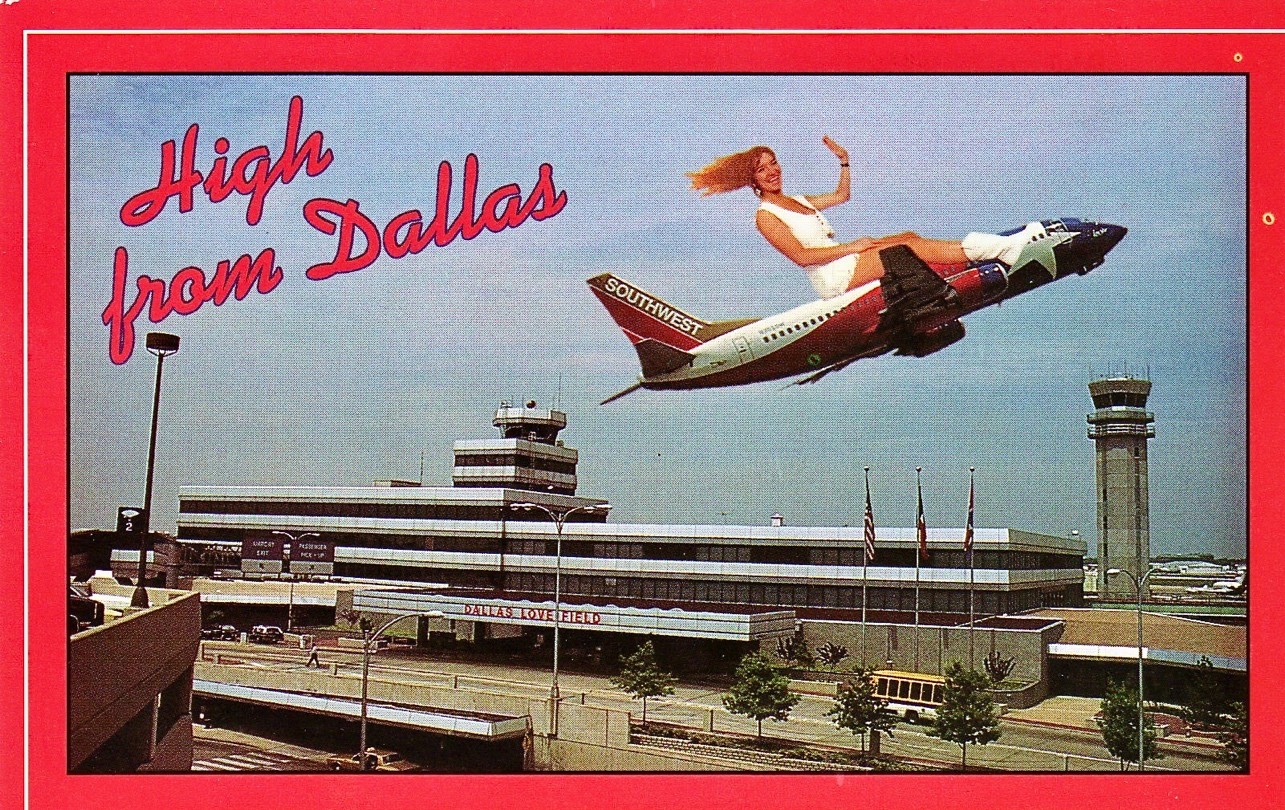

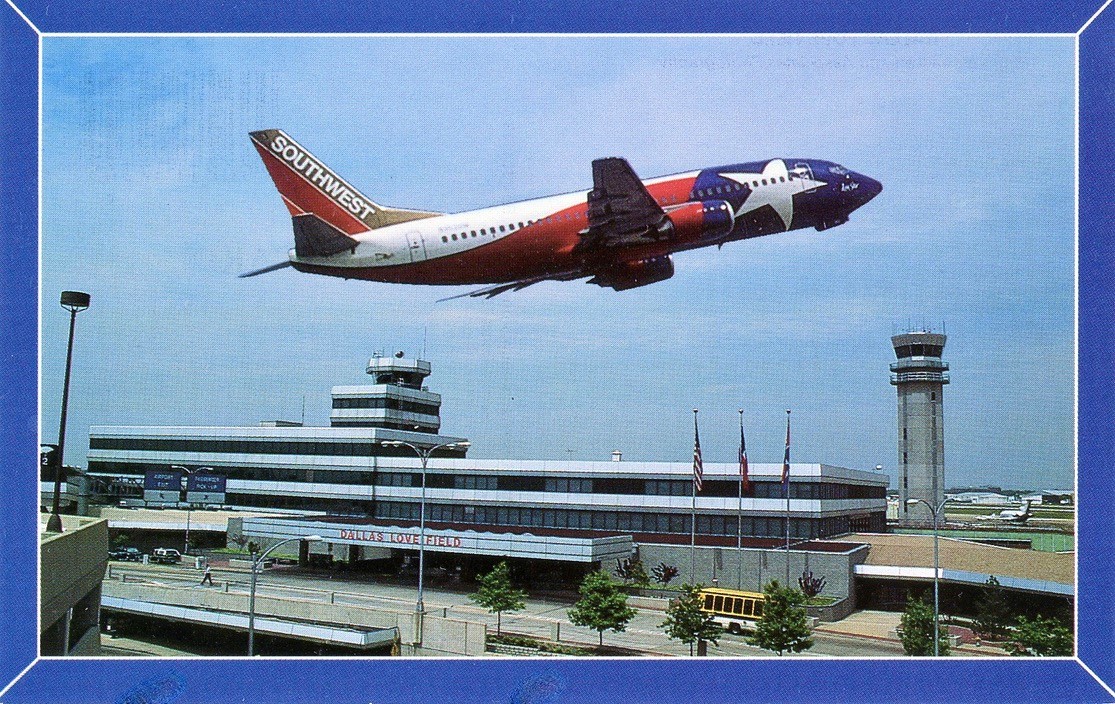

We close with the airline that, along with American, is most associated with Texas skies – Southwest Airlines, also headquartered in Dallas. Southwest commenced operations in 1971 from its base at Love Field, Dallas. At first, it was an intrastate Texas airline, but in 1979 it started expanding to other states and eventually to international destinations as well. Today Southwest is the third largest airline in the U.S. (behind American and Delta) in terms of passengers carried.

NOTES: All postcards in this article are from the author’s collection unless otherwise noted.

Below is my estimate of the rarity of the above postcards:

I hope to see you at Airliners International™ 2023 DFW, June 22-24, 2023, at the Hyatt Regency Hotel, next to Terminal C at Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport. This is the world’s largest airline history and collectibles show and convention, with more than 200 vendor tables for buying, selling, and trading airline memorabilia (including, of course, airline and airport postcards), seminars, the annual meeting of the World Airline Historical Society, annual banquet, tours and more.

Follow this link for more information on entering the postcard, model and photograph/slide contests.

Until then, Happy Collecting, Marvin

airline seat designations

By Fons Schaefers

Anyone who flies regularly as a passenger, even when not necessarily keen on selecting his or her seat of preference, still has an idea of how airliner seats are identified. Seat rows are numbered from front to rear. Across each row, seats are given a letter. Thus, when the boarding pass says seat 21J, the passenger knows not to go and look in the forward section of the airplane but somewhere in the middle. And that it is on the right-hand side. At least, when seen in the direction of flight, because when boarding through a forward door, and walking down the aisle (or one of two aisles, as the case may be), this seat is actually on the left.

This way of identifying airliner seats is universal. But has it always been so? And if not, when was it introduced, and how were seats identified before? Let’s have a look at the history of airliner seat numbering. This article is about the period from the start of air transport to when the current system became common, around 1960. In the next part, I will focus on the years since then.

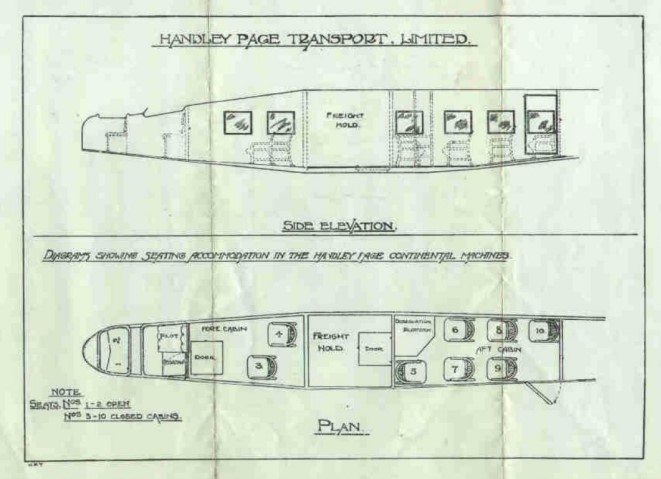

The very first instance of seat numbering likely dates back to the first year of air passenger transport in Europe, or to be more precise: in the United Kingdom in 1919. The Great War was just over and bombers made by the British aircraft manufacturer Handley Page were converted for passenger use. The company started an airline, named it Handley Page Transport Ltd., and offered flights from London Cricklewood across the Channel to Paris Le Bourget and Brussels-Evere, three times each per week. A single-sheet timetable describes the aircraft as “giant,” having the capacity to carry 12 passengers including the pilot and a mechanic. On the reverse side is a seating layout. Of the 10 passenger seats, two were at the front ahead of the cockpit and in the open air, two more were in a closed cabin behind the cockpit, and the remaining six were in an aft cabin, separated from the forward cabin by a freight hold.”The seats were numbered 1 to 10 from front to rear, left to right.

How passengers boarded is not directly clear. As with all period aircraft, it was a tail-dragger. On the ground, the aft cabin was close to the ground but the nose stood up high. The door in the aft cabin required only minor steps. The forward cabin and the open-air seats were inaccessible from the aft cabin and required boarding from outside. Likely, a tall ladder was used and only athletic passengers were allocated to these seats. In the forward closed-cabin, the plan marks a “door,” which I believe was in the fuselage bottom, accessible by the ladder.

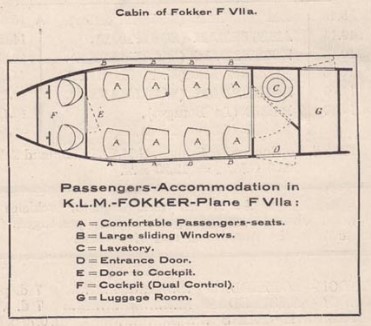

This early way of assigning numbers to seats was exceptional. Other airlines in the pioneering decade did not use seat numbers. I reproduce a cabin chart for the popular Fokker F VIIa as used by KLM in the mid-1920s. All eight passenger seats are identified as “A = Comfortable Passenger-seats.” There is no sign of seat numbering.

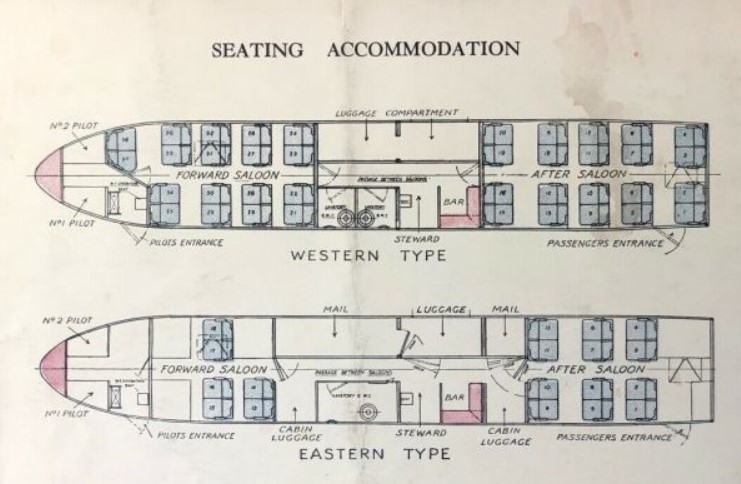

ln Great Britain in 1924, Imperial Airways was formed by a merger of Handley Page Transport and three other airlines. Handley Page continued building airplanes. In 1931, the Handley Page H.P.42 was introduced. Imperial used it in two versions, called the Western type and the Eastern type. The former was operated on the shorter routes in Europe (mostly London Croydon-Paris Le Bourget). The Eastern type was used on longer routes, such as from Cairo, Egypt to Karachi in what was then British India. Their seating capacities differed significantly: 38 on the Western type and only 18 on the Eastern type. In either variant, the passenger entrance door was at the extreme rear, on the left, and the seat numbering started there: left to right, rear to front.

At a later stage, the capacity of the Eastern type was increased with three double seats. These were placed at various locations across the cabin, but the original numbering was not changed. The result was that the additional seats were numbered out of sequence, creating a seemingly haphazard numbering pattern.

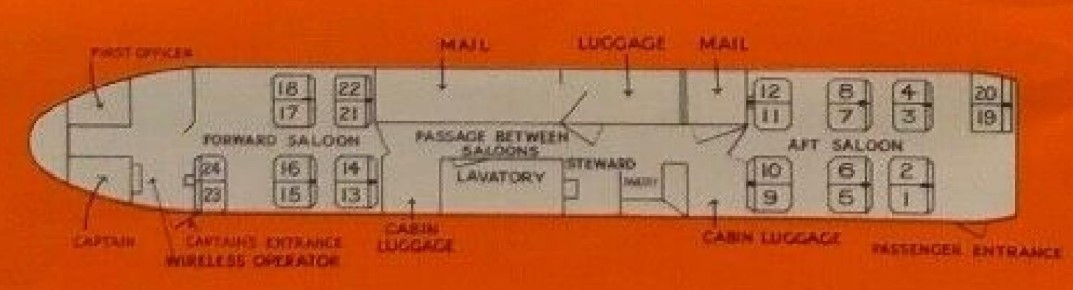

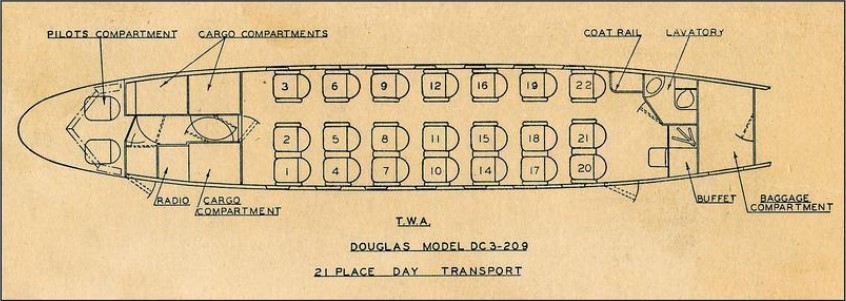

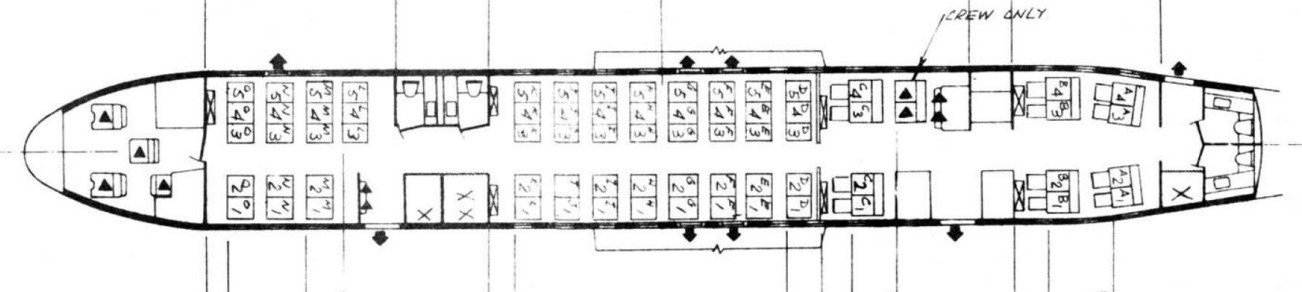

Later in the decade, when air transport in the USA had taken off and surpassed in volume that of Europe, the Douglas DC-3 was the aircraft type in use by the main airlines. Transcontinental & Western Airlines (TWA) was one of them. Their operations at the time were confined to the United States. Only after the war would it become an intercontinental airline and change its name to Trans World Airways). TWA published the seating layout shown below. Seats were sequentially numbered from left to right, front to rear. Number 13 was omitted, as it is regarded in Western culture as the “unlucky” number.

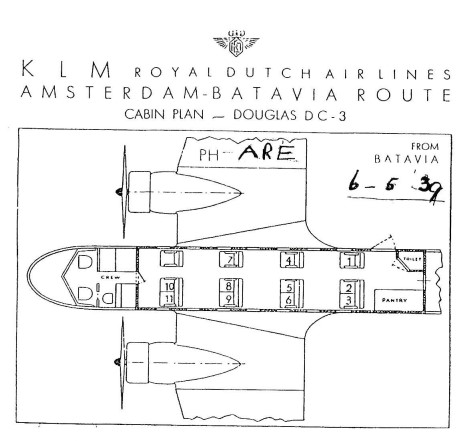

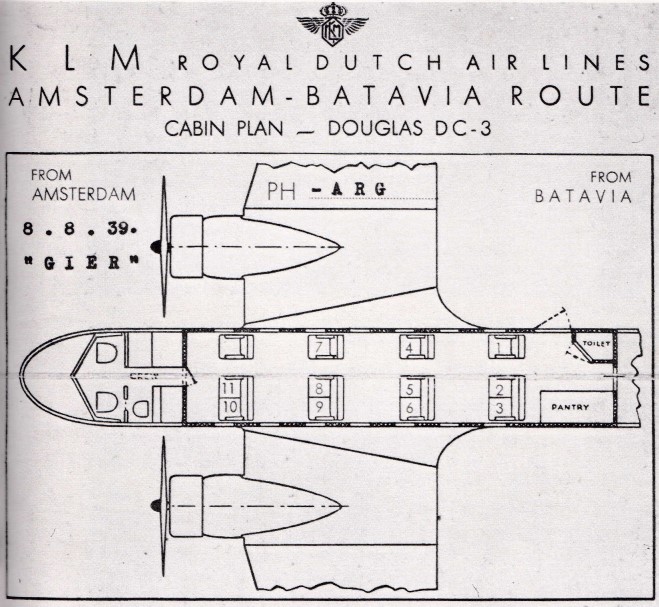

KLM Royal Dutch Airlines operated the DC-3 on what was then the longest air route, between Amsterdam, the Netherlands and Batavia, Netherlands East Indies (now Jakarta, Indonesia), taking five days and making 19 stops. Rather than fitting it with the normal DC-3 seating capacity of 21, only 12 seats were installed as seen in the below seat plans. One of these was non-saleable as it was for the steward. This was always a male, as KLM scheduled its stewardesses on the European routes only. The remaining 11 seats were numbered radiating from the passenger entrance door (located aft on the right side), so from right to left, and rear to front. Seating diagrams together with passenger names and their destination were made up for each flight and distributed to all on board. Current privacy rules and ethics did not exist then. I reproduce two plans, without the list of names. The first is for the flight starting in Batavia on May 6, 1939, and the second is for the flight departing Amsterdam on August 8, 1939. Note that in the latter the numbering sequence was reversed in the front row (seats 10 and 11). This may have been a typo, as the other plan did not have this anomaly.

The flight on August 8 would be one of the last on the route. With the outbreak of war in Europe a few weeks later, the route was initially truncated (starting at Naples instead of Amsterdam) and later terminated entirely.

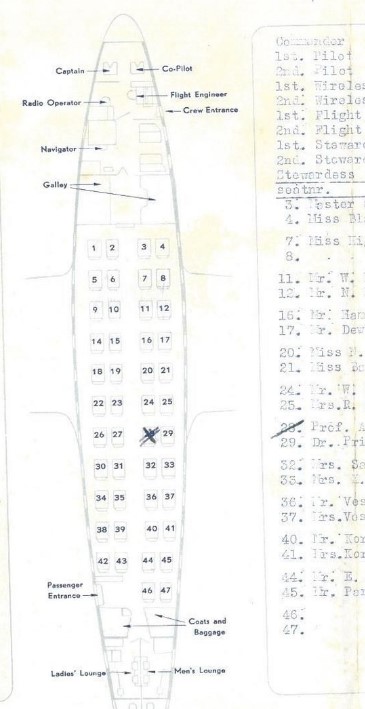

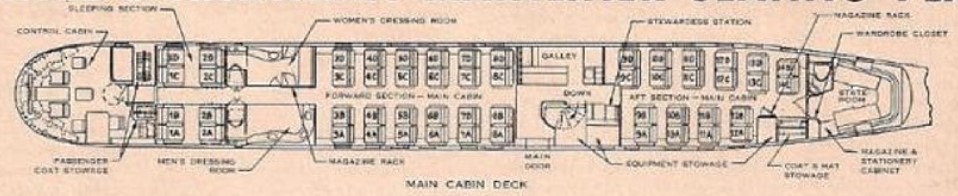

While Douglas was the most successful manufacturer of airliners just before the war, Boeing tried to take its stake in the market with the Model 307, also known as the Stratoliner. It was unique in many respects: it was the first pressurized airliner and its cabin layout was asymmetrical, with four compartments seating six each on the right side, and a single row of nine seats on the left. Such a layout is reminiscent of European long-distance train coaches but has never since been repeated in air transport. Each of the compartments could be converted into sleeping mode, with four berths each: two upper and two lower. Even the airplane’s windows were asymmetrical, with two closely located windows per compartment on the right side and a more traditional lineup of nine windows on the left. Only 10 Stratoliners were built, five for TWA, three for Pan Am, and, a single ship for private use by Howard Hughes, then the owner of TWA. The prototype was lost early on and this delayed the entry into service which eventually took place in 1940. Within two years they went to war but most came back into civil service in 1945. TWA then used a more traditional cabin layout of 38 seats. Only one airframe, NC19903, survives, a former Pan Am aircraft preserved in flying condition at the National Air & Space Museum’s Udvar-Hazy Center adjacent to Washington-Dulles (IAD) airport. The hull of the Howard Hughes aircraft was converted years ago into a private houseboat and is now in the collection of the Florida Air Museum.

The unique cabin layout made for a unique way of seat numbers. I reproduce a cabin plan from a TWA ticket jacket, dating from about 1941. Left is forward. The numbering reflects the order of passenger comfort: the lowest numbers for compartment seats that could be converted into berths (1 to 17, with number 13 omitted), then the row of seats on the left (18-26), and finally the less popular middle seats in the four compartments (31-38). The first 16 numbers had the suffix U or L for upper or lower berth respectively. Note that in each compartment, the outboard seats were even-numbered and the inboard seats odd. The omission of the number 13 meant a reversal of the numbering direction in the fourth compartment.

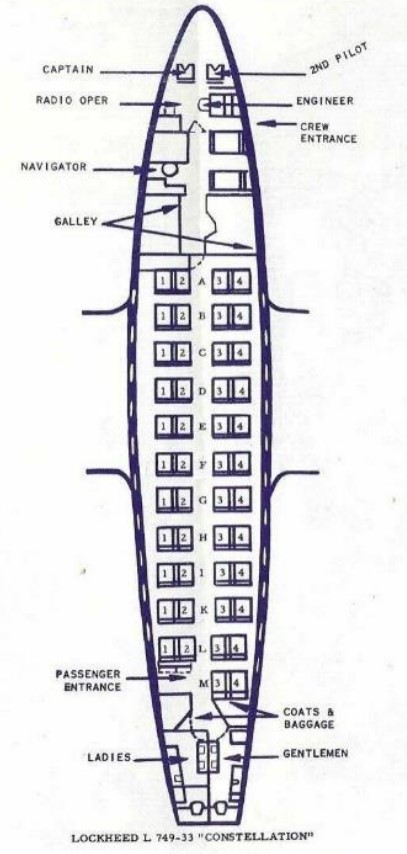

The practice of sequentially numbering all seats in airplane cabins continued after the war. In the second half of the 1940s, KLM used airplanes much larger than the DC-3, with seating capacities of up to 46. I show a Lockheed L-749 Constellation seat plan dating from a flight in September 1949. KLM still listed all the passenger names and destinations and distributed this to all on board.

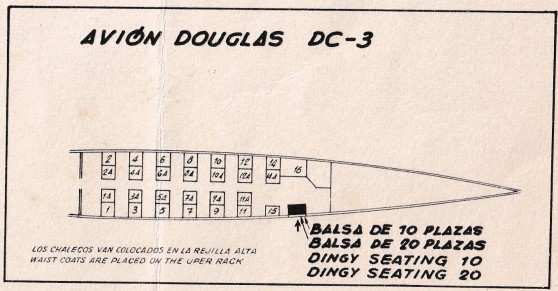

With so many seats, it became difficult for the crew to remember their numbers when directing passengers to their seats. Iberia thought of a way to make this easier. They came up with odd numbers on the left side and even numbers on the right side. This was for window seats. For aisle seats, an A was added. The number 13 was omitted. This diagram is taken from their safety leaflet and also shows the location of the life raft, or “dingy” as it was translated by Iberia.

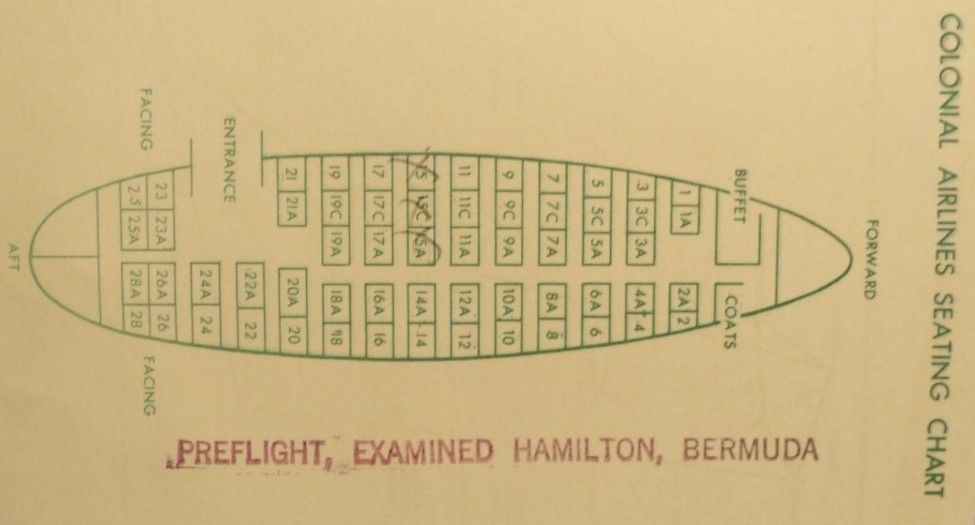

The same numbering method was employed by Colonial Airlines, a New York La Guardia-based airline that primarily flew between the Northeast USA and adjacent parts of Canada, but also had two overseas routes: from New York and Washington to Bermuda. On those routes, they used the DC-4, for which the seating chart is shown below. Being five abreast, center seats were added, marked with a C. You may wonder whether the illustrator actually saw the airplane or had an egg-inspired mental picture of how it looked like.

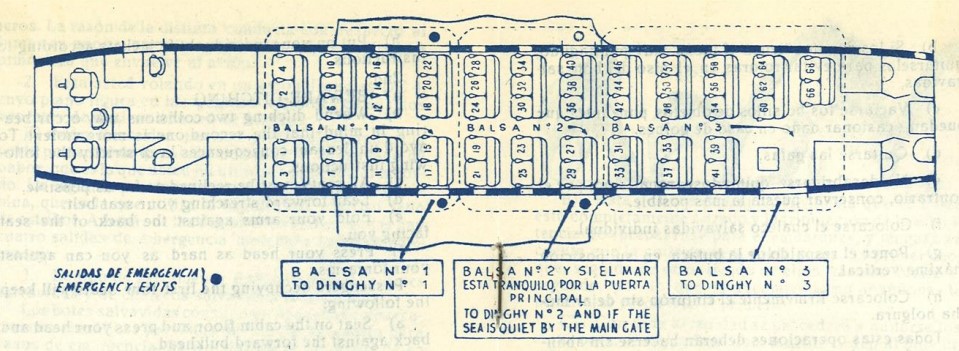

Iberia was apparently not entirely happy with their DC-3 numbering method. For the DC-4 they kept the left/odd and right/even style but discarded the letter A for the aisle seat and used numbers throughout. With more seats right of the aisle than left, this led to a situation where the numbers across the aisle progressively went out of sequence. As an example, the row with seats 39 and 41 on the left had seats 54, 56, and 58 on the right.

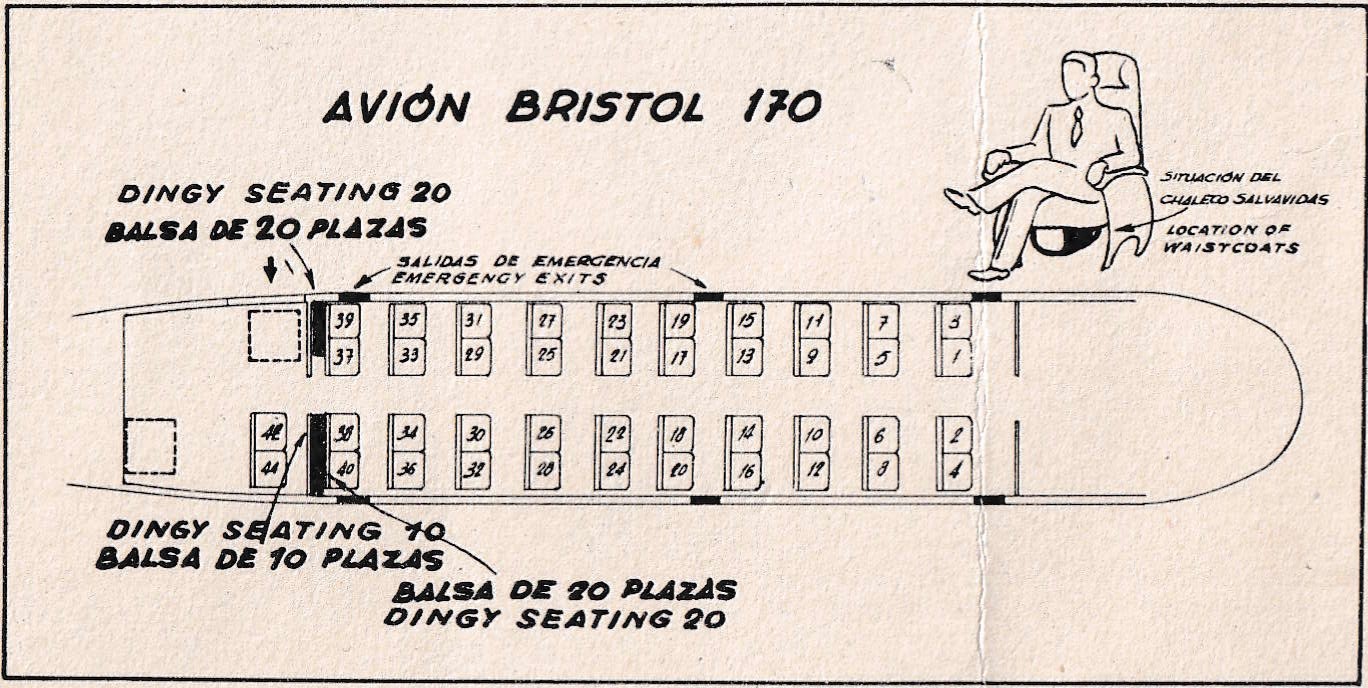

On their Bristol 170s, which were symmetrical in seating, this worked out better. The nose is right.

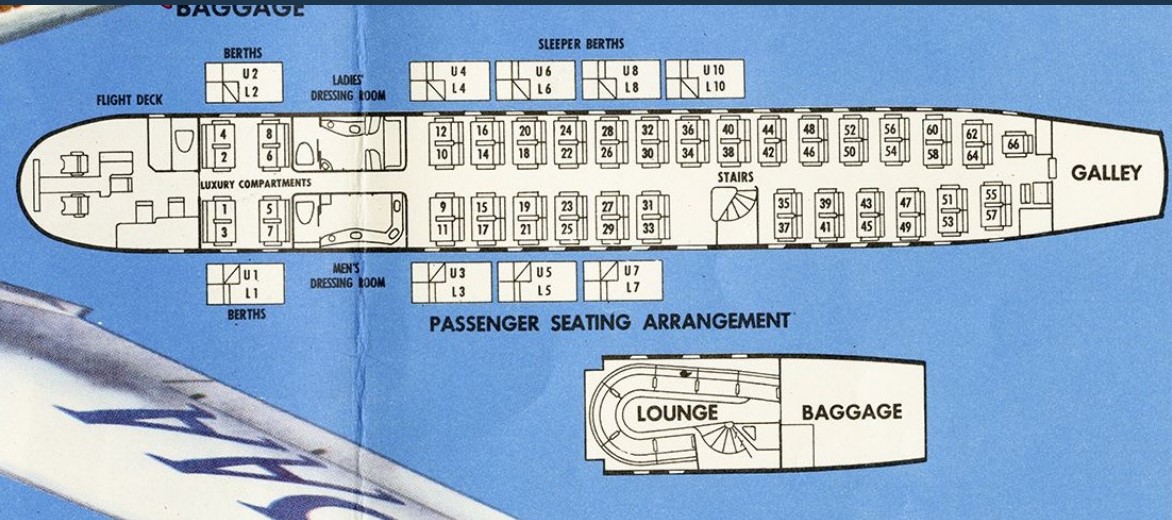

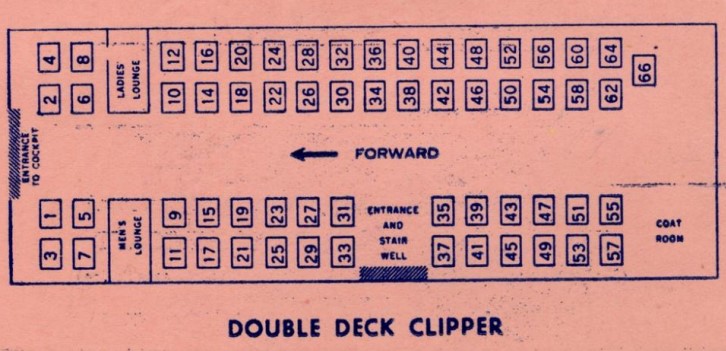

Pan American World Airways used the same method in their Boeing 377 Stratocruiser, which entered service in 1949. With equal numbers of seats on either side of the aisle, the numbering kept pace except for the aft section where there were no seats on the left in the boarding area. The layout also shows how the beds were numbered: U1 to U10 and L1 to L10. There was no U9 or L9.

On their boarding cards, Pan Am used a simplified presentation of the seat numbers, with a disproportionally wide aisle. “Double deck” referred to the lower deck lounge. This was not for use during take-off and landing, so its seats were not assigned and therefore remained unnumbered.

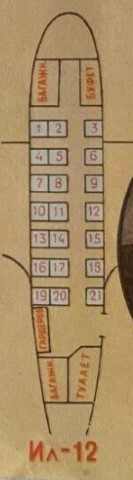

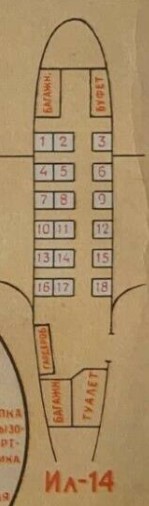

In the Soviet Union, Aeroflot applied the sequential numbering style on the Ilyushin Il-12 and Il-14. Note that the IL-12 has one more row than the IL-14, even though it is the smaller of the two types. The three-abreast layout shown here in a 1956 brochure was quite comfortable, as both types could seat up to 32 passengers in a four-abreast arrangement.

Aeroflot brochure extracts, 1956.

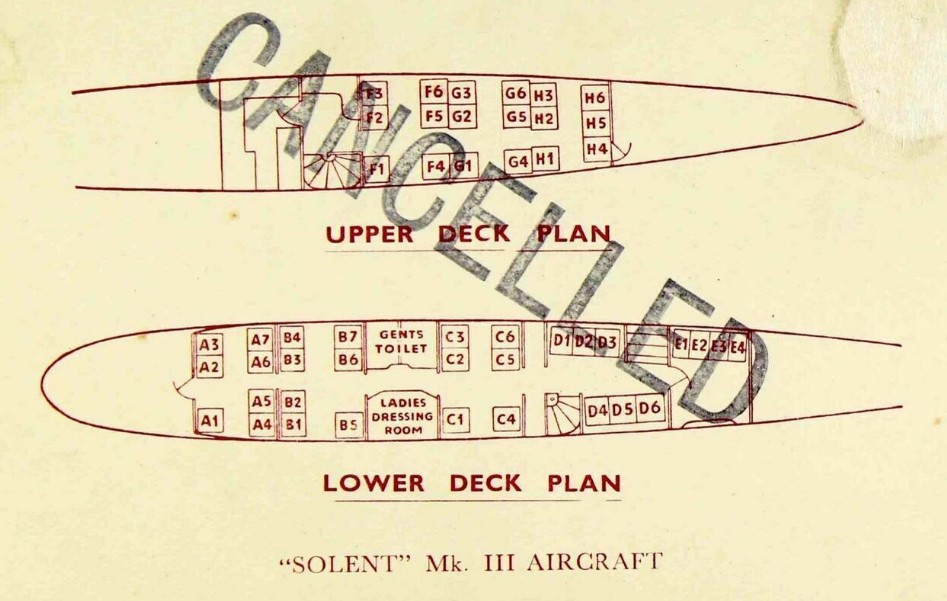

In the 1940s and 1950s, several air services were performed with flying boats, in most cases of the Short Brothers & Harland make, a Northern Ireland company. The design of the boats was such that it lent itself ideally to cabin compartments. I reproduce two samples: a Solent and a Sandringham.

The Solent was used by Aquila Airways in the 1950s between Southampton, Madeira, and the Canary Islands. It had eight compartments, identified from front to rear, main deck to upper deck as A to H. Within each compartment seats were numbered from left to right, front to rear. An exception was compartment D which had seats facing sideways and called for a different way of numbering.

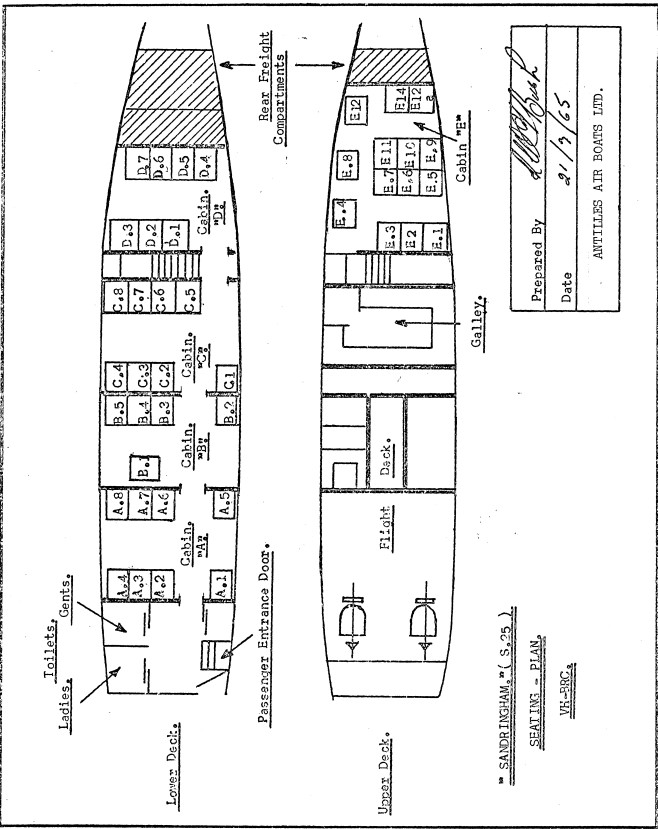

In the 1950s Short Sandringhams, operated by TEAL of New Zealand and Australia’s Qantas, crossed the Tasman Sea between these two countries. Ansett Airlines used them to operate to such remote islands as Lord Howe Island. After many years, two of the Ansett’s went to Antilles Air Boats (AAB) of St Croix, US Virgin Islands. In 1976 and 1977, one came to England for some pleasure flights off Poole and Calshot, near Bournemouth and Southampton respectively (I was lucky enough to be on one of those). That Sandringham is now preserved in the Southampton Solent Sky Museum, in Ansett livery. There is a nice website with many details of the AAB operation (antillesairboats.com), including an Operations Manual (from which I copied the seating plan). It is dated 1965 so must have been drafted by Ansett, in spite of having AAB’s name on it. The seat numbering resembles Aquila’s: letters for compartments and numbers within each compartment. Note that there was a seat E.12a, but no E.13.

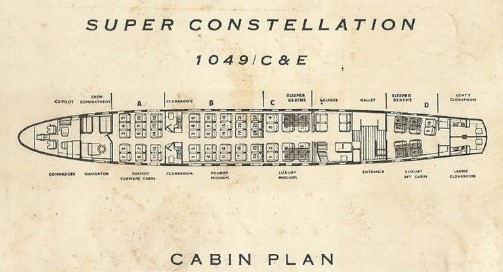

On land aircraft, compartments were also used and identified by letter for seat allocation purposes. An example is Air India, with its Lockheed Super Constellation, in service from 1954. Compartment identification started at the front. Within each compartment, numbers went from left to right, front to rear. Note that the economy class compartments were the first two (A and B), with the latter two (C and D) being first class with sleeper accommodation.

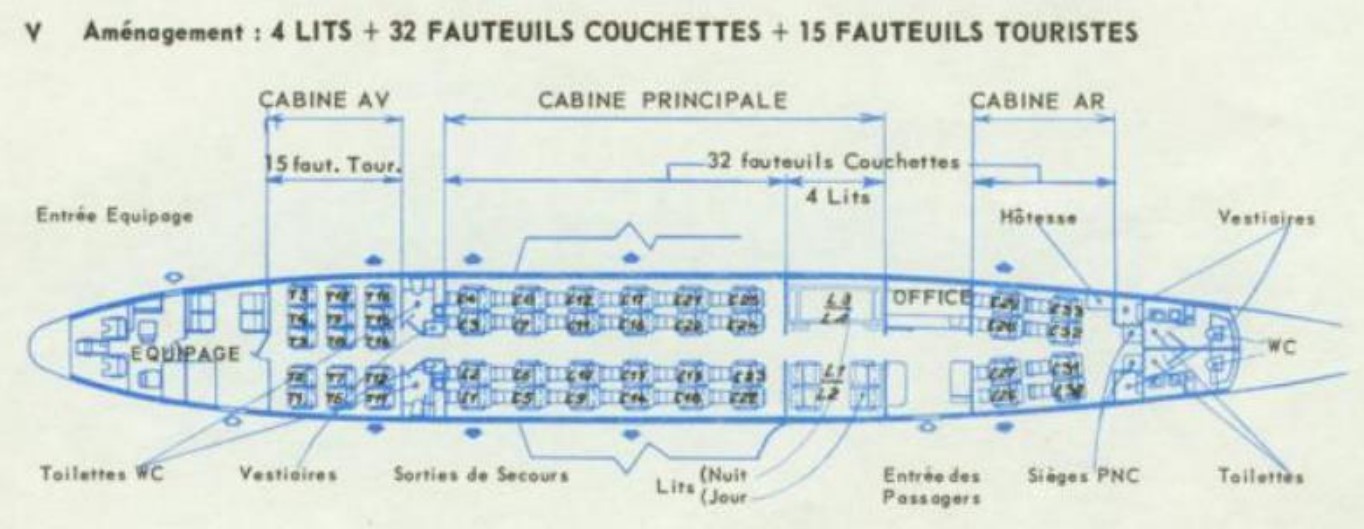

Another way of assigning compartments and seats was by class. On their Super Constellations, Air France employed a variety of layouts. I show the 15 tourist/32 couchette/4 beds layout.

The tourist class seats had the letter T followed by a number. Similarly, couchette seats and the beds started with a C and L (bed = lit in French), respectively. Couchettes were seats that reclined to allow sleeping but were not as comfortable as the beds.

So many different ways of designating seats must have been confusing. With capacities increasing, airlines needed a way to bring more structure to matters. The solution existed in the grid pattern that each and every cabin presented. It only needed people to recognize it. The typical grid layout of airplane cabins was that of multiple rows along the length of the cabin and seats lined up in each row. A simple system of coordinates solved the seat designation puzzle. Two solutions evolved:

In both cases, a combination of letters and numbers. This is generally known as an alphanumeric presentation. While this describes well the first solution, I propose using a new word for the second solution to distinguish it from the first and reflect the order of numbers before letters: “numeric-alpha.”

The earliest use of the alphanumeric method that I found was by KLM in 1950. The Lockheed Constellation plan that, ,as we saw earlier, in 1949 only showed numbers now has rows identified from A to M (row J omitted) with the seats across numbered 1 to 4.

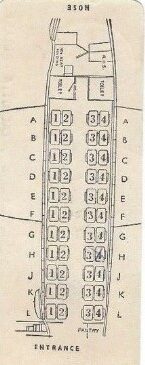

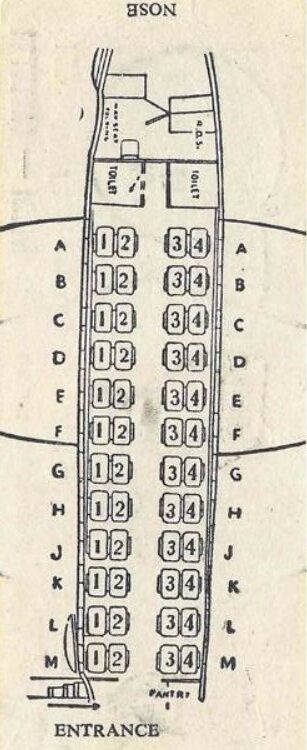

The alphanumeric method was used by other airlines in the same decade as well, including BOAC, Indian Airlines, and Qantas. In most cases, the letters started at the front, but in at least one case (the Qantas Lockheed Electra II) it went from rear to front. The lettering followed the common alphabet (ABC) and, with 19 rows being the maximum of the period, reached the S in BOAC’s Britannia high-density layout. The numbering in all cases started on the left with 1, reaching 4, 5 or 6 on the right. I assume that BOAC’s Comet 4 (which started jet air transport in the Western world on October 4, 1958) had the same numbering method, but could not find evidence. Neither could I find anything about the 1952 Comet 1 cabin layout. I would very much appreciate hearing from readers if they have a numbered seat plan for the Comet 1.

Indian Airlines’ reverse sides of boarding cards for the Vickers Viscount 700 series show its characteristic forward opening, circular doors. The undated image on the left shows 44 seats and likely dates to 1957, the year it entered service. The one on the right is from a later date and has 48 seats.

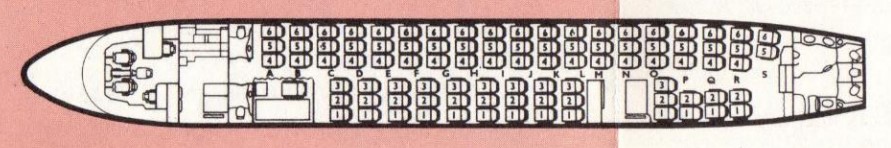

The earliest application I found of the numeric-alpha method was by United Airlines on their Boeing 377. This airplane type entered service in January 1950. This may well be the year United introduced this numbering system. A decade later it would become the world standard, but would they have realized that in 1950?

I found the seating diagram as it appeared on a period ticket envelope.

Other early users of the numeric-alpha method were TWA (now standing for Trans World Airways) in 1954 on their Lockheed Constellations, Eastern Airlines, also on the Constellation, and, quite surprisingly, the Soviet Union airline, Aeroflot.

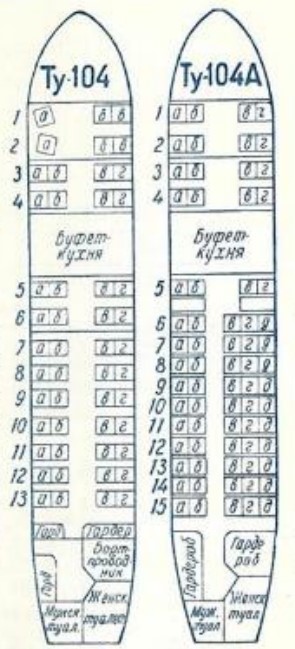

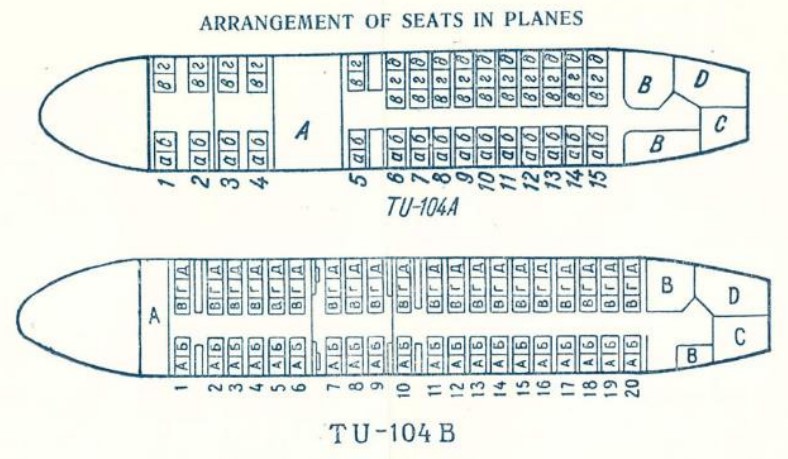

In 1956 Aeroflot introduced jet service and adopted the numeric-alpha way of seat numbering. The alpha element was in the Cyrillic script (aбв). I reproduce, from their winter 1957/58 timetable, the layouts of the Tupolev 104 (50 seats) and the improved Tupolev 104A (70 seats).

The inferior -104 model was quickly taken out of service and replaced by a second upgrade, as reflected in the summer 1959 timetable which shows the new 100-seat Tupolev 104B next to the Tu-104A.

More numeric-alpha examples, as well as non-conforming seat designations in the second (and final) part.

For this part, I used a variety of sources, including

Fons Schaefers

f.schaefers@planet.nl

April 2023

Airliners International 2023,American Airlines,Amon Carter Field,Dallas,Delta Air Lines,DFW,Fort Worth,GSW,Love Field,Meacham Field,postcard contest,Southwest Airlines

By Marvin G. Goldman

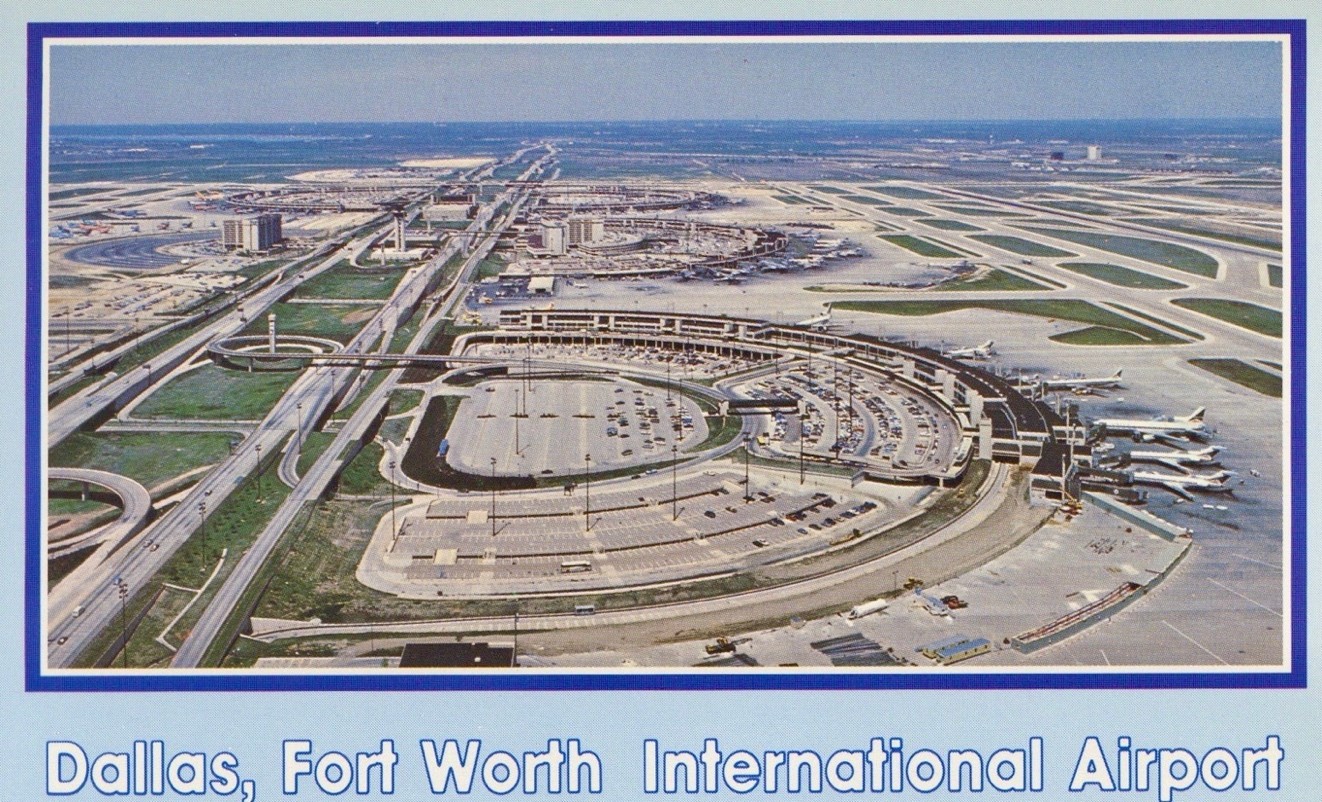

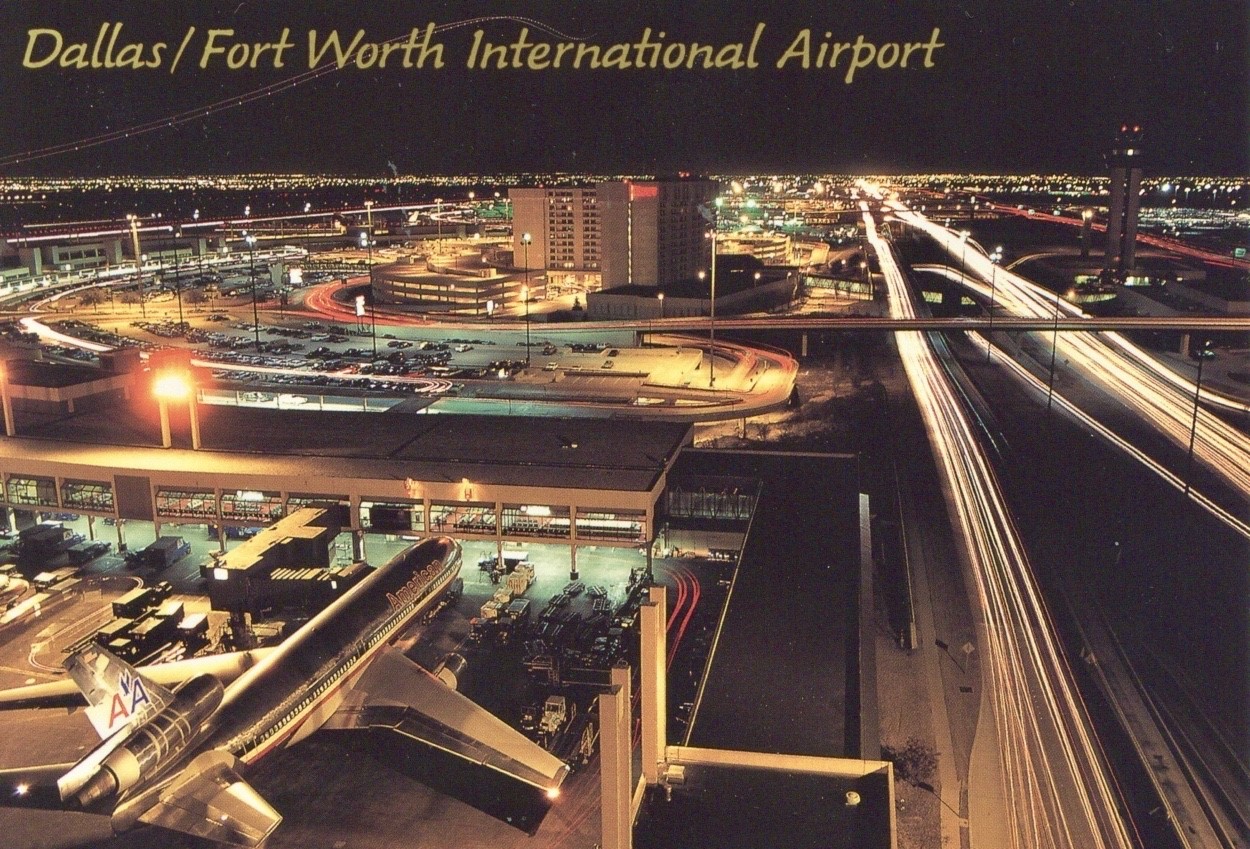

In view of Airliners InternationalTM, the world’s largest airline history convention and airline collectibles show, to be held June 21-24, 2023, at Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport (DFW), this Captain’s Log “Postcard Corner” article describes the background and development of the major airports in Dallas/Fort Worth, illustrated by historic postcards.

The large cities of Dallas and Fort Worth, Texas, are located only slightly more than 30 miles (50 km) apart. Economically, it made sense to develop one major airport to serve both cities. However, numerous proposals from the 1920s on for such a combination all came to naught until 1968 when, at the insistence of the U.S. Federal Aviation Agency (FAA), the two cities agreed to jointly build a single major airport to serve the area encompassing both Dallas and Fort Worth. That airport became Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport (DFW), located equidistant between Dallas and Fort Worth, and today the second-busiest airport in the world by passenger numbers.

Prior to the agreement to build DFW, Fort Worth and Dallas both competed to develop the dominant airport in the area for scheduled commercial flights.

In 1925 the City of Fort Worth purchased Barron Field, a World War I-era aviation training field, and named it “Fort Worth Municipal Airport.” In 1927 the airport was renamed Meacham Field after former Fort Worth Mayor Henry C. Meacham. American Airways (later to become American Airlines) established its base at Meacham Field in 1927, and the airport became the main airport for commercial airlines in the Fort Worth-Dallas area.

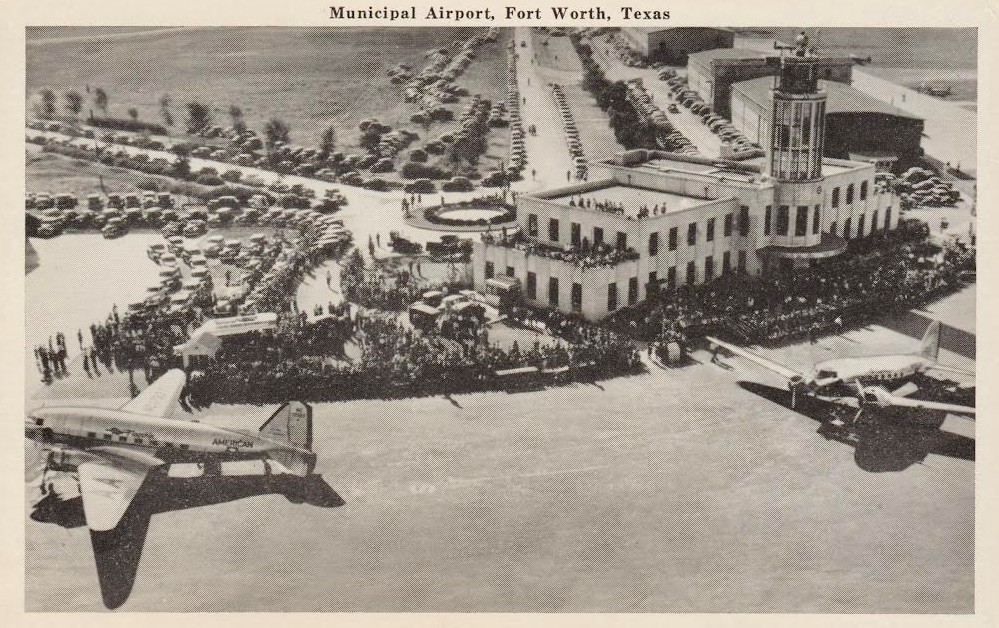

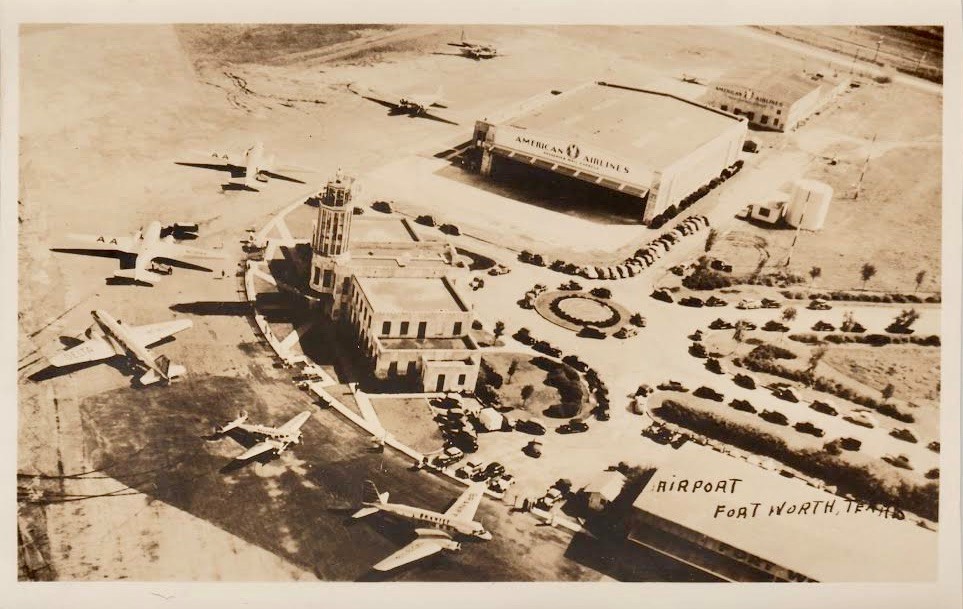

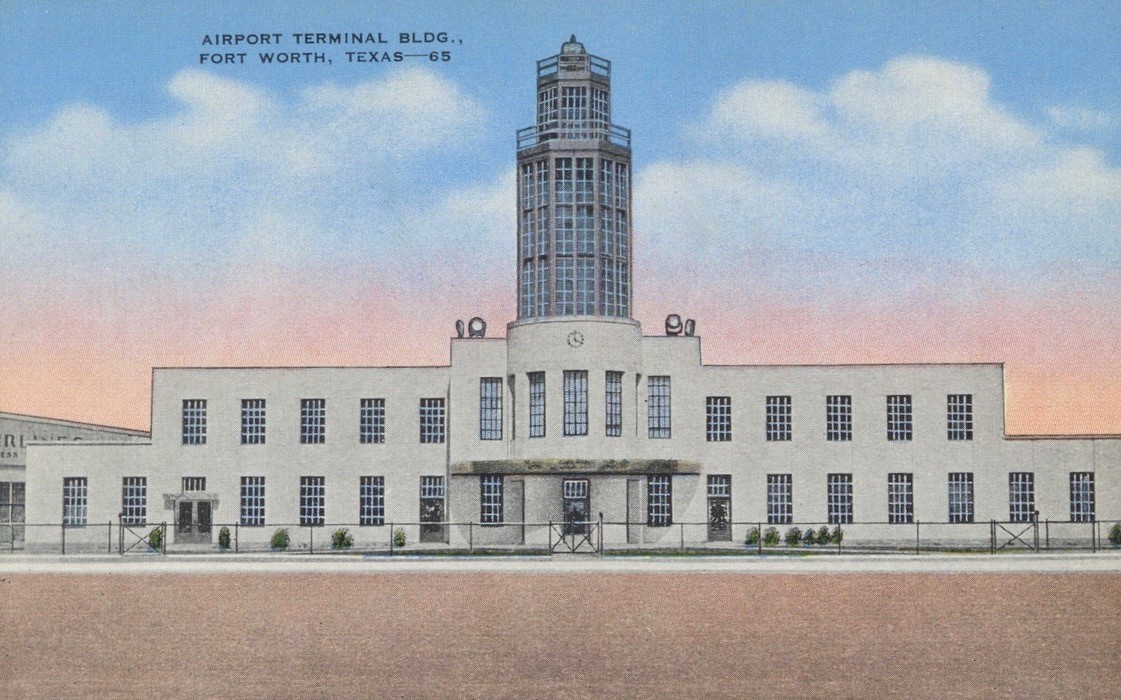

On April 4, 1937, Meacham Field dedicated a new terminal and control tower. The terminal was designed in the “Art Moderne” or new streamlined style, and it was the first air-conditioned passenger terminal in the U.S. Here is a selection of postcards showing Meacham Field and its new terminal.

During the early 1940s, Fort Worth decided to develop a larger airport to handle rising air traffic and allow future expansion that was not possible at Meacham Field. The site selected for reconstruction was that of Arlington Municipal Airport. It was located at the eastern edge of Fort Worth and was almost equidistant between the centers of Fort Worth and Dallas. Fort Worth invited Dallas to jointly develop the site to serve both cities. However, as Dallas was developing its close-in airport Love Field and that airport was preferred by its residents, Dallas declined to participate. Ironically, this new Fort Worth site was located almost adjacent to what later became today’s Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport.

The new Fort Worth airport finally opened on April 25, 1953, and was named Greater Fort Worth International Airport at Amon Carter Field (Amon Carter was the Mayor of Fort Worth). Airlines then transferred from Meacham Field to the new airport, Since 1953, Meacham has been used by corporate aircraft, commuter flights, and for student pilot training.

In 1962 Fort Worth changed the name of its new airport to “Greater Southwest International Airport” as part of an effort to again entice the city of Dallas to join in further development of the airport. However, that overture was turned down as well.

Here are some postcards of Greater Fort Worth International Airport, also known as Amon Carter Field and, from 1962, as Greater Southwest International Airport.

While scheduled airline service and facilities at Fort Worth’s Meacham and then Amon Carter Fields grew relatively slowly, its neighboring larger city, Dallas, developed Love Field which grew faster because more passengers preferred its proximity to downtown Dallas.

Love Field originated in 1917 as the site of an aviation training base established by the U.S. Army Air Service during World War I. It was named after Lieutenant Moses L. Love, an early Army pilot who was killed during flight training at another site. In 1927 the City of Dallas purchased Love Field from the military to serve as its site for commercial air service which developed during the 1930s. After the end of World War II in 1945, Love Field grew expansively, reflecting significant increases in passenger traffic. By 1965 Love Field featured new terminals and a second parallel runway, effectively doubling its capacity, and its passenger numbers that year were, astoundingly, nearly 50 times those of Fort Worth’s airport.

Here is a selection of postcards featuring Dallas Love Field.

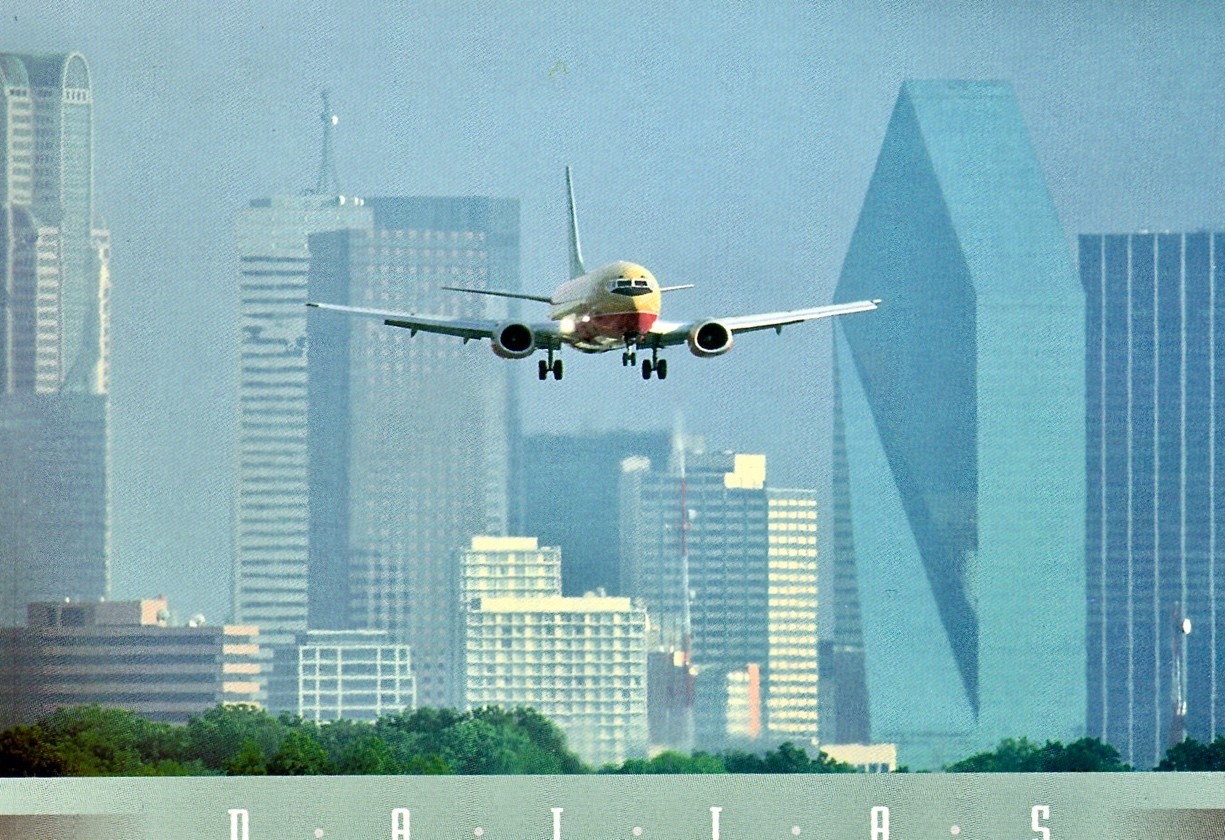

By 1965 Fort Worth’s Greater Southwest Airport at Amon Carter Field (GSW) was severely underutilized, while passengers and airline scheduled service flocked to Dallas Love Field which was bursting at the seams with air traffic and had insufficient room for expansion. The U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) decided it would no longer assist in funding improvements at two separate airports so close together. At the insistence of the FAA and the Civil Aeronautics Board, the two cities agreed to set aside their rivalry and jointly develop and operate a single larger and more modern airport equidistant between them. The agreement also provided that all airlines would have to move from GSW and Love Field to the new airport. The site chosen was a huge swath of undeveloped land just north of the Greater Southwest Airport. This is the site that became Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport – DFW. Ground was broken for the construction of DFW airport in 1968, and scheduled flights at DFW commenced on January 13, 1974.

Meanwhile, passenger traffic continued to sharply decline at GSW, and by 1969 all scheduled flights there had ceased. GSW continued in use for general aviation, some charter flights, commuter and air taxi traffic, and crew training, while also serving as a diversionary airport for Love Field. However, upon the opening of DFW in January 1974, GSW was closed. In 1979 GSW was sold for redevelopment as an industrial and office park, and its airport facilities were soon demolished. Today the headquarters of American Airlines’ parent company, AMR Corporation, is located where GSW’s terminal once stood, and American Airlines’ C. R. Smith Museum is opposite the GSW site.

Love Field continued its prominence while DFW was under construction. However, when DFW opened in 1974, all airlines – with one notable exception – moved their operations to DFW. The exception was Southwest Airlines which refused to move and prevailed on that issue in a lawsuit brought by the cities of Dallas and Fort Worth and the DFW Airport Board. Subsequently, Southwest fought several legal battles to lift restrictions imposed by the “Wright Amendment” on its ability to fly to destinations outside Texas. Full success was achieved in 2006 by a federal law that served to repeal the Wright restrictions. Since then, Southwest has financed several expansions of its facilities at Love Field, and it remains the dominant airline by far at Love Field. Other airlines currently operating scheduled flights there include Alaska Airlines and Delta Air Lines.

As mentioned above, DFW Airport opened to scheduled airline service on January 13, 1974, and all airlines except Southwest moved there from Love Field. With 27 square miles of land, DFW is the second largest airport in the U.S. by area (next to Denver); and with 72 million passengers in 2022, it is the second busiest airport in the world by passenger numbers (behind Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport – ATL). Presently, 28 airlines serve a total of about 260 destinations from DFW.

Commensurate with its growth in passenger numbers, DFW airport is continuously expanding its facilities. Most recently, DFW approved in 2021 a $2 billion project, to be completed by 2026, including the renovation and expansion of Terminal C serving American Airlines and the addition of gates at other terminals.

Here is a sampling of postcards showing DFW.

All the postcards shown in this article are from the author’s collection unless otherwise noted. My estimate of rarity: Rare: the two aerial views of Meacham Field; Uncommon; American Airlines at Meacham Field; Love Field with Trans-Texas and American aircraft; Love Field with Continental Viscount; and DFW Braniff terminal. The rest are fairly common.

I hope to see you at Airliners International™ 2023 DFW, June 21-24, 2023, at the Hyatt Regency Hotel, next to Terminal C at Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport. This is the world’s largest airline history and airline collectibles show and convention, with more than 200 vendor tables for buying, selling, and swapping airline memorabilia (including, of course, airline and airport postcards), seminars, the annual meeting of the World Airline Historical Society, annual banquet, tours and more.

I hope you’ll consider entering the Postcard Contest at the AI 2023 show. More information and contest rules are available by clicking this link: airlinersinternational.org.

Until then, Happy collecting. Marvin

Safety cards

By Fons Schaefers

Pioneers

Until the early 1960s survivability of transport aircraft accidents was not an issue. The attitude towards accidents was that they were a fact of life. All funds for safety should be allotted to learning from them so as to prevent future accidents. Investigations focused on the causes of accidents, not on their consequences in terms of survivability. It took two pioneers a decade or more to teach the aviation world it was worthwhile to expand the focus to survival factors, also known as “passive safety.” They proved that many improvements could be made in making aircraft more crash-worthy.

Those pioneers were Hugh DeHaven (1895-1980) and Howard Hasbrook (1913-2000). In 1942, DeHaven started the crash injury project at Cornell University (New York). In 1953, this was split into an automobile section, which he further developed (and which inspired car safety belts and Ralph Nader’s “unsafe at any speed”), and an aviation section. The latter was run by Hasbrook, who in the 1950s and early 1960s did pioneering work in investigating survival factors of major aircraft accidents. One of his earliest investigations was that of the National Airlines DC-6 crash near Newark in February 1952. He was the first to make sketches of the crash kinematics illustrating how and why aircraft broke up. Curious? Then go to https://archive.org/details/dtic_AD0030398/mode/2up

Not only were his methods innovative and his findings unprecedented but he also spent much time and effort in advocating them to airframe manufacturers, airlines, and aviation authorities, not only in the US but also abroad. His recommendations were well ahead of their time. Already in 1952, he suggested passenger seats be tested dynamically. It would take more than four decades before this became mandatory, first in the USA and later worldwide.

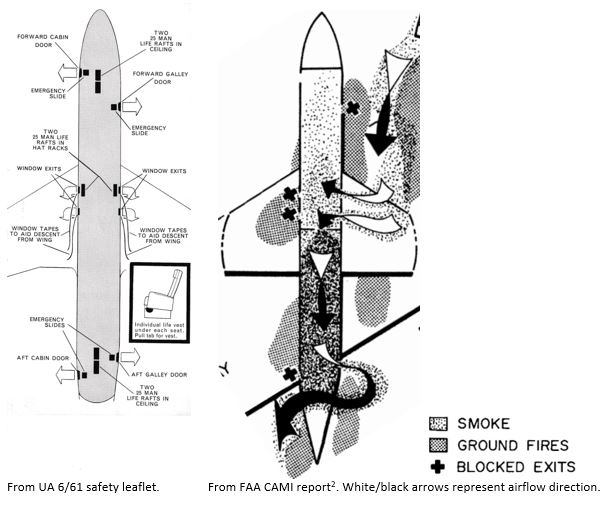

His safety campaign was successful. In 1963, the FAA proposed rulemaking for a host of cabin safety measures, ranging from improved exit signs and markings to mandatory evacuation demonstrations by airlines, and passenger briefings. Of course, it was not only Hasbrook who triggered the FAA to come into action. Less than three years after the first jets entered service in the US, the first crash of a jet with survivability issues happened: a United Airlines DC-8 at Stapleton Airport in Denver, CO, on July 11, 1961. Hasbrook investigated the circumstances in the cabin, which were painfully shocking [1]. To understand what follows, I reproduce the exit plan of United’s safety leaflet next to a sketch of the accident’s wind-steered smoke and fire pattern. The safety leaflet is dated 6/61, so released just weeks before the crash.

[1] FAA CAMI AM 62-9, Evacuation pattern analysis of a survivable commercial aircraft crash

The crash itself was mild, but a fuel fire erupted, gradually entering the cabin. All passengers in the first class section, which was large and extended from the front back to the wing and included all four overwing exits, survived. In the tourist class section, however, 16 passengers died of smoke inhalation. In that section, there were only two exits, only one that could be opened. The aisle was narrow and the divider between the two classes reached from floor to ceiling, obscuring the view forward. There was no indication, such as a sign, that there were exits beyond it. No passenger briefing had been given, even not after it had become clear that the landing would not be normal.

Whether the tourist passengers had boarded aft and were thus unaware of the forward section and the exits there, is not reported but it would not surprise me.

This accident was the first of a jet that should have been survivable to all occupants. It provoked a lot of attention. Four months later, a survivable, yet fatal accident occurred with a Lockheed Constellation on a military charter with young army recruits, many of whom died. That accident got much less attention for reasons unknown. In any case, the time was ripe for improved cabin safety measures. Something had to be done to increase the chances of passengers who survive the impact to escape from an aircraft before a fire overtakes them. The Federal Aviation Agency (FAA) came into action and, as said, in 1963 proposed a plethora of new cabin safety regulations. [3]

[2] FAA CAMI AM 70-16, Survival in emergency escape from passenger aircraft

[3]NPRM 63-42, Federal Register October 29, 1963

1965 – First Safety Card Rule

Although in 1962 Hasbrook recommended passengers be instructed in evacuation procedures prior to “any anticipated, unusual landing situation,” he did not go as far as asking for safety cards. Neither, in 1963, did the FAA. But, at a hearing in June 1964 on the proposed regulations, somebody suggested safety cards as an additional measure. By whom, I could not find, but I would not be surprised if it was one of those operators already voluntarily using them. United Airlines, perhaps?

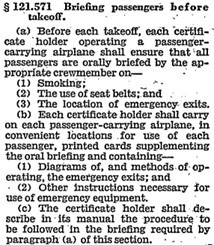

When the final rule was issued in March 1965, the FAA mandated printed safety cards for all US airlines per June 7, 1965. Here is the text of the regulation – focus on section (b):

As you can see, the requirements for the card were simple. They must show:

These requirements were broadly worded. The first was generally interpreted as showing the location of the exits on an airplane plan. The second was met by illustrating how to open the exit. The third one was quite vague – does this include emergency equipment like fire extinguishers or first-aid kits? Not so if we look at the safety cards of the time. They showed oxygen masks, escape slides and for overwater operations, life vests and, occasionally, life rafts, but nothing more.

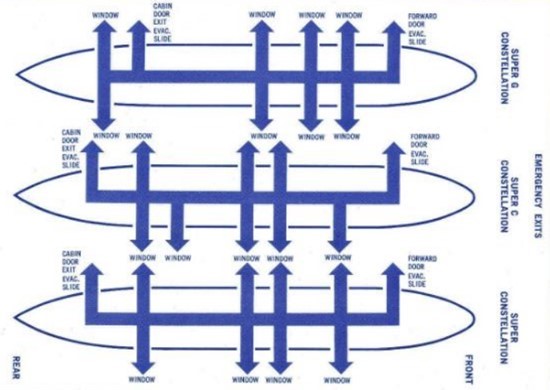

1965 Safety Cards

The new rule must have triggered several US airlines to issue a new range of safety cards. I will discuss some that directly resulted from it and some that were simply continuations of what was already there. Eastern Airlines issued new cards immediately, in June 1965. Eastern was one of the airlines that had separate cards for each aircraft type, as opposed to fleet cards. For an example see the DC-7 card in Lester Andersons’s July 2020 contribution below. Eastern’s Constellation card was a bit hybrid, as it showed three variants, each having a different exit layout. I reproduce the trio here, rotated 90 degrees to allow easier reading of the exit captions.

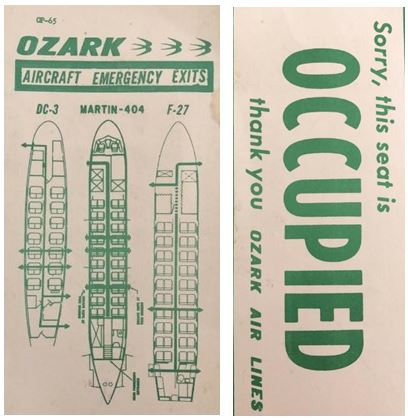

Ozark Air Lines had a fleet card labeled “OP-65,” which may have been in response to the new rule. It showed exit locations for three aircraft types: DC-3, Martin 404, and Fairchild F-27. This mix indeed uniquely reflects their 1965 fleet composition so it was likely released that year. But other than exit locations, nothing else was shown so it did not fully meet the new rule. On the reverse side, it said “occupied” in large letters, for passengers to reserve their seats during transit stops.

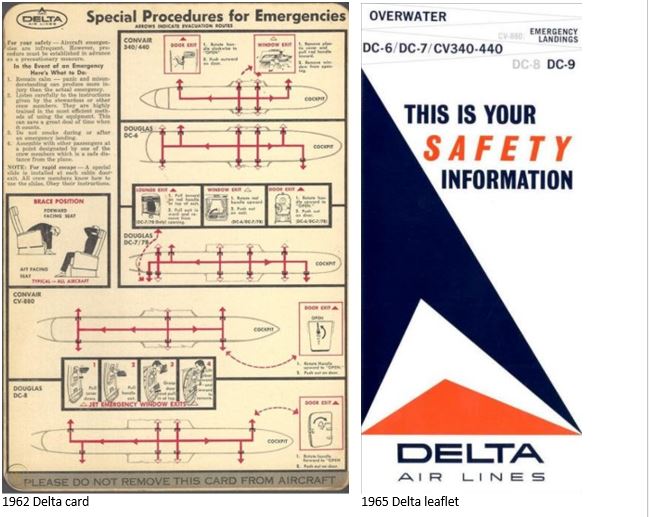

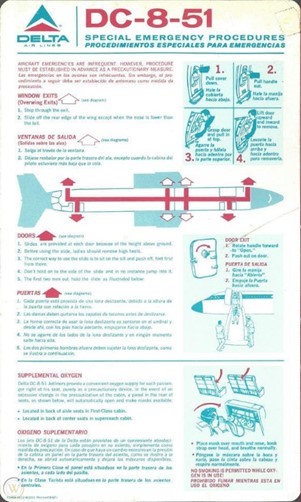

Delta Air Lines used fleet cards before the cabin safety card rule came into effect. I present the card used in the period 1962-1965, copied from the internet. It was called “Special Procedures for Emergencies.” This shows aircraft plans for the Convair 340/440, Douglas DC-6, DC-7/7B, DC-8, and Convair 880. Note the cockpit is on the right. The emergency exits consisted of either doors or window exits and were well indicated, with the means of opening explained in small panels.

This card survived the June 1965 regulatory change, as it already met it.

The single card was replaced about six months later by a leaflet with four vertical folds, like an accordion. It was issued in conjunction with the introduction of the new DC-9. In appearance, it was a complete makeover. The rather technical presentation was gone and replaced by a more attractive and modern look, making optimum use of the Delta logo. Other than that, it featured the same types as the previous card. I reproduce the front, but see also Brian Barron’s July 2017 entry.

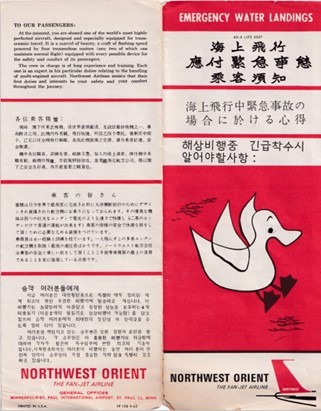

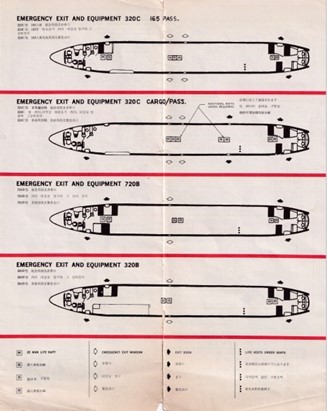

Northwest Orient Airlines renewed its leaflets in September 1965. Northwest re-issued the “emergency water landings” leaflet in use since the early 1950s. While it indeed included diagrams of four different types showing exit locations, it lacked the method of opening them. This would rate it as not meeting the new rule. However, Northwest, while continuing this line of overwater leaflets, augmented them with a separate leaflet explaining the automatic oxygen system, exit locations, and opening method. Thus they met the new rule. On that leaflet, the Boeing 727 was added to the overwater types, but not the Lockheed Electra and DC-7C. Apparently, separate cards were made for those, non-automatic oxygen-equipped types (see Lester Anderson, July 2020).

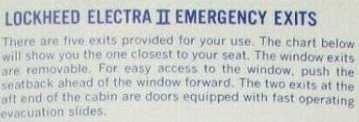

Western Airlines changed its cards in December 1965. They were fleet cards, showing three types on one leaflet: Boeing 720B, Lockheed Electra II, and Douglas DC-6B. It had airplane plans, exit operation method panels, and more. I reproduce the plan for the Electra as that has some interesting features, which could easily have led to passenger confusion:

1967 – First Amendment to the Safety Card Rule

I could not find any cards dated 1966. That year however stands out as it saw a proposal by the FAA for already modifying the new briefing card rule. Two new requirements were presented for public consultation, which the FAA believed would improve passenger knowledge and avoid confusion:

The first proposal met with resistance from the airlines and was not adopted. The second, however, was well received and took effect on October 24, 1967:

This meant the end of fleet cards, at least in the USA.

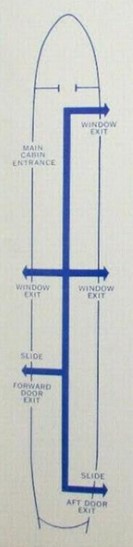

Delta responded quickly and first issued type-specific cards in September 1967, one month before the rule deadline. They diligently made separate cards for each type and model, as the new regulation stipulated: one each for the DC-9-14, DC-9-32, DC-8-33, DC-8-51 (shown), CV-880, etc.

Five years later (8/72), they joined the two short DC-8 models (DC-8-33 and DC-8-51) on one card, as the exit locations and method of operation were identical. Yet, on the cover, a different type appeared. Delta later corrected that.

1968 and 1969 Safety Cards

The revised regulation led to an abundance of cards. Like Delta, the major carriers, aware of the upcoming rule, had already started re-issuing their cards in 1967. Scroll below to the articles by Barron and Anderson in this Captain’s Log safety card section to see some examples.

The next two years saw many more airlines introducing or revising them. Let me reproduce a selection to illustrate the artwork and methods of presentation.

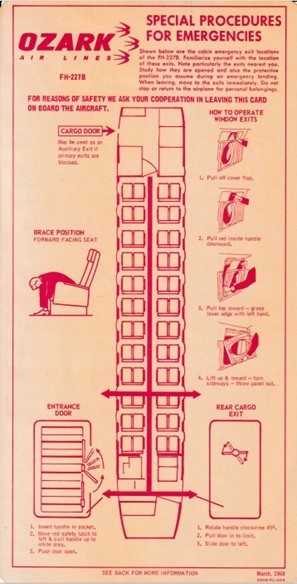

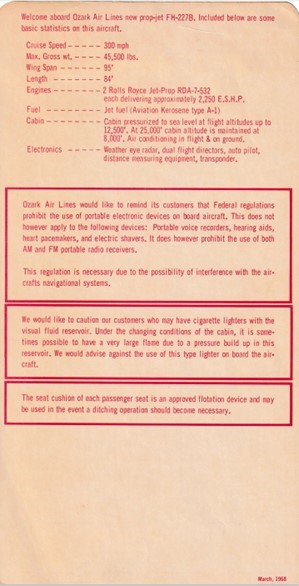

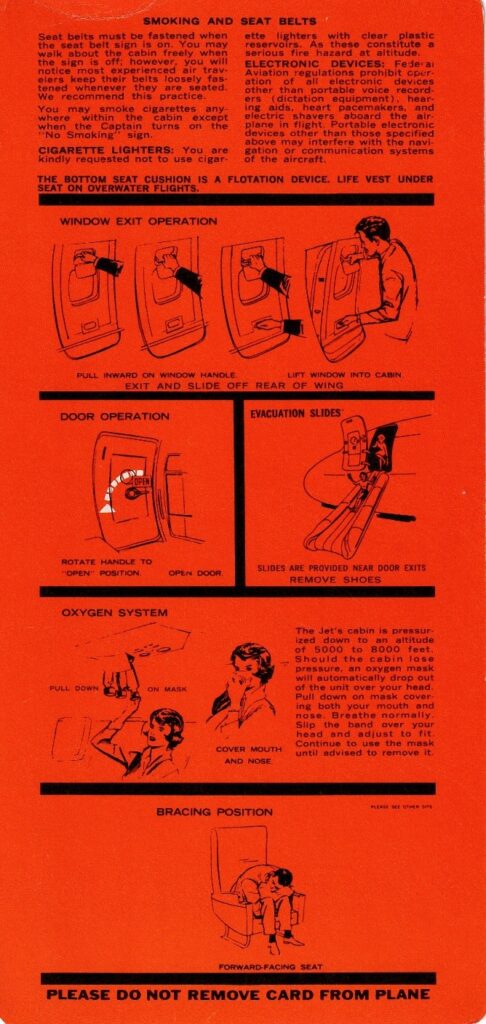

in March 1968, Ozark Air Lines issued this Fairchild FH-227B card. On one side it has some technical data, plus text cautions about electronic devices, lighters, and a notification about flotation cushions. On the reverse side, there is graphic safety information showing exit locations and their operation.

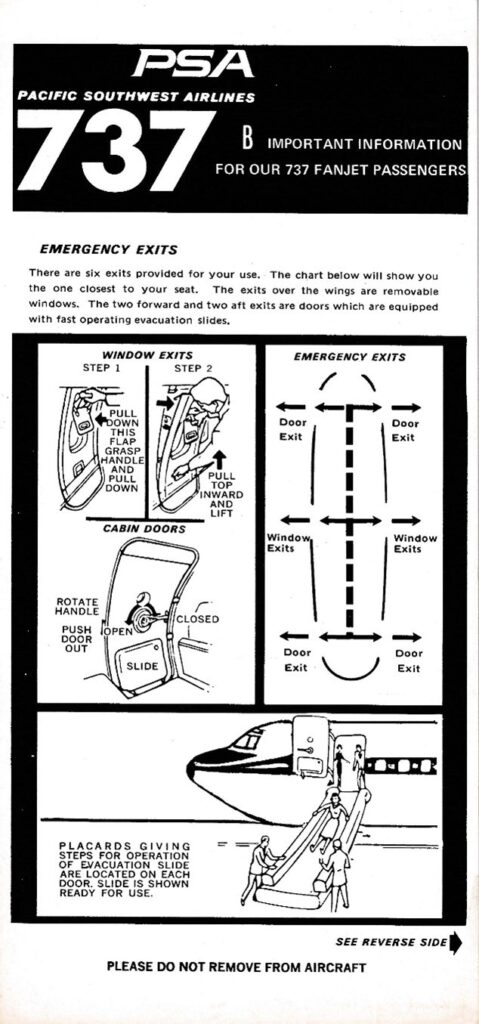

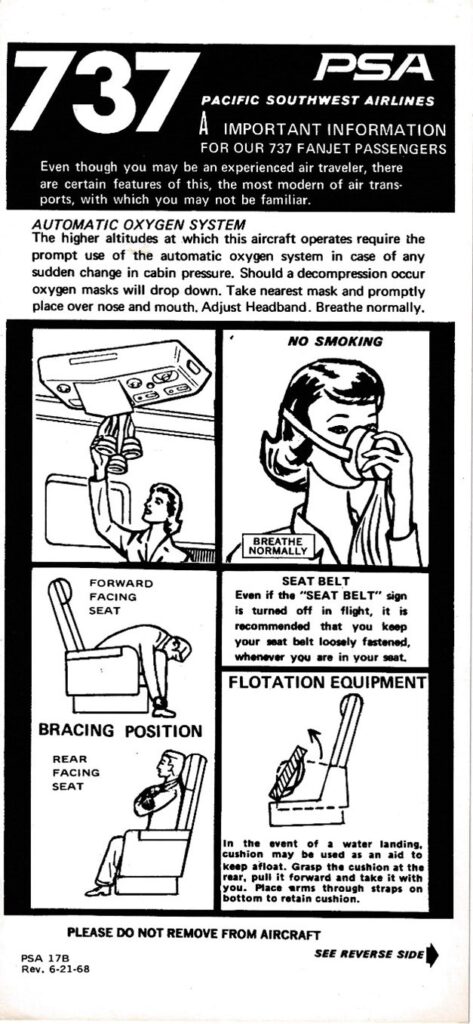

Pacific Southwest Airlines introduced the Boeing 737 in September 1968, a brand new aircraft type. They had the safety cards prepared well in advance, as evidenced by the issue date: June 21, 1968. Emergency exit location, operation, and the slide were shown on one side; oxygen, bracing position, and flotation equipment were on the other. Note the rather primitive way of portraying the cabin.

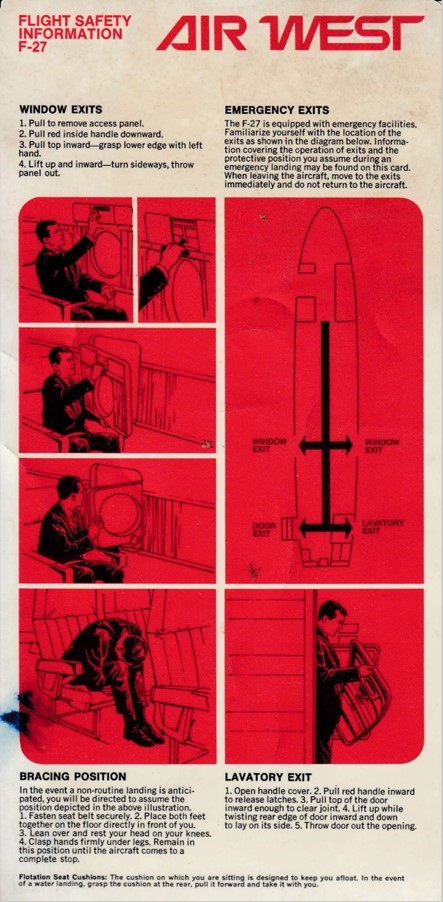

Air West was formed in April 1968 by a merger of Pacific Air Lines (which started in 1941 as Southwest Airways, not to be confused with the later Southwest Airlines), Bonanza Air Lines, and West Coast Airlines. They all operated the Fairchild F-27. Their operating area covered the eight westernmost United States, so the new name, Air West, was apt. Air West’s December 1968 card was identical on either side, but for the language: English on one side, Spanish on the other. Safety information was limited to bracing position, flotation seat cushions, exit locations, and operation of the window exits plus the exit in the lavatory. The F-27 (both as built by Fokker and Fairchild) was probably unique in that one exit could only be accessed via the lavatory! For that purpose, its door needed to be secured open during take-off and landing. How the oppositely located integral stair-equipped entrance door opened was not shown. The illustrations were black on red, which would not have helped in conditions of poor lighting. When former TWA-owner Howard Hughes bought Air West in 1970, it became Hughes Airwest. In 1980 it was bought by Republic Airlines, which itself was absorbed by Northwest Airlines in 1986, which, in turn, was acquired by Delta Air Lines in 2008.

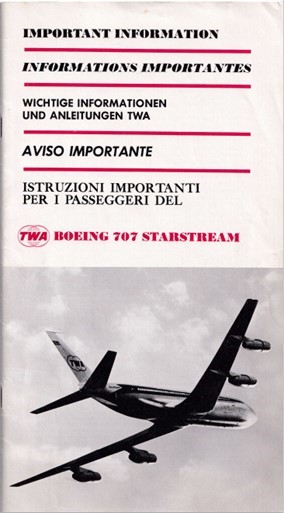

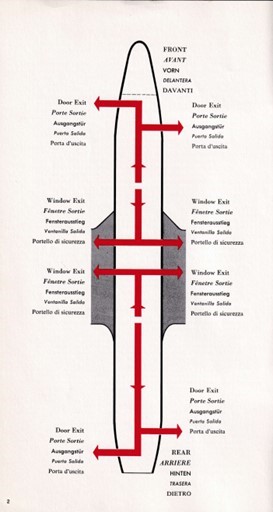

In February 1969, TWA issued an extensive 18-page booklet for their 707 “Starstream” in five European languages. Large in size and print, and well-illustrated, not only are exit locations and their operation explained as well as oxygen, life vests, and rafts, but also seat belts, smoking, and portable radios and TVs. It had separate pages for infant life vest use and even how rescue is organized. The exit plan shows internal escape routes which are confusing in the overwing exit area. The longitudinal arrow lines are not connected between the two pairs of overwing exits. Was there a barrier? No, actually, there were seats between these exits. Probably TWA wanted to stress the importance of the overwing exits for passengers seated in the center cabin and omitted this detail.

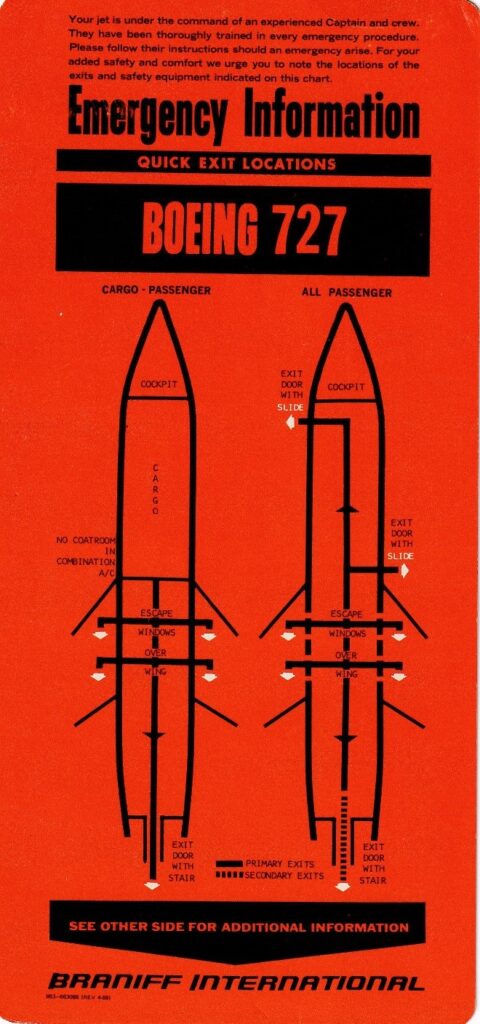

Braniff had much simpler cards, two sides only, with “quick exit locations” on one side and exit operation (plus smoking, seat belts, oxygen, and bracing opposition) on the other side. On the April 1969 card, two variants of the 727 are shown: “cargo-passenger” and “all passenger.” Would this meet the regulatory qualification for same type and model? The cargo-passenger version shows the cargo compartment forward of the wing. The only exits available for passengers are those over the wing plus the tail exit, which is ranked as a “primary exit.” For the all-passenger version, that exit is a “secondary exit.”

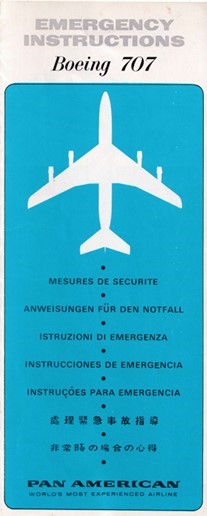

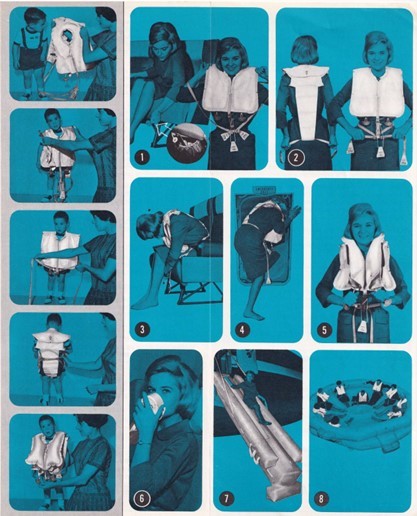

Like TWA, Pan American issued a booklet for their Boeing 707. It covered the same subjects as TWA did, but was smaller and in three more languages (Portuguese, Chinese, and Japanese). I reproduce from their July 1969 edition the front page and the illustration page. The latter folds out so it can be read along the subject page of the selection.

Outside the USA

The new rules directly affected US carriers. But they also inspired other countries to adopt the same, or similar regulations. I highlight three airlines from three European countries.

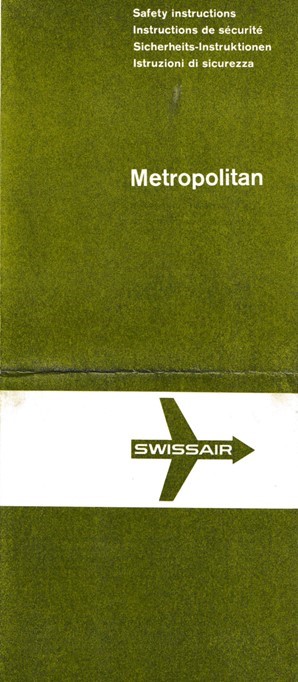

In Switzerland, Swissair replaced its fleet leaflets with type-specific leaflets around 1965, so actually before the US did. I show the type-specific leaflet for the Convair Metropolitan, the name that the Swiss used for the Convair 440. It is undated but I estimate it to be from around 1965.

Sometime in the 1950s, KLM of the Netherlands introduced a generic leaflet with emergency preparation instructions in six languages and included illustrated life vest instructions. Unfortunately, I do not have a copy to show. It was not a fleet card as it lacked type-specific information, like aircraft diagrams, but was likely used on all types. Exit information was limited to one line:

“The escape hatches are marked ‘Emergency exit’ and the method of opening them is clearly indicated.”

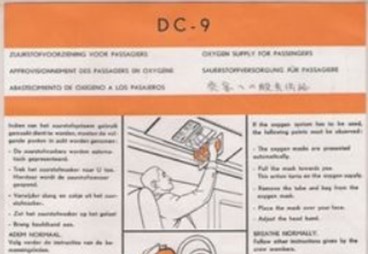

It must have been used well into the next decade. For the DC-8, DC-9 and “Super DC-8” (DC-8-63), introduced in 1960, 1966, and 1967 respectively, it was augmented with separate leaflets for oxygen use, in no fewer than 12 languages, reflecting KLM’s standing as a global airline serving passengers of many tongues. Here is a poor-quality internet reproduction of the top portion of the DC-9 oxygen card.

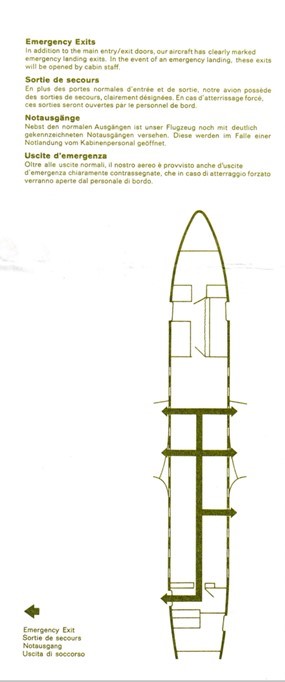

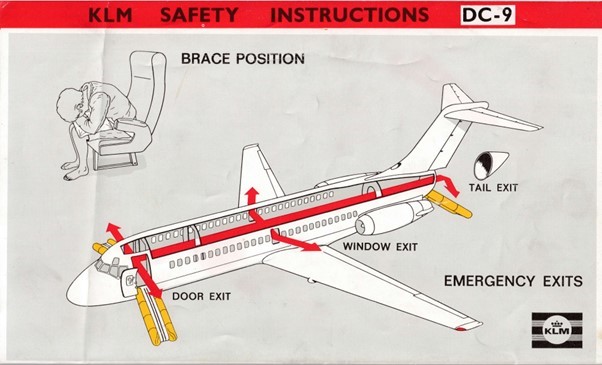

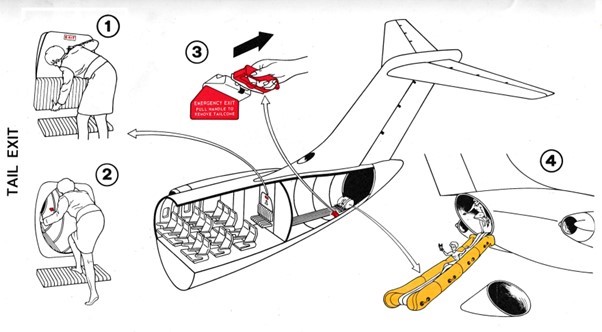

Later, and likely prompted by the developments in the USA, KLM replaced the generic leaflet and oxygen supplements by type-specific cards. That change was drastic. From nearly text-only, KLM went for a low-text, all-graphic presentation, quite possibly to avoid the burden of having to translate in so many different languages. The new cards showed exit locations and their operation plus the brace position, oxygen use, and life vests. None of the early cards had an issue date making it difficult to determine a year. My best guess is 1968. There were separate cards for two versions of the DC-8 as well as two versions of the DC-9, all uniquely coded. The DC-9 cards carried the striped KLM logo which lasted until 1972. The DC-8 cards did not have any logo, possibly because they regularly flew for partner airlines such as Garuda Indonesia and Viasa (Venezuela) and KLM wanted to avoid confusion on the part of the passengers. I reproduce two panels from the DC-9 series 10 card.

The UK was one of the few countries with a strong civil aviation industry and authority, which had its own agenda. It did not follow the US as closely as many other countries. Many of the cabin safety measures invented in the US took a long time before they landed in the UK. In Britain, the airlines presented passenger safety information in their traditional in-flight magazines until well into the 1970s without issuing separate cards. I show the 1968 example of British Eagle, one of the independent airlines of the time. On the front cover, there is a reference to the safety on board pages, in three languages. The instructions are extensive and clear, but in text only, except for pictures of life jacket use. Further down the magazine technical data appears for the airplane types, with exit diagrams. I reproduce those for the Britannia (top) and the abundantly-exited Viscount (bottom).

In the next part, I will review safety card developments in the 1970s and 1980s.

Fons Schaefers / January 2023

Email: f.schaefers@planet.nl

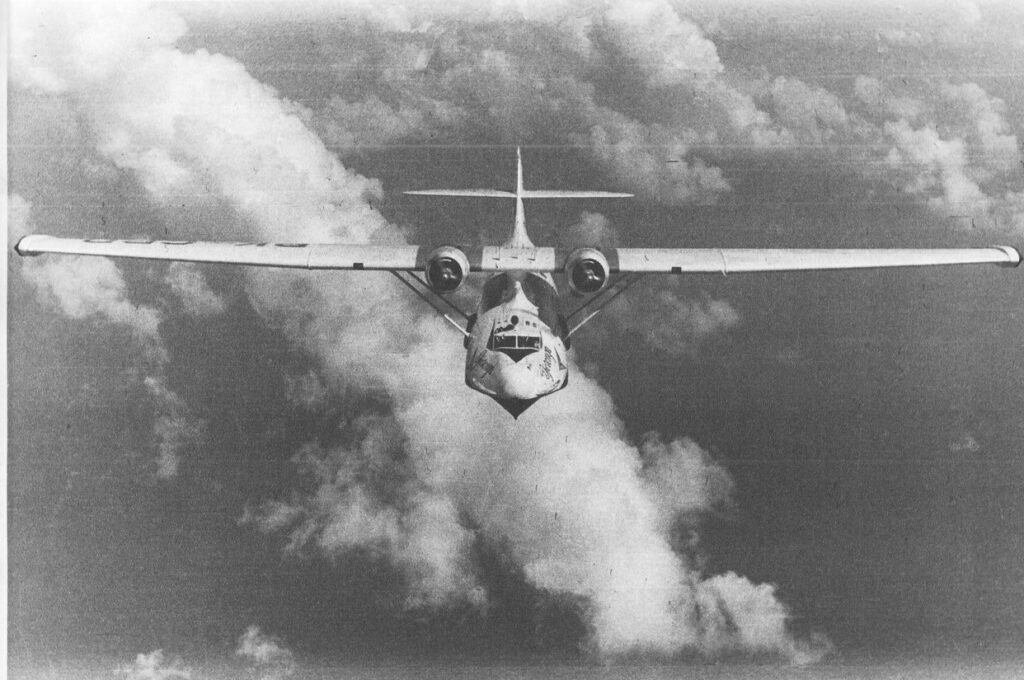

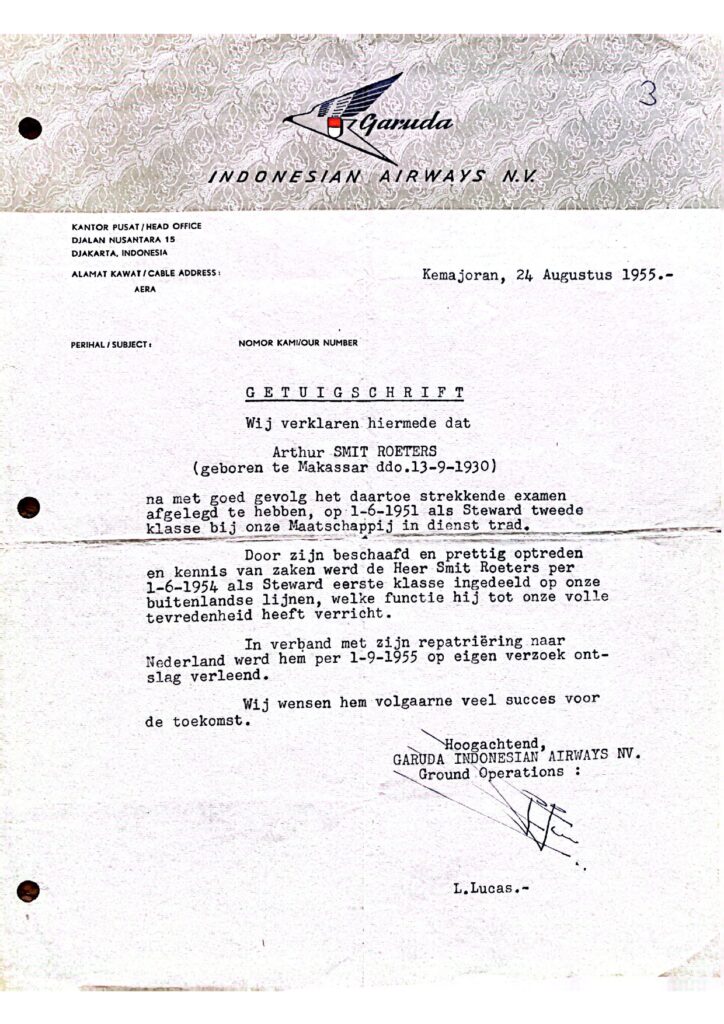

1950s,Catalina,Garuda,GIA,Indonesia,PBY-5A

By Arthur Smit-Roeters

What it was like to fly on board a Catalina in the early 1950s in Indonesia

Recently, a good friend presented me with a fantastic book: 80 Years, A Tribute to the PBY Catalina, authored by Hans Wiesman. Some of my flying time in the 1950s with the national airline of Indonesia, Garuda Indonesian Airways (GIA), was being in the air as a steward on a PBY-5A Catalina amphibian flying boat, a period of pioneering. I remember being accepted for training after passing some tests and I was ready to make my first trip after about three weeks of classes. One of my first flights was on board a Catalina flying boat, an ex-WWII long-range patrol seaplane converted into one carrying 16 passengers. Long-forgotten images pop up in my mind.

The front office or cockpit was not my realm. Before today’s glass cockpits became the norm, in my days they had “steam gauges.” I flew on board a “steam gauge” airplane. A somewhat condescending term used to indicate a plane is equipped with old-fashioned and almost obsolete instruments. The electronic Flight Management System now commonplace had not appeared in anybody’s dream. The pilots were it. Navigation was by dead-reckoning and a simple Radio Direction Finder (RDF) was an essential piece of equipment. Yes, it was all manual labor. For me, 88 years old in 2018, it’s unbelievable how things have changed.

What a Garuda amphibian PBY-5A looked like inside

My workspace, located between the cargo area in the tail and cockpit, consisted of two cramped compartments, each holding eight passengers. The wheel wells were located between them. One had to stoop through three hatches to get to the front passenger compartment from the cargo area where my rudimentary pantry was located. I could almost lean on the cargo in my back when I was facing the portside located pantry in front of me. I had to stoop through another hatch, the fourth one, to get to the pilots.

Each passenger had access to a life preserver. There were no emergency exits. An inflatable life raft was not part of the inventory. The lavatory was just a bucket covered by a seat and located in the tail section. Space was very limited and one could not stand straight up.

The only thing I didn’t like during my flying time was the smell of even an empty airsickness bag that was made of asphalt tar-impregnated paper. The smell induced the user to have a quicker barf time. Since the plane was not pressurized, we could not fly over the weather. Turbulence made this bag a popular item for an airsick passenger.

The inside of the plane was a bare-bones affair. Only the two cabins had a fuselage covering, the rest of the plane inside was just aluminum skin painted chromate green. There were no reading lights or airvents over the non-adjustable passenger seats. No night flights were scheduled, but there were delayed flights with arrival times past sundown. A sunken aisle divided each eight-passenger compartment along the keel into four seats on either side. Passengers faced each other. When two people sitting opposite each other wanted to stretch their legs they had to first figure out where to place their feet.

My guests had to board via a door with a high threshold where the port-side gun position was located in the war years. Thus, stairs with a lot of steps had to be rolled up to the side for entry or a bobbing launch when on water. After the first obstacle, the passenger had to crawl through the hatches in the bulkheads to get to the front cabin. There were no overhead bins and suitcases of all sizes had to stay in the cargo area, the space where once the two gun positions (blisters) were formerly located. Carry-ons as we know them today didn’t exist.

Getting aloft

Prior to getting aloft, I had to make sure everybody was strapped in. The sounds and sights of a Catalina flying boat takeoff from the water were always spectacular.

Before the start of an engine, one could hear the groaning and clanking valves as the propeller was rotated through nine or more blades with the ignition “off” to clear accumulated oil out of the bottom cylinders of the double-row, 14-cylinder engine. Then with ignition “on” the engine burped a few times before a smooth sound indicated all was going well.

After taking in the floating anchor and when the aircraft was lined up, takeoff power was applied and with the increasing speed, foam started to blow past the windows. The plane was about ready to leave the water when we could hear a sound like skimming over a gravel road under our keel, announcing the aircraft was hitting the top of the waves. With the two engines close overhead and no sound isolation, it was very noisy inside, but the auditory sensation of healthy engines was always music in my ears.

Aloft

As seen from the aircraft’s window the jungle below looked like an endless and dense cauliflower field with an occasional bare patch where natives had slash burned the area and planted their corn or cassava. The soil looked yellowish. It certainly was not loam. Over the years hardwood trees were able to survive and thrive with the help of the monsoon rains with precipitation of 120-145 inches a year in the lowlands. A downed airplane would disappear in the dense jungle foliage. It seemed all the water in rivers had a brownish color and crocodiles were ever-present.

With an average cruising speed of 108 knots, and being in the air for many hours, it was difficult to get out of one’s seat for some leg stretching, but some people did. The distance between Jakarta and Singapore is about 550+ miles. With a cruise speed of 108 knots per hour, the flight, with a stop in Billiton (Belitung), and a Singkep sea landing, made the flight an all-day affair. Logging 100 hours of flight time per month in PBY-5As, C-47s/DC-3s, and Convair 240/340s was almost normal for me.

Tasks on board

Once in the air, I doled out cold lemonade drinks, first to the cockpit crew since they were at their stations to do their checks long before the pax boarded. Then I went around with reading material including various magazines and newspapers. Safety cards? Are you kidding? On the Singapore flights, I had to help passengers with deciphering and filling out their customs and health forms printed in English. Inflight meals were very simple. No alcohol was served.

Flight impressions

I still remember landing on the river where the Dutch Bruynzeel lumber company had their sawmills at Sampit, a jungle outpost. The slow-moving river water had a brownish color due to suspended sawdust, tree saps, and rotting leaves. The employees were always happy to see the Catalina since we brought with us one or two tall wooden reinforced boxes filled with movie reels for their entertainment during the coming week.

Although a ground crew in their boat made sure that the landing surface was clear of obstacles, we always made a pass over the site, looking for submerged logs. We had no problems getting back in the air, but I remember there was a bend in the river at the end of the takeoff run. The tree-lined jungle river was wide enough for maneuvering when checking the magnetos of each 1200-horsepower P&W R-1830 before departing. It was great to look up at the tall trees on both sides of the “water runway” at the start and then feel how slowly but surely the big 104-foot span barn-door wing (it was not equipped with flaps) lifted us over the trees at a leisurely speed of 75 to 80 knots indicated air speed (KIAS) and then continued at a leisurely cruise speed of about 108 knots or about 124 mph.

All landings on smooth water were power landings. One time the captain allowed me up front to witness a stall landing, normally used when the waves were choppy. The airplane’s nose was up high and the rudder pedals were useless. The Dutch ex-Navy WWII cockpit crewmembers were excellent pilots and sailors.

I made many flights to Kallang Airport (Singapore), via Billiton (Belitung) Island and Singkep Bay where passengers were transported to and from the plane by a motor launch. On days when the sea had light swells, it was awkward to transfer some passengers between the up-and-down movements of the Catalina and the launch. It took some time for the landlubbers to deplane or board.

While waiting for the Singapore-bound passengers it became unbearably hot inside the plane. The crew, in various stages of undress, moved to the top of the wing. At one time the board engineer had to relieve himself and went to the end of the portside wing that had its wing float in the water. A devilish crewmember suggested that the rest of us run towards starboard at the “right” time and see if we could flip the engineer off the wing tip. Running towards the high starboard end, the portside float lost its suction, and the engineer, wearing only his briefs, lost his balance and tumbled into the sea. The few seagulls looking for handouts could not stand his loud and unhappy cursing and left.

Another time on short final to the steel-matted Billiton strip in bad weather, one of the engines acted up and the propeller had to be feathered. After circling the area at what seemed just above treetop level, the pilots spotted the strip, and then the remaining engine called it quits! The PBY became a big glider, which took up valuable runway space and thus overran the airstrip. No power meant losing hydraulic pressure in the lines and no brakes. We didn’t have to disembark in the mud since a truck picked us up. There was a light drizzle and our miserable bunch was taken to the terminal, a simple bamboo structure with a palm frond roof.

In the early 1950s, all countries along the western Pacific Ocean rim were still in the process of recovering from the devastation caused by the Japanese war machine. I remember many items were exorbitantly expensive if you could find them. This included nylon stockings, parachute nylon, yardage of nylon, yardage of silk, cigarettes like Lucky Strike and Chesterfield, Johnnie Walker Red or Black Label Scotch whiskey, oranges and apples imported from Europe, etc.

A few crewmembers thought they could make a quick buck, but since nobody was a professional smuggler, things didn’t turn out well. The customs people were smarter than the would-be smugglers.

I remember on a return trip from Singapore somebody was going to make a lot of money by illicitly importing a shipment of 144 cartons of Chesterfield cigarettes. The customs officials in Billiton got word about the attempt and the crew was warned about it while in flight. The response was quick and the big package was pushed out of the plane through the ventral gun hatch below in the tail. Some fishermen may have found lots of cigarettes, manna from Heaven, in their fishing nets,

Billiton customs always came on board to check for suspected contraband from Singapore. On a flight before me, they hit the jackpot. The Catalina had a wooden floor and when the law man picked up a loose string, he unknowingly untied a knot. A bundle of nylon burst out from under the floor. There was no owner who claimed this expensive shipment.