Written by David Keller

The Airline Deregulation Act was signed into law by President Jimmy Carter on October 24, 1978. This piece of legislation had a wide-ranging impact, and the airline industry in the US would never be the same.

Some of the major changes were:

- Airlines would find it much easier to add and drop routes. This would allow carriers to enter highly coveted markets, while at the same time, subjecting them to new competition on their own lucrative services.

- Intrastate carriers would no longer be bound by state lines, as they could be certified to operate routes outside of their home states.

- Supplemental airlines could offer regularly scheduled services as opposed to only charters.

- Small carriers (primarily those seen as commuter airlines) would have the opportunity to operate larger aircraft, and potentially compete with the established carriers.

- New airlines could be formed to provide additional competition, and potentially lower the cost of air travel, thus bolstering the industry in general.

- Mergers would be approved at a much higher rate than in the past, which opened the door to carriers expanding through acquisition.

The most immediate impact of the legislation was that the established airlines were able to take advantage of their new freedom to add routes, largely by applying for “dormant” routes, as well as one other route they could add each year without needing to receive CAB approval. Since these companies had fleets, employees and the required certifications, they would be the first to take advantage of the new opportunities.

But the approach taken by the airlines varied widely, from extremely conservative additions to wildly over-ambitious route expansions. And many carriers had similar ideas for expansion, with Florida, Texas and Arizona being the most popular destinations for new service.

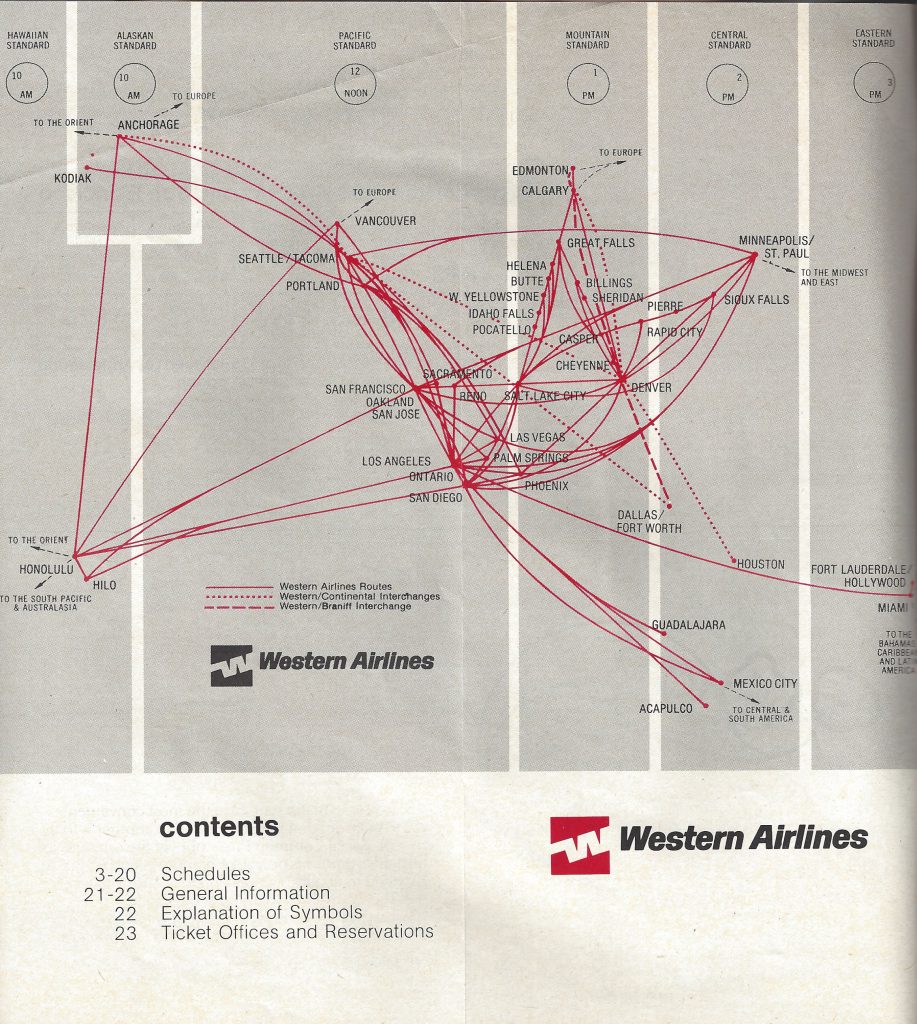

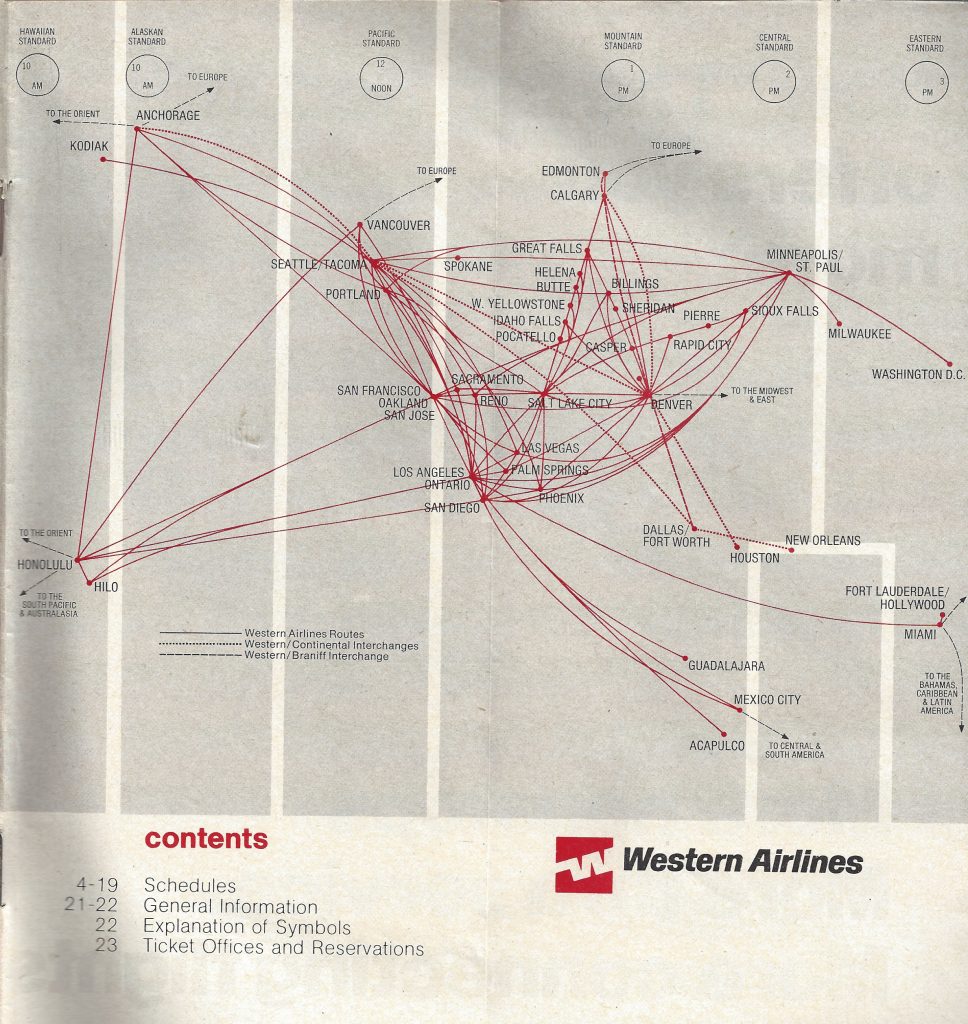

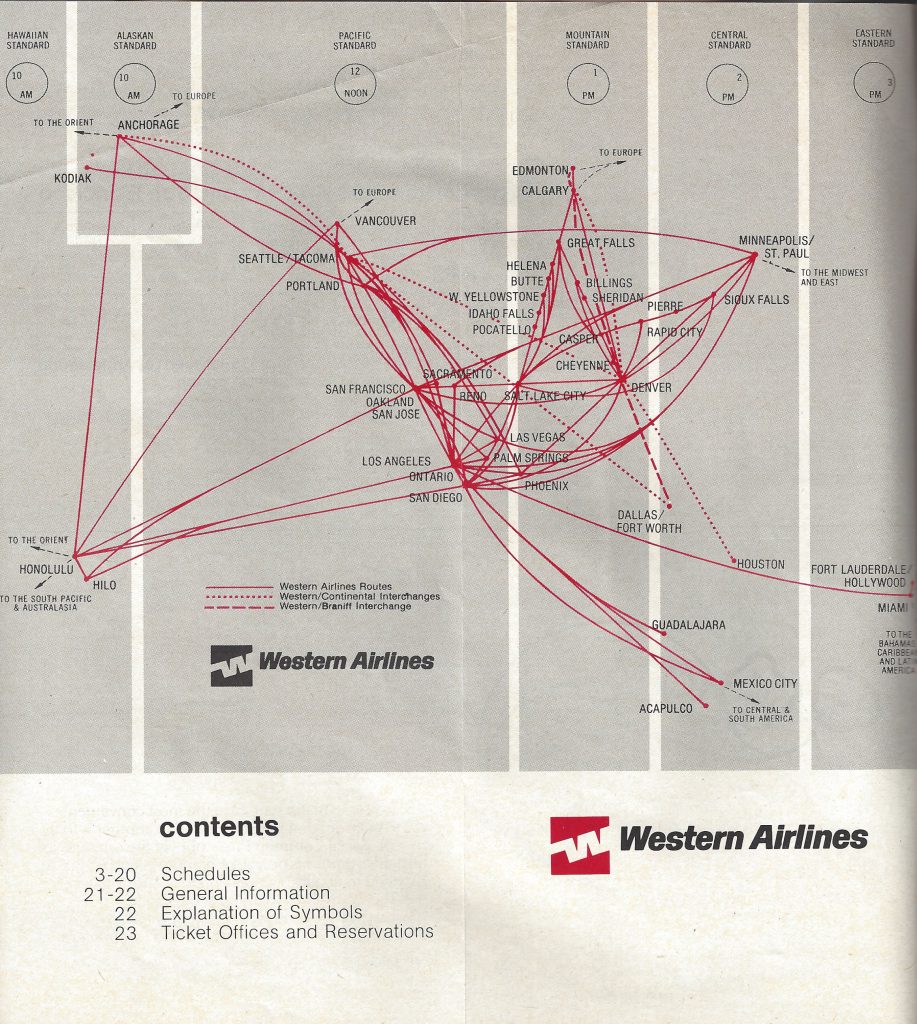

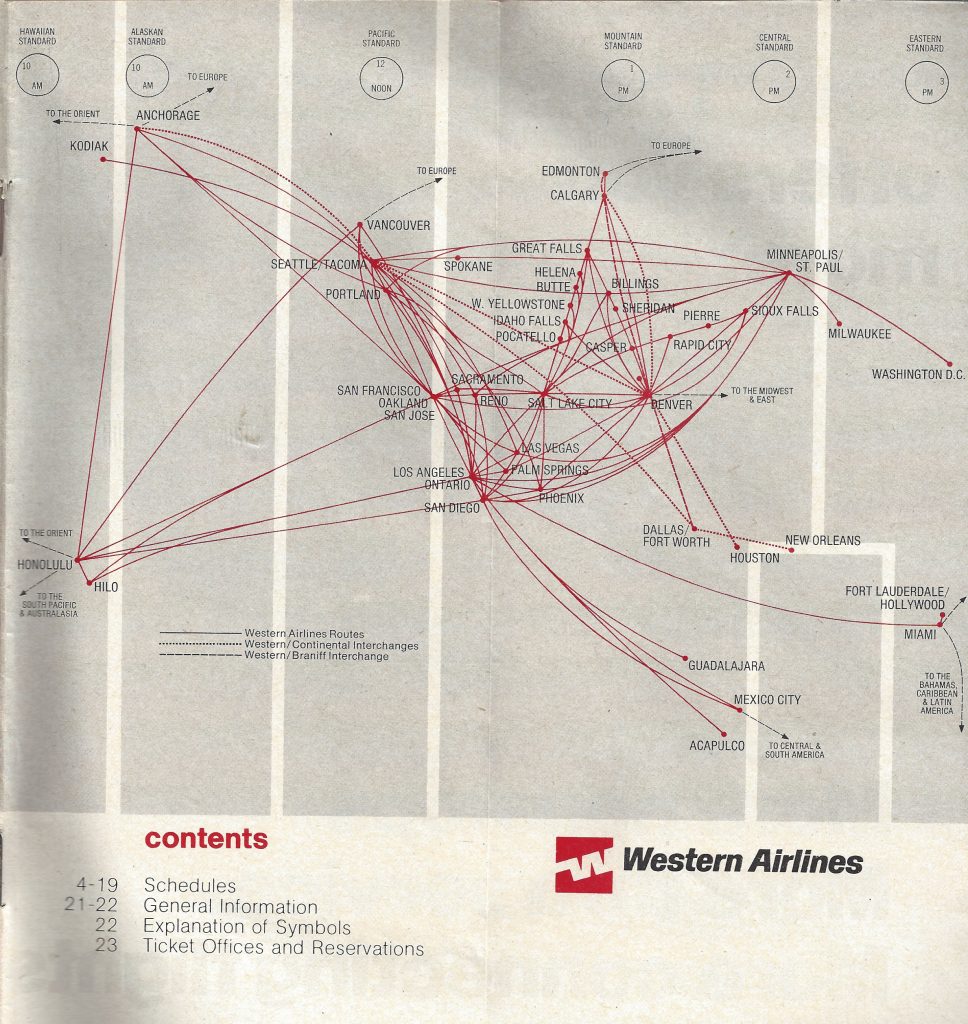

Western Airlines was probably the most conservative trunk carrier in the country. They were the last of the trunks to introduce pure jet service in 1960, and also the last to offer widebody service, finally introducing the DC-10 in 1973. It was one of the few not to order the Boeing 747.

So it should come as no surprise that the airline did not jump headlong into the uncharted waters of the deregulated environment. While most carriers promoted the start of some new services by early 1979, Western took a more measured approach. By the end of 1979, Milwaukee, Spokane and Washington D.C. had all been added from the airline’s traditional eastern terminus in Minneapolis/St. Paul. This meant Western had become a transcontinental carrier, offering direct (2 stop) service between the East Coast and Seattle.

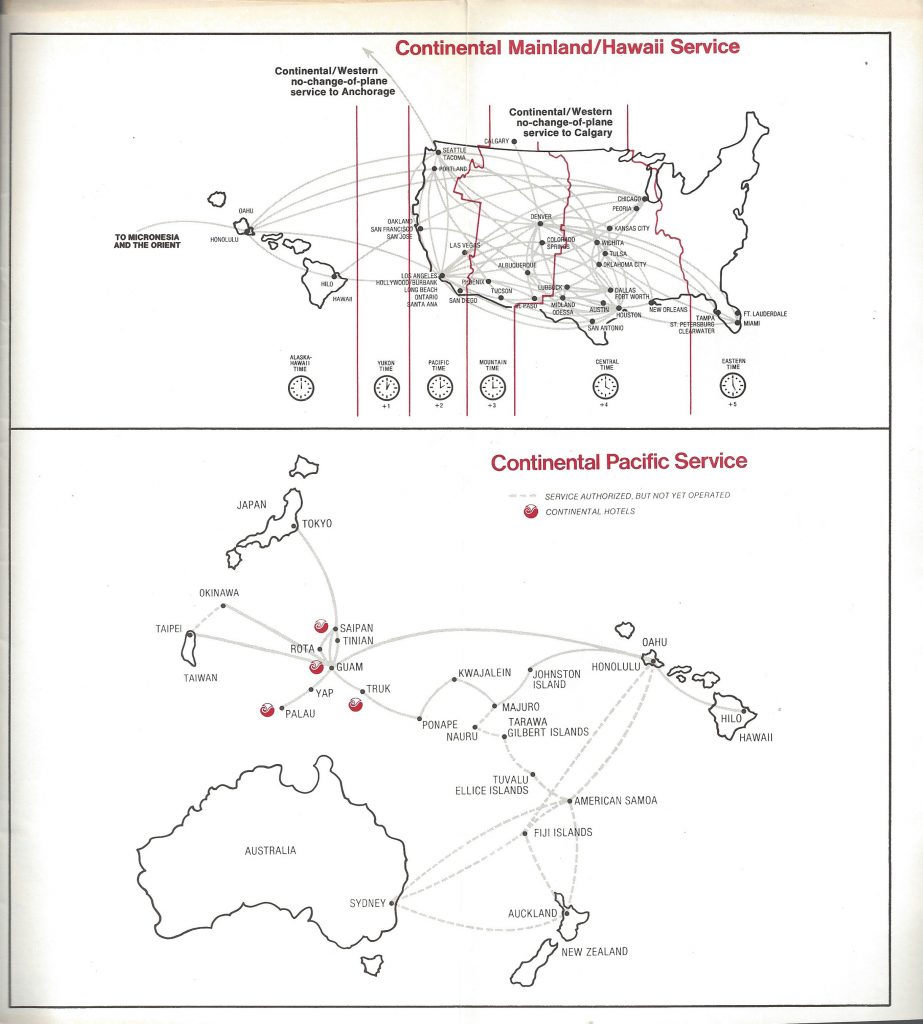

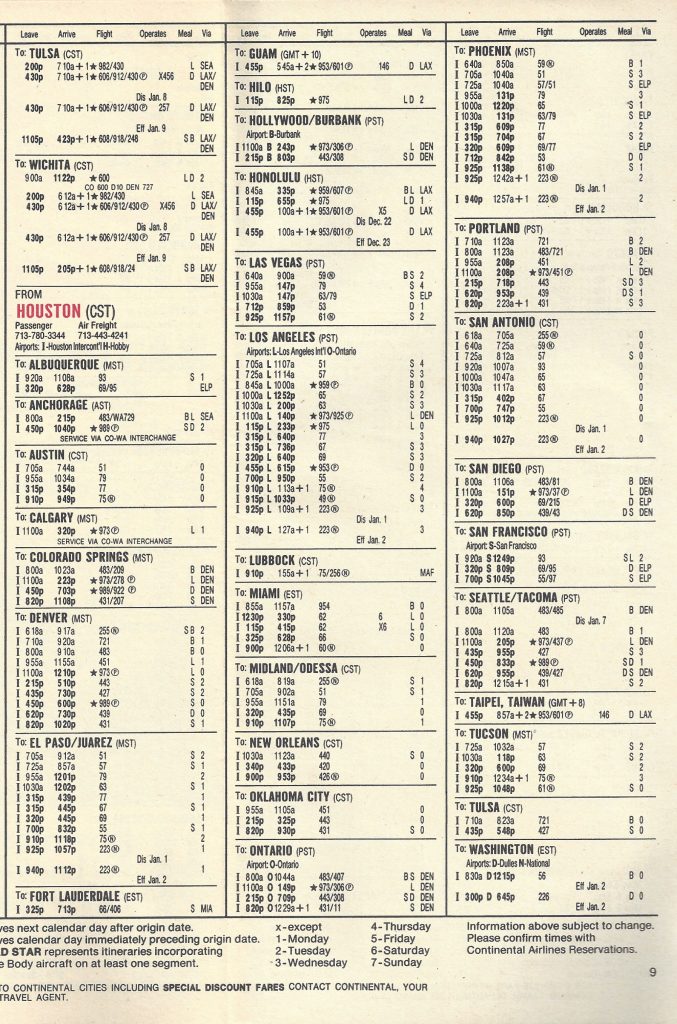

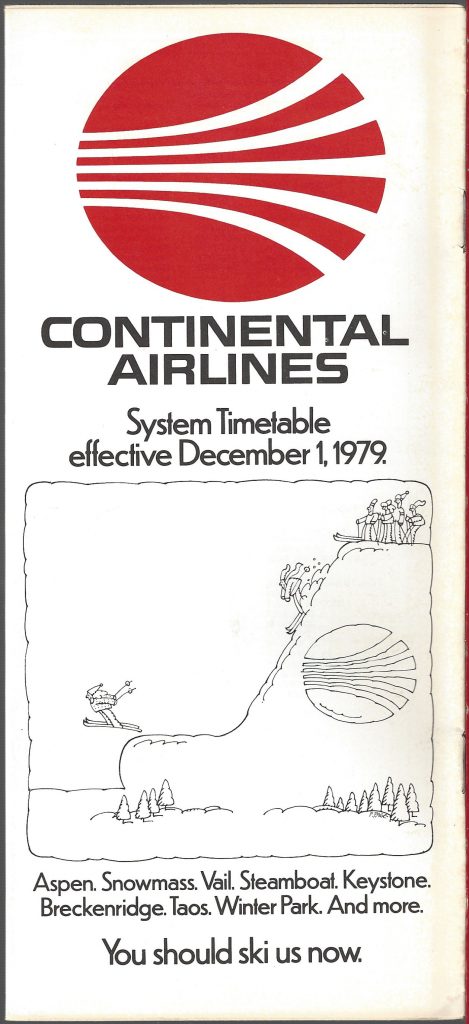

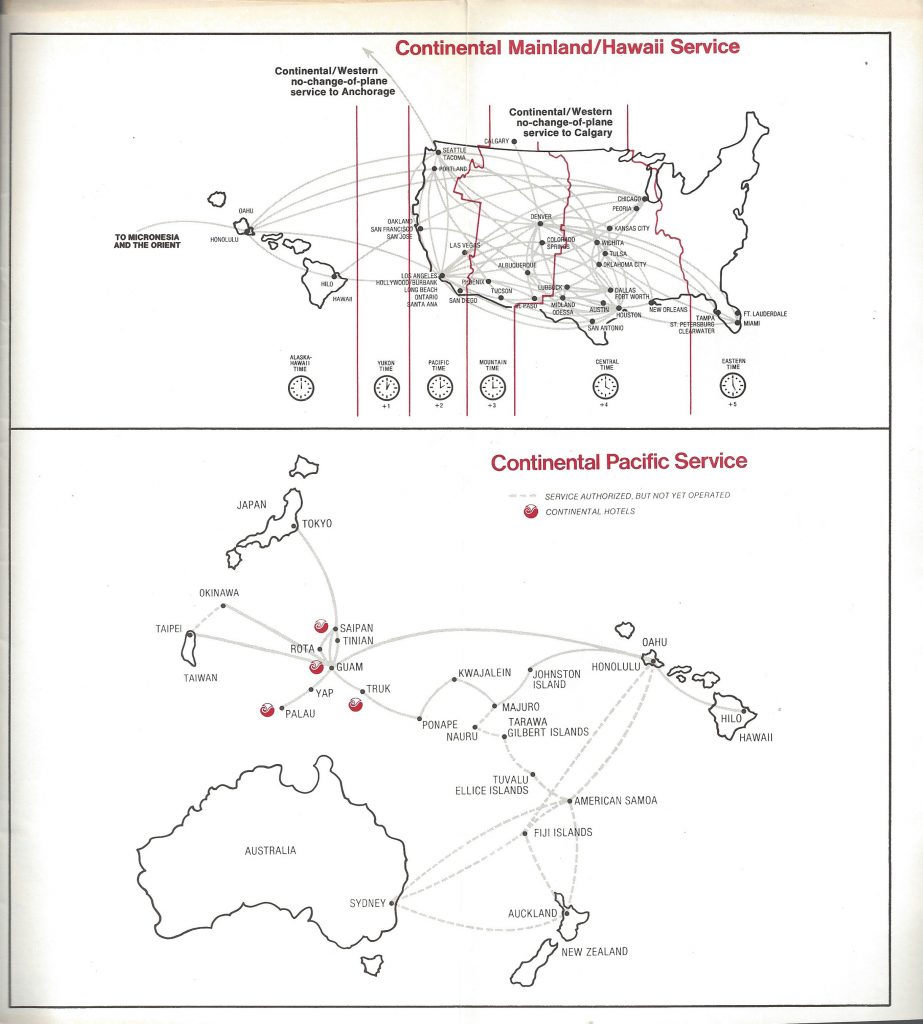

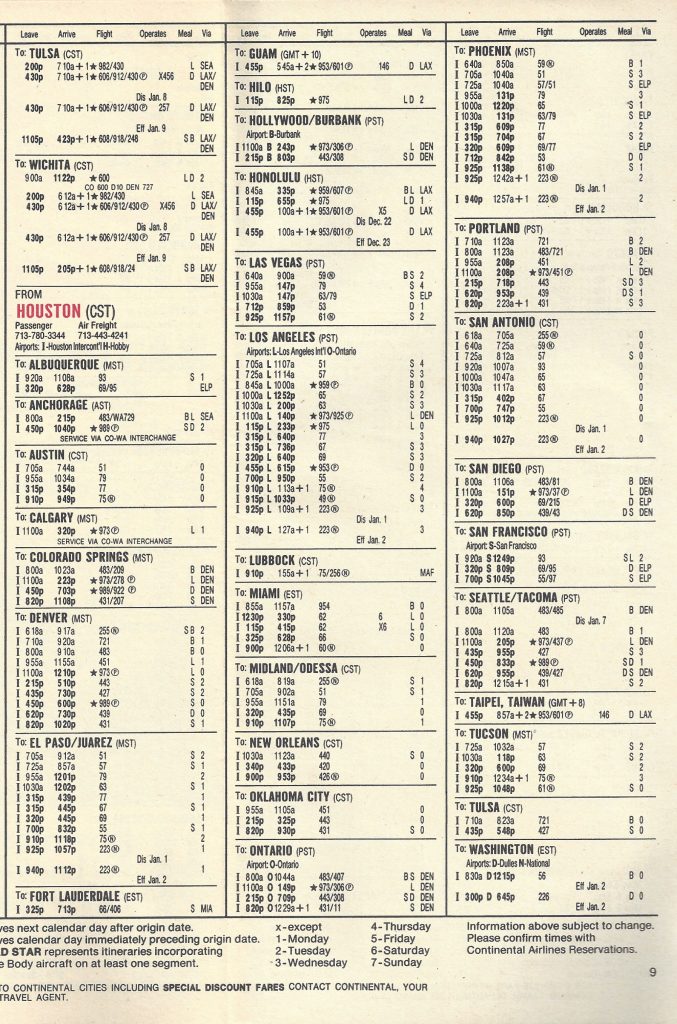

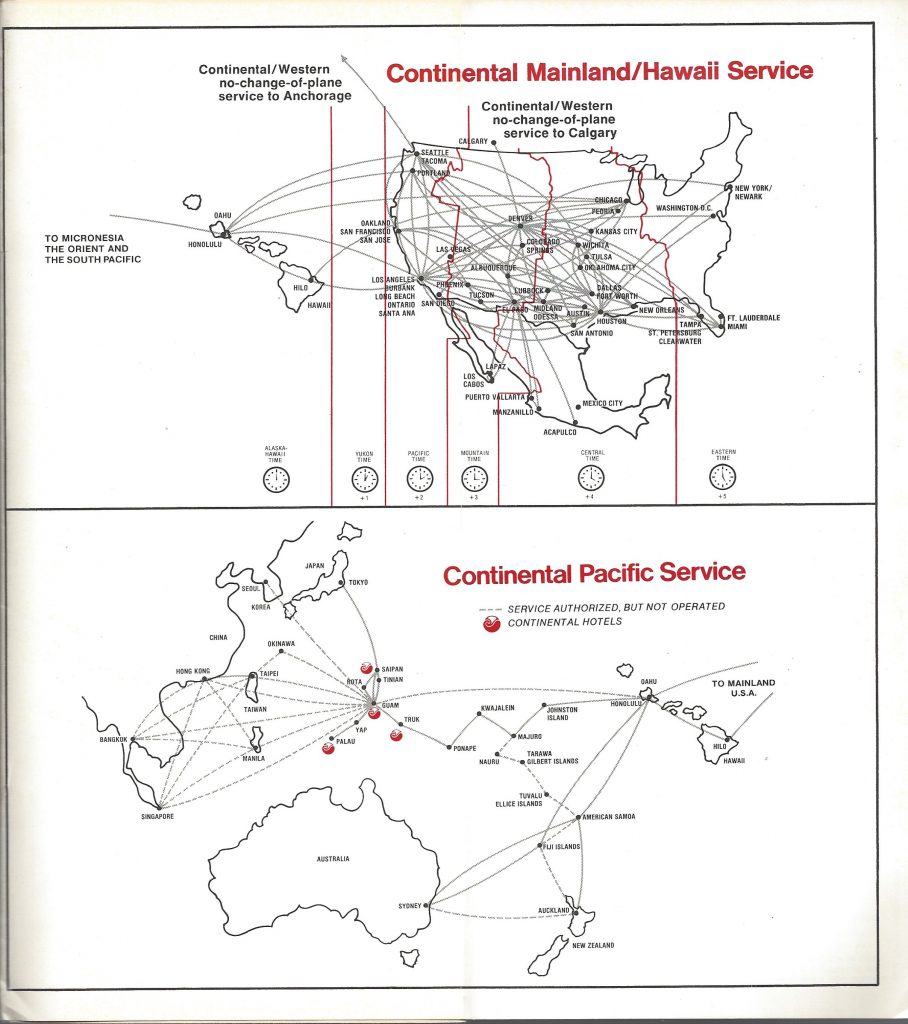

Another carrier to move with caution was Continental Airlines. By the December 15, timetable, Continental was promoting service from Washington/Dulles to Houston (starting January 2, 1979). Continental also joined the transcontinental ranks, with direct service from Dulles to Los Angeles (albeit with 4 stops).

By the end of 1979, Continental had added routes to New York City, as well as to Western Mexico. Additionally, long-delayed service from Hawaii to the South Pacific had also been inaugurated.

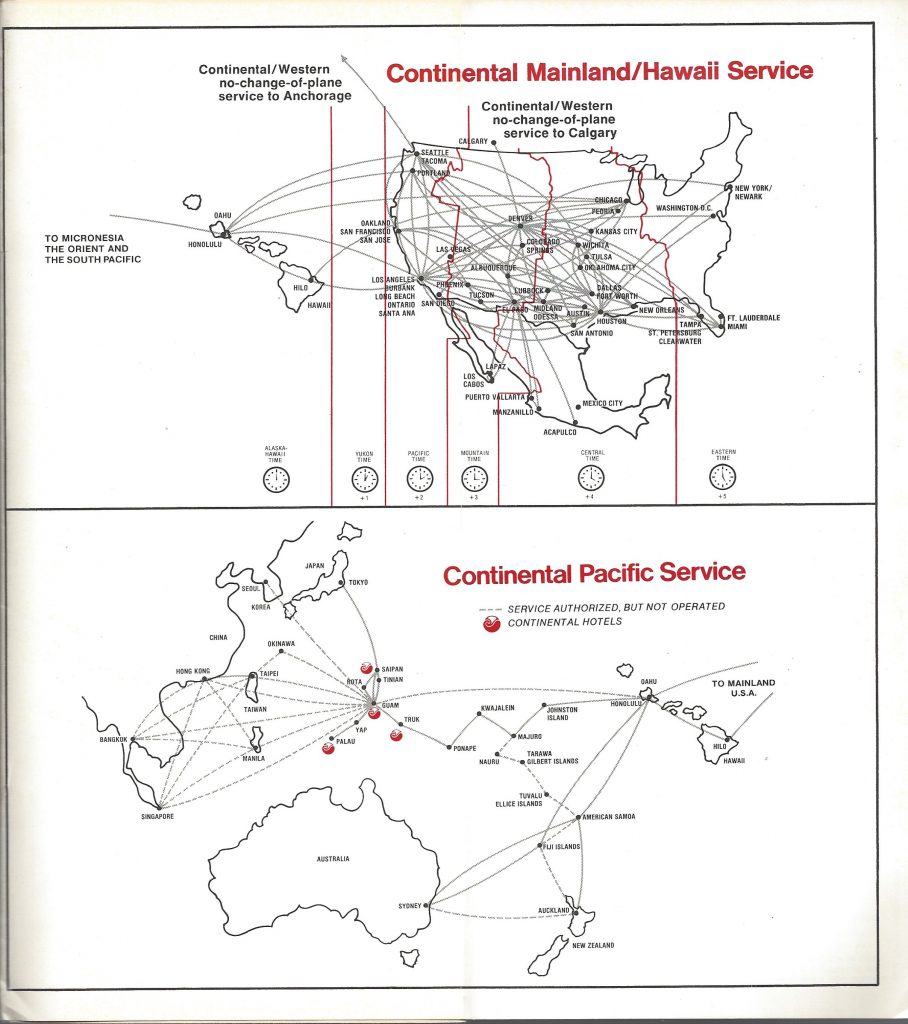

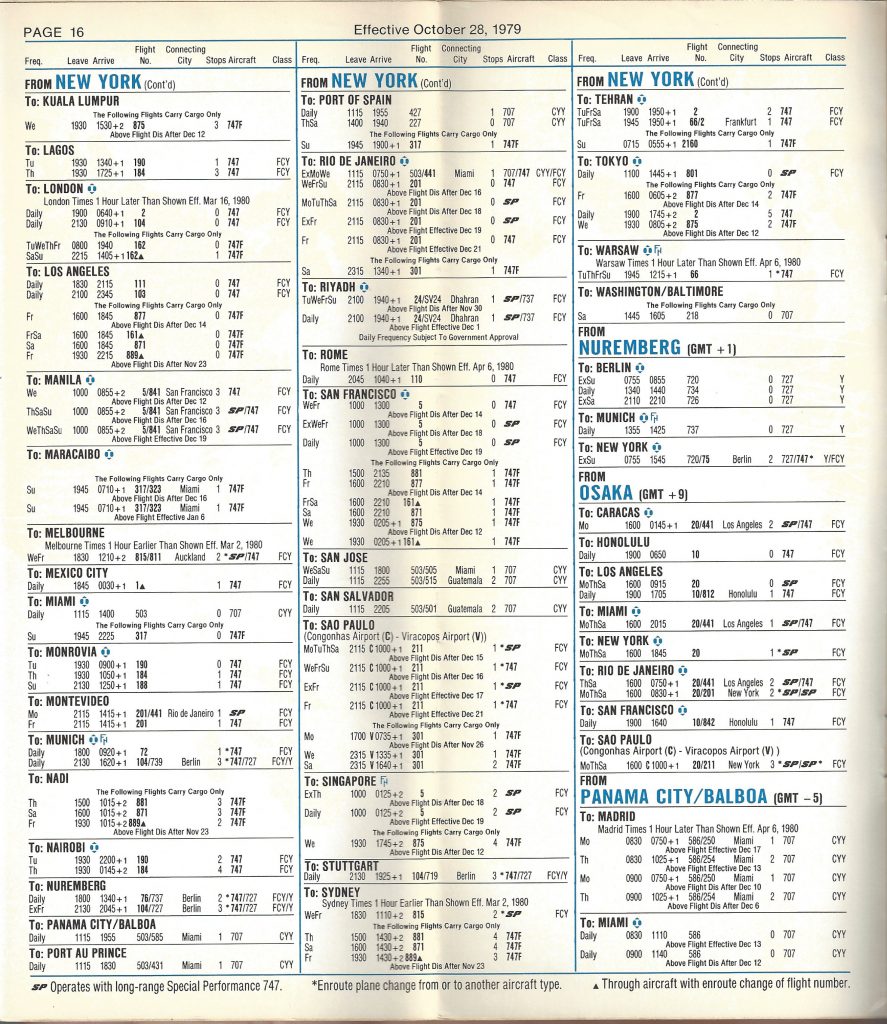

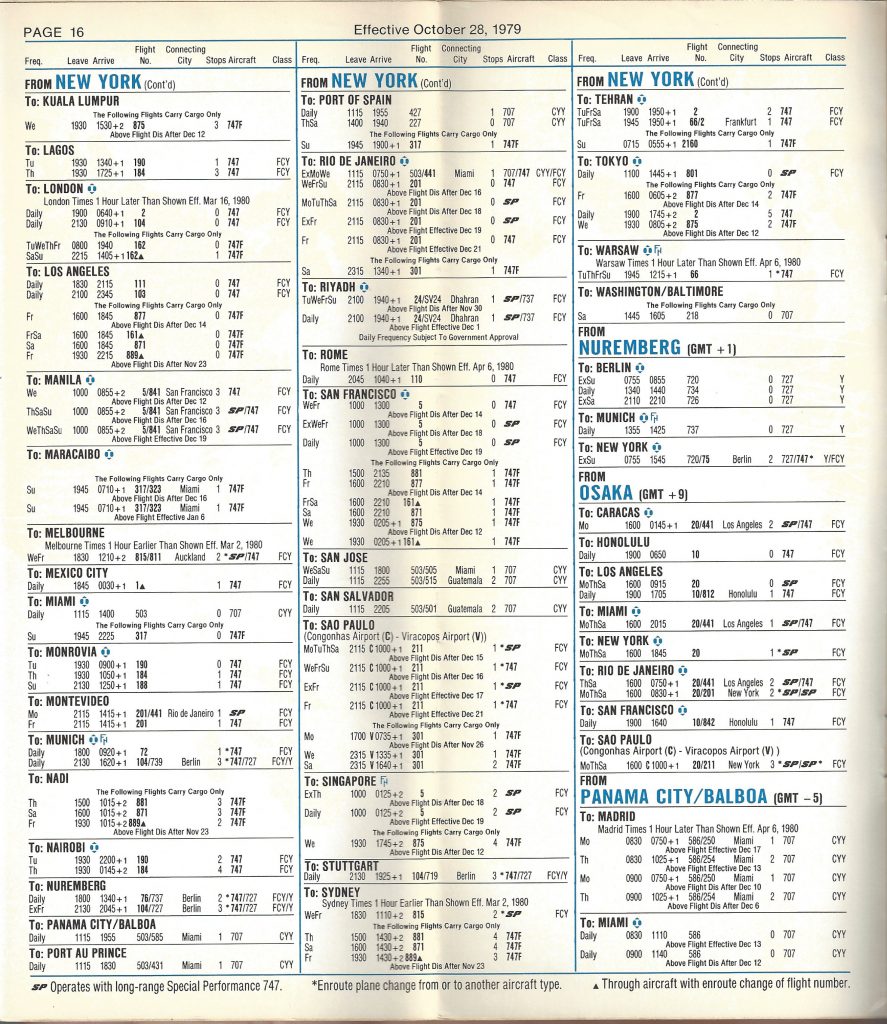

Pan Am’s many attempts over the years to acquire a domestic airline to feed its globe-spanning international network had largely been thwarted by other carriers claiming that such a combination would provide an unsurmountable advantage over other airlines, many of which had little or no international routes. Deregulation provided the opportunity for Pan Am to build its own domestic network, but given the fact that the carrier’s fleet was primarily built for long-haul intercontinental services (with the exception of the 727 fleet working the Internal German Services), acquisition was seen as the most viable path to that end, rather than individual route acquisitions. In the meantime, the carrier’s timetable dated October 28, 1979, does show a few domestic segments added, namely connecting New York with Miami and San Francisco.

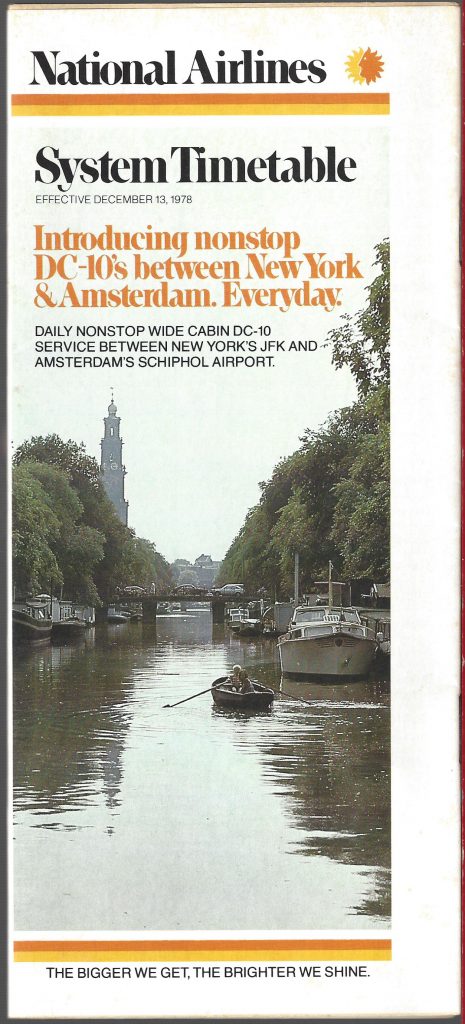

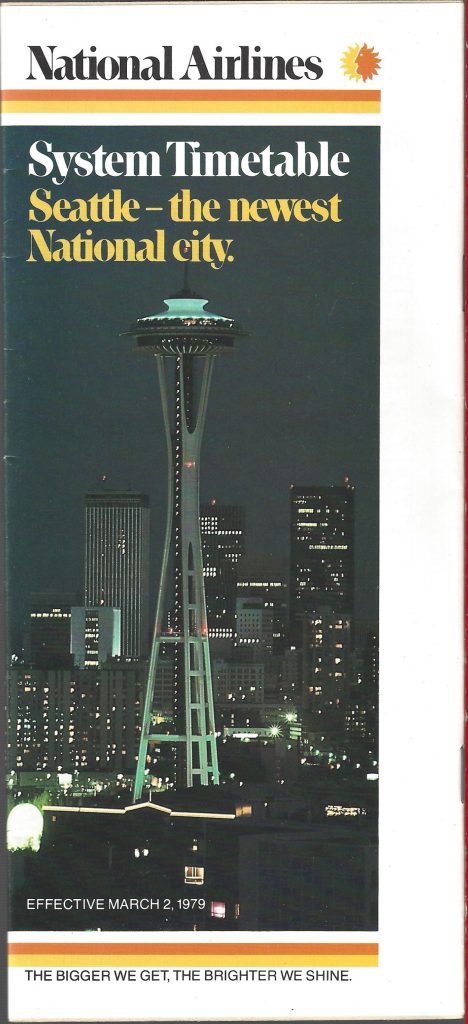

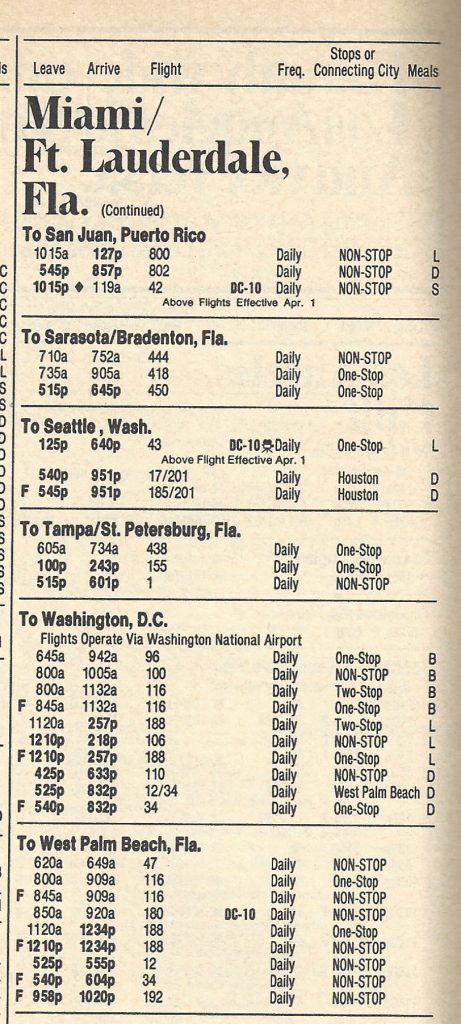

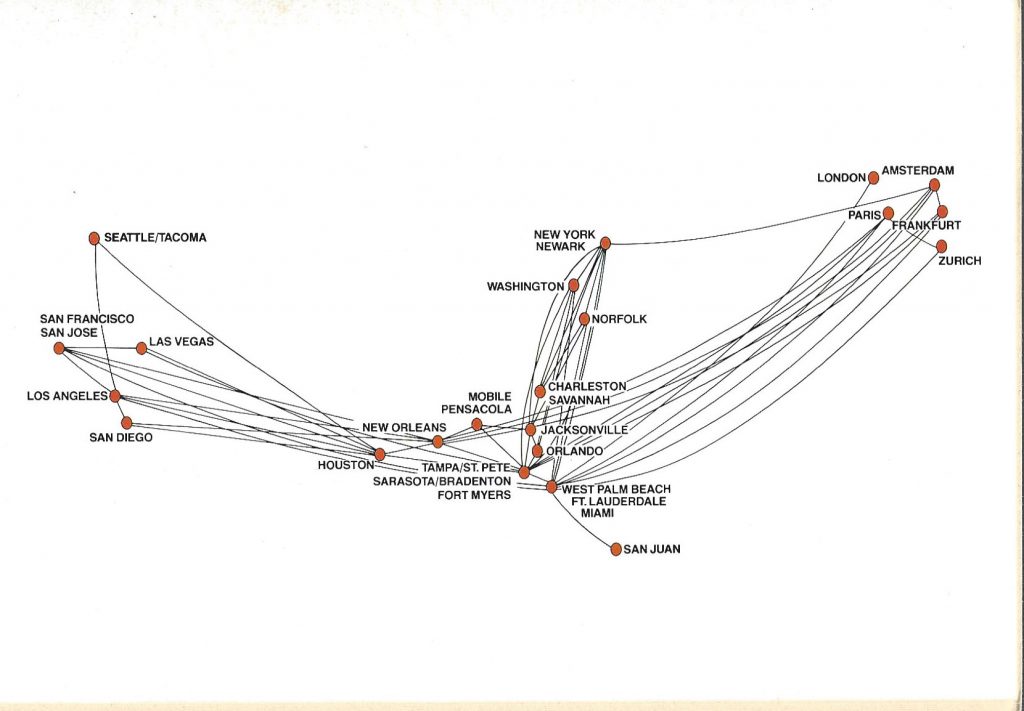

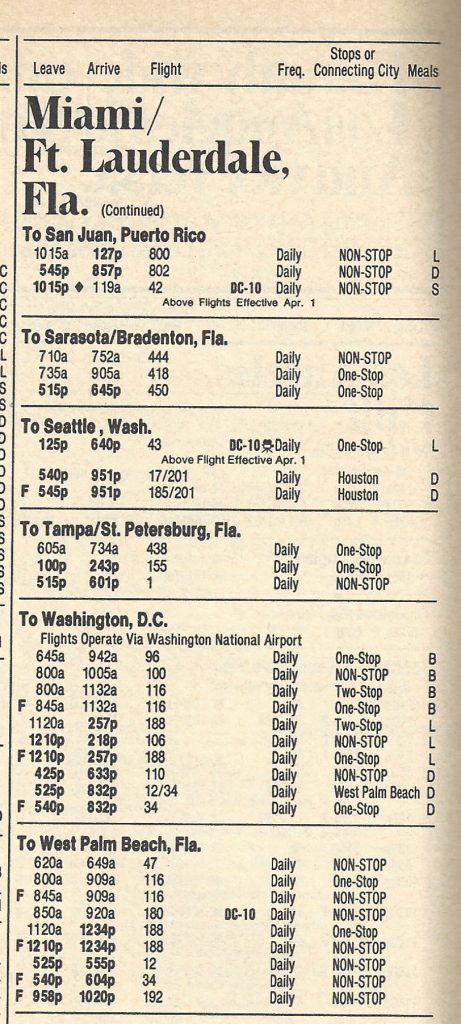

National Airlines was focused on expanding its footprint in the trans-Atlantic market, and only made a few tentative moves in the domestic arena. The March 3, 1979 timetable shows that Seattle was added with a route to Houston, with service to Los Angeles forthcoming on April 1. Also on that date, National started operating between Miami and San Juan with 3 daily round trips.

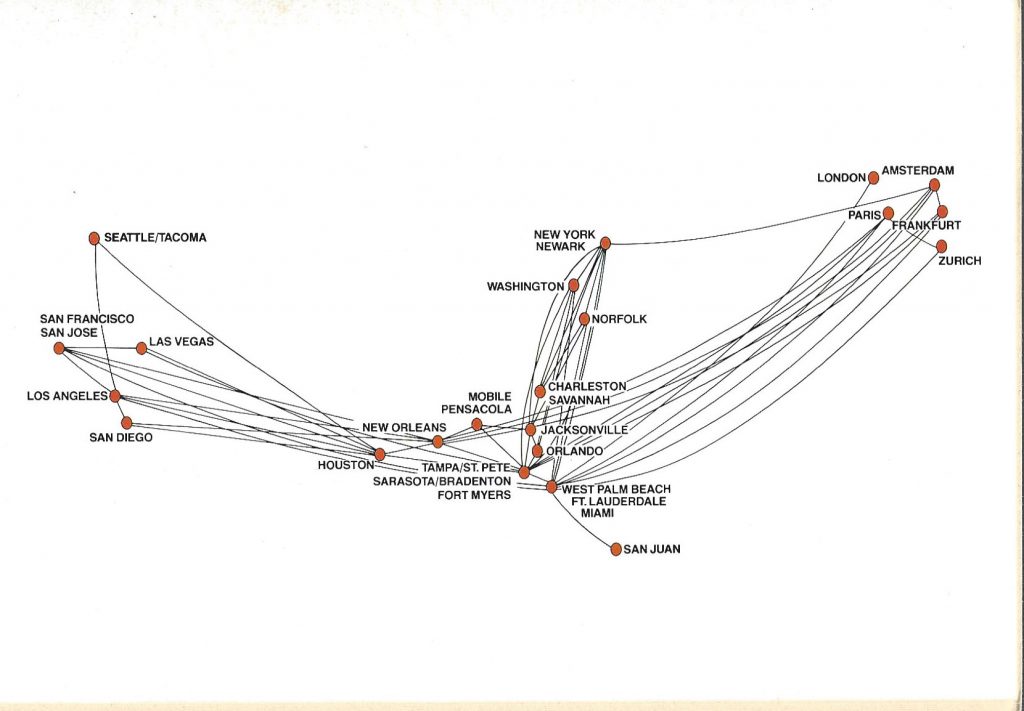

The fact that National attracted interest as a takeover target may have also resulted in a more conservative strategy, given the bidding war that ensued. The airline’s services remained essentially unchanged for the remainder of the year, as illustrated by the (condensed) route map on their September 5, 1979 timetable.

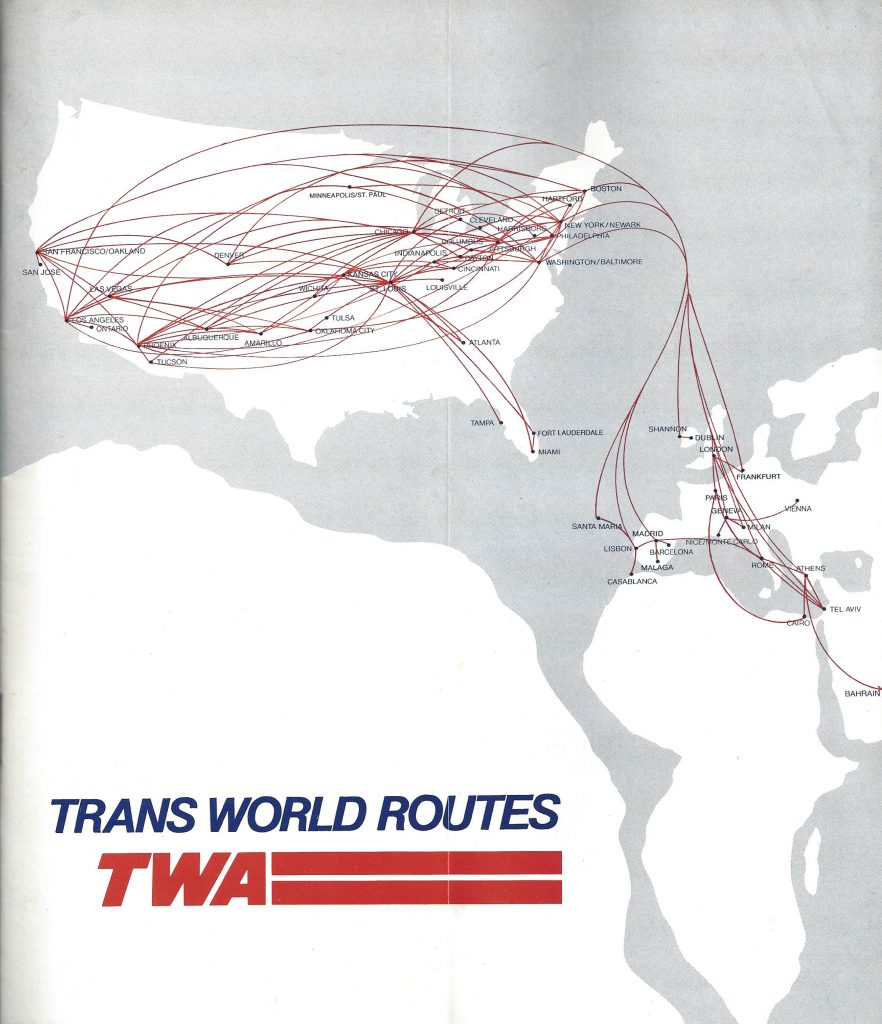

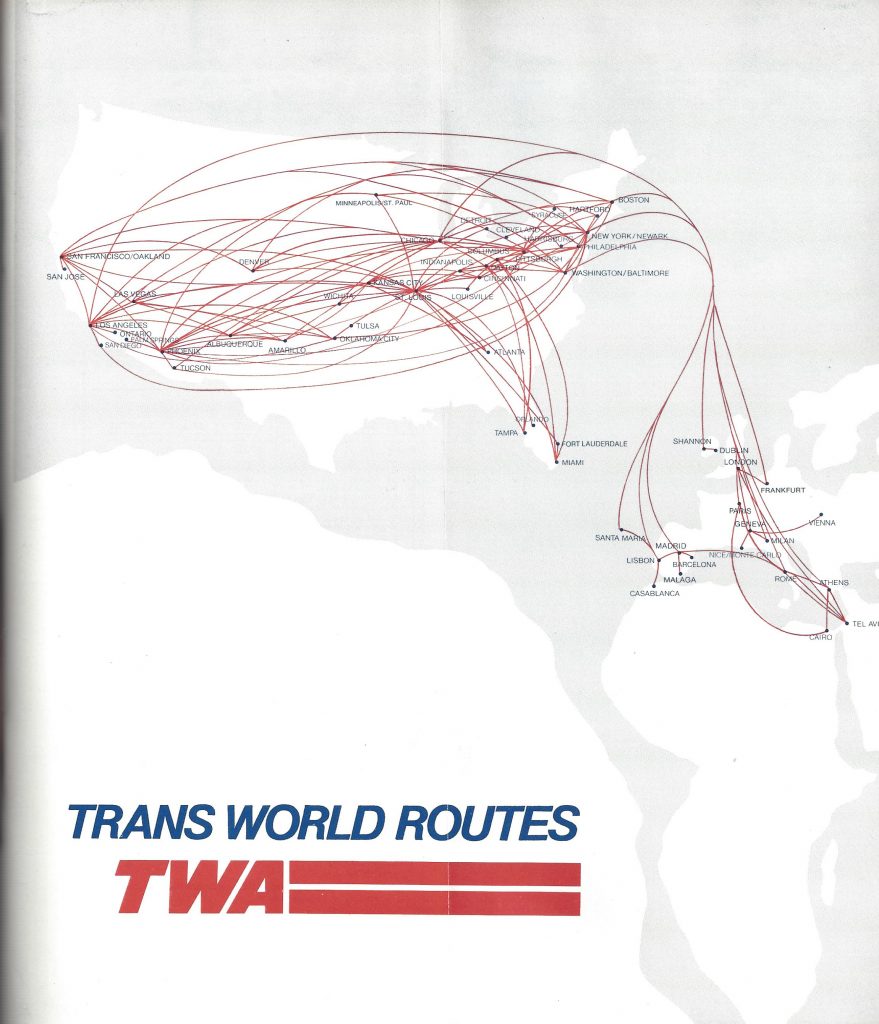

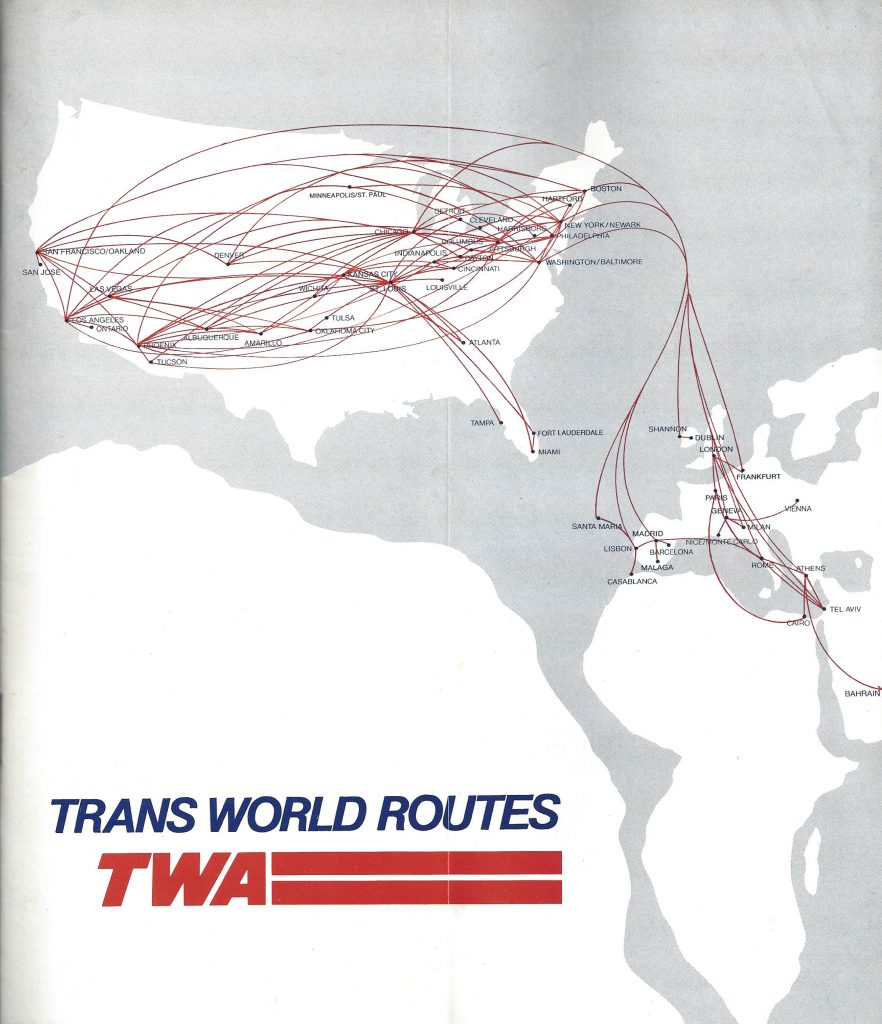

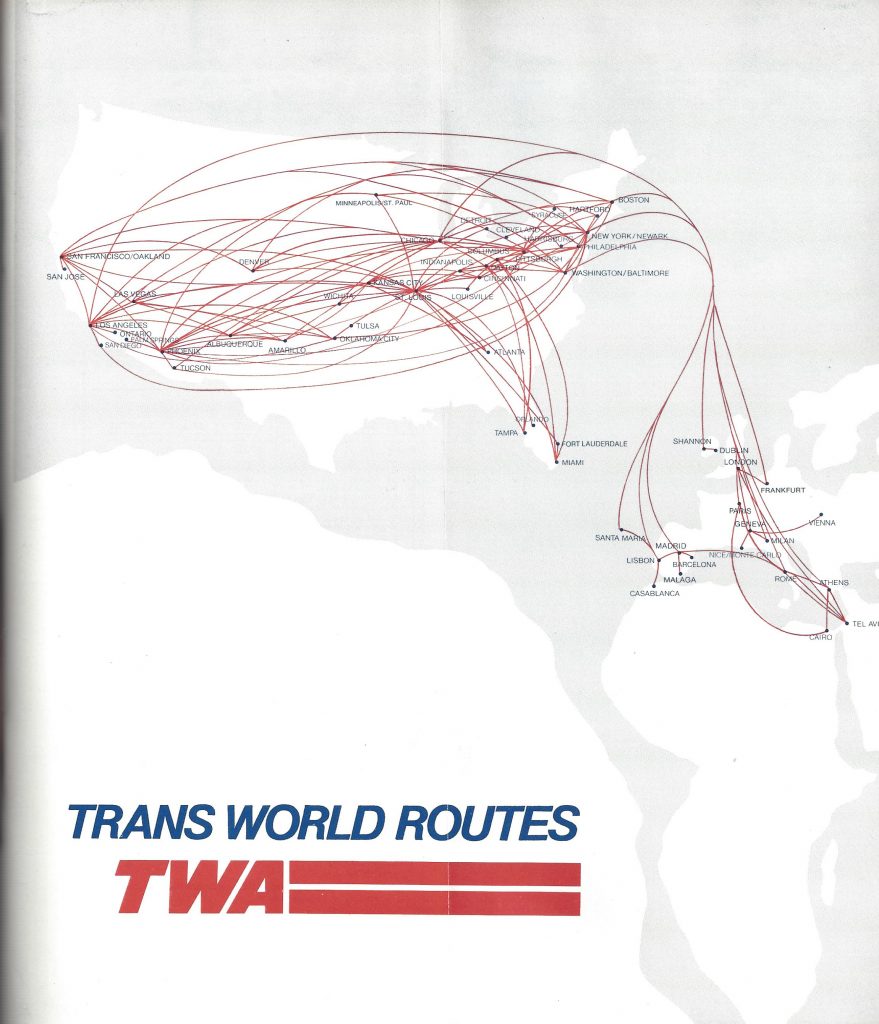

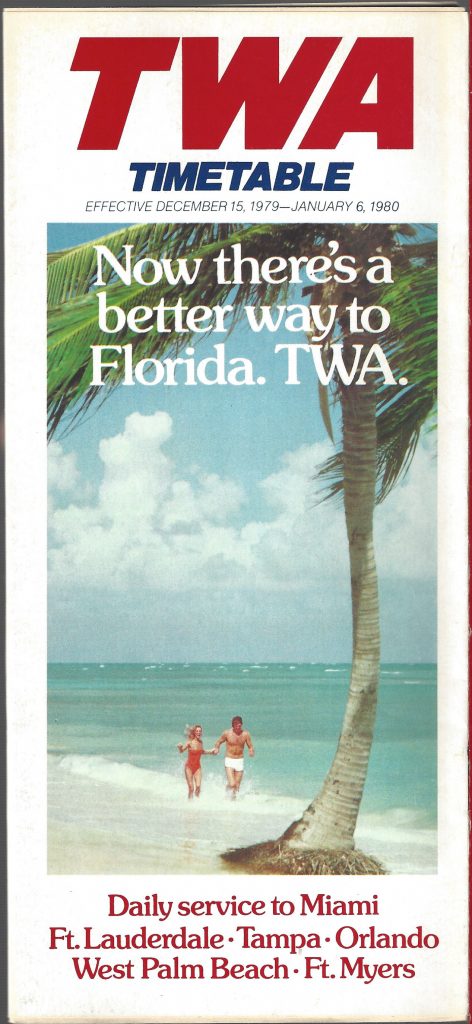

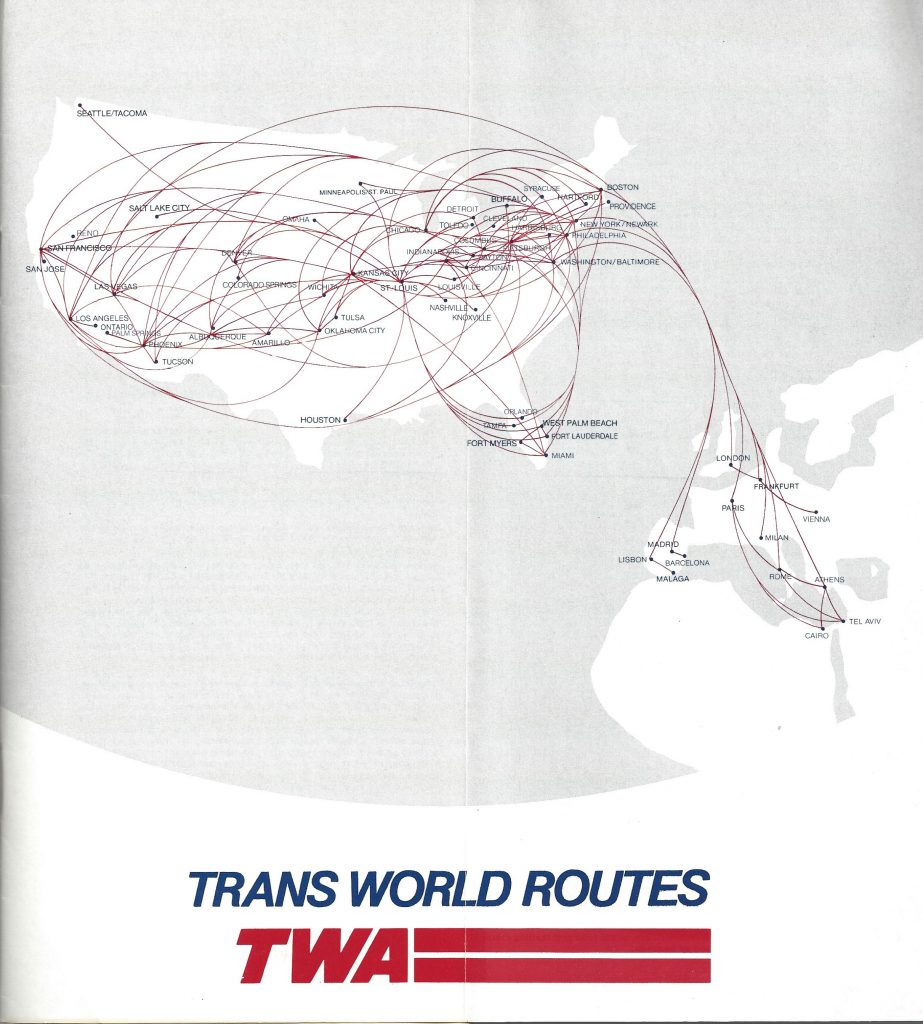

TWA’s initial route additions were also relatively meek, as the January 9, 1979 timetable shows new service between St. Louis and Minneapolis/St. Paul, and from Palm Springs to Phoenix, continuing to Chicago. (At this point, Chicago was still considered TWA’s primary domestic hub. It would be a few years before TWA would decide that they couldn’t compete with the likes of American and United at O’Hare.)

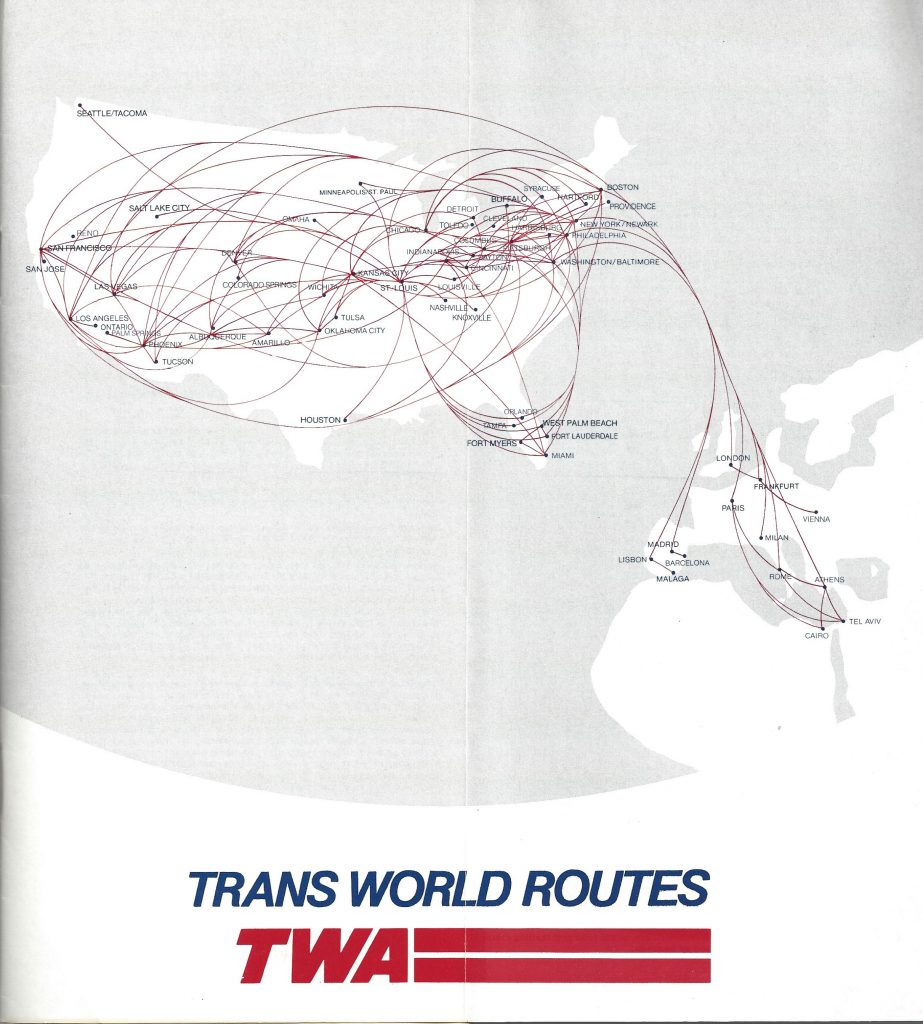

However, by the end of 1979, TWA had added routes from a number of new cities to St. Louis, and had also greatly expanded its footprint in Florida. As the December 15, 1979 issue illustrates, 3 new Florida destinations were added, and service to Florida was inaugurated from 7 cities in the northeastern US; Boston, Cincinnati, Columbus, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, New York and Washington. While TWA operated 37 weekly flights to Florida in the winter of 1978/79, by the following winter, that number had risen to 276!

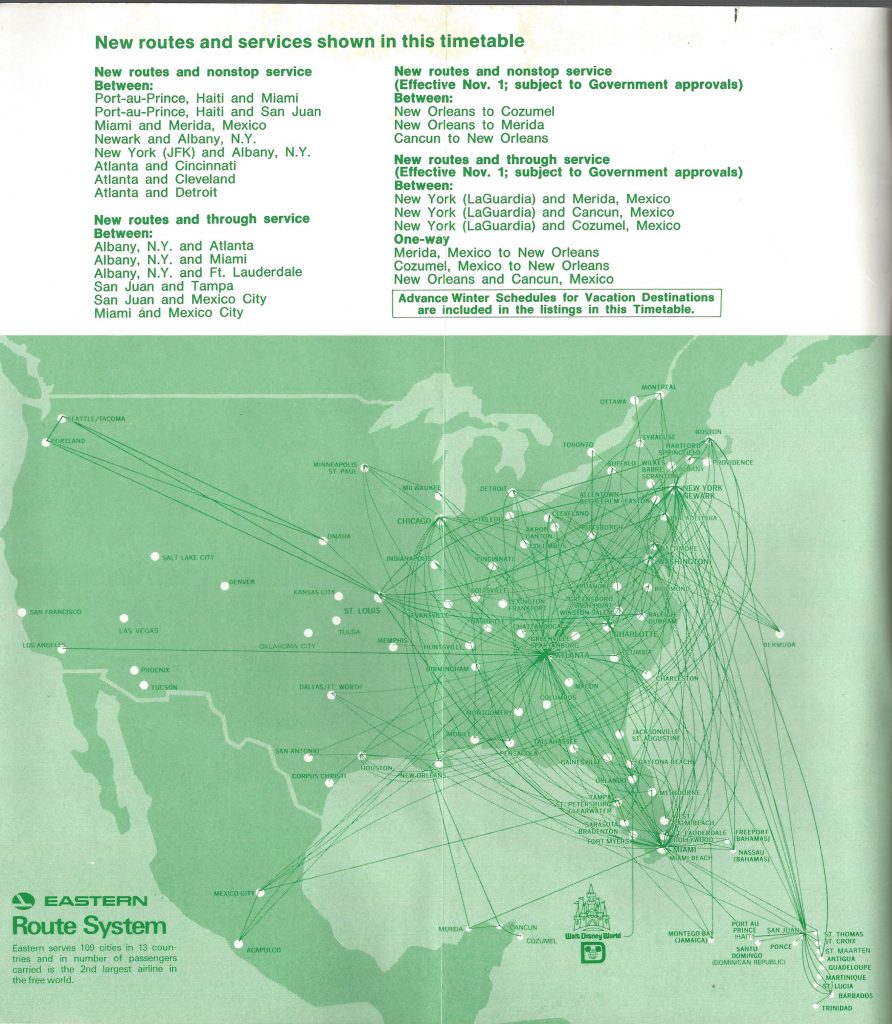

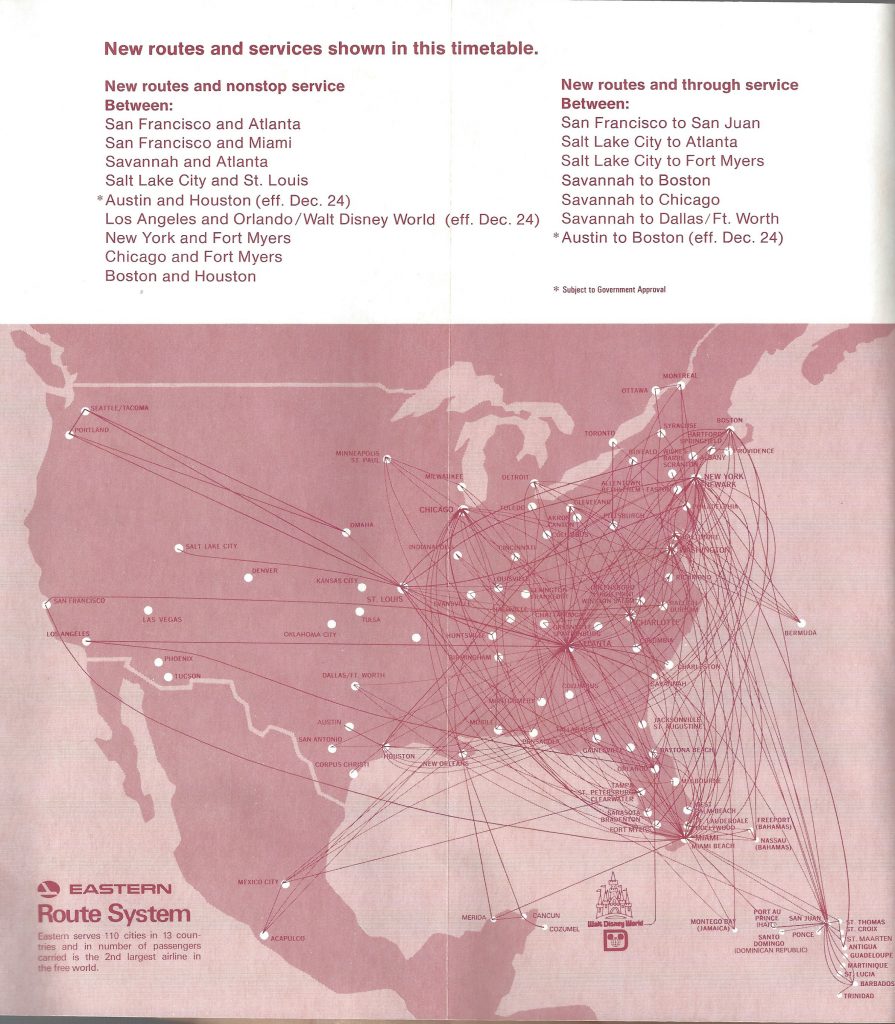

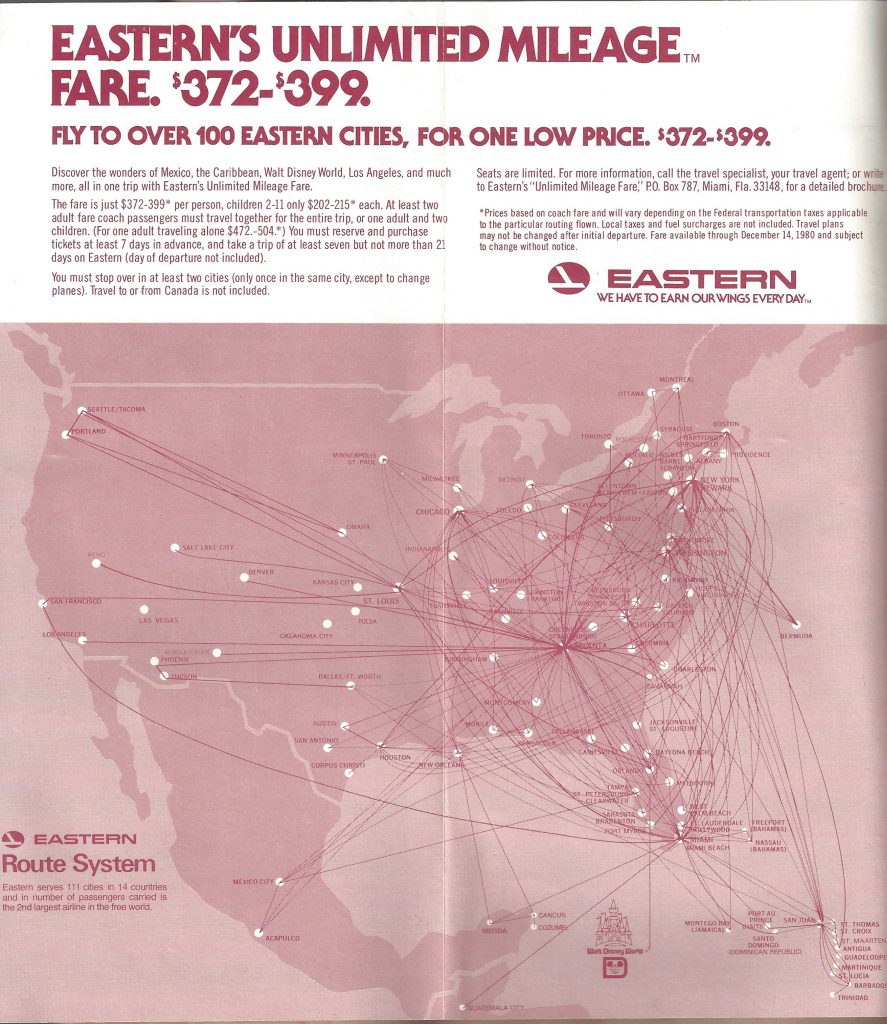

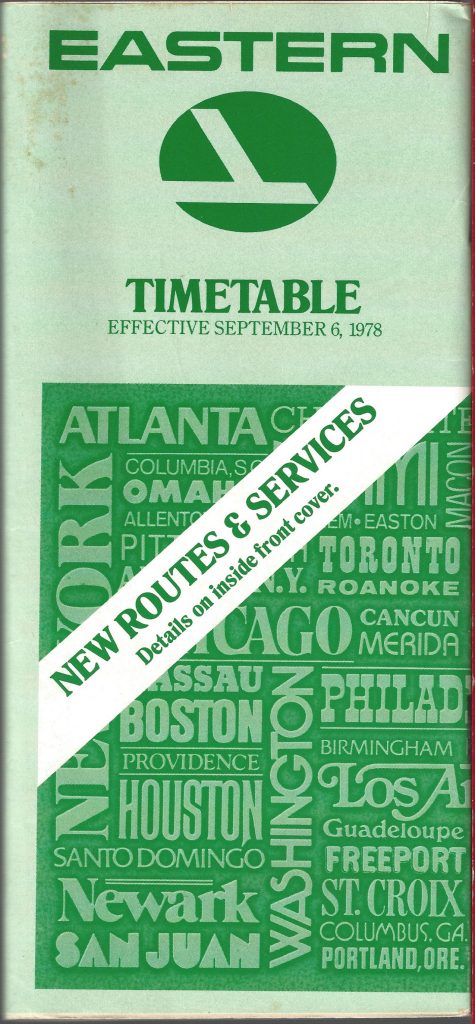

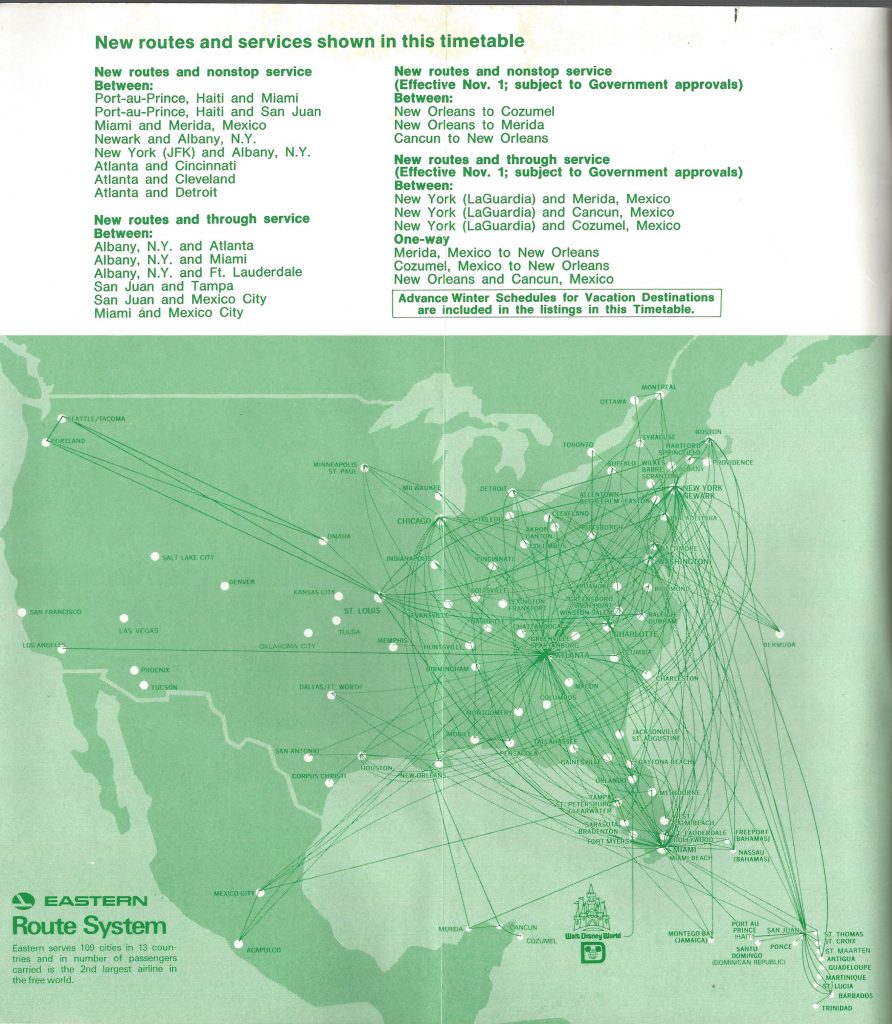

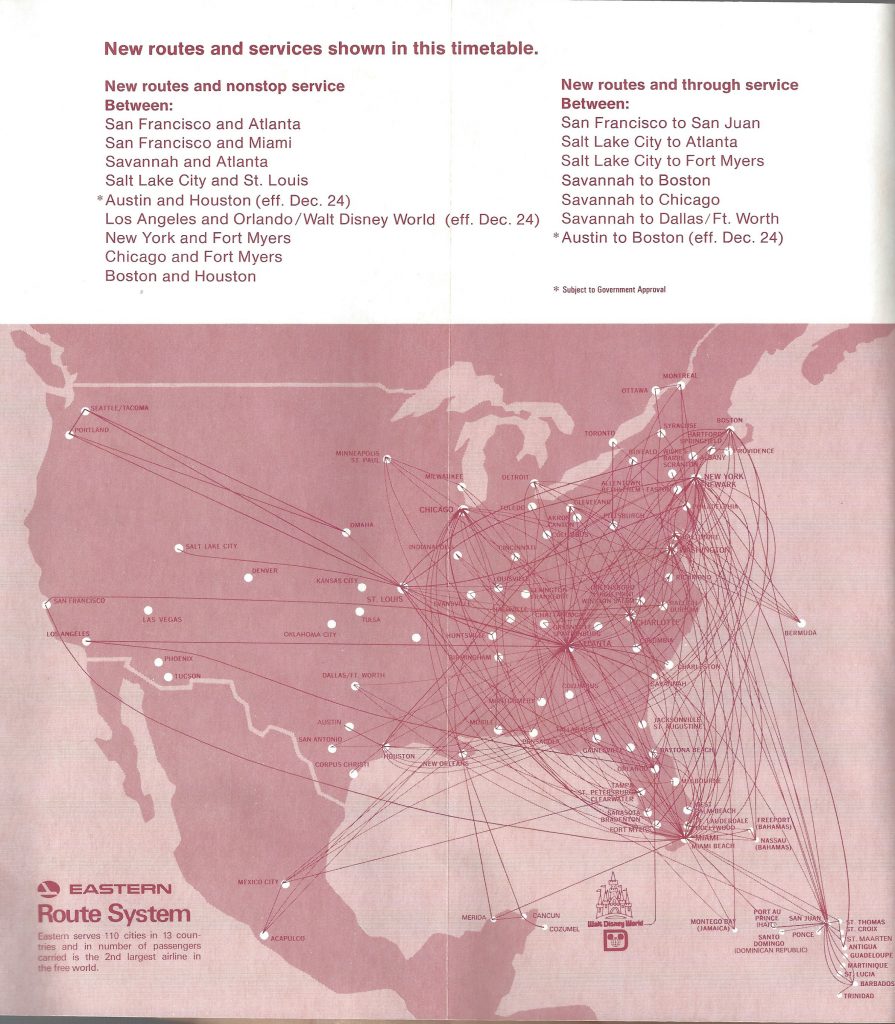

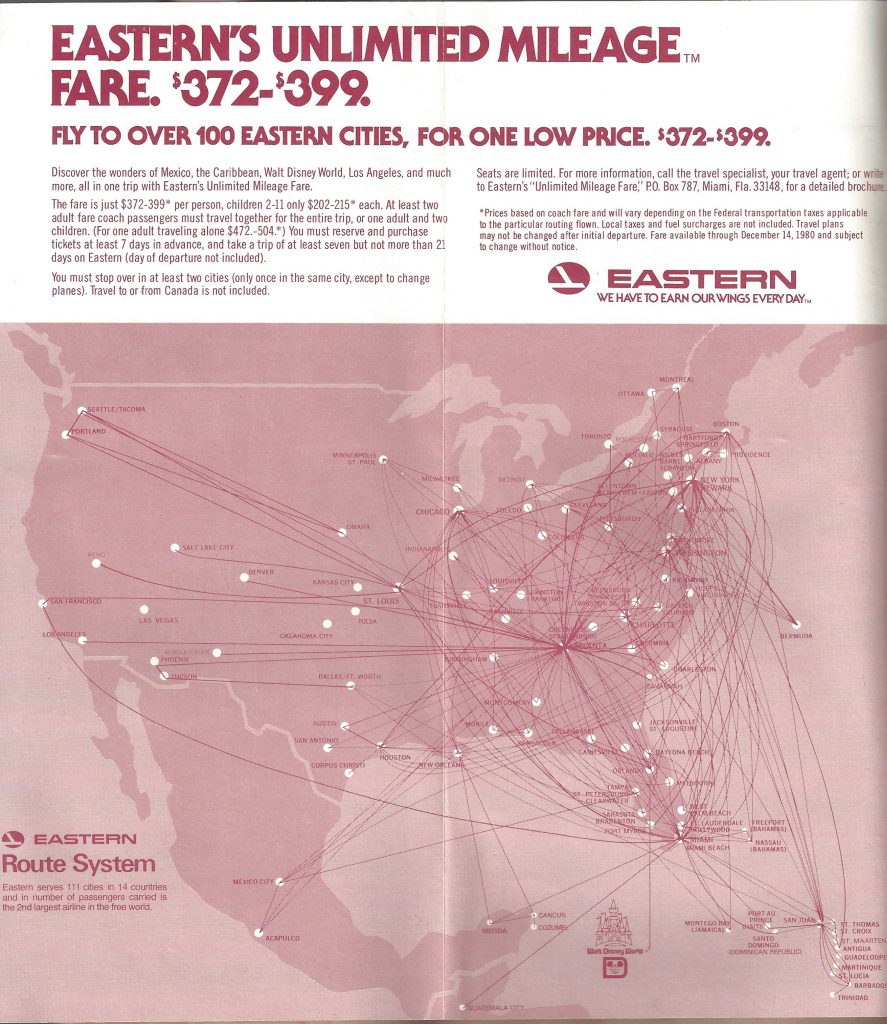

Eastern Airlines enjoyed a number of new route awards prior to the passage of the Airline Deregulation Act, and the timetable dated September 6, 1978 shows the carrier focused on bolstering its strongest markets, Atlanta, Miami, New York and San Juan. The December 13, 1978 issue, which was the first after Deregulation, shows a similar strategy, although with an increasing emphasis on secondary markets in Houston, Central Florida and St. Louis (which was becoming an east-west hub).

By the end of 1979, Eastern had tied Albuquerque, Phoenix and Tucson to its primary hub in Atlanta, and added Reno to St. Louis service. However, the Los Angeles to Orlando service started the prior winter had disappeared from the schedule.

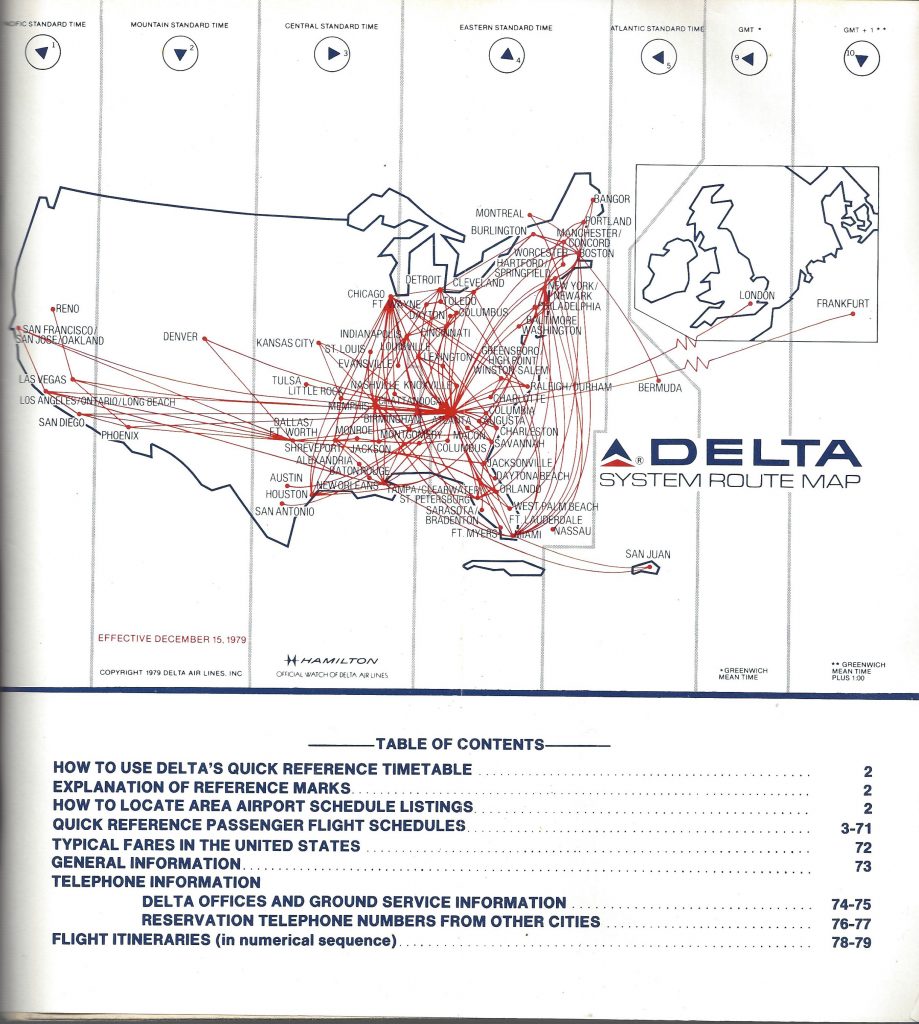

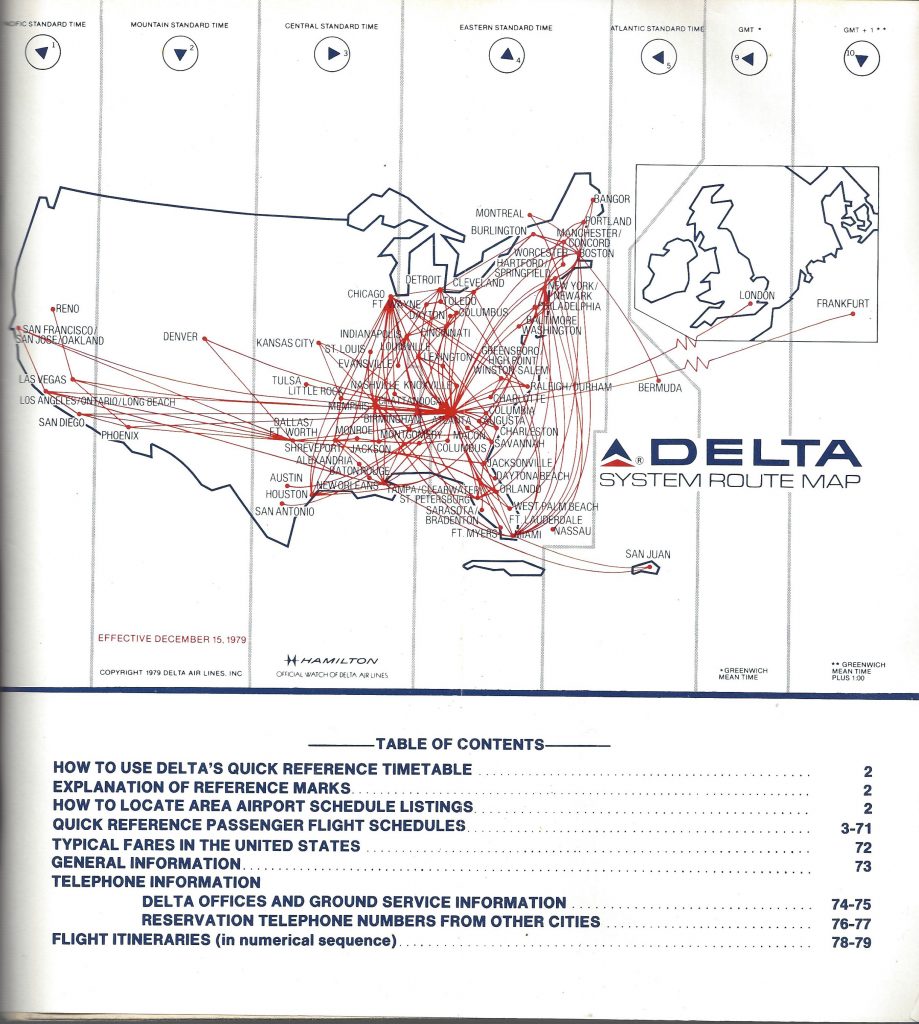

Delta Air Lines’ timetable dated December 15, 1978 shows a rather conservative strategy as it inaugurated only 5 new routes, all of which were tied to a station where the carrier already had a significant presence. DC-8-50s, which were on the verge of being phased out of the fleet, provided some of the capacity required to operate the additional flights.

The timetable from the end of the following year, dated December 15, 1979, shows Delta still operating all of those routes, with the Atlanta services up to 4-5 daily flights. The carrier had also added routes to the West from both Atlanta and Dallas/Ft. Worth.

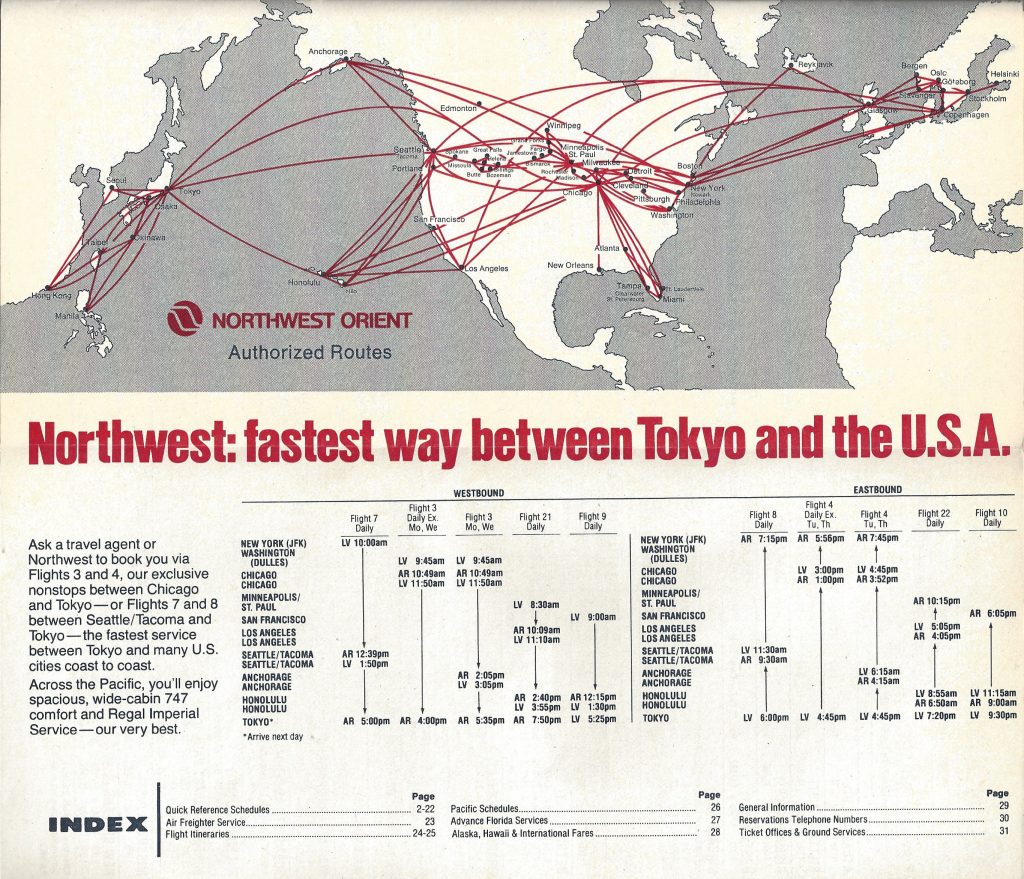

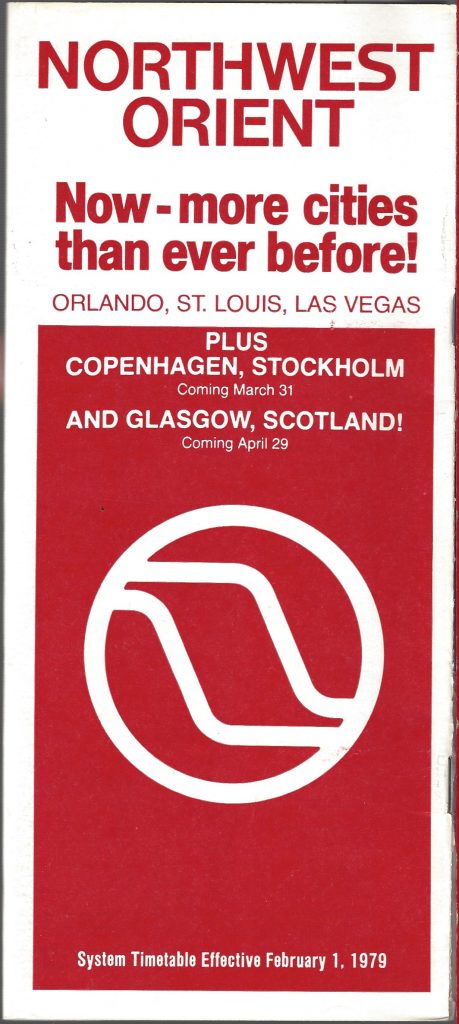

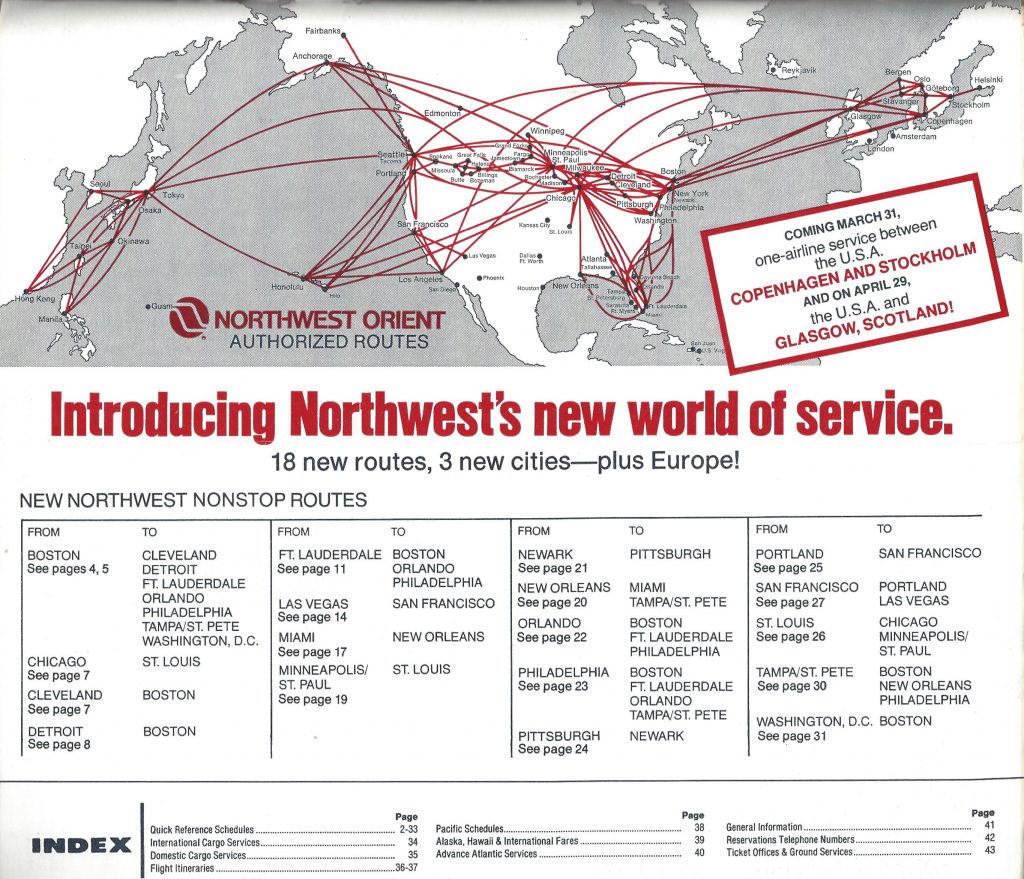

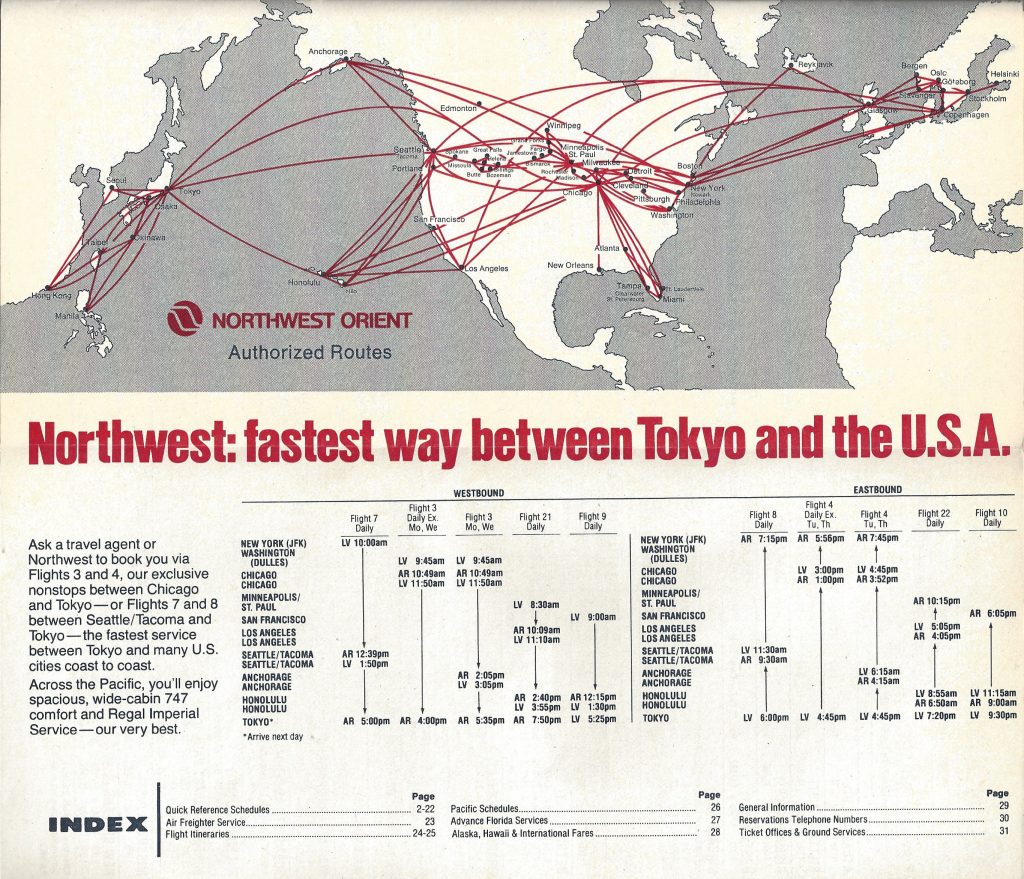

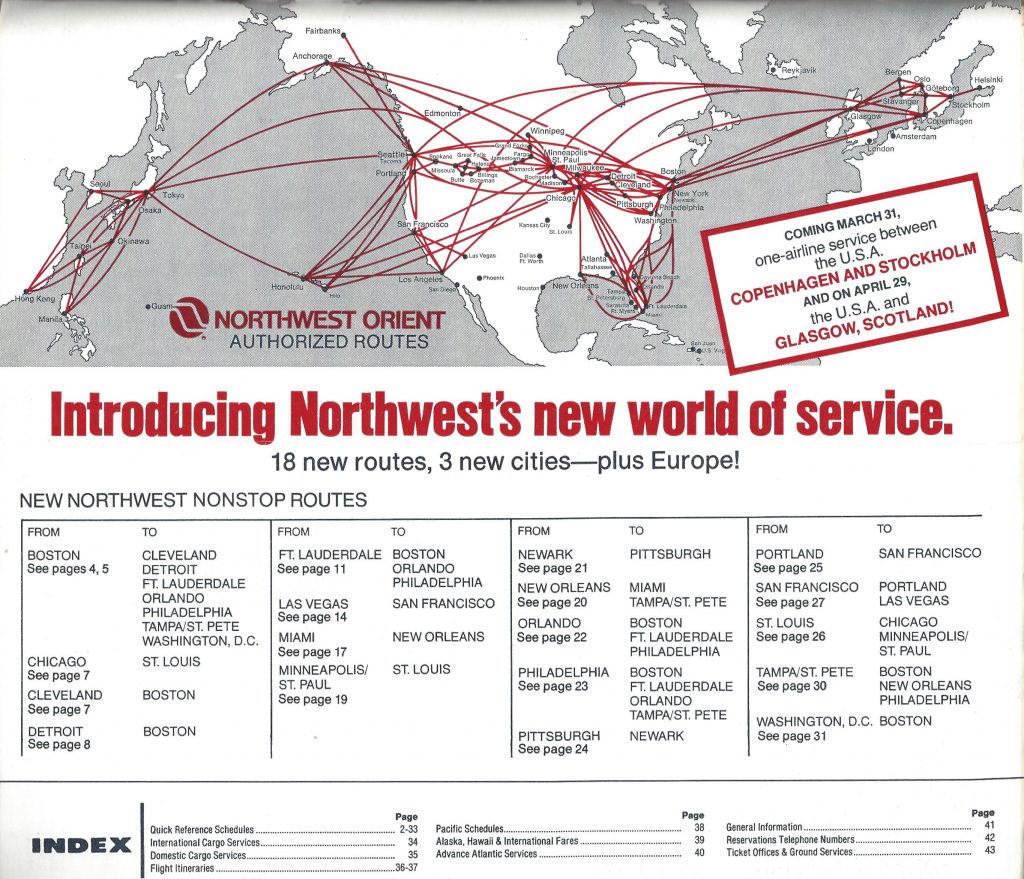

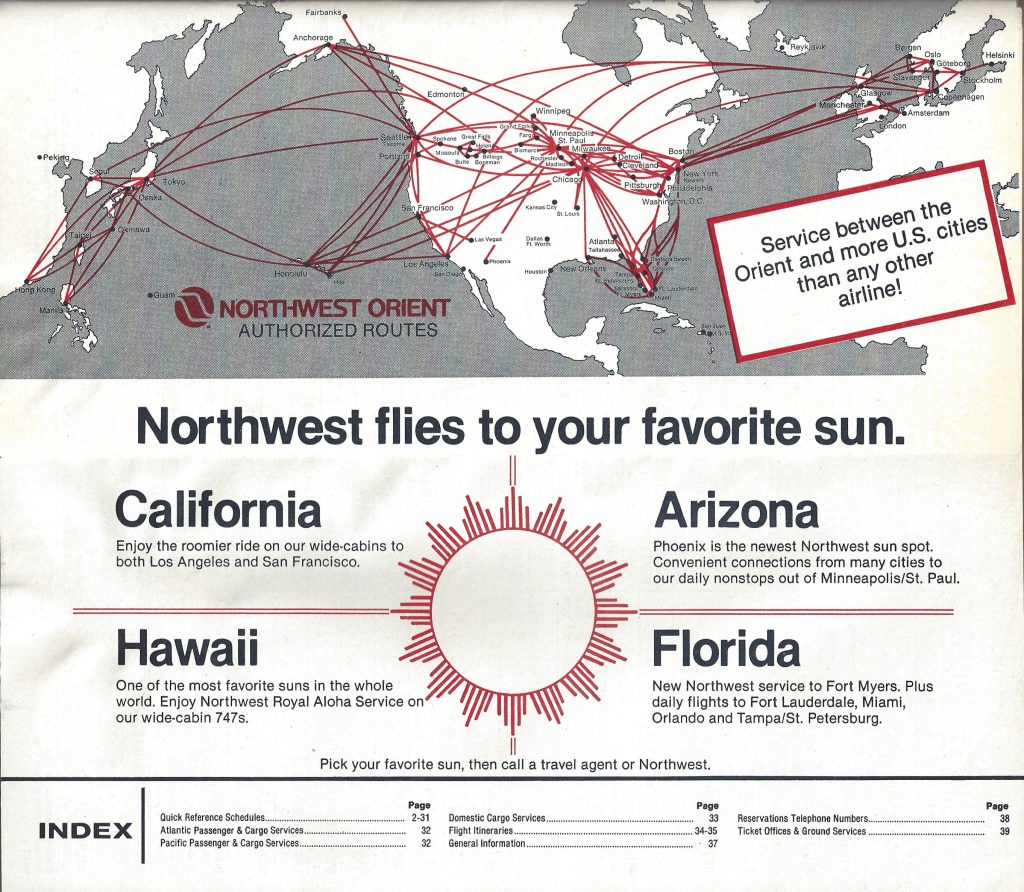

Northwest Orient Airlines added 3 new cities to its network with the timetable dated February 1, 1979, Orlando, St. Louis and Las Vegas. St. Louis was connected to Chicago and Minneapolis/St. Paul, which were 2 of Northwest’s largest stations. Orlando received service from Boston and Philadelphia (as did several other Florida cities).

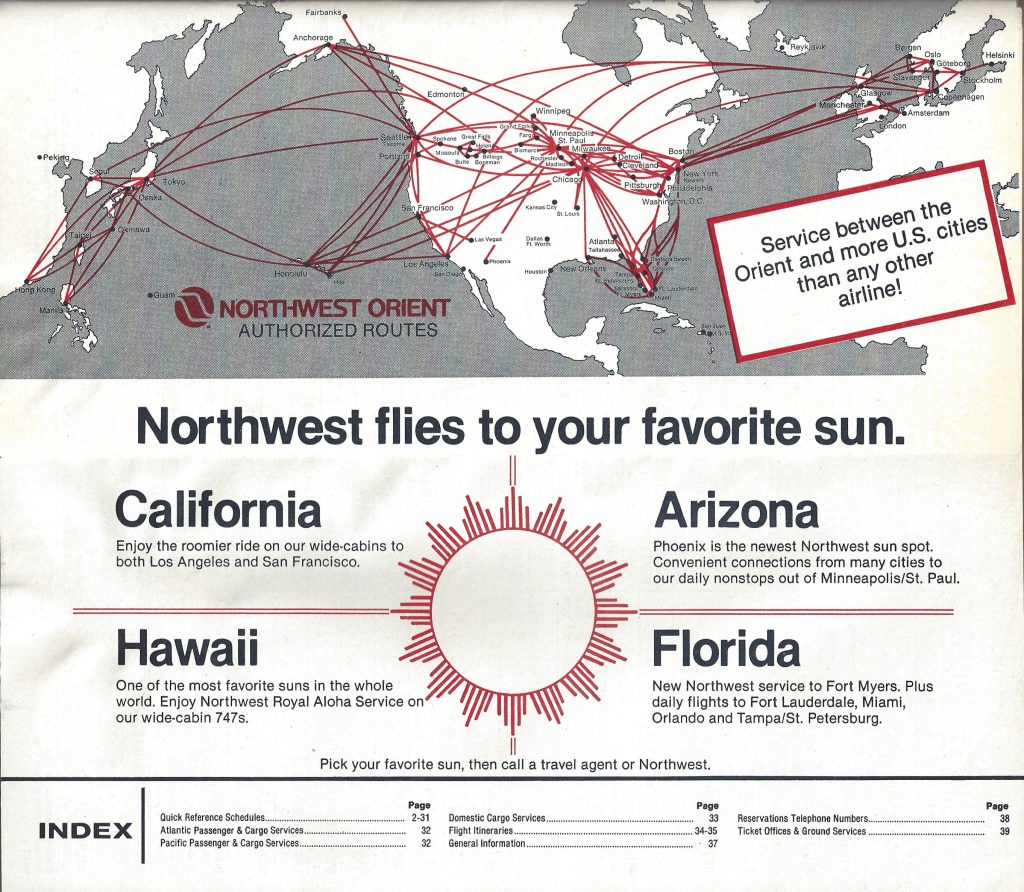

But Las Vegas was something of a head-scratcher, with once daily service to San Francisco that continued to Minneapolis/St. Paul. San Francisco was a minor station for Northwest with only 4 other daily flights, and the direct service to Minneapolis took more than twice as long as Western’s nonstop service. As illustrated by the timetable dated December 18, 1979, service to Phoenix had also been inaugurated.

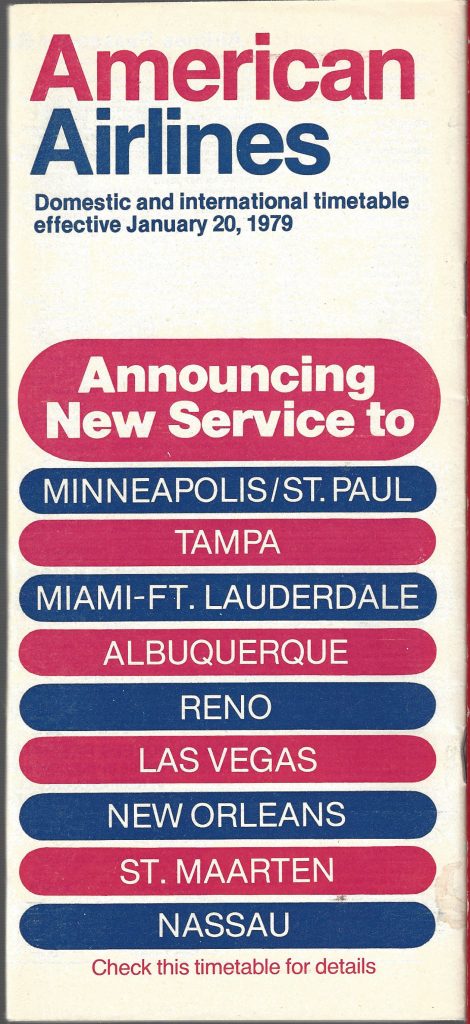

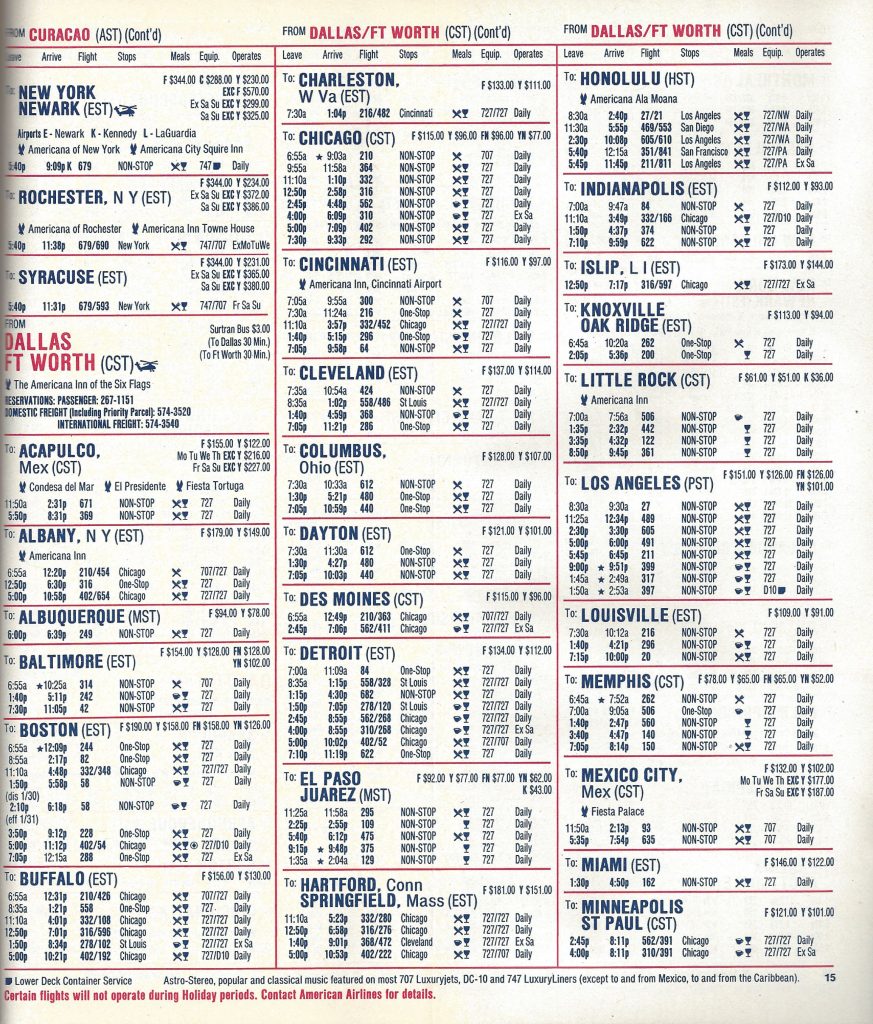

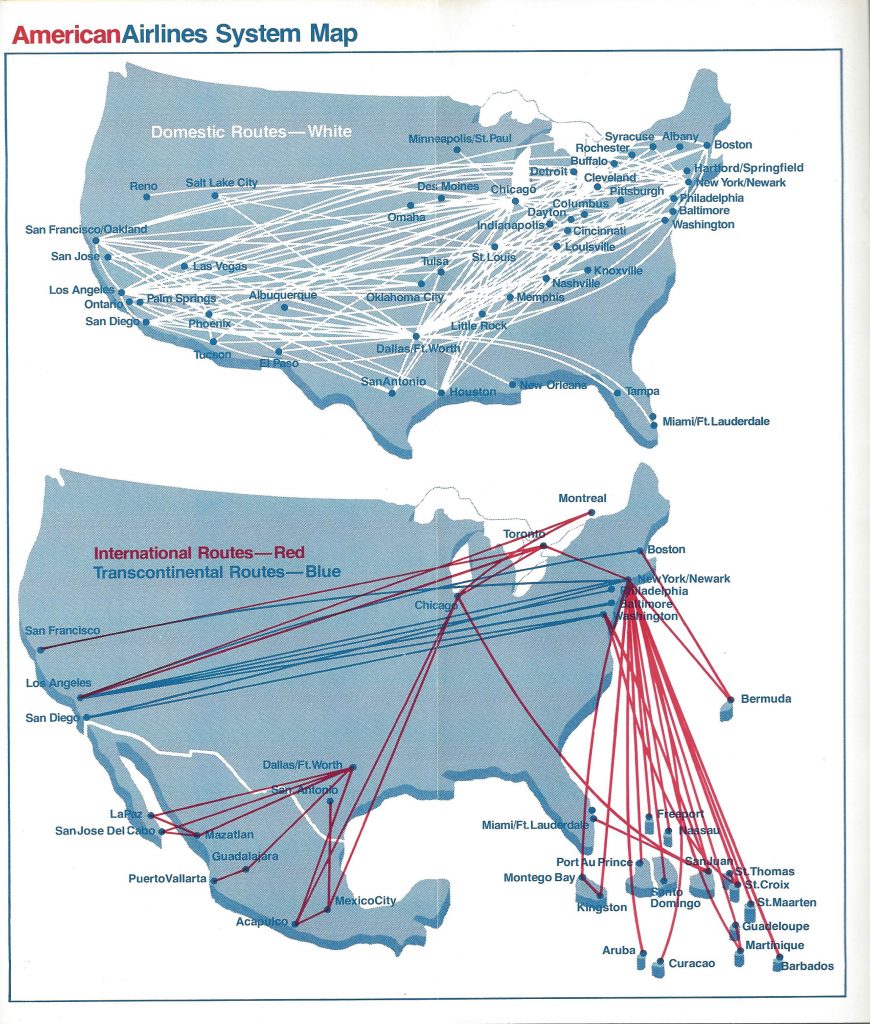

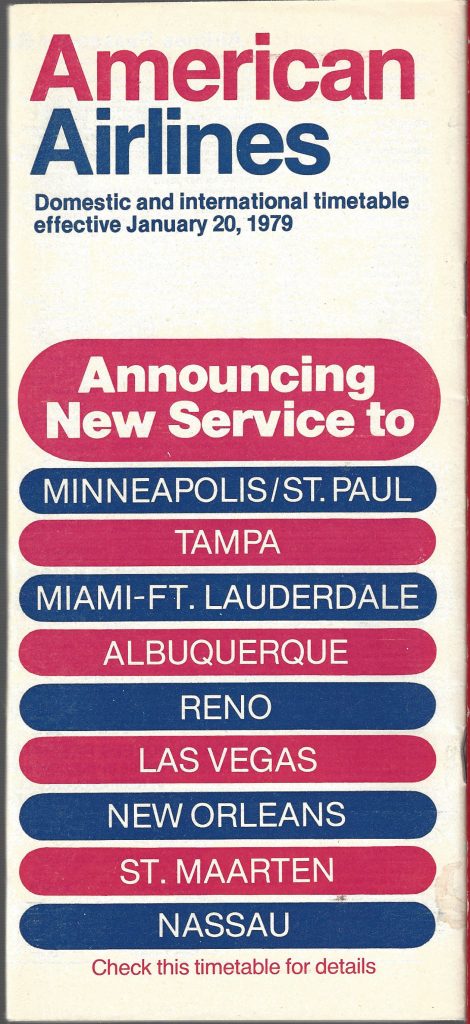

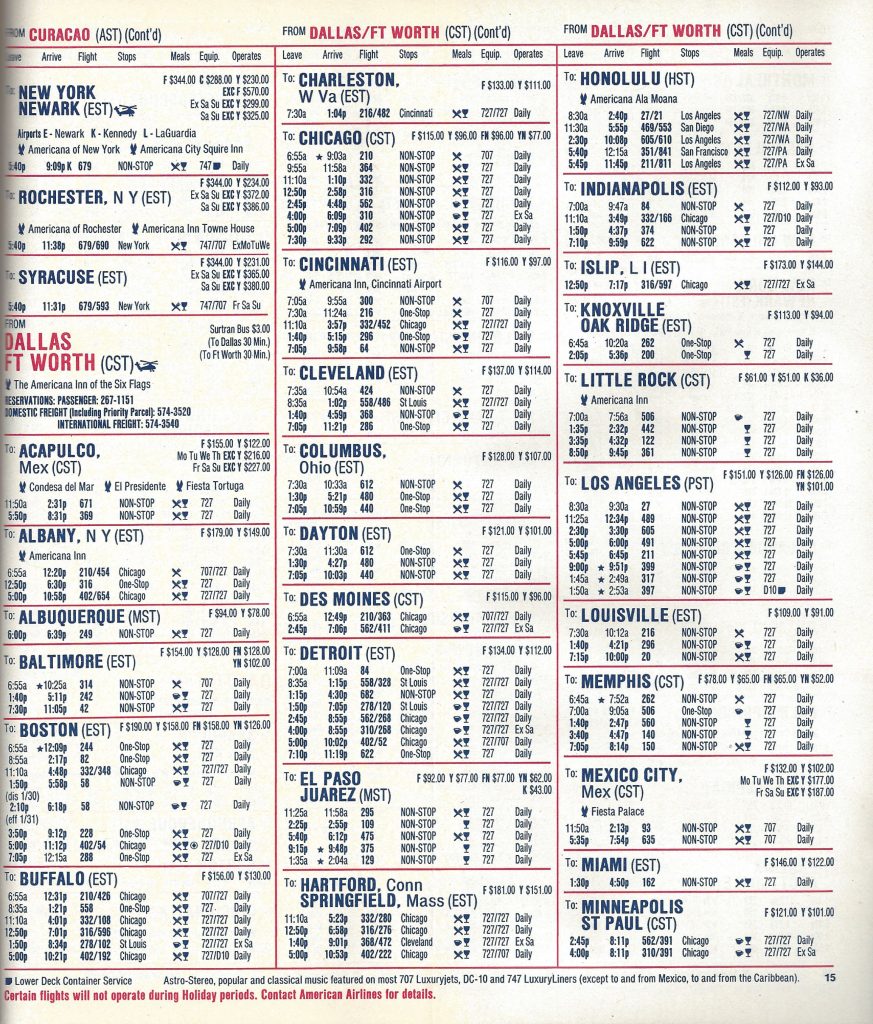

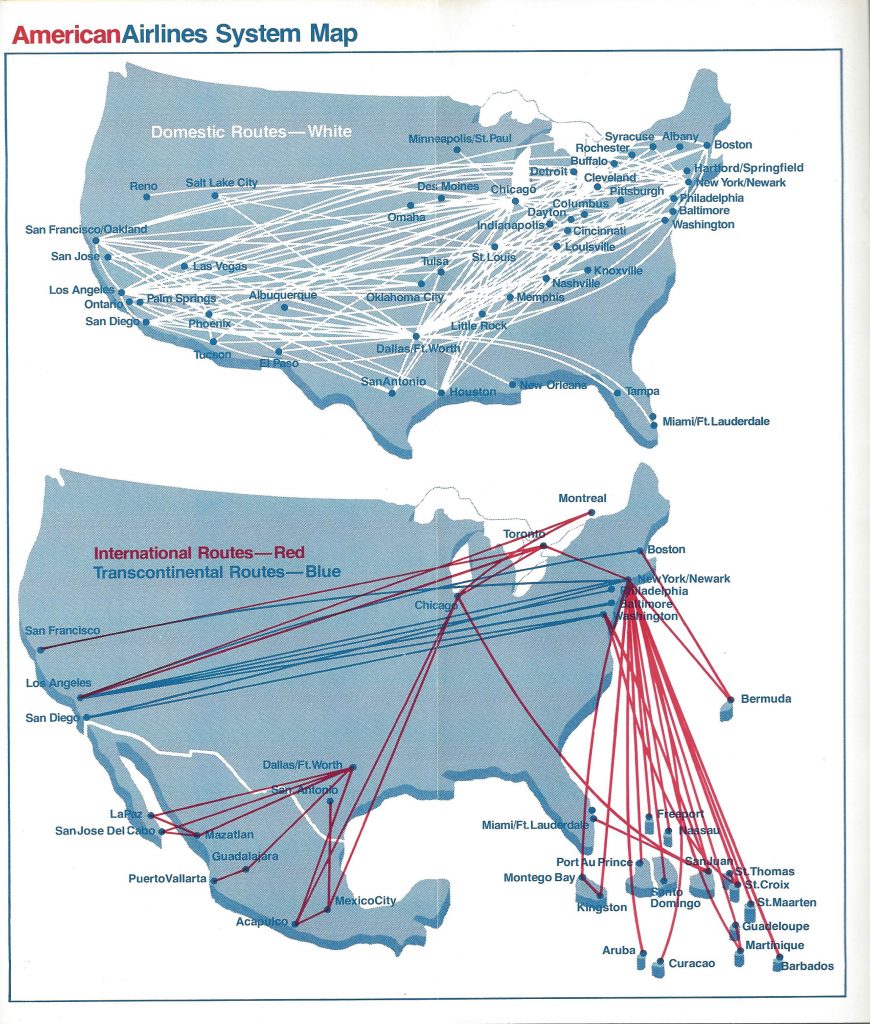

American Airlines took a more aggressive approach than most, and the timetable dated January 20, 1979 shows 9 new cities being added to its network. Most of the new stations were tied into major hubs, either with nonstop or direct service. Service was added connecting Dallas/Ft. Worth to Albuquerque, Miami, New Orleans, Reno and Tampa, while Chicago received service to Minneapolis/St. Paul.

A few new routes didn’t feed major hubs, as service was inaugurated to Las Vegas from Cleveland and Detroit, while the oddest of all was a trans-continental nonstop service from San Francisco to Miami. Unsurprisingly, the San Francisco/Miami service was already discontinued by the end of year.

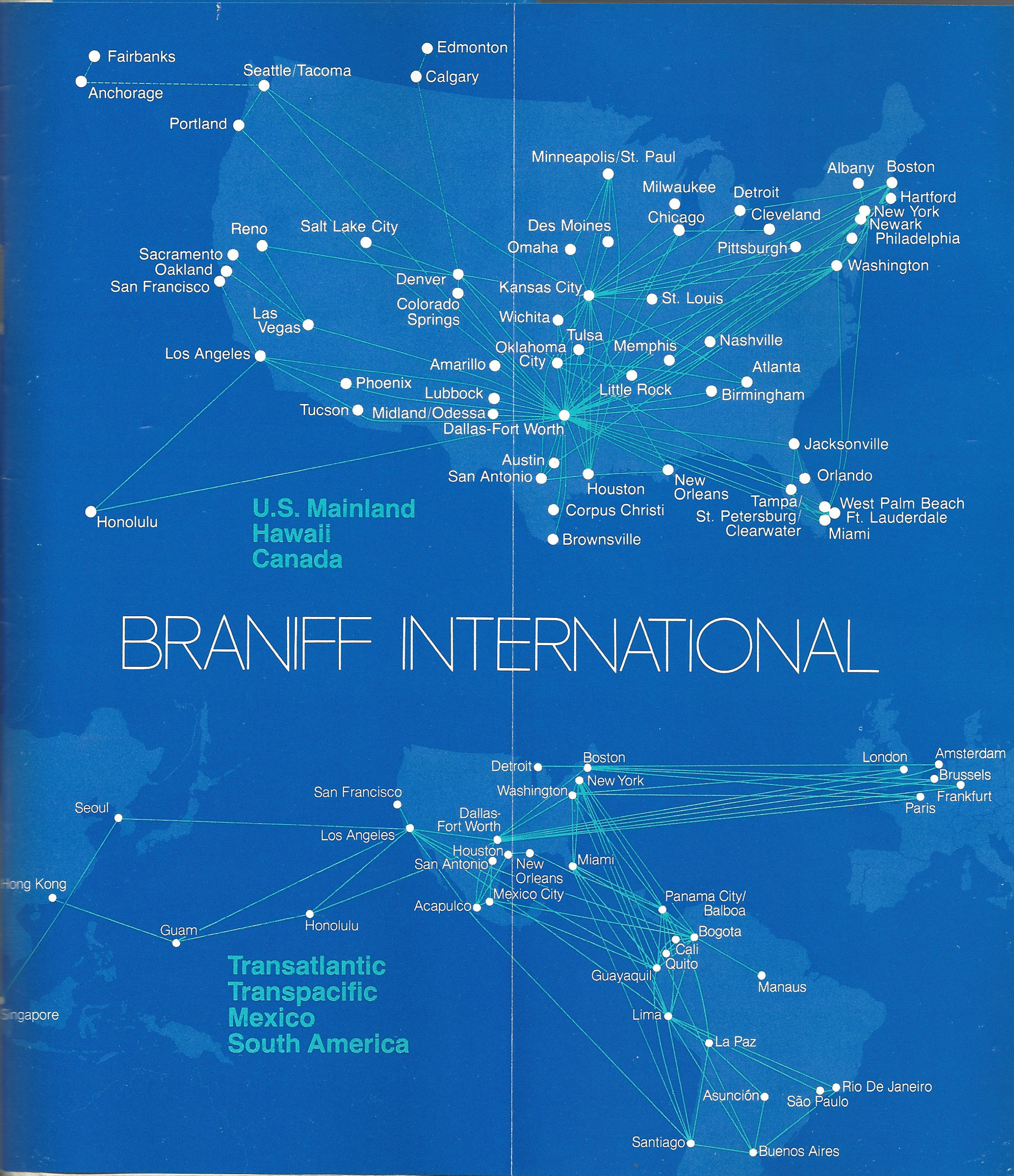

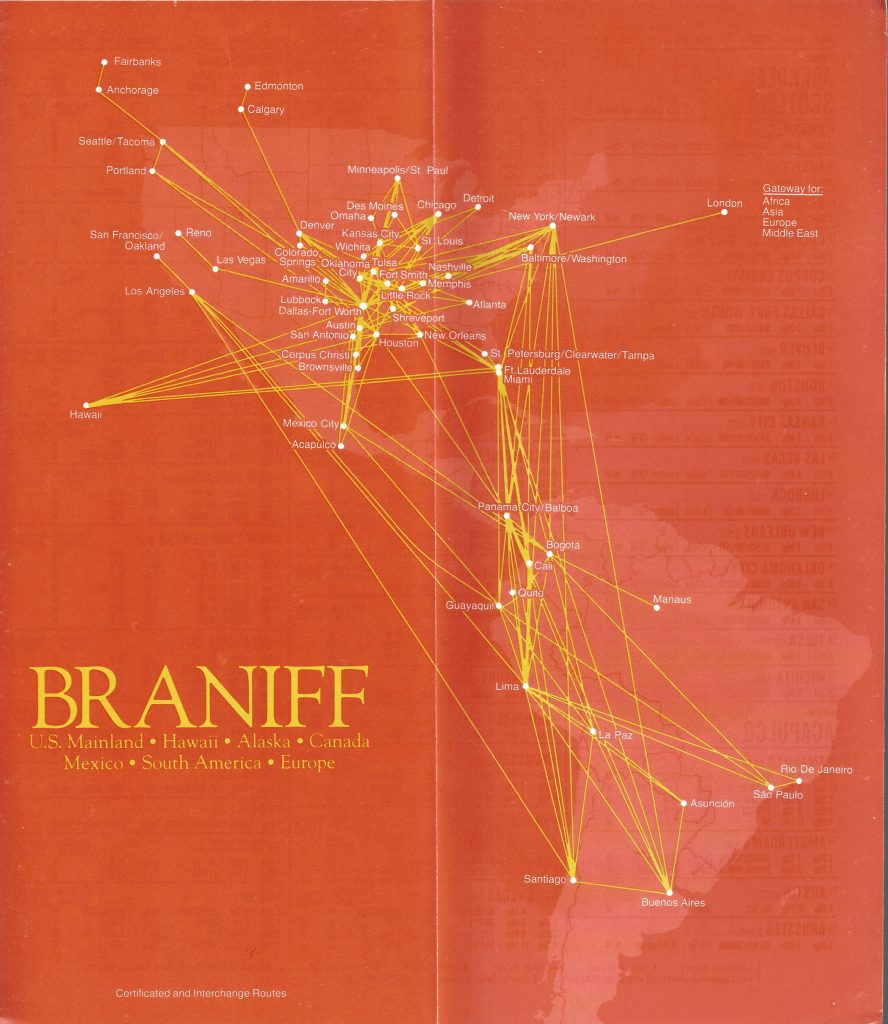

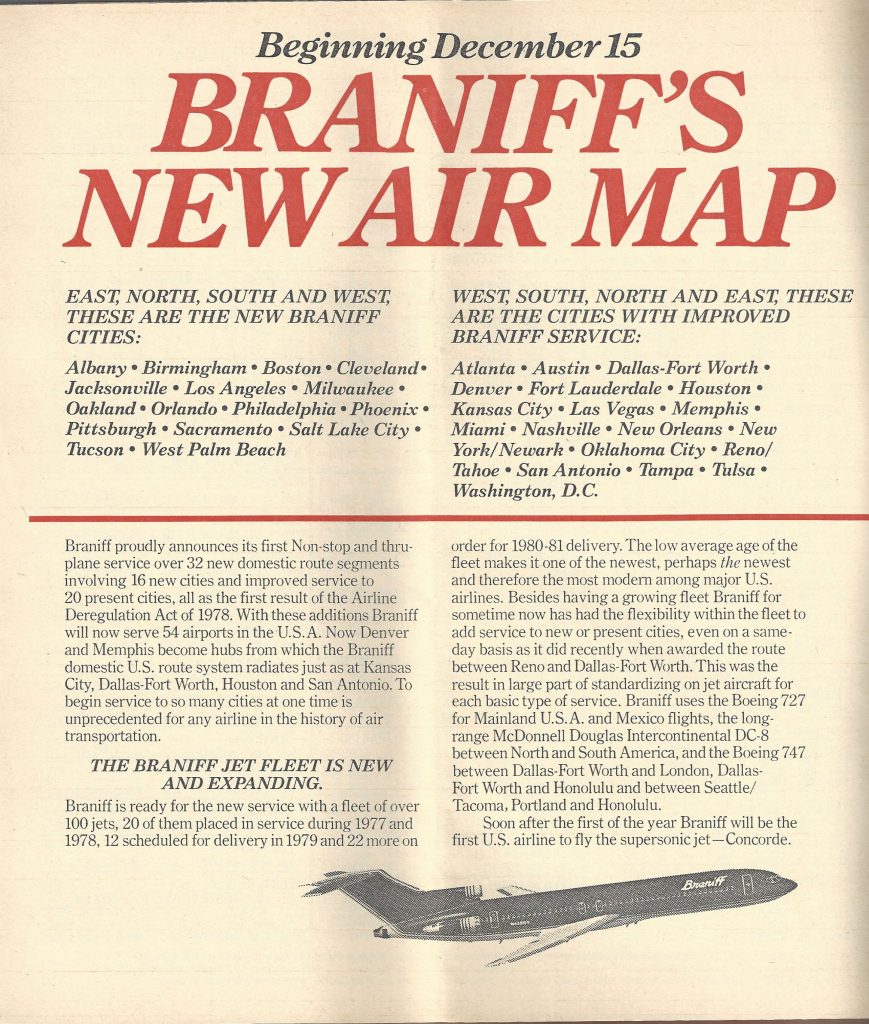

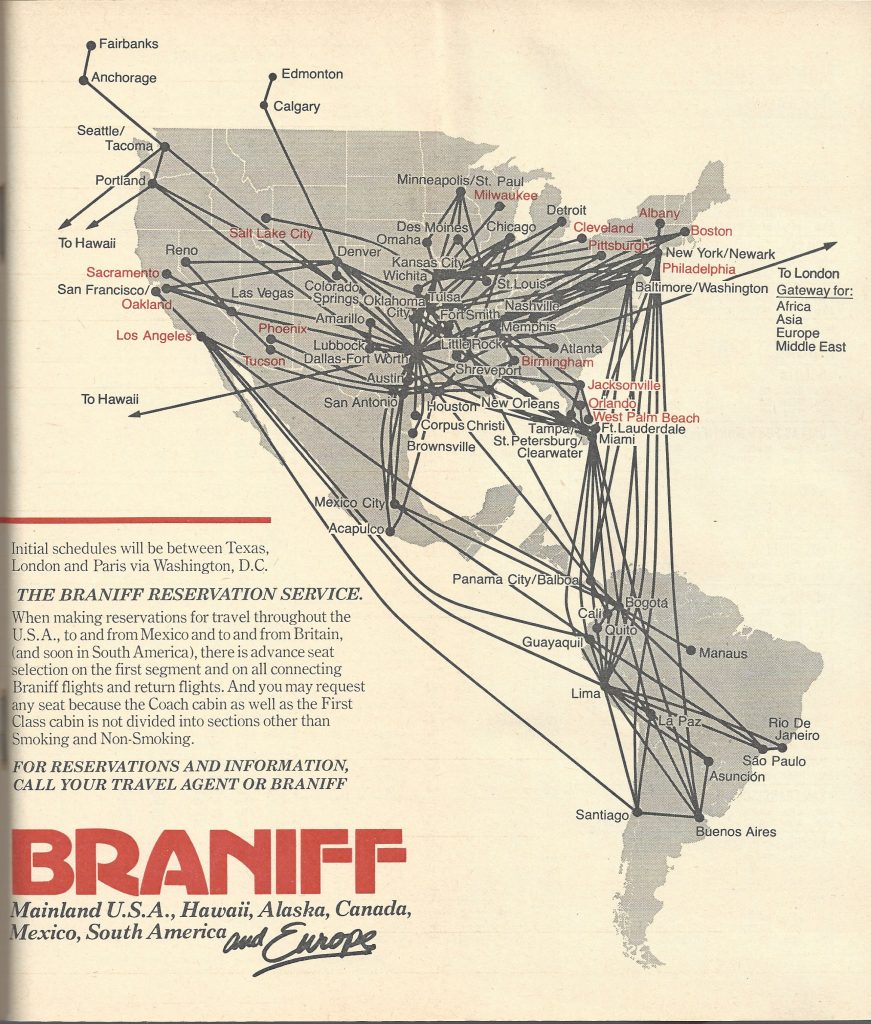

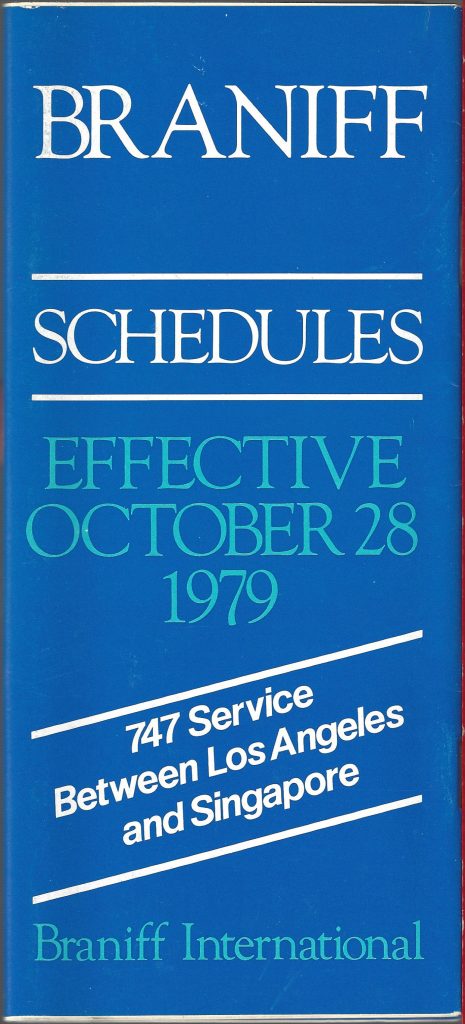

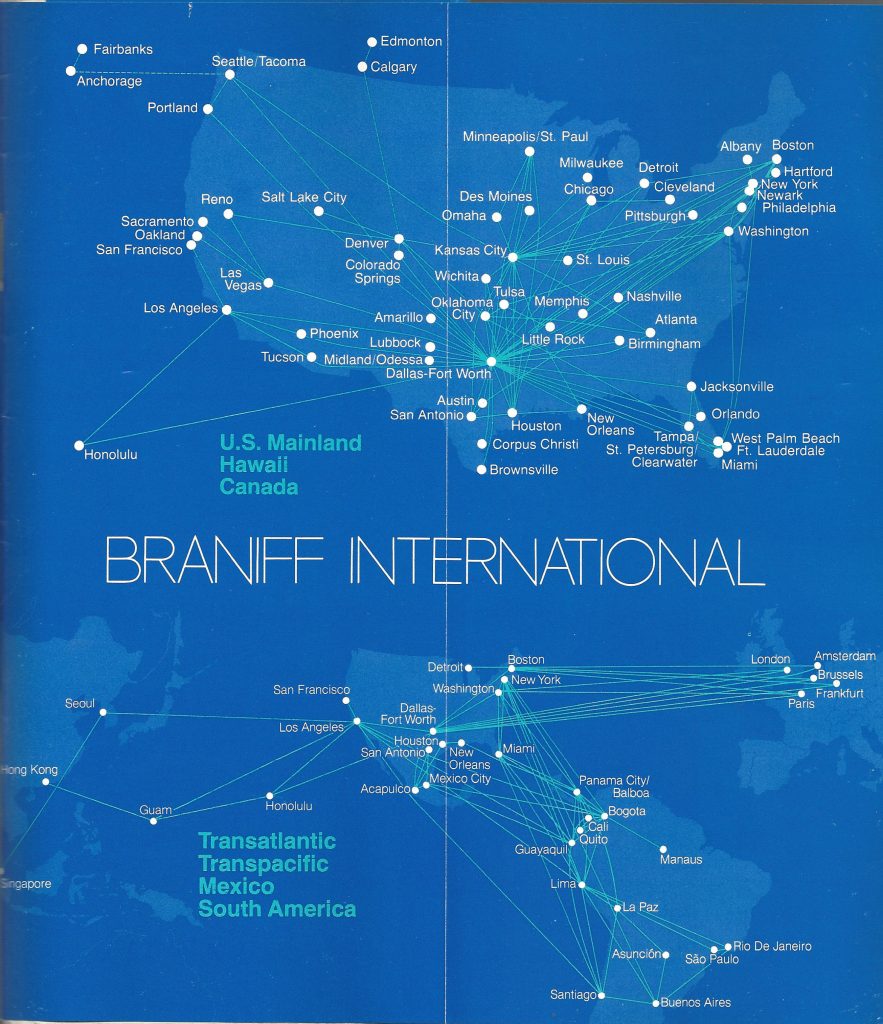

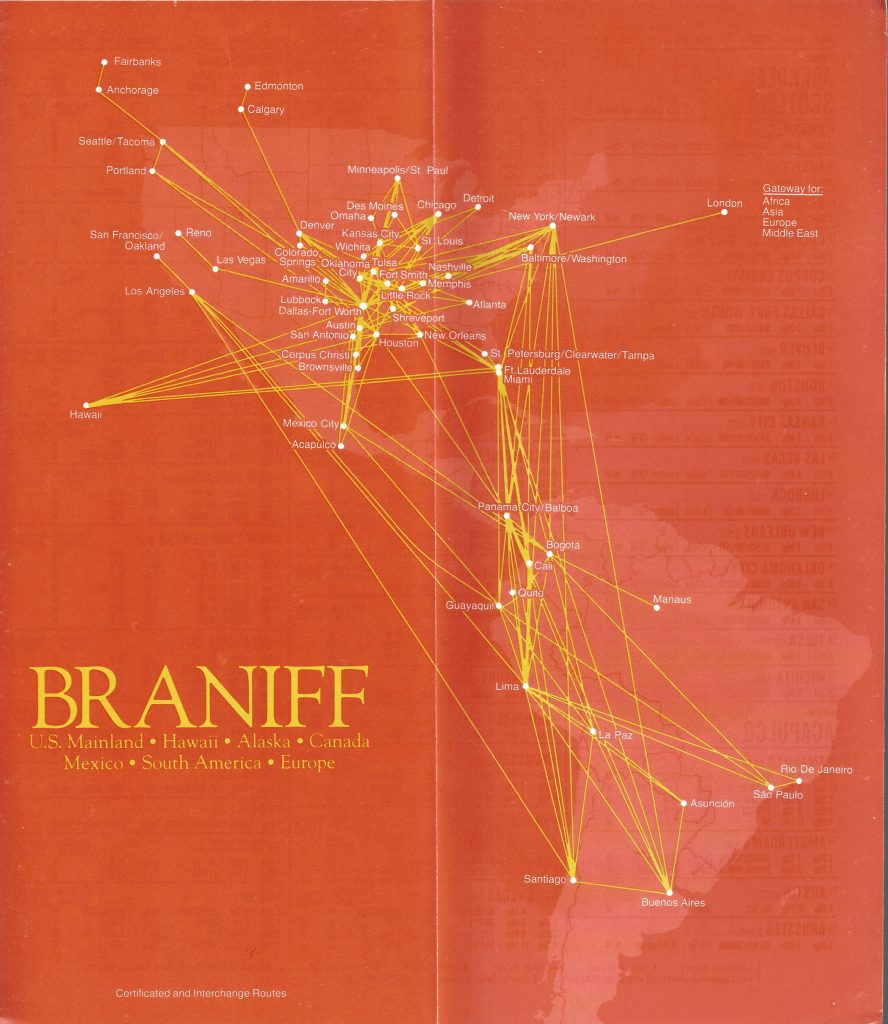

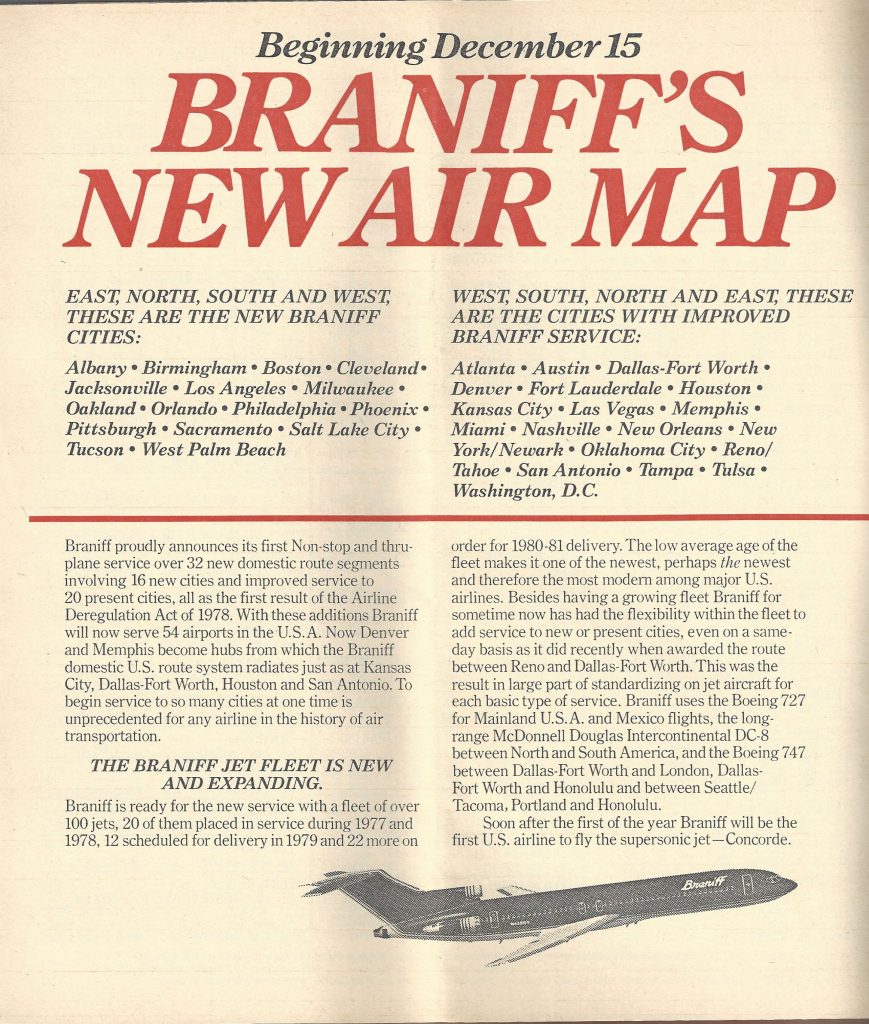

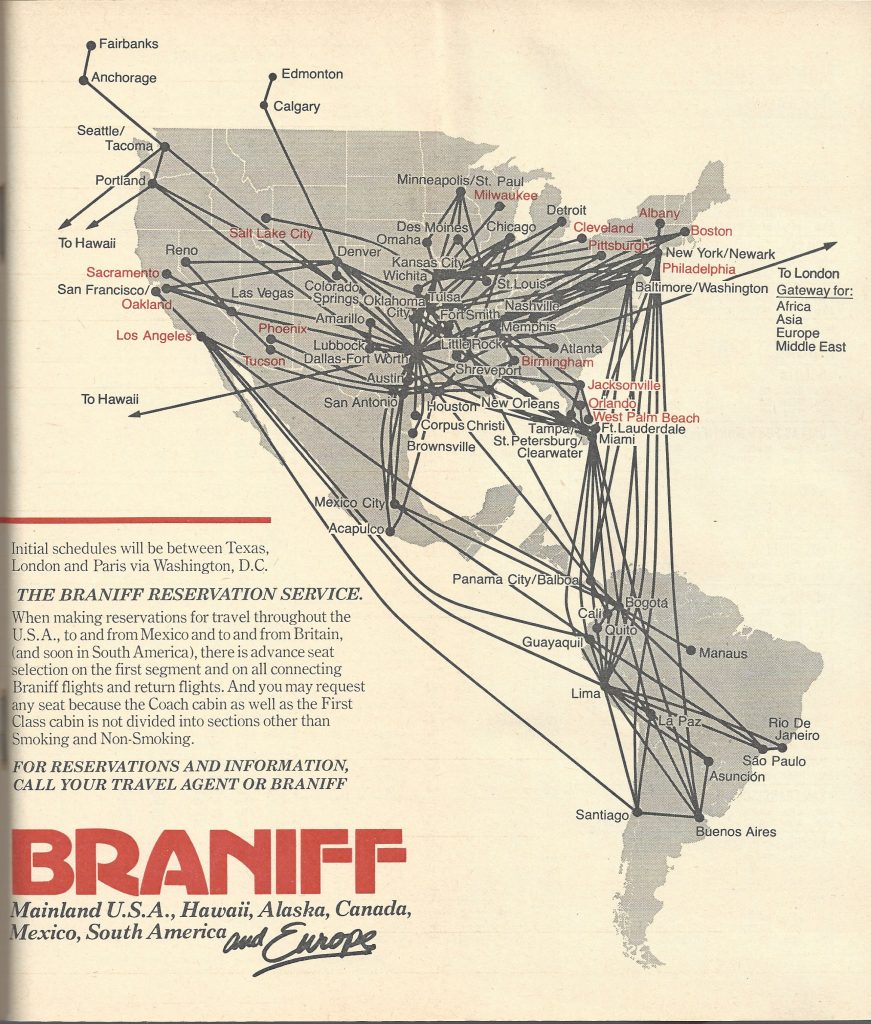

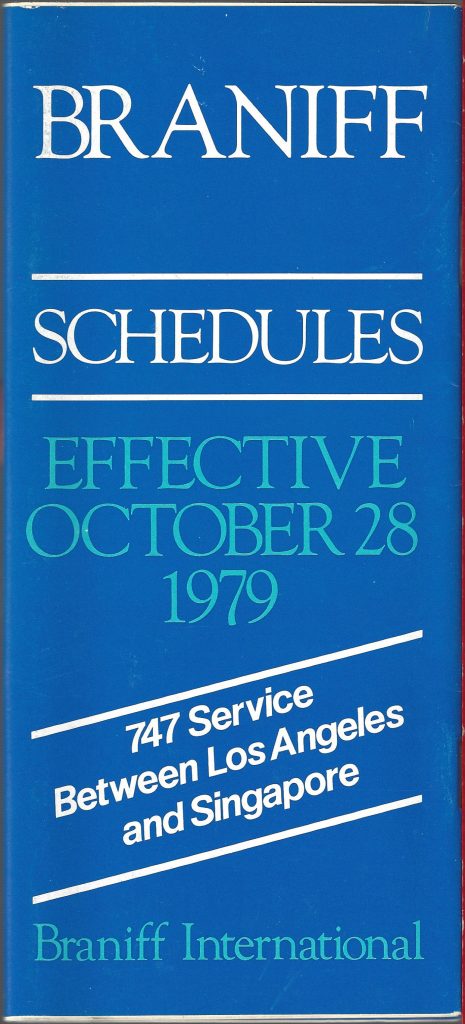

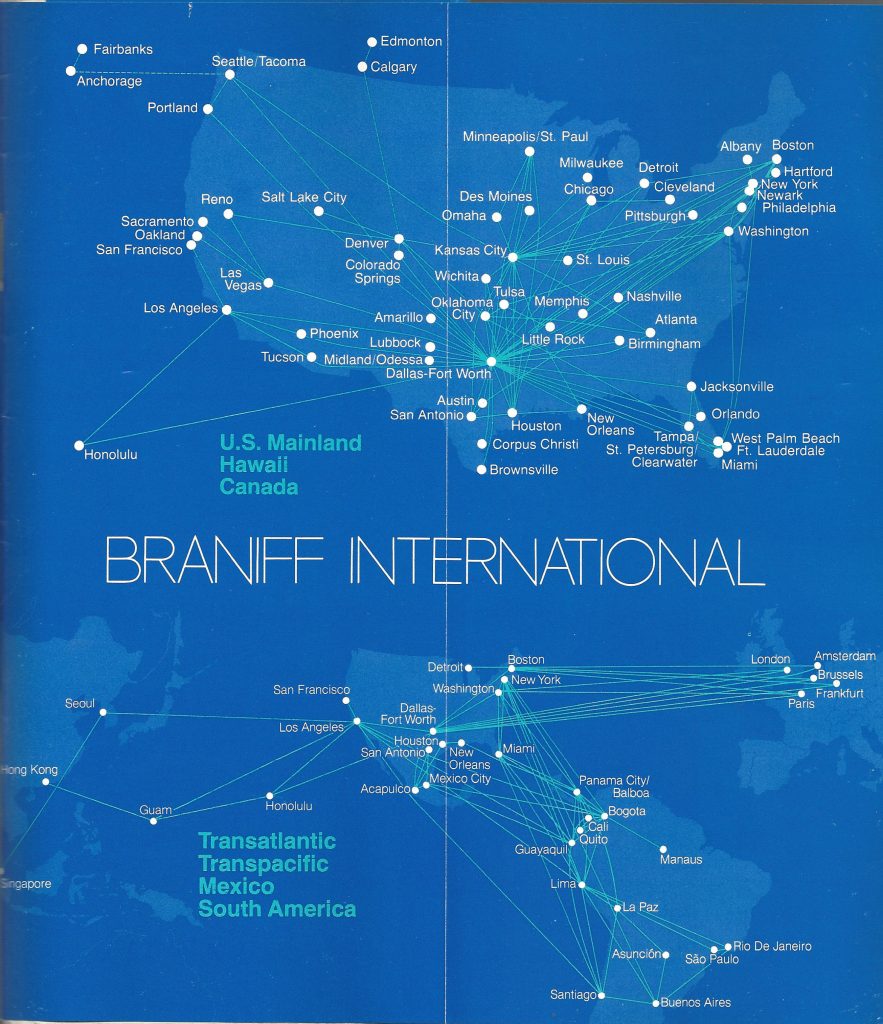

But the biggest eye-opener in the Deregulation route frenzy was Braniff International Airways, which inaugurated new service on 32 routes and opened 15 new stations with its December 15, 1978 timetable. The centerfold of this issue boasts about the new service, and claims, “to begin service to so many cities at one time is unprecedented in the history of air transportation”. (The map in the centerfold identifies Los Angeles as a new station, even though international service had been offered there for years.)

Braniff was right about its expansion being “unprecedented“. These new route requests came with a “use it or lose it” condition, and as one of the smaller trunk carriers, Braniff’s fleet was stretched thin attempting to cover 64 additional segments.

Rather than pause and allow all of this growth to be properly assimilated into the system, Braniff continued to expand in 1979, both domestically (and more importantly) internationally. The all-727 domestic fleet could not handle all of the new flights so DC-8s soon started operating domestic segments. By summer, DC-8s were operating scheduled services to stations such as Denver, Memphis, Tampa and Orlando. (The carrier would later be fined by the FAA for many hundreds of maintenance violations resulting from the demands placed on the fleet.)

Braniff ordered dozens of aircraft to support the new services, added through Concorde service from Dallas/Ft. Worth to both London and Paris (in cooperation with British Airways and Air France), created a trans-Atlantic hub in Boston (one of the cities added in December, 1978), and began operating trans-Pacific services as well. The results were predictable, and the once profitable carrier quickly faced mounting losses and declining customer service.

Routes and employees were shed rapidly but the airline had already become a poster child for those who argued that some carriers wouldn’t know how to survive in a deregulated environment. Although Braniff lasted until the spring of 1982, the foundation for its demise was laid within the first year of Deregulation.

Next: smaller airlines navigate the first year of Deregulation.

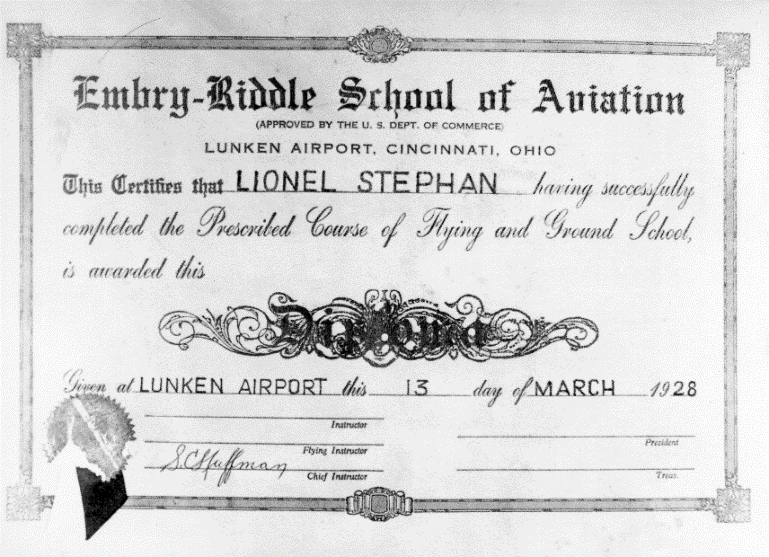

Captain Lionel “Steve” Stephan (left) at a 1985 Embry-Riddle reunion. (

Captain Lionel “Steve” Stephan (left) at a 1985 Embry-Riddle reunion. (