Reflections of Inter-New York Airport Flying

Written by Robert G. Waldvogel

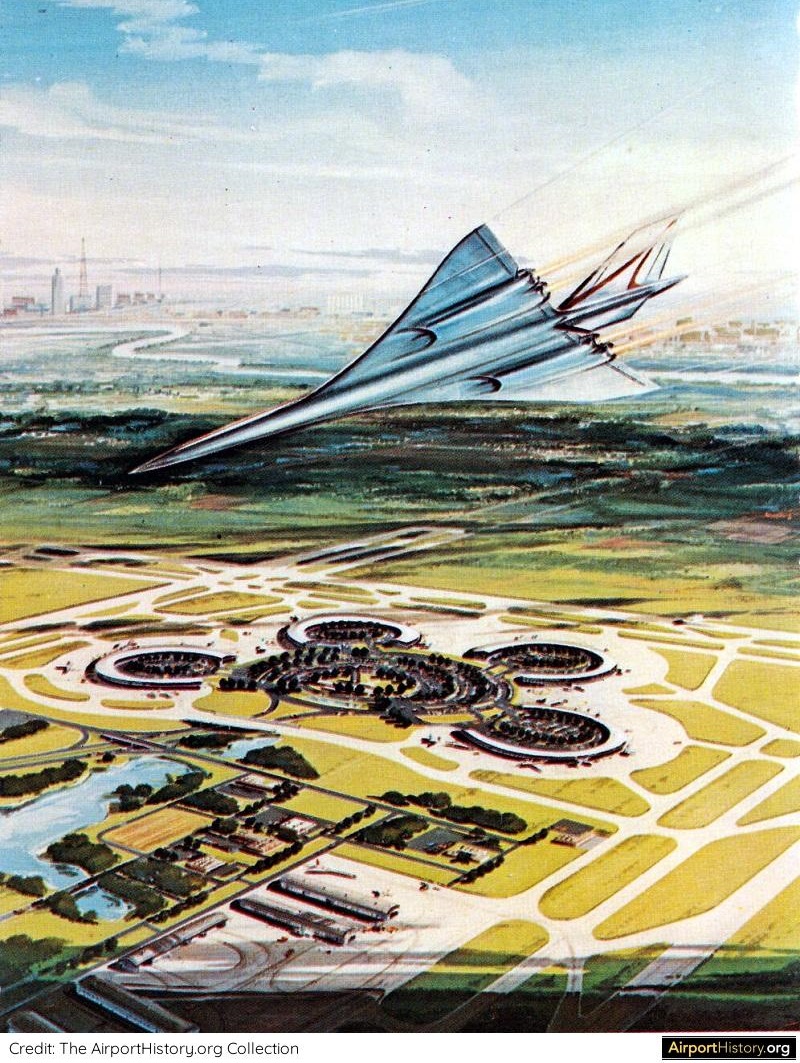

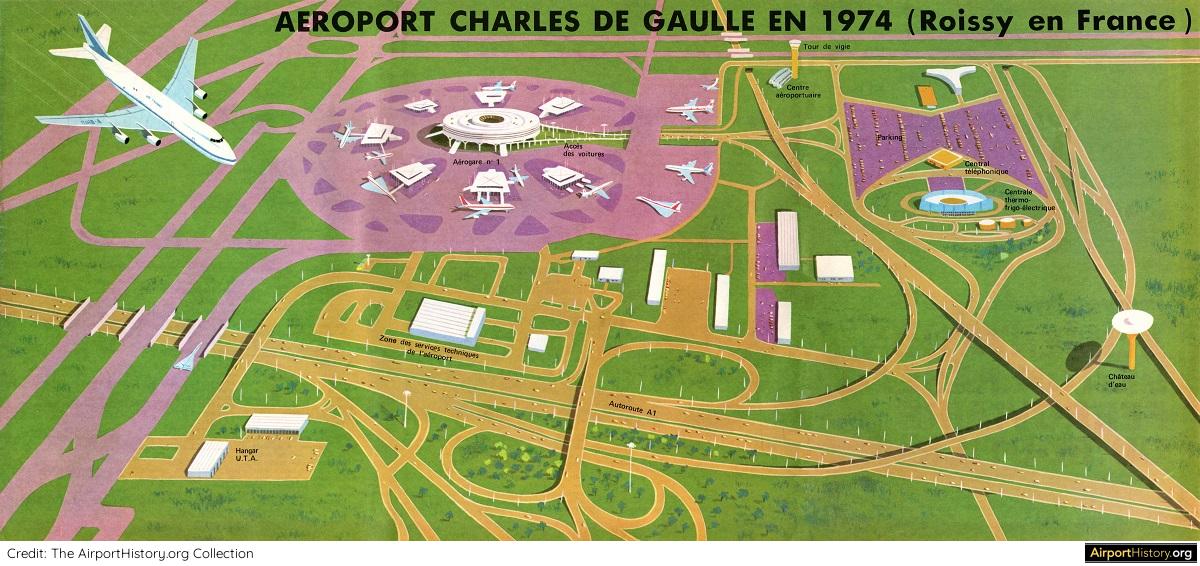

If a person about to board an airplane in Omaha were asked where he was flying to and he responded, “Omaha,” he may receive a few perplexed looks and even an audible, “But aren’t you there now?” Yet, when you live in metropolises that support multiple airports, such as New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, San Francisco, London, Paris, and Tokyo, it is possible to fly from one to the other.

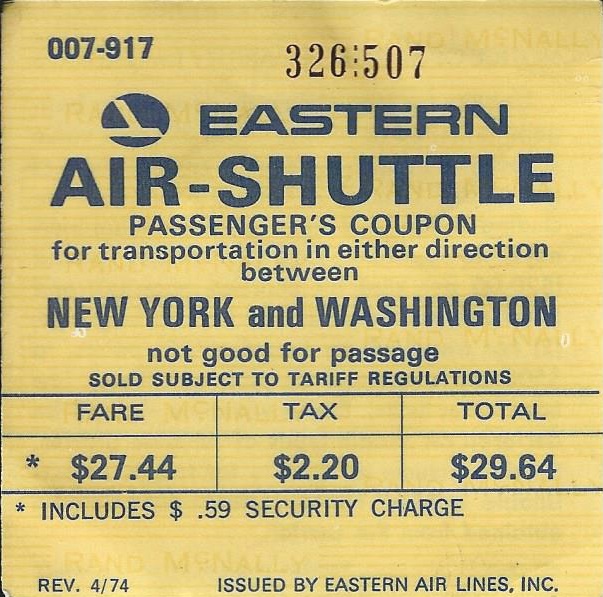

While distances between them may not be that excessive, surface travel, particularly during rush hours, can require excess time, and there is nothing like landing at an airport and proceeding to the next gate for a connecting flight and even having your checked baggage interlined to it.

New York, my hometown, qualifies as having one of these inter-airport networks. At least it has tried throughout the years, but none were successful. Aside from the obvious JFK International, La Guardia, and Newark Liberty International airports, there are secondary or satellite airfields, such as White Plains’ Westchester County and Islip’s Long Island MacArthur Airports, and even a tertiary one, Farmingdale’s Republic Airport. And all this excludes heliports.

Several fixed- and rotary-wing air shuttles were launched over the years, and a recent reflection enabled me to review the ones I took.

New York Airways, one of them, made a valiant, two-decade attempt to offer scheduled, rotary-wing service within the tri-airport network with the Boeing-Vertol V-107-II.

The type, which eventually became its flagship and virtual symbol of it, not only traces its origins to a design, but to the very, manufacturer that created it. Vertol, a Philadelphia-based, rotary-wing company, was concurrently designing two tandem-rotor helicopters—namely, the Chinook for the US Army and the CH-46A Sea Knight for the US Navy and Marines.

The latter, the result of a design competition for a Marine Corps medium assault transport, first flew in August of 1962 and was first delivered two years later, carrying troops and cargo between South China Sea positioned ships and Vietnam. Of its three prototypes, one was modified to civil V-107-II standard and it first flew on October 25, 1960, at a time when Boeing had acquired the company, resulting in the Boeing-Vertol name.

Powered by a 1,250-shp General Electric T58-8 turboshaft engine, it featured a 50-foot rotor diameter. With an 84-foot overall length, it had an 18,400-pound gross weight.

First flying in full production guise the following year, on May 19, it was FAA type-certified in January of 1962 and entered scheduled New York Airway service on July 1. The remaining ten built were sold to Kawasaki of Japan to serve as license-produced pattern aircraft, but that plan never proceeded into production.

Images of the V-107-II taking off from the Pan Am rooftop heliport symbolized skyscraper-stretching Manhattan island and formed an integral part of the city’s culture. They also represented an aspect of urban mobility: subways below its streets and helicopters above its buildings depicted successful technological triumphs over traffic-saturated streets and significantly reduced travel times.

Noise and vibration were counteracted with convenience, speed, travel times that were measured in minutes, and unparalleled views of the Statue of Liberty and the New York skyline. Approaches to the encircled “H” touchdown point on the water jutting pier placed the aircraft’s size into perspective when it was virtually swallowed by Manhattan’s monoliths during its alight.

New York Helicopter replaced New York Airways during the 1980s, although it used smaller equipment.

Owned by and operated as a subsidiary of Roosevelt Field-based Island Helicopter, it routed its Aerospatiale SA.360C Dauphin rotary-wing aircraft through the Newark, East 34th Street Heliport, and La Guardia circuit from JFK, operating from the TWA Terminal there.

Designed to replace the Alouette III, the Dauphin, with a fully glazed front nose section; a 980-shp, four-bladed Astazou XVI main rotor turbine; and a Forreston tail, first flew in prototype form on June 2, 1972. After it was retrofitted with a more powerful, 1,050-shp Astazou XVII and new rotor blades, it offered improved performance, along with lower noise and vibration levels.

The first production version, with a stepped nose, a single Turbomeca Astazou XVIIIA engine, and a 37.8-foot rotor diameter, carried eight passengers in two rows. Its maximum takeoff weight was 6,725 pounds.

Although only 34 were built because potential operators considered it underpowered, it served as the foundation of a military version, the SA.361.

One of my JFK-Newark hops entailed a short taxi to the takeoff pad amid the quad-engine widebodies that weighed some 750,000 pounds, causing the Dauphin to comparatively appear like little more than a fly. It generated lift with a full-throttle advance and was leveraged into a nose-down profile as its main rotor, biting the air at the proper angle, induced forward speed.

Escaping the air traffic-saturated maze of runways, it unrestrictedly gained altitude over Brooklyn, cruising over the azure surface of Upper New York Bay with the torch-carrying statue known as “Liberty” always in view in the distance. Making its approach to Newark International, it gently alighted, now at a nose-high angle.

Gary C. Orlando Photo

An Air Vermont JFK-Islip flight, part of a multi-sector one that continued to Hartford, Albany, and Burlington, constituted another inter-New York airport journey.

Based in Morrisville and established in 1981, it served 13 northeast cities, according to its October 1, 1983 timetable: Albany, Berlin (New Hampshire), Boston, Burlington, Hartford, Long Island, Nantucket, Newport (Vermont), New York-JFK, Portland, Washington-National, Wilkes-Barre/Scranton, and Worcester with a fleet of Piper PA-31 Navajos and Beech C99s.

The former, featuring a low wing, a conventional tail, and a retractable tricycle undercarriage, may have been “large equipment” to private operators, but it was dwarfed by the jetliners taxiing to 10,000-foot Runway 31-Left.

Not even using a tenth of it, the twin-engine aircraft surrendered to the sky and surmounted the Queens sprawl, before setting an easterly course and closing the 40-mile gap to Long Island MacArthur in as many minutes.

After a landing and a short taxi to its original oval-shaped terminal, I immediately understood why one of the scenes from the original Out-of-Towners movie was filmed there: it exuded a quiet, hometown atmosphere, especially after the JFK congestion.

Aside from JFK International Airport’s rotary-wing links to Newark, Islip’s Long Island MacArthur provided its own in the form of Continental Express, operated by Britt Airways, whose codeshare agreement enabled passengers to connect to Continental’s mainline flights. It operated ATR-42-300s.

Following the latest intra-European cooperation trend, the French Aerospatiale and Italian Aeritalia aerospace firms elected to collaborate on a regional airliner that combined design elements of their respective, once-independent AS-35 and AIT-230 proposals.

Re-designated ATR-42—the letters representing the French “Avions de Transport Regional” and the Italian “Aerei di Transporto Regionale” and the number reflecting the average seating capacity—the high-wing, twin-turboprop, cross of Loraine tail, was powered by two 1,800-shp Pratt and Whitney Canada PW120 engines when it first flew as the ATR-42-200 on August 16, 1984. The production version, the ATR-42-300, featured up-rated, 2,000-shp powerplants.

Of modern airliner design, it accommodated up to 49 four-abreast passengers with a central aisle, overhead storage compartments, a flat ceiling, a galley, and a lavatory.

Granted its French and Italian airworthiness certificate in September of 1985 after final assembly in Toulouse, France, it entered scheduled service four months later on December 9 with Air Littoral. With a 37,300-pound maximum takeoff weight, it had a 265-knot maximum speed at a 25,000-foot service ceiling.

Continental Express operated four round-trips between Islip and Newark, parking at a Terminal C gate for convenient connections to Continental’s jet flights.

Attempting to establish a link between Farmingdale and Newark International itself, PBA Provincetown Boston Airlines commenced shuttle service with Embraer EMB-110 commuter aircraft, connecting Long Island by means of a 30-minute aerial hop with up to five daily round-trips and coordinating schedules with PEOPLExpress Airlines. It stressed its convenience in advertisements—namely, avoidance of the excessive drive-times, parking costs, and longer check-in requirements otherwise associated with larger-airport usage, and it offered through-fares, ticketing, and baggage check to any PEOPLExpress final destination.

According to its June 20, 1986 Northern System timetable, it offered Farmingdale departures at 07:00, 09:50, 12:00, 14:45, and 17:55.

The EMB-110 itself was a low-wing aircraft.

Named after the Brazilians who explored and colonized the western portion of the country in the 17th century, the conventional design, with two three-bladed turboprops and a retractable tricycle undercarriage, accommodated between 15 and 18 passengers. It was the first South American commercial aircraft to have been ordered by European and US carriers.

Originally sporting circular passenger windows and powered by PT6A-20 engines, it entailed a three-prototype certification program, each aircraft respectively first taking to the air on October 28, 1968, October 19, 1969, and June 26, 1970. Although initially designated the C-95 when launch-ordered by the Brazilian Air Force (for 60 of the type), the EMB-110 was certified two years later on August 9.

Powered by PT6A-27 engines, production aircraft featured square passenger windows, a 50.3-foot wingspan, a forward, left air stair door, and redesigned nacelles so that the main undercarriage units could be fully enclosed in the retracted position.

Designated EMB-110C and accommodating 15, the type entered scheduled service with Trans Brasil on April 16, 1973 and it was integral in filling its and VASP’s feederline needs.

Six rows of three-abreast seats with an offset aisle and 12,345-pound gross weights characterized the third level/commuter EMB-110P version, while the longer fuselage EMB-110P2, first ordered by French commuter carrier Air Littoral, was powered by up-rated, 750-shp PT6A-34s and offered seating for 21.

While load factors failed to support PBA’s 19-seat EMB-110s from Farmingdale to Newark, it continued to operate the service with smaller Cessna C-402s.

First flying on August 26, 1965, the low-wing, retractable undercarriage aircraft was powered by two three-bladed, 325-hp turbocharged Continental TSIO-520-VB piston engines. Although it was smaller than the EMB-110s that it replaced, its appearance at predominantly light Beechcraft, Cessna, Mooney, and Piper characterized Republic Airport next to its single Passenger Terminal and boarded by ticket holders through its port door located behind the wing, gave it a “mini-airliner” command.

Its pilot was just as “single” in number and its flight attendant count was decidedly lower than that, or zero. Nevertheless, it demonstrated the secondary purpose a general aviation airfield could serve, where parking was complimentary and only feet from the check-in counters, congestion was unheard of, and the quick air shuttle flight, replacing the Verrazano-Narrows and Goethals bridges, facilitated a link to the national air transportation system through connecting PEOPLExpress flights.

When Continental later acquired PEOPLExpress, PBA provided the same feed to its route system through Newark.

Photo Courtesy: Guido Warnecke

While there was no scheduled airline service between ten-mile-separated Republic and Long Island MacArthur airports, I created my own, of sorts, with four-place Cessna C-172 Skyhawks.

As a high-wing, four-seat, general aviation airplane powered by a single 160-hp, dual-bladed Avco Lycoming O-320-H2AD piston engine, it offered flight training-consistent performance: a useful load of 910 pounds, a maximum takeoff weight of 2,300 pounds, a 43-gallon fuel capacity, and a 125-knot speed. Its sea level rate-of-climb was 770 fpm; and its service ceiling was 14,200 feet.

Taking the left seat and accompanied by my instructor in the right, I made several flights between the two Long Island airports, performing outside aircraft inspections, starting the engine with the obligatory “Prop clear” yell, requesting permission to taxi, and completing systems checks in the run-up area, before moving on to the runway’s threshold and receiving takeoff clearance.

Opening the throttles and retaining centerline adherence with minuscule rudder pedal deflections, I gently eased back on the yoke, allowing the high wing to peel the aircraft off the ground in a single leap.

The sky is high and in it man is meant to fly, I often thought.

“Airliner realism” increased during approach to MacArthur, as radio transmissions, such as “USAir 1420, cleared to land, Runway 24,” placed my aircraft in the midst of the “real thing.”

Subsequent departures from the same runway entailed maintaining its heading and a visual flight rules (VFR) parallel of the Long Island Expressway below, until my own, “Republic Tower, this is Cessna 734HD, inbound for landing” transmission granted me continued clearance. A turn to base and final preceded a gentle, three-point touchdown.

Scheduled service it was not, but flying it yourself elevated the experience to something higher.

The dense New York airport network may not have offered the most exotic flying experiences, but their operation by several unique fixed- and rotary-wing carriers more than made up for it.