“The Wings of Man” at Walt Disney World

Written by Shea Oakley

Many visitors to the early days of Orlando’s Walt Disney World in the 1970s and 80s may remember a Tomorrowland ride called “If You Had Wings.” Like many of the attractions of that era, it was sponsored by a major American company, and this was no exception. If You Had Wings was a showcase for Eastern Air Lines, the “Official Airline of Walt Disney World from the park’s opening in 1971 through 1987.

If You Had Wings opened to the public in June 1972 and immediately became one of the most popular rides in the Magic Kingdom. Aside from the merits of the ride itself, its popularity was helped because it was one of the few free rides at the park in an era when visitors had to buy separate ticket books to access many of the park’s other attractions. If You Had Wings also had ice-cold air conditioning, a welcome respite from Central Florida’s often oppressive heat.

Since Disney World buffs rival airline history enthusiasts in terms of fervency and knowledge, there is still a fair amount of information about the ride available online today. Click here for a link to one of several home-movie films of the experience available on YouTube.

As someone who rode the attraction countless times from early boyhood through my teenage years and later became a commercial aviation historian, the connection for me between Eastern and the ride was notable in a number of ways.

Little changed throughout the 15-year existence of If You Had Wings. By the waning days of both the attraction and the airline in the late 1980s, it had become a time capsule of sorts, preserving the spirit of Eastern from the height of that airline’s early-70s “Wings of Man period.” The very name of the attraction reflects the long-used and famous advertising slogan in which Eastern promised a “commitment to a very old ideal. That flight should be as natural and comfortable as man first dreamed it to be. That man should be as home in the sky as he is on land.” Gender-inclusive this statement was not. Then again, when “The Wings of Man” was introduced in 1969, not much was.

A certain soaring and somewhat esoteric element of bird-like flight to colorful destinations was present in the sights and sounds of the entire experience. The stirring theme music used at the time in Eastern’s advertising was heard both in the airport lobby-style entrance as well as at the ride’s end. The attraction also heavily showcased the “The New Wings of the Wings of Man,” the Lockheed L-1011. Eastern was the launch customer for the L-1011, as well as several other historic airliners, and had put the tri-jet into service in April 1972, just two months before the ride opened. The L-1011 was marketed by Eastern as the “Whisperliner,” and its imagery was ubiquitous in If You Had Wings. Mock flight announcements for “Whisperliner Service” played as “passengers” waited in line to board their omnimover pods at the ride’s start.

The pods first passed through a globe with a large display model of the L-1011. Shortly thereafter, riders saw projected graphics of the Whisperliner in profile changing into what appeared to be seagulls. These animated birds reappeared from time to time throughout the eight-minute ride to provide visual continuity. At the ride’s end, much larger and more detailed images of Eastern L-1011’s appeared as the participants were told by a deep, yet reassuring voice, “You do have wings, you can do all these things, you can widen your world (a sub-slogan being used by the airline in 1972.) Eastern…we will be your wings.” The narration throughout was accompanied by a catchy Disney-created song called “If You Had Wings.”

Over the years, few changes were made to the attraction. The L-1011 model was eventually replaced with one of a Boeing 757, another aircraft that Eastern was the launch customer for. Then, in 1987, new owner Frank Lorenzo pulled the plug on Eastern’s “official airline” relationship with Disney, as part of his wholesale gutting of Eastern while he pillaged its assets. However by this point, the “Wings of Man” ad campaign and the optimistic idealism behind it had already been gone for nearly a decade. The slogan was replaced by “We Have to Earn Our Wings Every Day,” in 1978, and then by several other more forgettable ones until the great airline ceased to exist in early 1991.

The ride captured the spirit of a special time in the history of a special company, one I flew often during my formative years as an “avgeek.” That particular era in Eastern’s history has long captured my imagination . In a very physical sense, as long as I could hop on If You Had Wings, it was a spirit I could viscerally experience and re-experience. I miss both the ride and, more importantly, the airline it represented.

Top image by Dada1960 [CC BY-SA 4.0], from Wikimedia Commons.

Originally published on NYCaviation.com

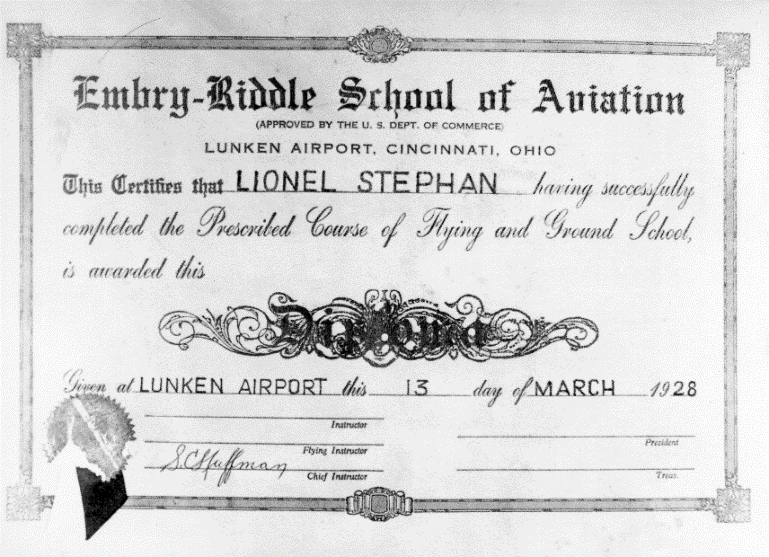

Captain Lionel “Steve” Stephan (left) at a 1985 Embry-Riddle reunion. (

Captain Lionel “Steve” Stephan (left) at a 1985 Embry-Riddle reunion. (