airline postcard,airlines,Asa Candler,ATL,Atlanta,Candler Field,Coca-Cola,Delta Air Lines,Eastern Air Lines,Hastsfield-Jackson,postcard

ATLANTA AIRPORT ON POSTCARDS

By Marvin G. Goldman

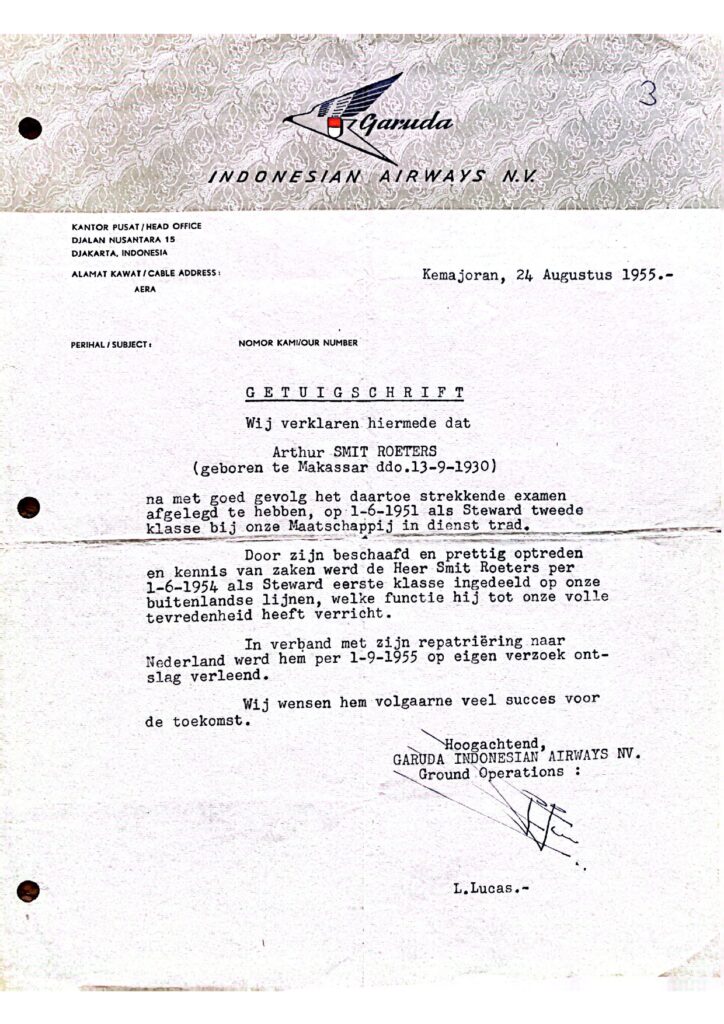

In 1925, the owner of Coca-Cola, Asa Candler, leased to the City of Atlanta his abandoned auto racetrack site for development into an airfield named Candler Field.

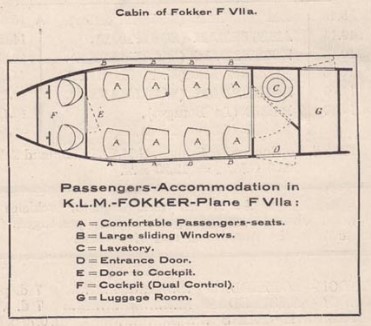

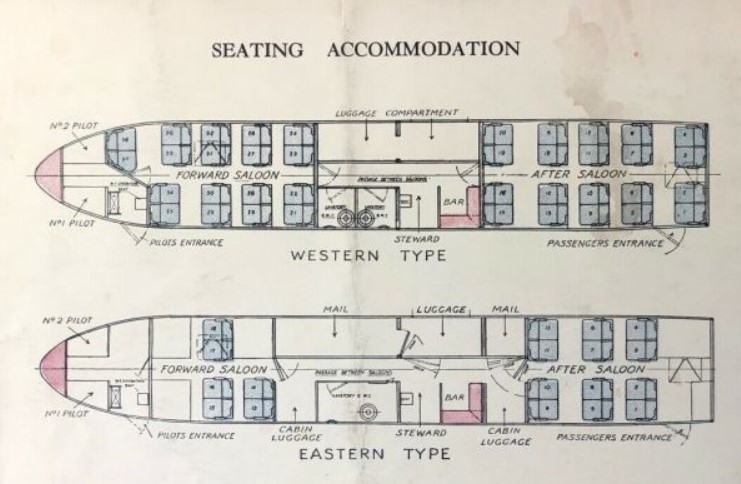

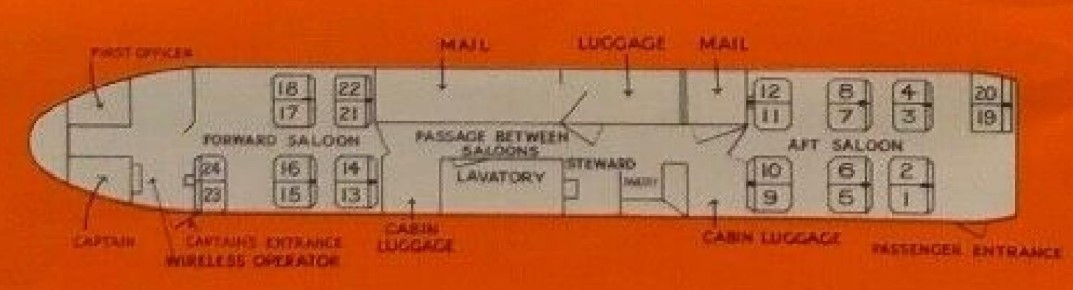

The first airlines to serve Atlanta were Florida Airways which operated from 1926 to 1927; St. Tammany Gulf Coast Airways, 1927, which became a division of Southern Air Transport System in 1929 and in turn part of American Airways in 1930; Pitcairn Aviation which started in 1927, was renamed Eastern Air Transport in 1930 and then became part of Eastern Air Lines in 1934; and Delta Air Service (later named Delta Air Lines) in 1930. During the 1930s, both Delta and Eastern expanded their routes into and out of Candler Field and became the main airlines serving Atlanta at the time.

In 1929, the City of Atlanta purchased the airfield from Asa Candler on favorable terms, and though the airport was officially renamed Atlanta Municipal Airport in 1942, it continued to be popularly referred to as Candler Field.

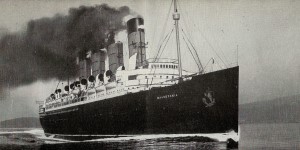

Here is my earliest postcard of Candler Field showing an airline:

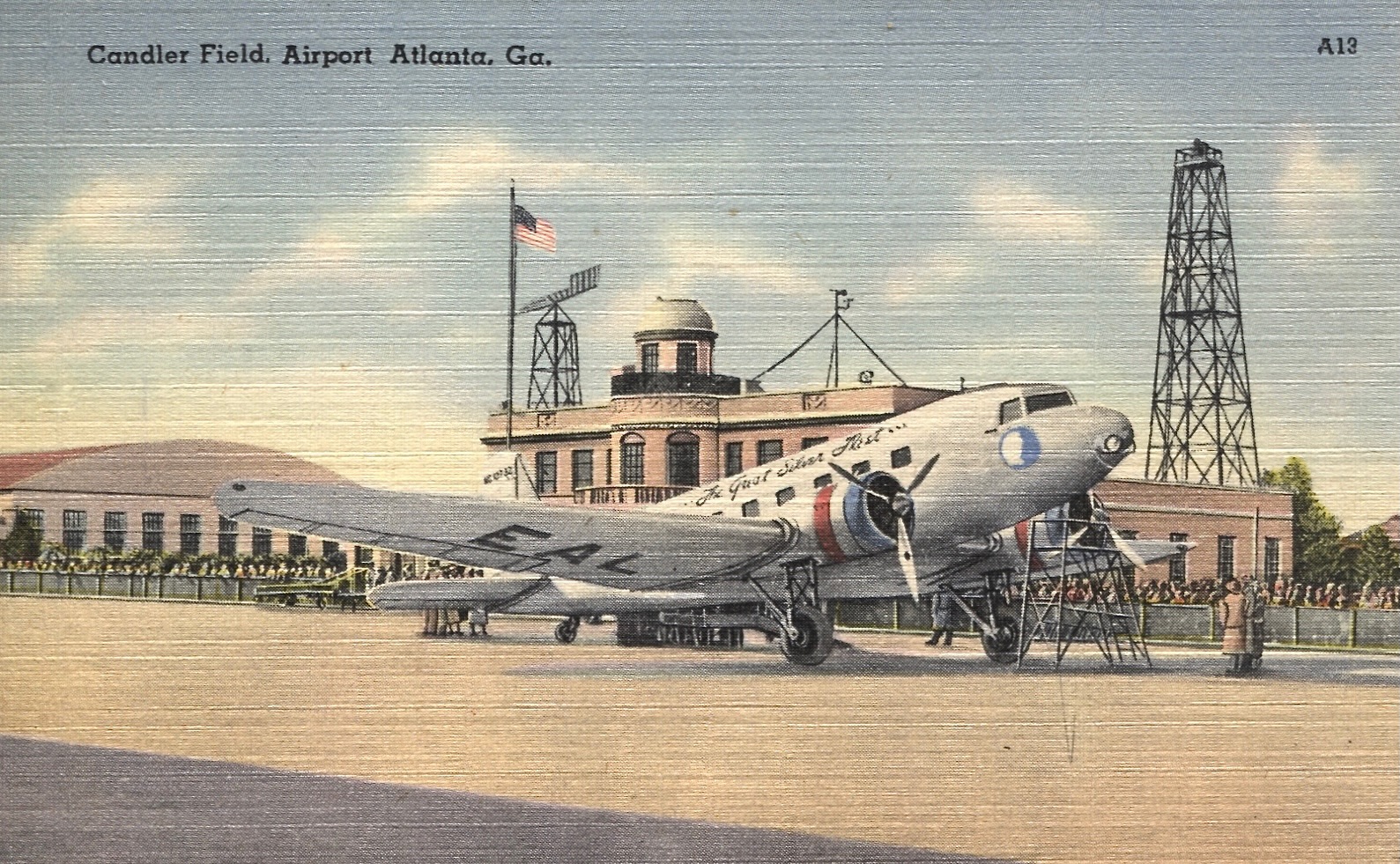

In March 1939, Candler Field built its first control tower in a six-story building with administrative facilities. The control tower can be seen in this next card:

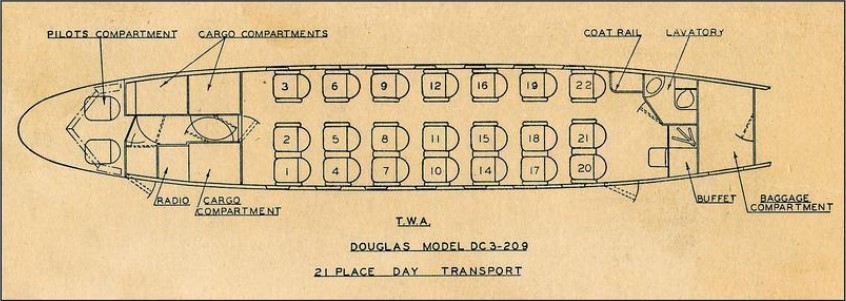

In 1940, Delta Air Lines acquired four DC-2s, but these were retained only until the end of that year, being replaced by DC-3s.

During World War II, Candler Field also became a U.S. air base, and it doubled in size. In 1941, Delta moved its headquarters from Monroe, Louisiana, to Atlanta, and for decades it has been the dominant airline there.

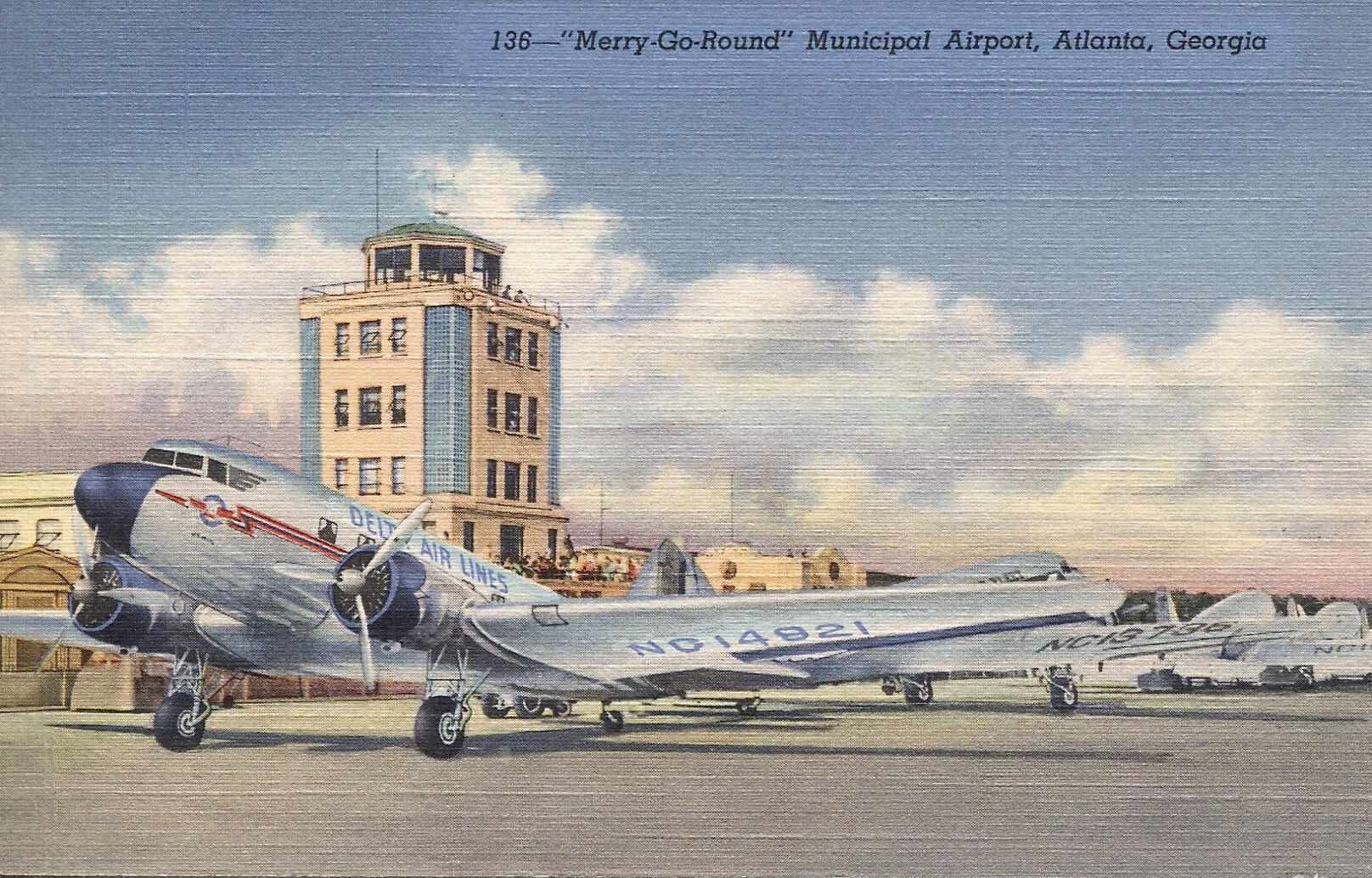

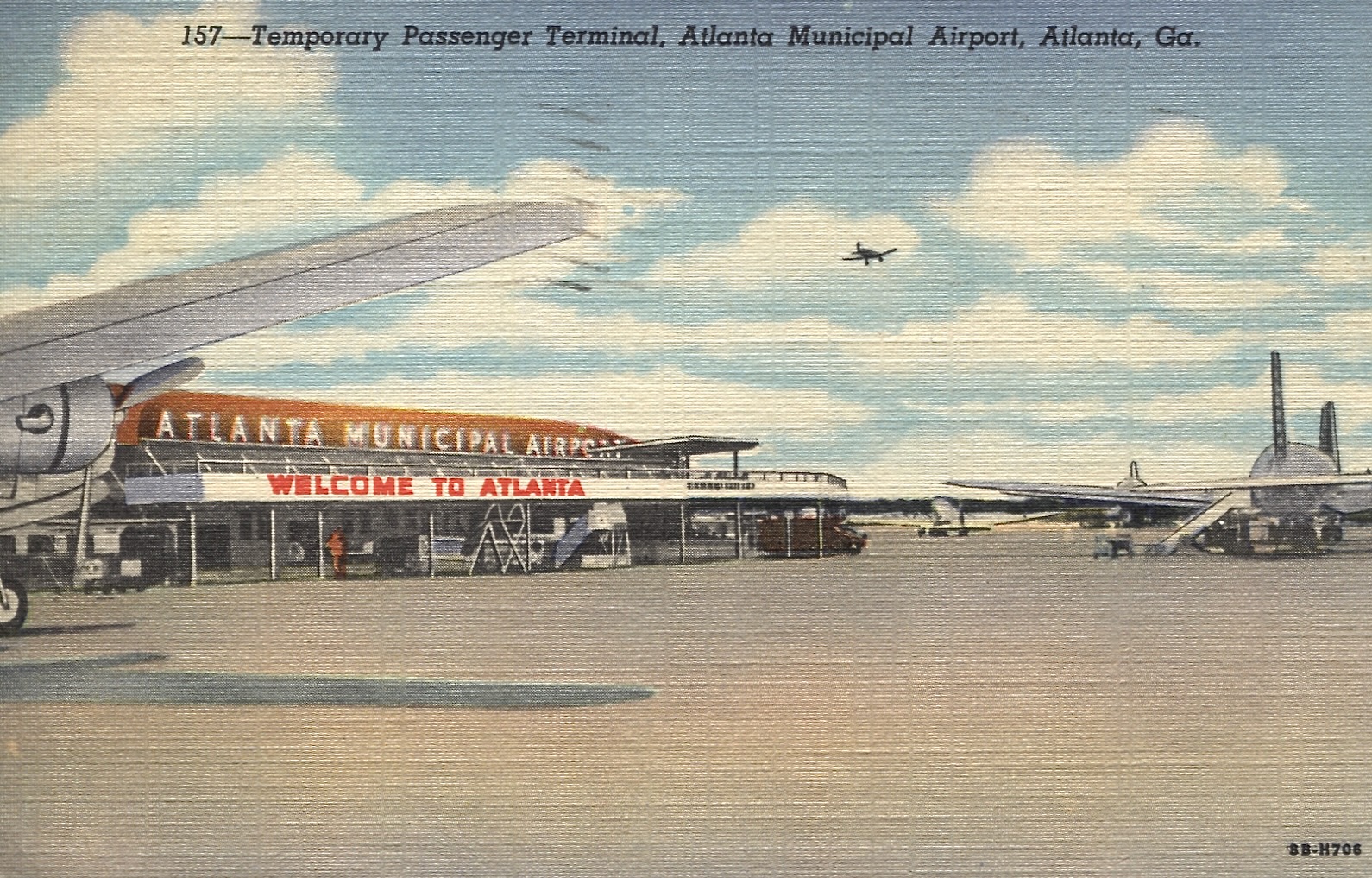

Passenger numbers continued to grow, and in 1948 the airport closed its old terminal building and moved operations into a Quonset hut war-surplus “temporary” terminal while it developed plans to build a larger permanent terminal. That year saw more than 1 million passengers pass through Atlanta airport.

The “temporary” terminal proved to be not so temporary. It served until May 1961, when a new terminal designed to accommodate the jet age finally opened. Here are three postcards from the “temporary” terminal era (1948-1961) at Atlanta Municipal Airport.

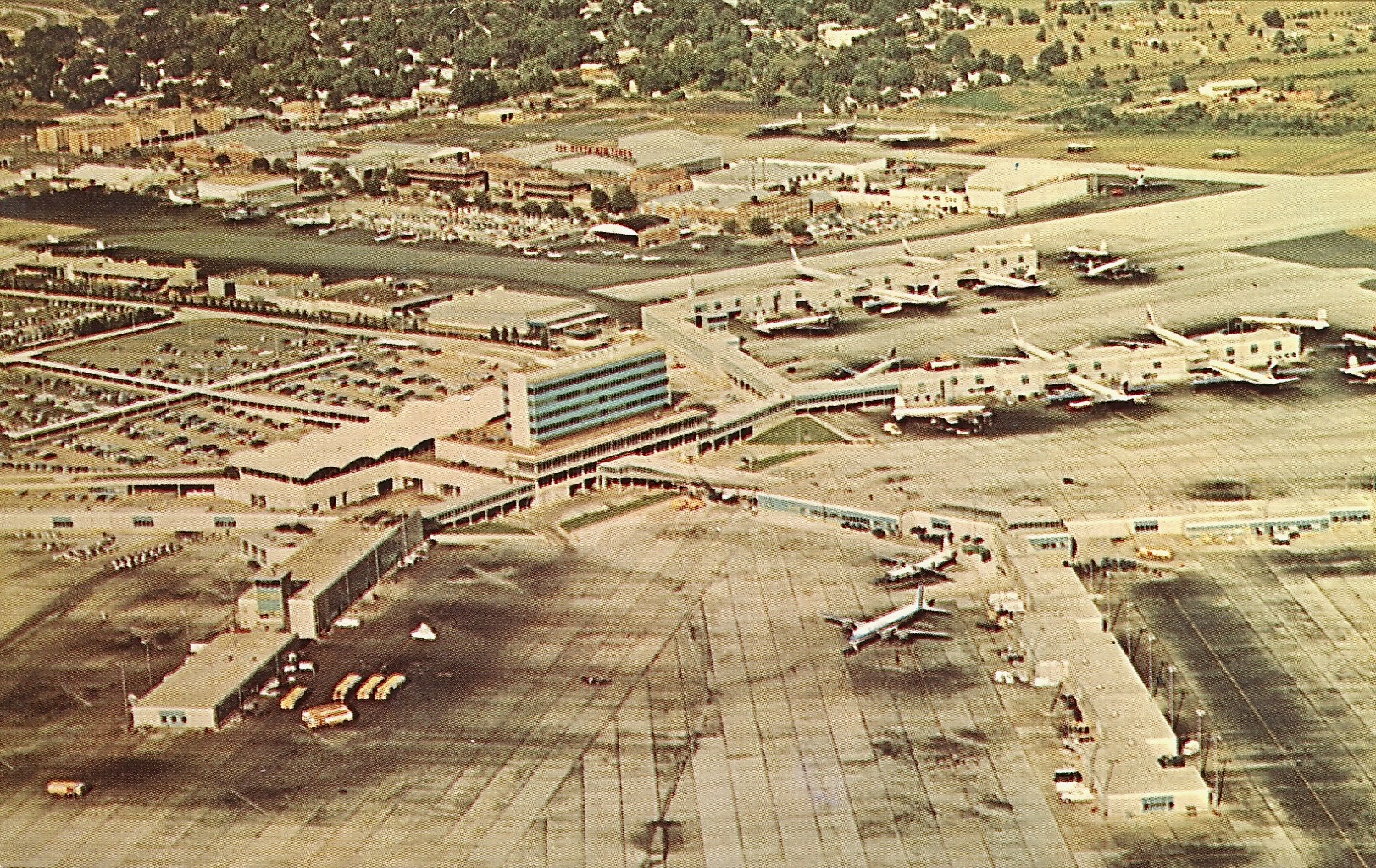

On May 3, 1961, Atlanta Municipal Airport finally opened its new Jet-Age terminal, publicizing it as the largest single terminal in the U.S. The terminal was designed to accommodate 6 million passengers a year, but in its first year, 9.5 million passengers utilized it!

Long-time Mayor William B. Hartsfield, the driving force behind the development of Atlanta Airport as a major airline hub, passed away on February 22, 1971, and on February 28, 1971, the airport name was changed to William B. Hartsfield Atlanta Airport. On July 1, 1971, following the launch by Eastern Air Lines of the airport’s first international service (to Mexico and Montego Bay), the airport was again renamed to William B. Hartsfield Atlanta International Airport.

On September 21, 1980, Hartsfield Atlanta International Airport opened the Midfield Terminal. It was the world’s largest air passenger terminal complex at the time, designed to accommodate up to 55 million passengers each year. It replaced in stages the old terminal and its concourses A through F.

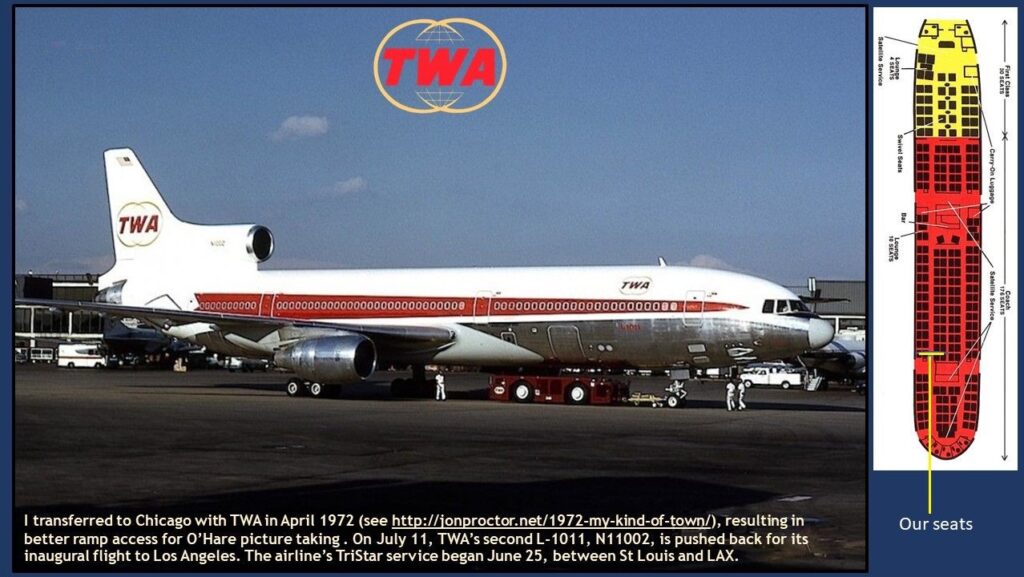

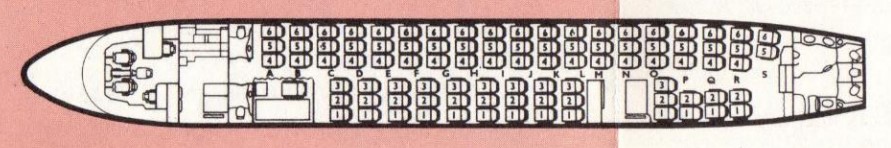

Boeing 727s, Lockheed L-1011s and Douglas

DC-8-61s and DC-9s, taking on passengers at

just one of Delta’s concourses at Hartsfield

Atlanta International. Pub’r Thomas Warren,

Atlanta, nos. 561109 and A-153.

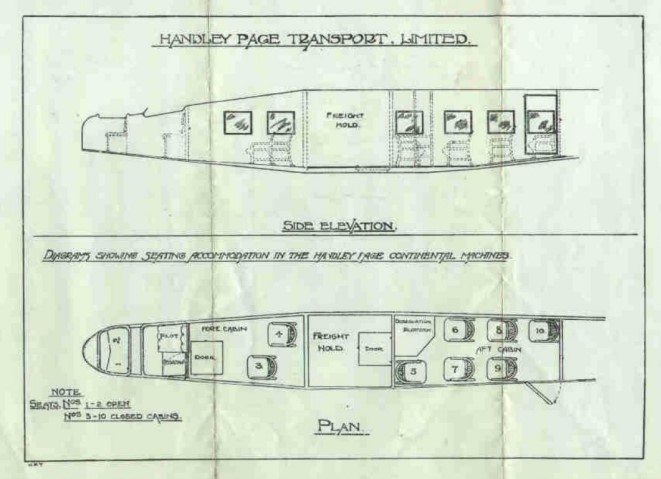

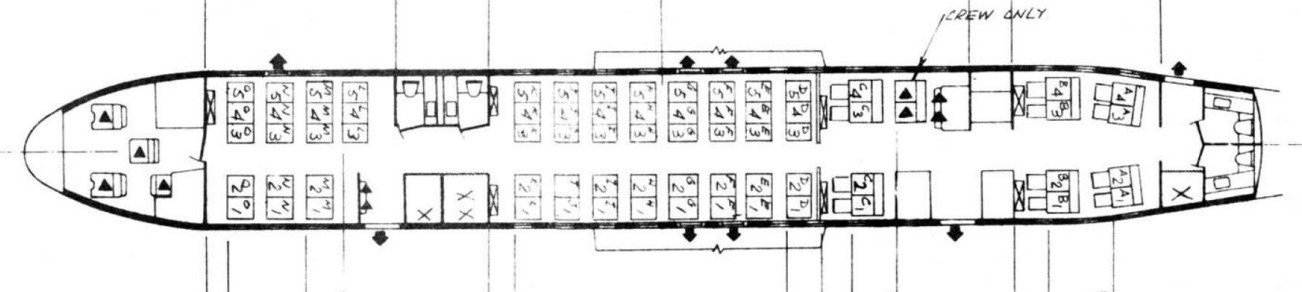

in the 1990s, showing the seven concourses of

the Midfield Terminal, T and F for international

flights and A through E primarily for domestic

flights. Pub’r APS, Kennesaw, Georgia, nos.

K41231 and KA-3-4856.

In October 2003, to honor former Atlanta Mayor Maynard Jackson, the Airport was again renamed, this time as Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport.

Since 1998, Atlanta Airport has been the world’s busiest passenger airport. It serves on average 2,700 departures and arrivals daily by airlines operating nonstop to more than 150 U.S. destinations and over 70 international cities in 50 countries. In 2024, Atlanta airport handled 108.1 million passengers (an average of about 295,000 a day), the second-highest year in its history. This represents nearly a full recovery from the general decline in passenger traffic due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which began in 2020 and followed the airport’s record 110 million passengers in 2019.

Delta is by far the dominant airline in Atlanta, with about 73% of the passenger traffic. Southwest is second with 8%, followed by Spirit, Frontier, Endeavor Air (operating as Delta Connection), American and United.

Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport is now engaged in a major 20-year capital improvement program, which includes modernizing its domestic terminal, expanding concourses and cargo operations, replacing parking facilities, and eventually developing a hotel and mixed-use facilities.

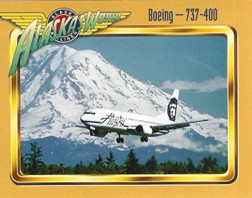

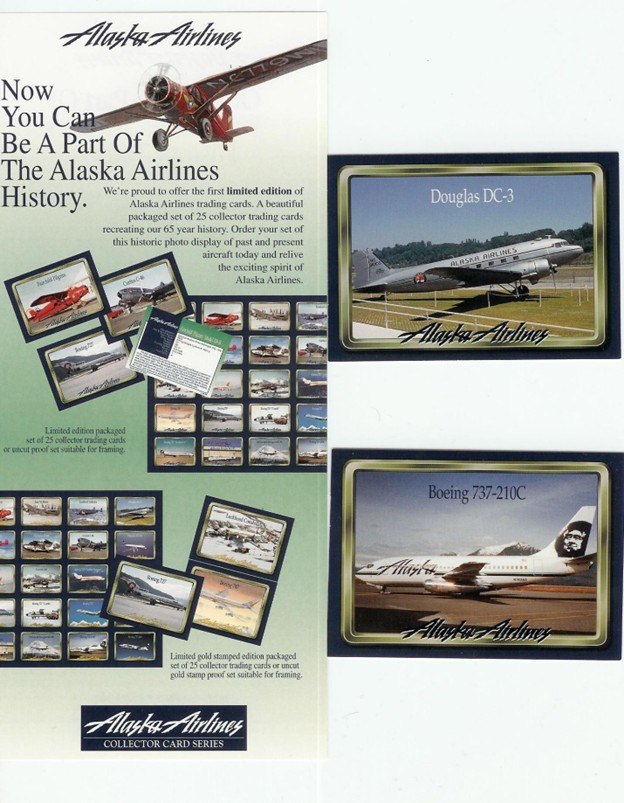

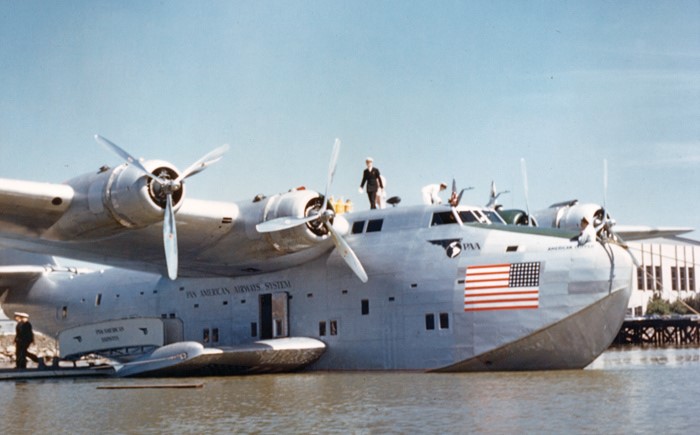

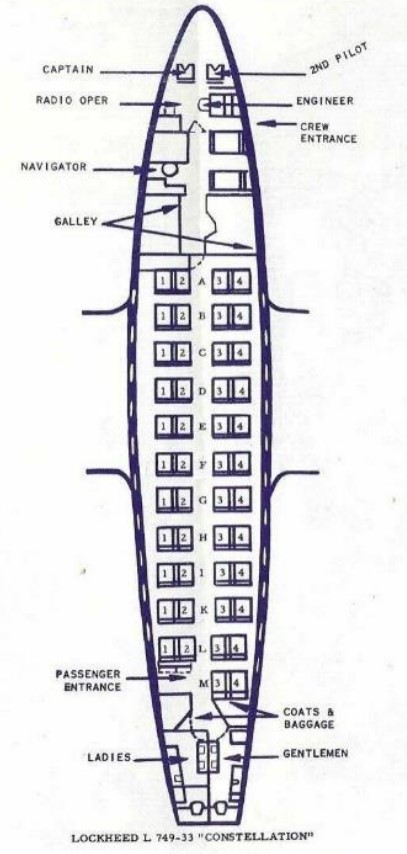

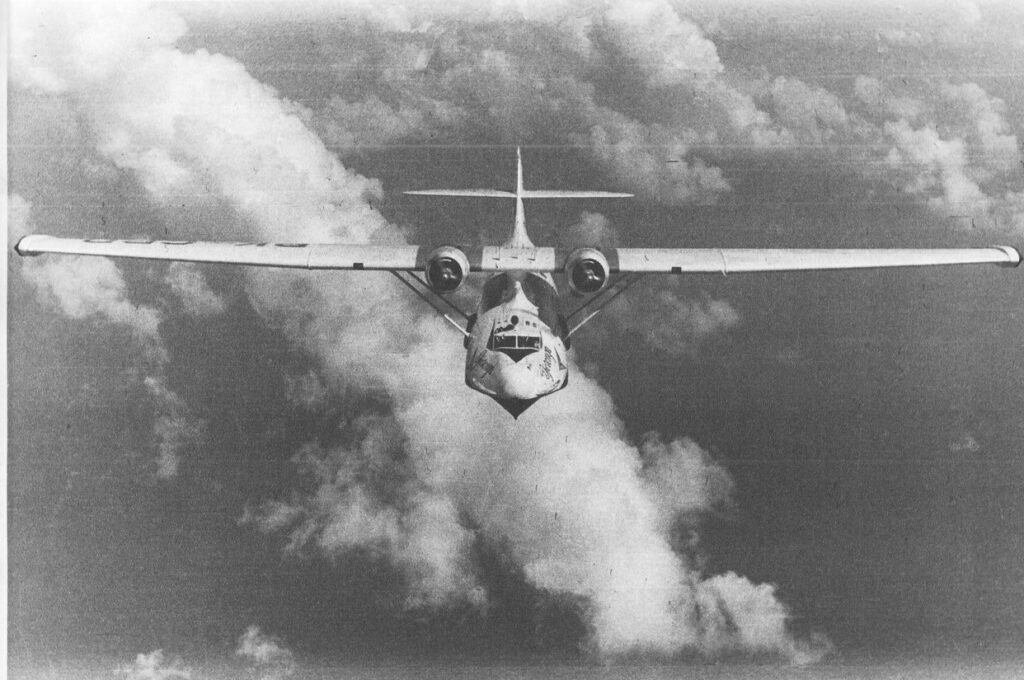

We close this Atlanta postcard article with a beautiful card showing the very aircraft that now resides in full splendor at the Delta Flight Museum, the site of Airliners International 2025 ATL, June 25-28, 2025, adjacent to Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport.

Notes: The originals of all postcards shown are in color and from the author’s collection. All are in standard or continental size. I estimate their rarity as Uncommon: The Candler Field card with an Eastern DC-2; the ‘Temporary’ terminal card with a Delta DC-3 in the center; the Piedmont Airlines card; and the card showing Delta aircraft at the rotundas and gates added in 1968. The rest of the postcards are fairly common. This article is an update and revision of an earlier one by the author on Atlanta airport postcards published in the Spring 2015 issue of The Captain’s Log, vol. 39, no. 4.

Airliners International 2025 ATL Postcard Exhibits by Collectors: The AI 2025 show at the Delta Flight Museum, Atlanta airport, will again feature a display of airline and airport postcard exhibits. Whether you’re an experienced collector or a beginner, please consider submitting an exhibit. It’s a lot of fun, and the postcard displays stimulate greater interest in collecting airline and airport postcards. This year’s Postcard Exhibit Guidelines can be found at airlinersinternational.org under the tab Contest Information (even though it’s an exhibit, not a contest). I look forward to seeing you at Airliners International 2025, Atlanta, June 25-28.

References:

www.sunshineskies.com/atlanta.html. This is a great website with hundreds of pictures, many postcard views, and extensive information on the history of Atlanta airport.

www.atl.com. Official site of Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport

www.deltamuseum.org. Official site of The Delta Flight Museum, Atlanta airport, where Airliners International 2025 will be held June 25-28, 2025.

golldiecat.tripod.com/atl.html. History of Hartsfield Atlanta International Airport from 1961 to 1980, illustrated with postcard views.

Cearley, Jr., George W., Atlanta (1991) and The Delta Family History (1985), each self-published.

Davies, R.E.G., Delta: An Airline and Its Aircraft. Paladwr Press (1990).

www.wahsonline.com. Official site of the World Airline Historical Society.

Until next time, Happy Collecting. Marvin.