Pan American,PAWA,varig

The History of Safety Cards, Part 3: The Jets Arrive (Turn of the decade 1950s/1960s)

By Fons Schaefers

Early attempts

One of aviation history’s most narrated events of failure is the false start of air transport by jets. I am referring to the years 1952 to 1954 and the operation of the first iteration of the British-built De Havilland Comet. Safety card-wise, this was a non-event as no leaflets specific to the type were carried. BOAC, at the time, used a generic leaflet focusing on surviving a ditching without identifying aircraft types. The other users of the first Comets were Air France, UAT, and Canadian Pacific which, as far as I know, neither used safety leaflets that showed the aircraft type.

Neither meant the introduction of the Tupolev 104 in the Soviet Union in 1956 jet-specific safety cards. Aeroflot was then far away from using safety leaflets at all. CSA, the Czech flag carrier and the only non-Soviet user of the type, did have Tupolev 104-specific safety leaflets but I doubt that was from the start (see 18 July 2017 contribution by Brian Barron under the ‘safety cards’ tile on this website for the CSA Tupolev 104 card and other cards relevant to this part).

Proper start

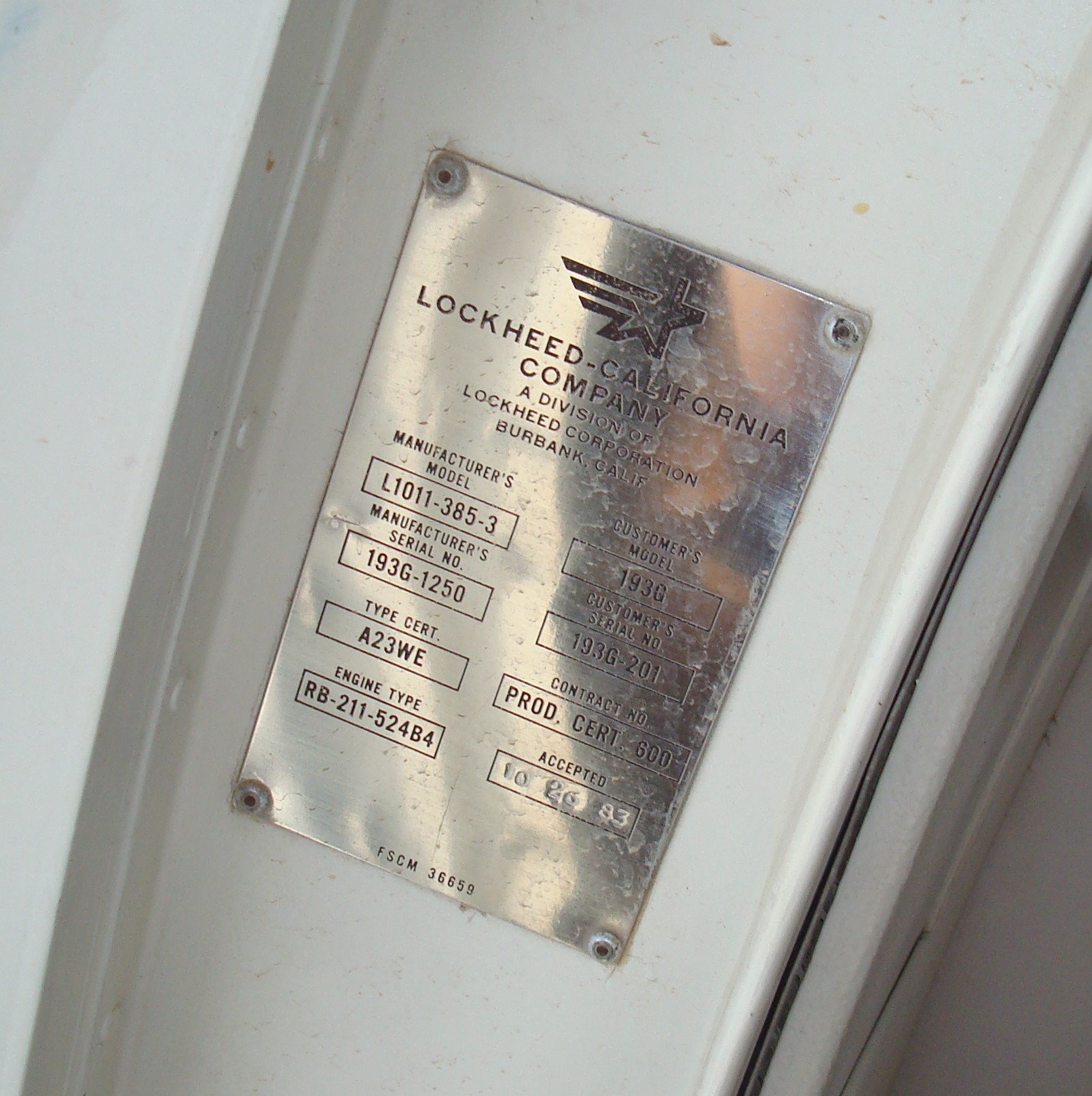

In the western world, jet airliners properly began in 1958. In Britain, De Havilland, now better understanding the phenomenon of metal fatigue, launched the Comet 4, which was put in service by BOAC in October 1958. The French Sud-Est Caravelle took off with Air France and SAS in May 1959. In the USA, the Boeing 707 was introduced by Pan American in October 1958 and by American Airlines and TWA in early 1959, while United and Delta started with the Douglas DC-8 in September 1959. The third US airframe contender was Convair with its 880 model (followed later by the 990 derivative), which started commercial service with Delta in 1960.

The arrival of jet airliners was generally welcomed as a major improvement in air travel. Some even considered it a quantum leap. The new propulsion method meant much shorter traveling times. This was entirely due to their higher speed, as their range was not better: the number of hops on the longest route at the time (the Kangaroo route from London to Sydney) remained about the same: typically eight. The jets also brought a capacity step. Pre-jet aircraft had maximum seating capacities of up to about 100; the first jets jumped to around 180, although initially, airlines employed luxury rather than high-density seating arrangements so typically installed around 110 to 140 seats.

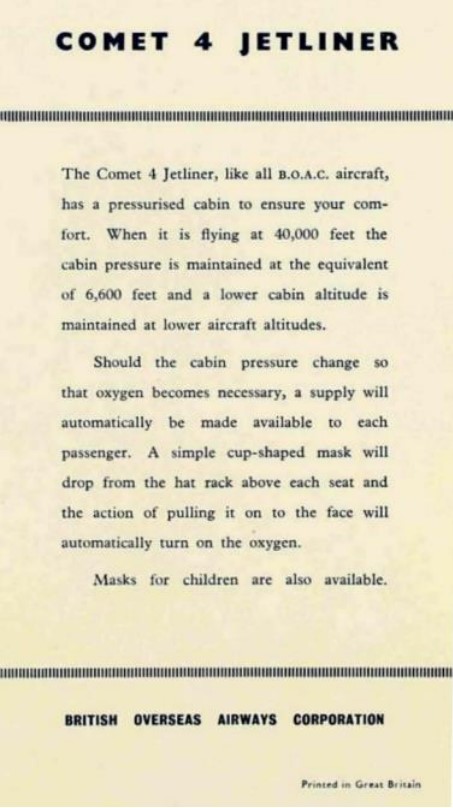

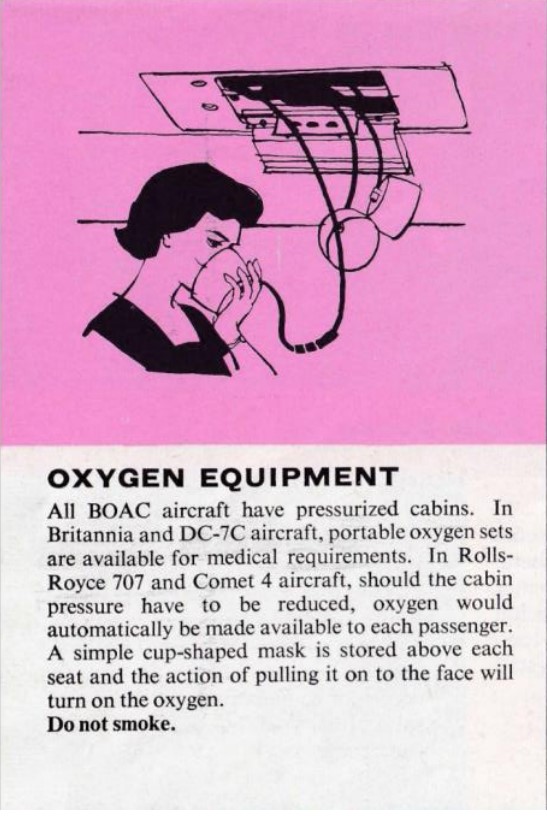

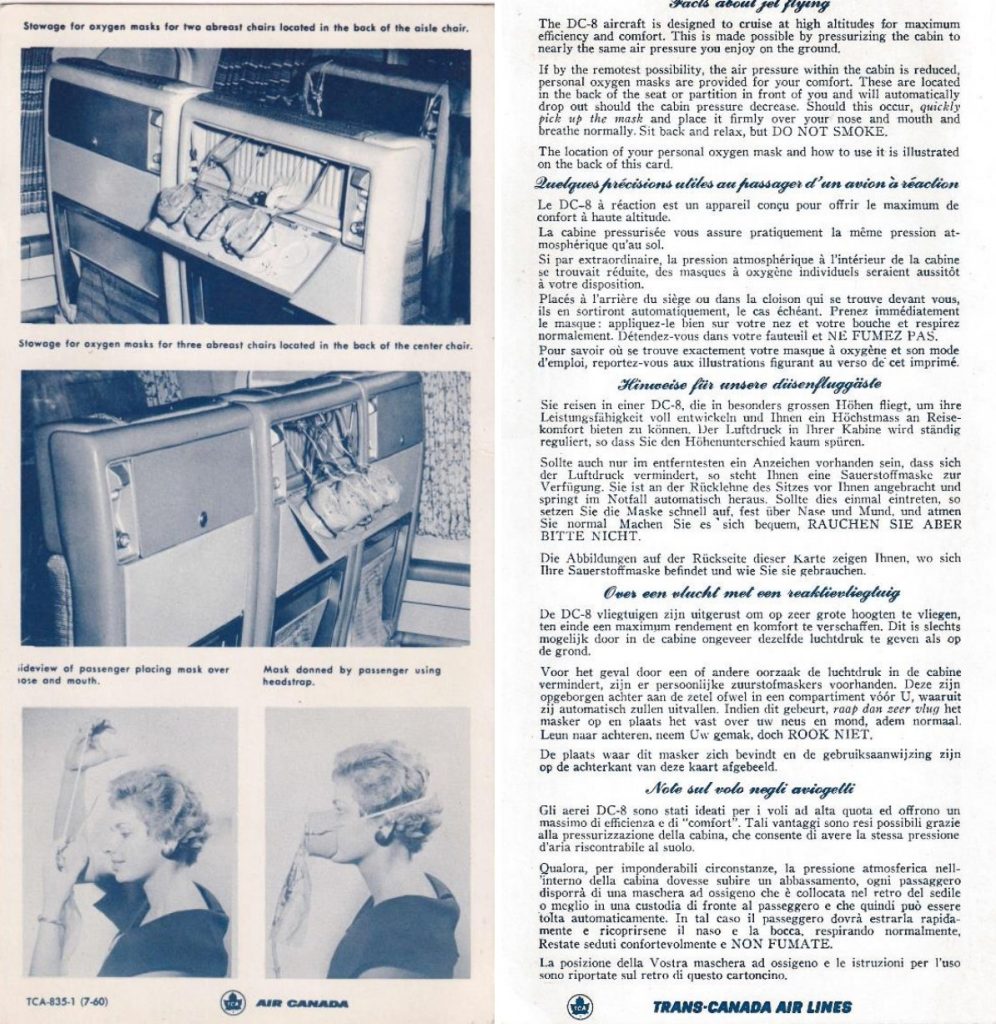

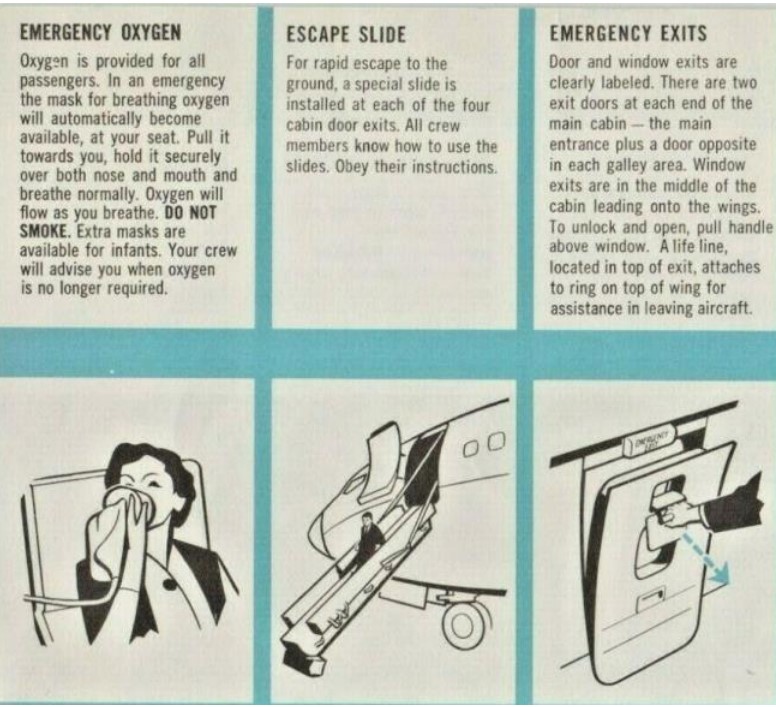

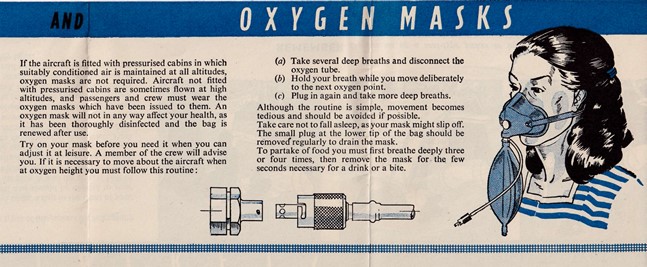

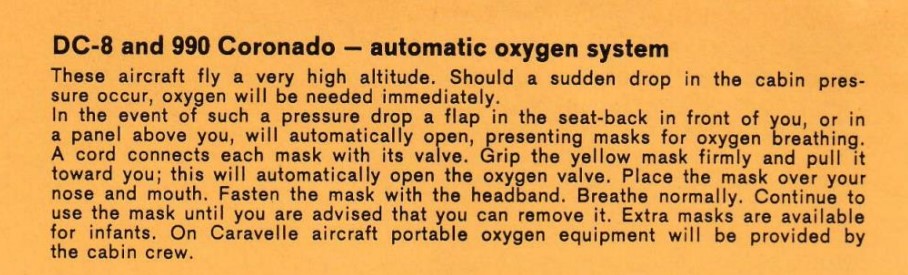

Jet engines vibrate less than piston engines and are most economic at altitudes higher than where the props fly, where ‘weather’ and associated turbulence can be avoided. This brings a smoother and more comfortable ride. Yet, as air at altitude is thinner, it requires back-up oxygen for all occupants in case of a decompression. Here, there was a difference in policy between the two sides of the Atlantic Ocean. In the US, automatic oxygen presentation capability to all passengers was required when flying above 30,000 ft. In Europe, that altitude was 35,000 ft. This meant that aircraft such as the Caravelle and most Comets did not need automatic oxygen as they stayed below 35,000 ft. Exemptions were the long-range Comet 4 which BOAC operated at higher altitudes and the Caravelle when operated under US rules, such as by United Airlines.

Jet’s effect on safety cards

Did the introduction of the jet mean a quantum leap in safety cards? The answer is both no and yes.

No: piecemeal changes

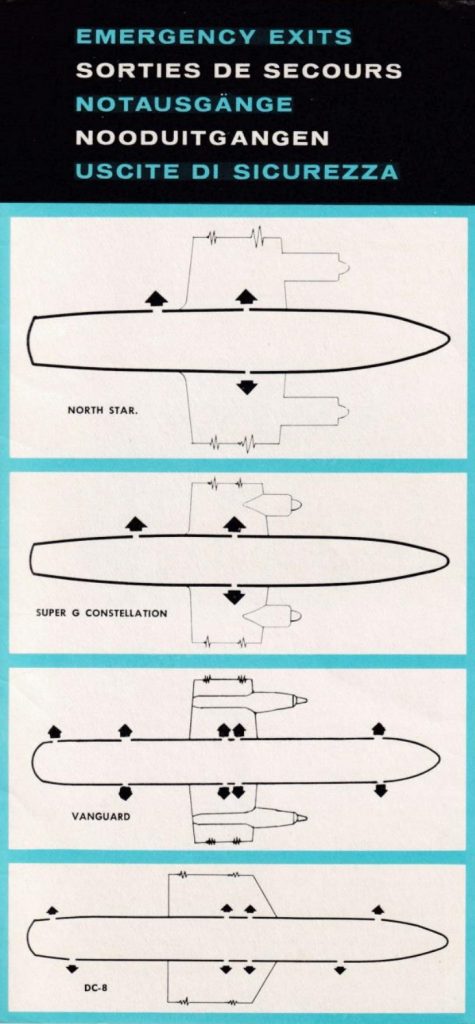

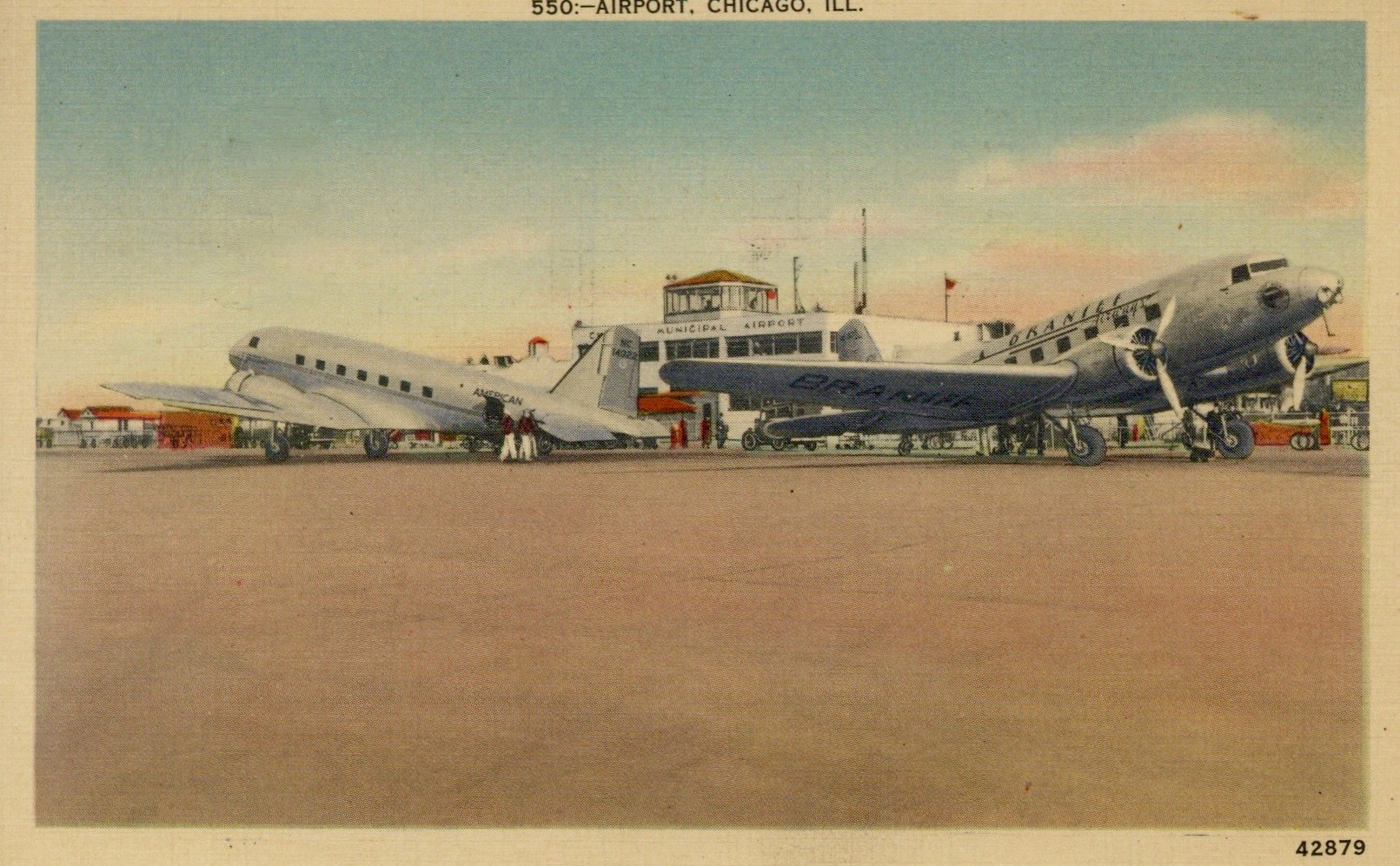

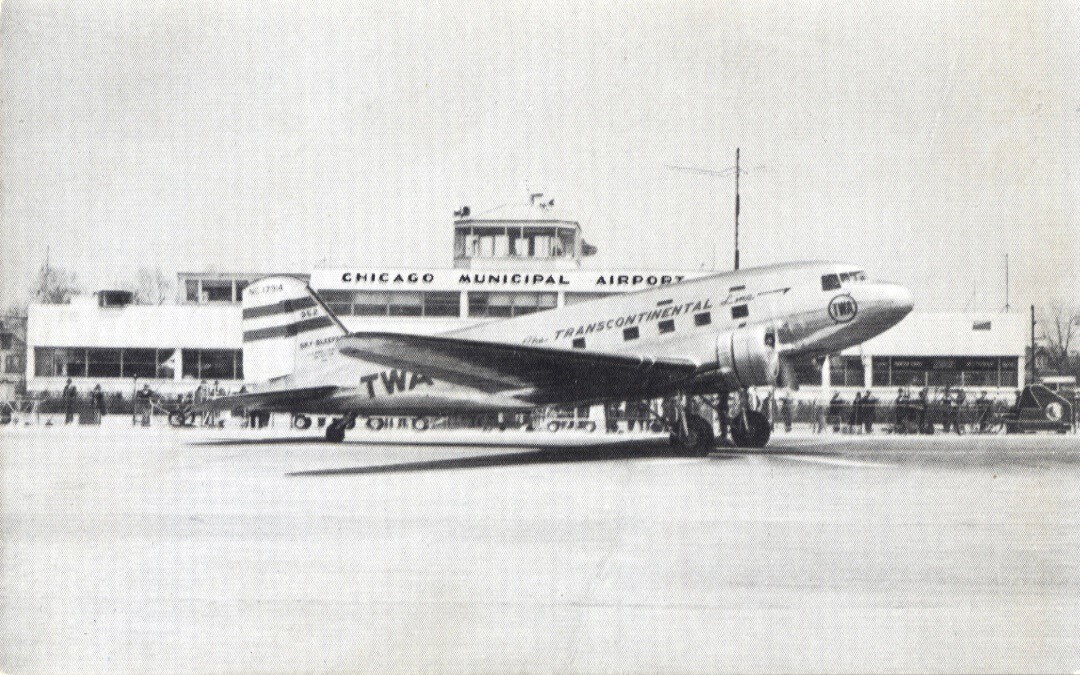

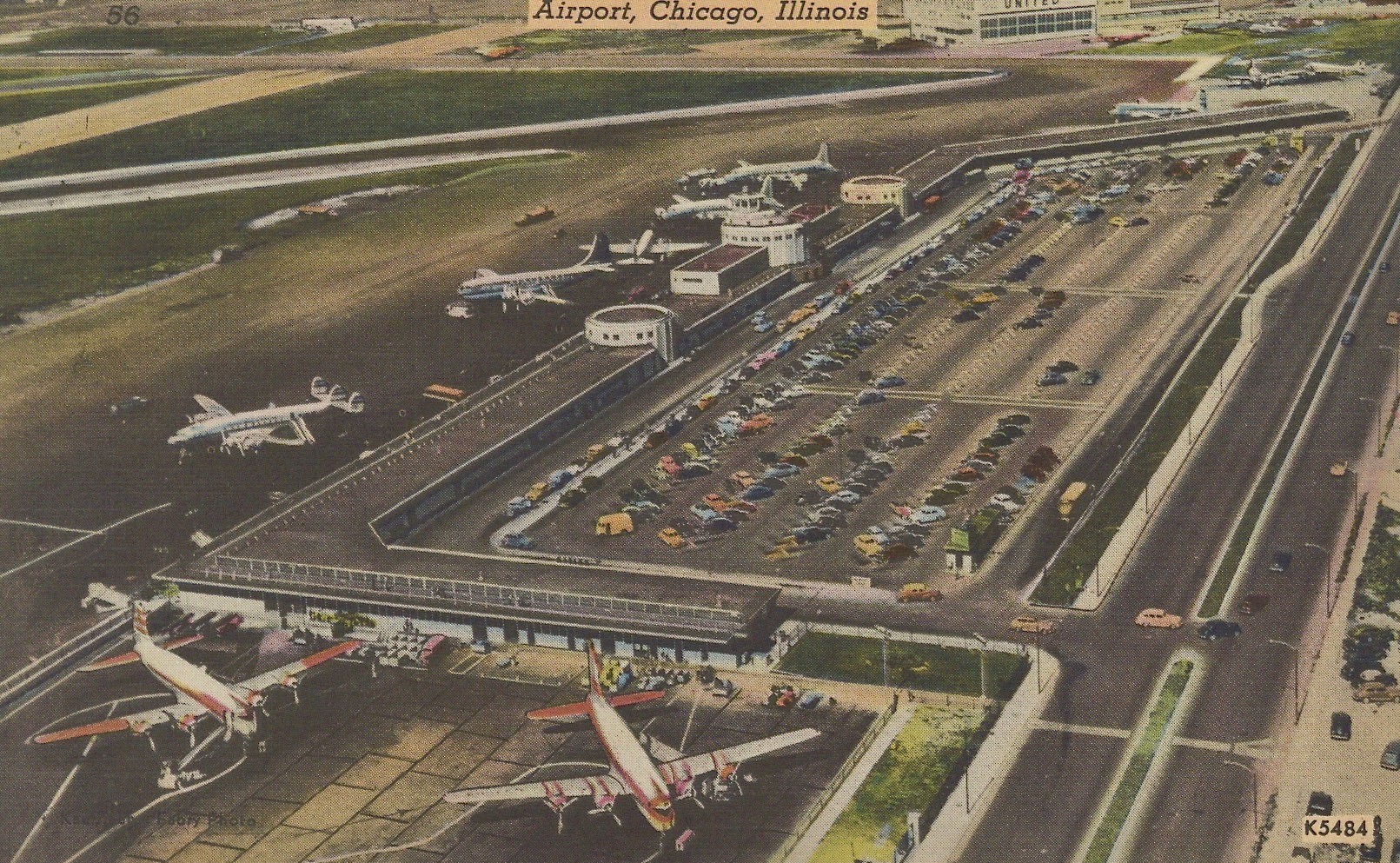

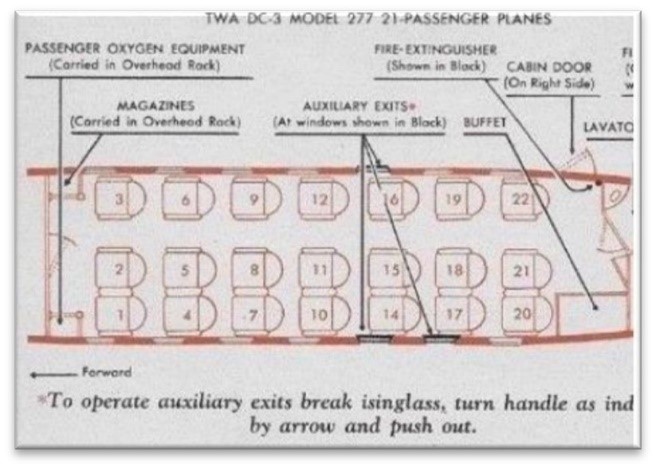

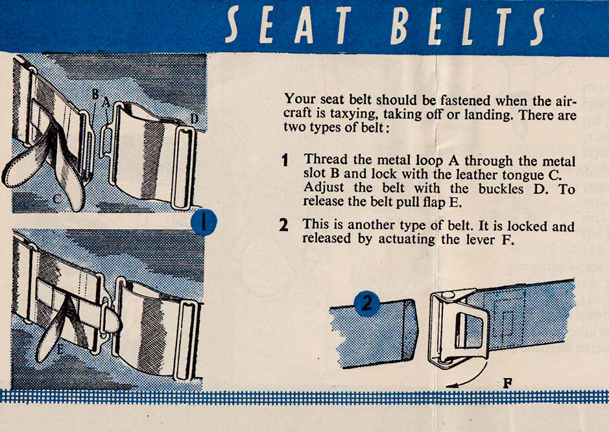

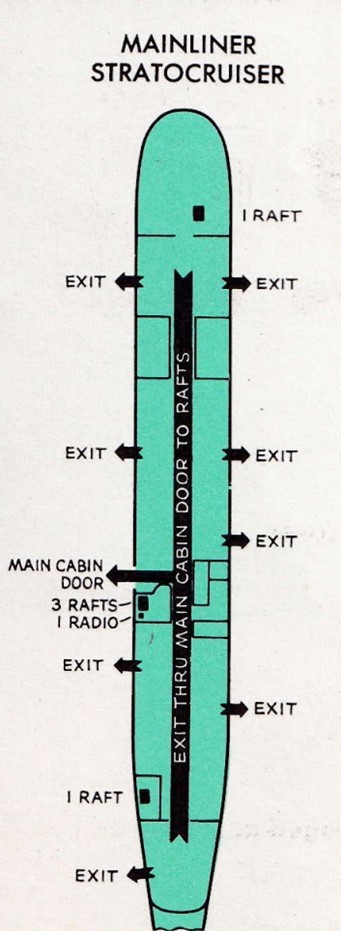

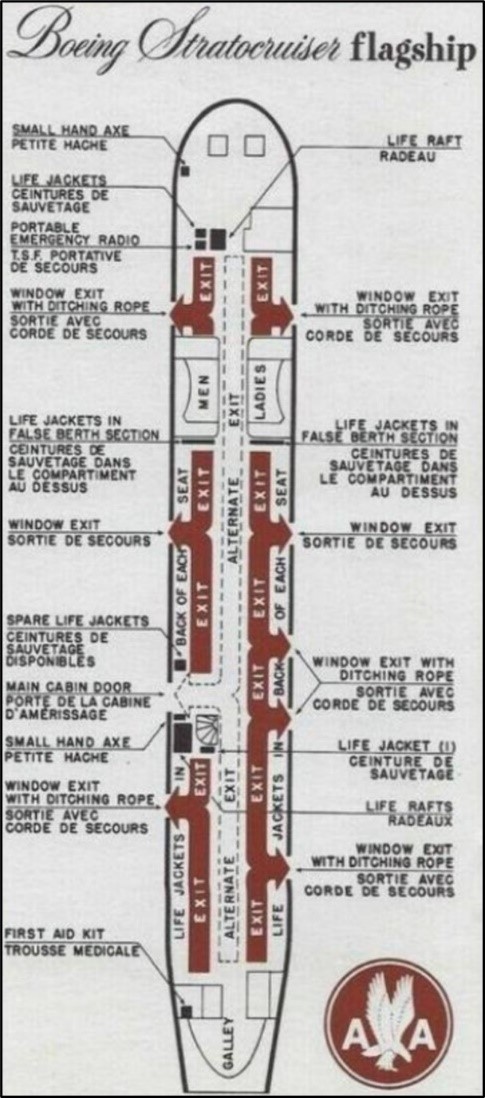

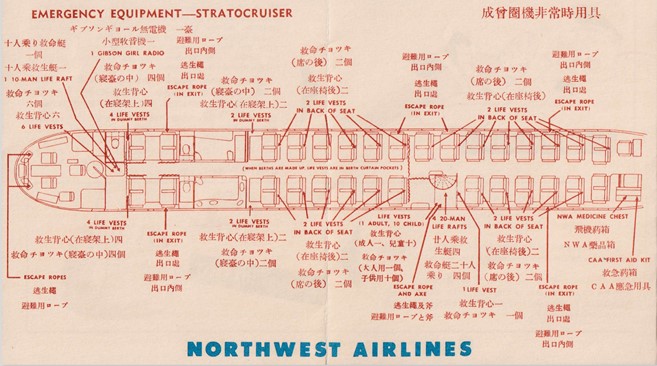

Most of the first airlines to fly jets were flag airlines. Many already had safety leaflets in use for their propliners covering their entire fleets (hence called fleet leaflets). The new jets were simply added to the existing leaflet designs with minimum changes. Good examples of this were BOAC, SAS, TCA and Pan American.

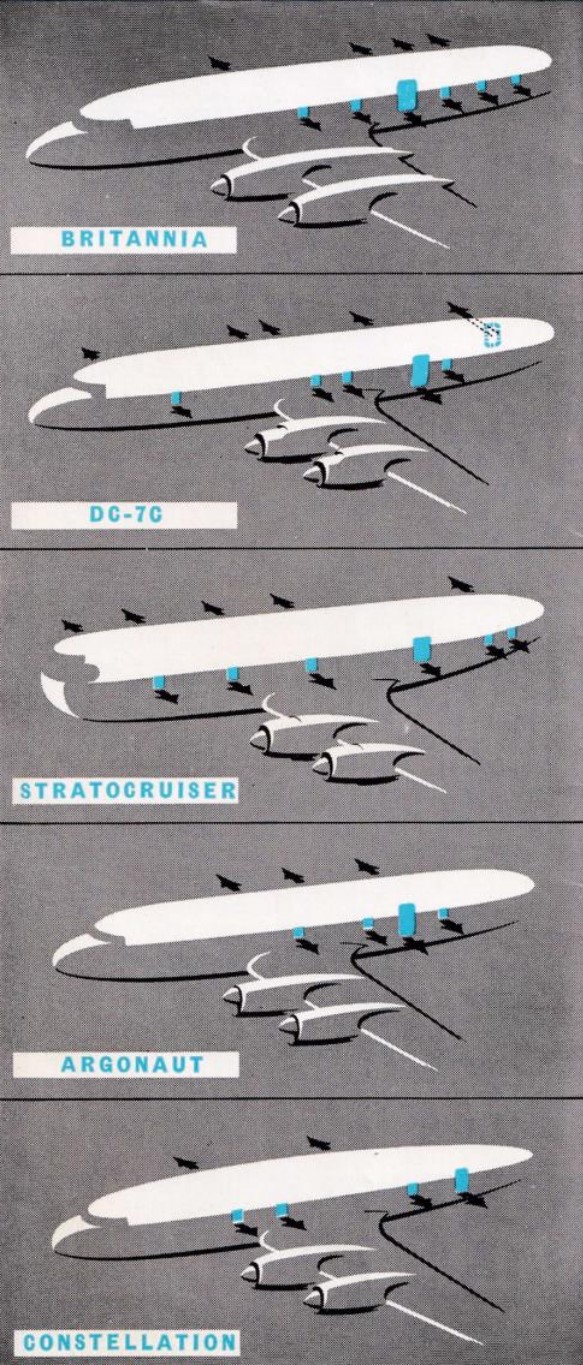

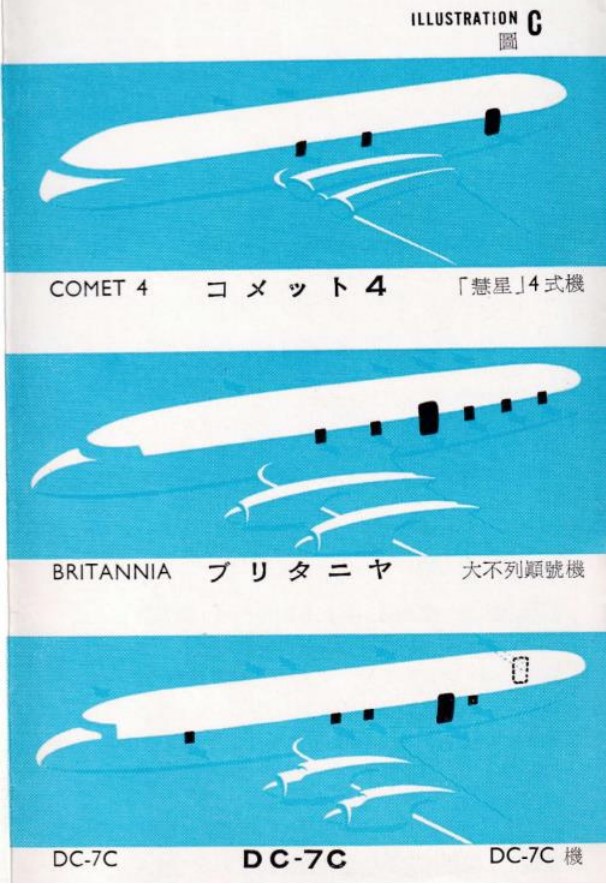

Comparing BOAC’s 1957 elaborative, ditching-oriented safety leaflet edition with that of 1958 shows only one change: the aircraft exit diagrams of three types (Stratocruiser, Argonaut, and Constellation) are replaced by that of the Comet 4 (the Britannia and DC-7C remained).

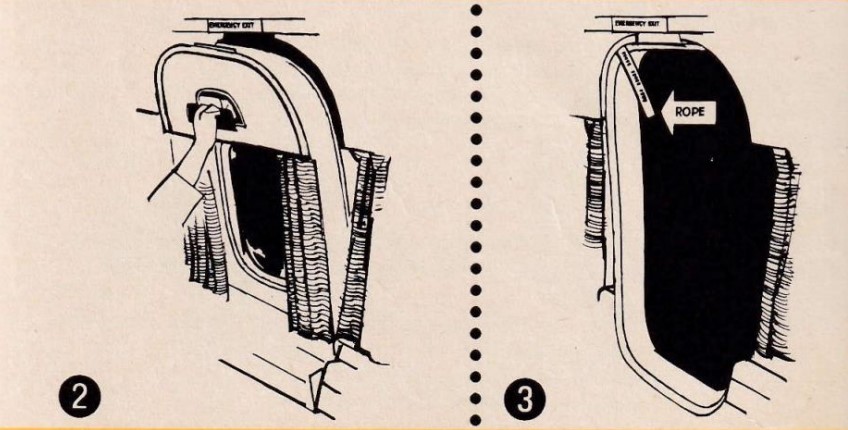

As BOAC flew their Comet 4 up to 40,000 ft it had oxygen provisions for all passengers, so a separate text only leaflet was made to explain those. Its use was no longer required when in 1960 the main leaflet was updated when the Boeing 707 was added to the fleet, and thus to the leaflet. A text plus an illustration on the oxygen equipment was added and, in true piecemeal change style, an illustration of how to open a window exit was added.

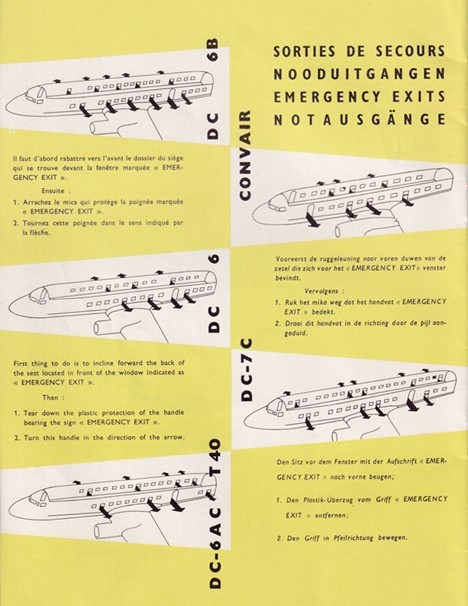

At SAS, we see something similar: in the 1959 edition of the leaflet, the Caravelle is added to the diagram page without any further changes to the leaflet. Even the front page still sports the DC-6B!

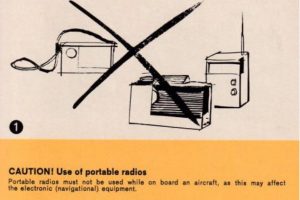

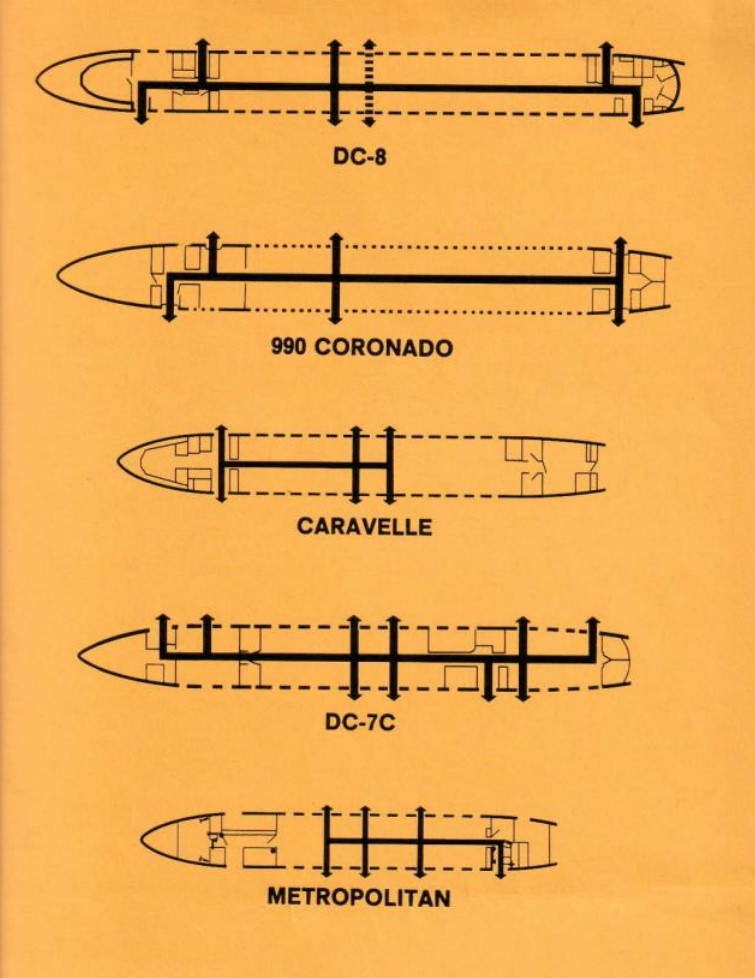

But in the 1962 edition, which has both the DC-8 and Convair990 Coronado added, window exit pictures appear and, for these two types only, so not for the Caravelle as it had none, a page explaining the automatic oxygen system. (See Brian Barron’s contribution for the interim edition, which has the DC-8 added but not yet the 990). In 1962, SAS adds a caution against the use of portable radios on board, as they may affect navigation equipment.

TCA’s 1960 edition of its safety booklet (coded TCA-853) only adds a diagram of the DC-8 but without any exit operation or oxygen guidance. The latter, however, came in the form of a separate card (coded TCA 853-1), with both Trans-Canada Air Lines and Air Canada titles.

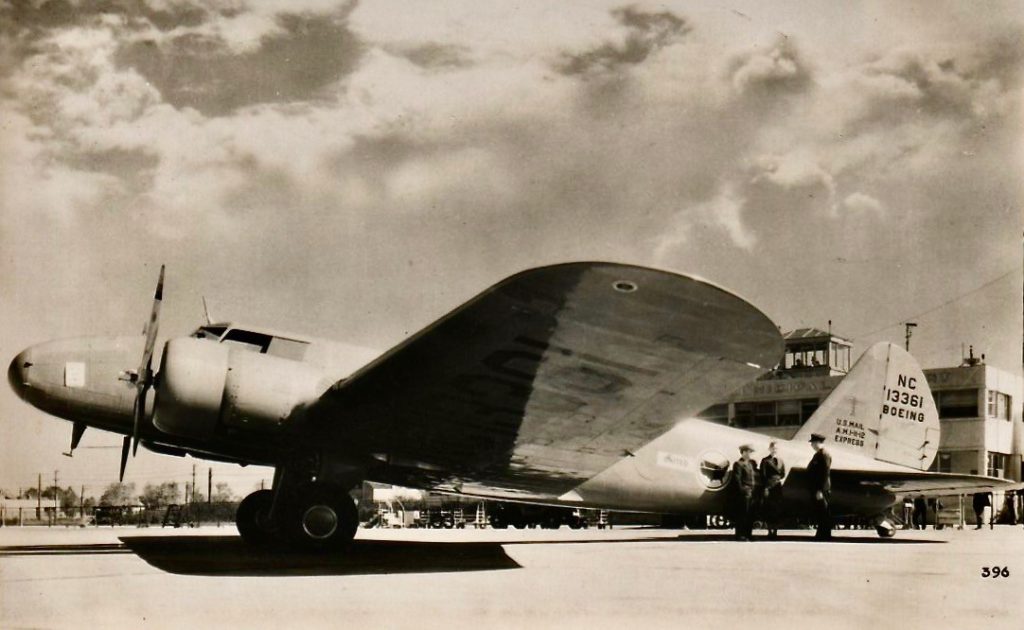

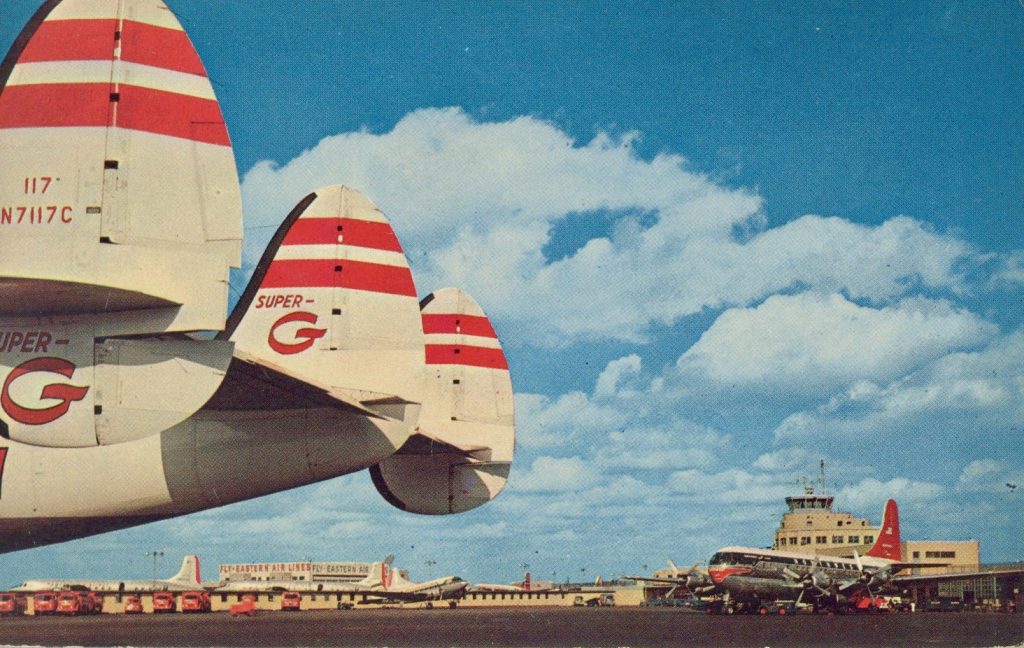

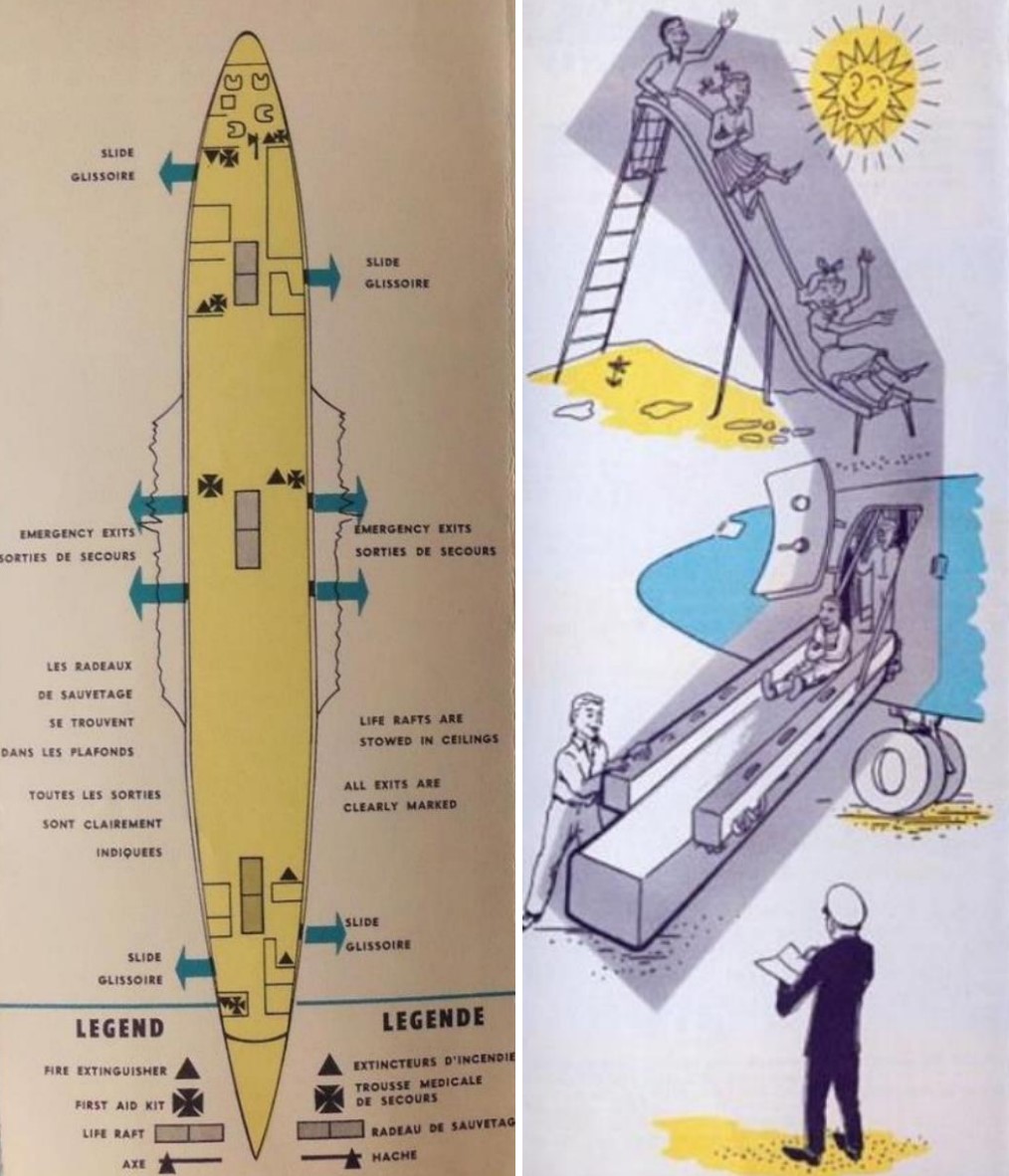

The early Pan American World Airways (PAWA) Boeing 707 folder sees automatic oxygen added to the traditional life jacket and life raft instructions (not shown) bu is otherwise very similar to the previous folder for the DC-7C. The latter’s handheld chute is replaced by an inflated slide and the window exit now depicts that of the Boeing.

In 1961, PAWA added a note about the dangers of using portable radios and other electronic devices as they may cause interference. Although labeled as important, this note was not translated into any of the other seven languages the folder had. So, perhaps it was added last minute.

Yes: new concepts

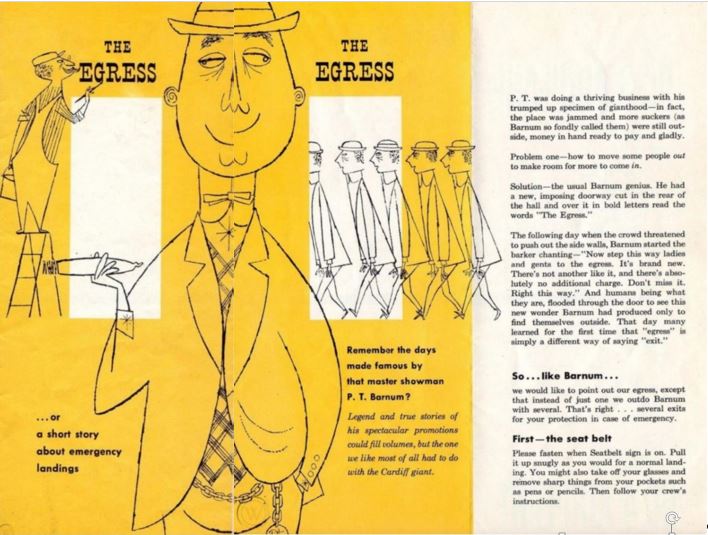

Maybe calling them a quantum leap in safety card development goes too far, but several US airlines did use the new jets as an incentive for launching new concepts and ideas.

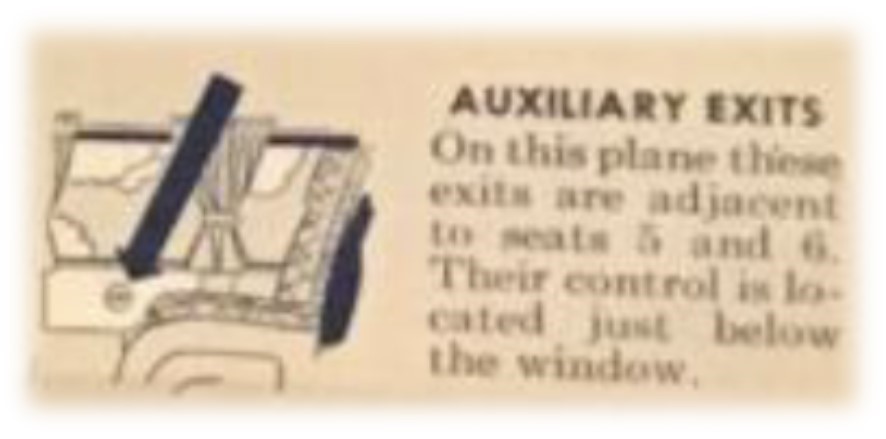

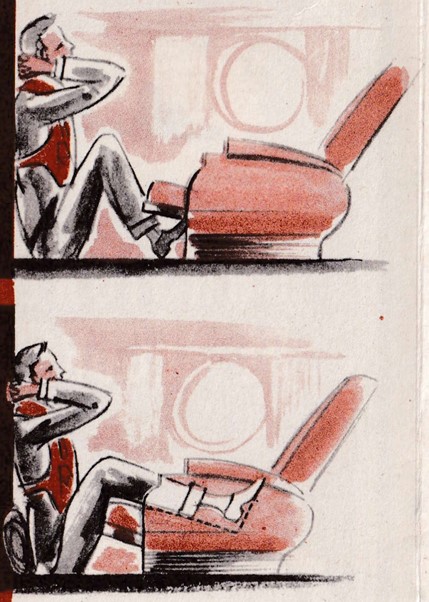

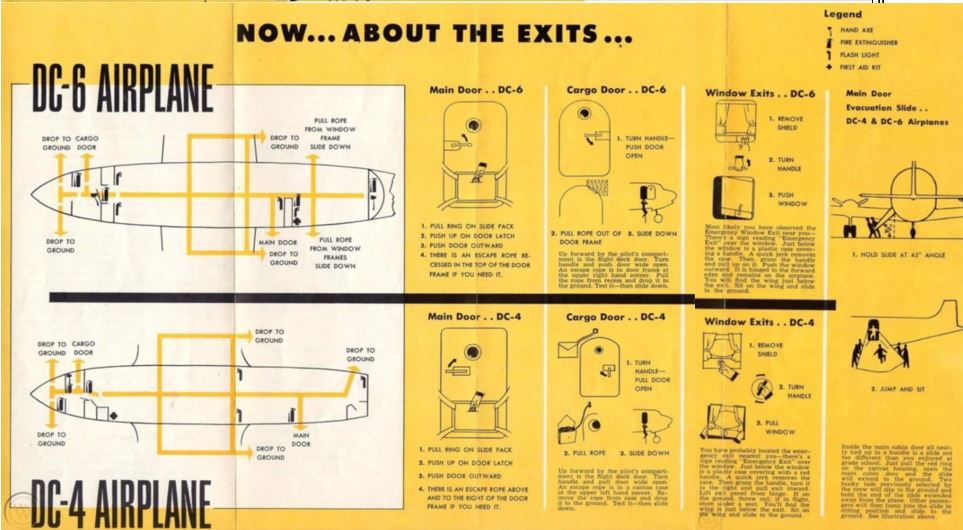

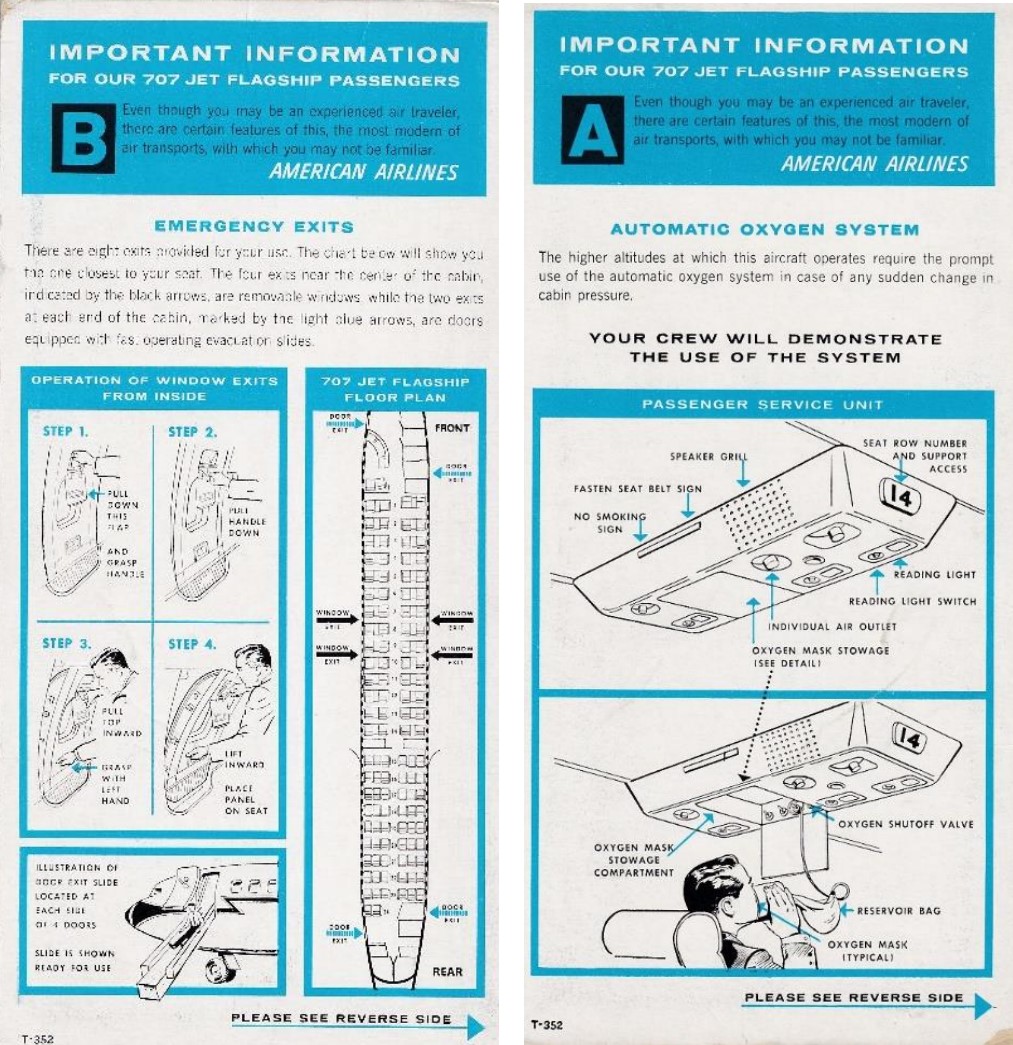

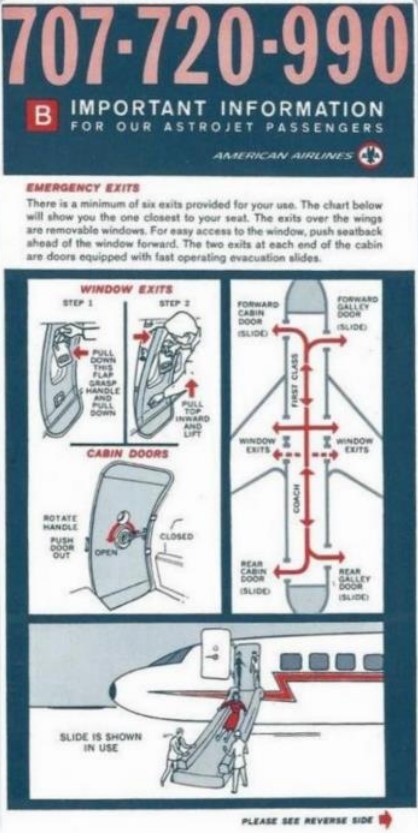

American Airlines (AA) was probably the first in safety information history to use a double-sided but unfolded heavy paper card. It is coded ‘T-352’ and is believed to be made for the introduction of the type in January 1959. Another AA innovation is to use graphics as the primary means of information, with text in a supportive role. That broke the industry standard of having text prevail with the occasional supporting graphic or photo. AA kept the information on the card to a minimum: an aircraft layout with all seats and exit locations/window exit operation/illustration of a deployed slide/an explanation of the passenger service unit and the automatic oxygen system. There were neither emergency preparation instructions nor brace positions. Also, there was nothing about life vests or rafts, but that matched the route pattern of AA which was then domestic-USA only. Only one language was needed: English.

Curiously, all exits are marked with arrows that point inwards. Only later became it custom to have arrows pointing outwards, in the direction of escape!

TWA, which introduced their first jet only two months after AA, also came with a double-sided, unfolded card for their 707. This was laminated, which would be a first. The presentation was similar to that of AA, minus the window exit, but with the supporting text appearing in four languages. The window exit and PSU/oxygen illustrations closely resemble those of AA, so was likely provided by Boeing.

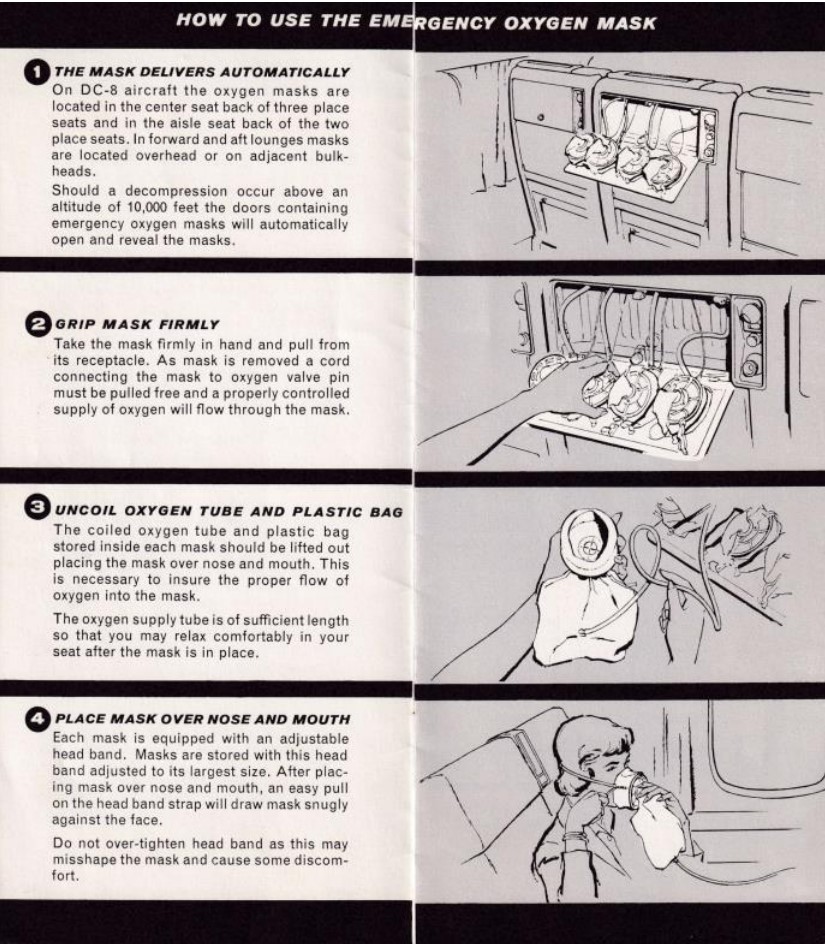

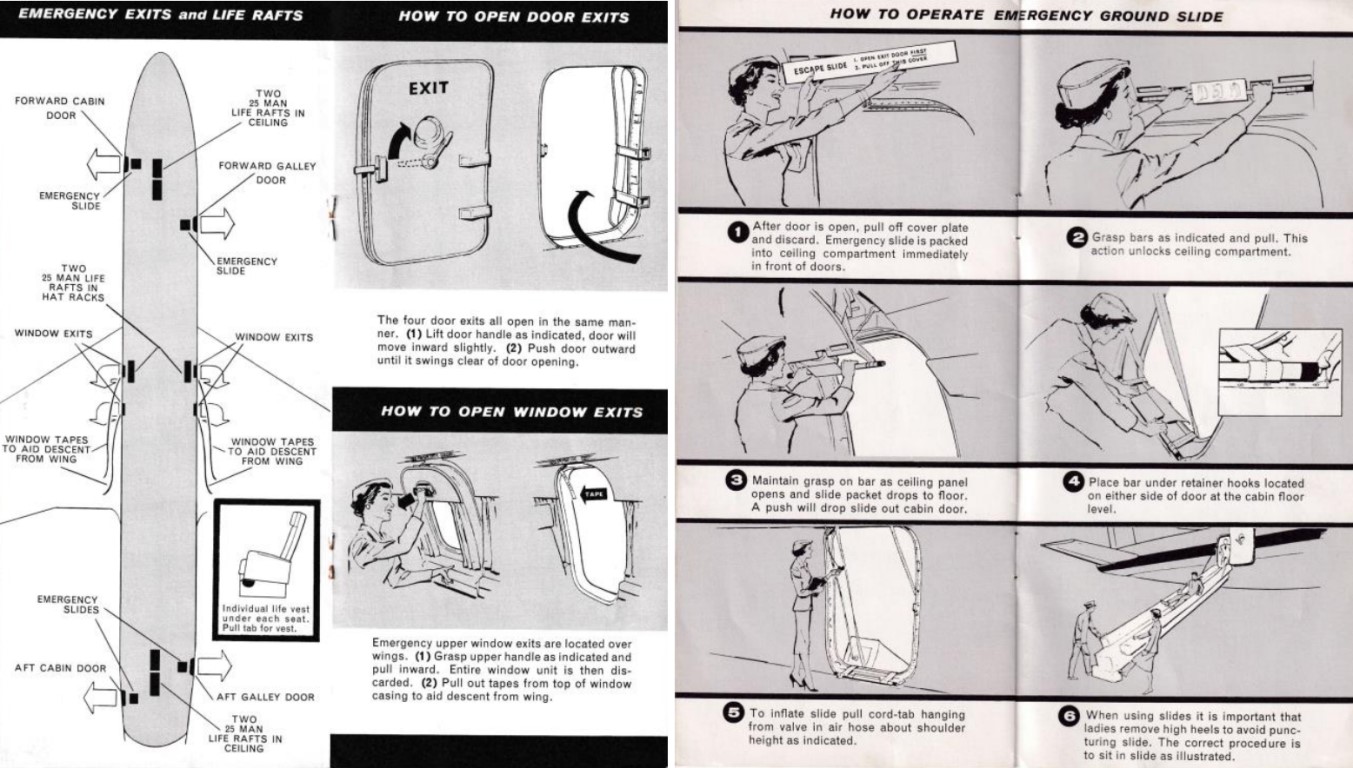

United, already known for its very detailed safety information (see previous part), continued that policy for their new DC-8s and Boeing 720s. In its eight-page 1959 DC-8 folder, it uses a mix of illustrations and text, e.g. to explain how to use the seat-mounted oxygen masks.

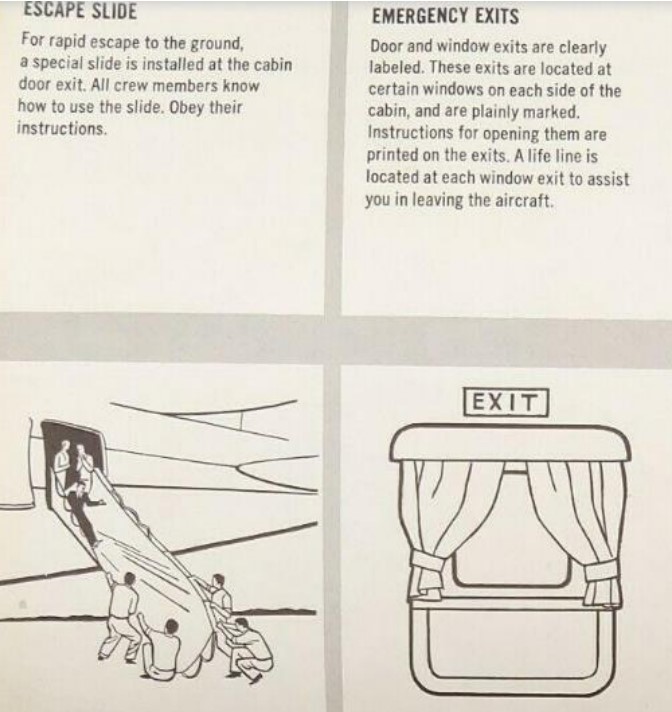

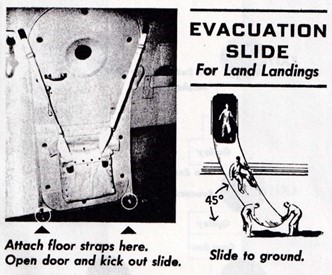

In 1953, United became the first airline to show how to open and use exits and continued as the first to do so for the jets. No other airline at the time showed how to open door exits (as opposed to window exits) and, in detail, how to attach and inflate the escape slides. In early DC-8s (and 707/720s) these were ceiling mounted and required quite a few actions before being operational. The illustrations shown are from the 1961 overwater DC-8 booklet edition, but the 1959 folder fielded the same.

Qantas and Cathay

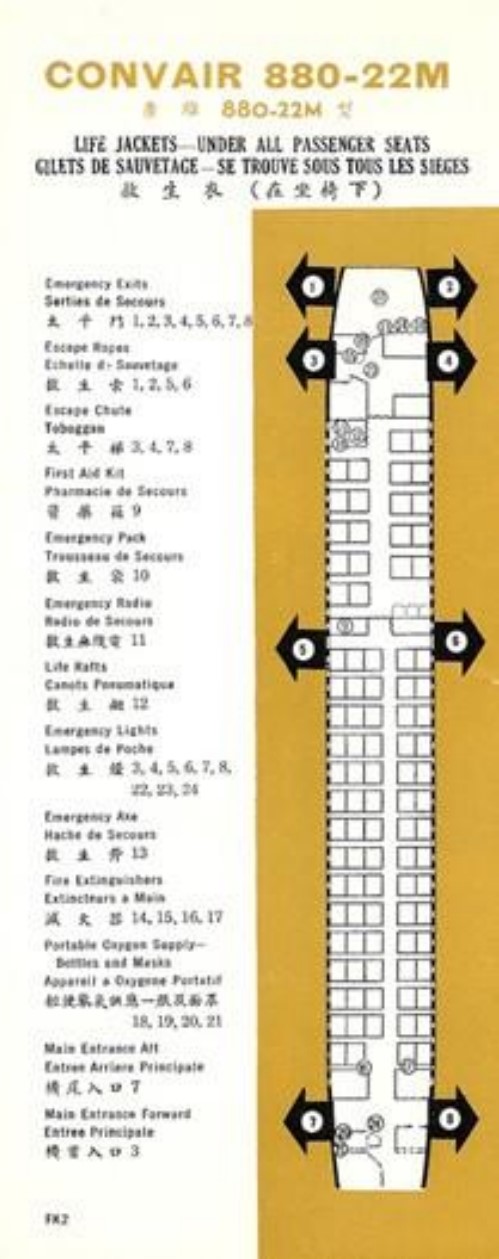

I’d like to share the details of two more leaflets. They are from two airlines deep in the eastern hemisphere: Qantas from Australia and Cathay Pacific from Hong Kong. Both do not fit the patterns described above as their leaflets are neither next iterations of a series, nor truly novel. Yet they are of interest as they have some features not seen elsewhere. They are from a Qantas 707 leaflet c. 1963 and from a Cathay Pacific fleet leaflet that dates from around 1966.

Both show emergency equipment locations, a practice not applied widely in those days. Cathay included the cockpit windows of their Convairs as emergency exits for passengers. This wasn’t something widely-practiced then, although some other Convair 880 operators did it as well, perhaps on instigation by Convair.

Qantas ordered the smallest 707 variant (which was even smaller than the 720), but I doubt whether their fuselage tapering was indeed as shown. Boeing was very keen on keeping constant diameter cabins, so perhaps Qantas’ artist was still a bit distracted by the curvatures of the 707’s predecessor, the Lockheed Super Constellation.

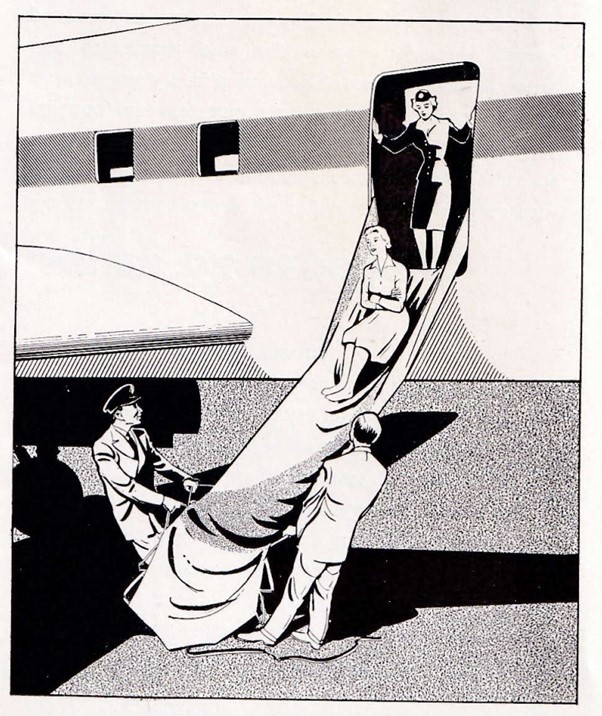

Qantas explained the use of the escape slides on their new jets by comparing them to, what looks to me, as a playground slide. Qantas explains that they “operate on the same principle as a slippery dip, or in the French translation: toboggan de plage, which, in turn, translates as beach slide.”

Trends

The turn of the decade 1950s/1960s was not only marked by the introduction of the jets but also by increasing awareness that many accidents were survivable and passengers needed education on matters other than ditching. As a result, there were quite a few changes in what safety information was given to passengers and how it was presented. Let me summarize the main trends.

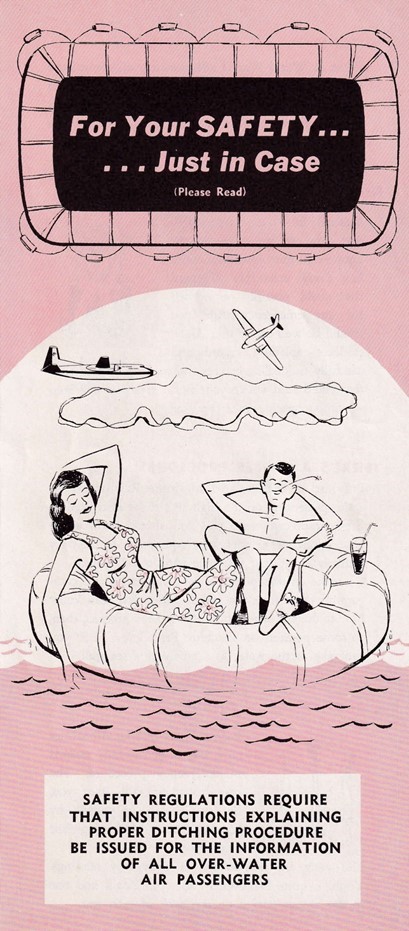

Less water, more land

As mentioned, in the 1950s it was realized that the ditching scenario was not unique in being survivable. Crash landings on land became more frequent and often turned out to be survived as well. The safety leaflets, booklets, and cards started to reflect this and the long lists of preparation for a ditching were replaced by information on opening window exits and using escape slides. Some major airlines that did not fly overwater and had never provided safety cards now started to do so. Life jacket and life raft information remained, but for overwater operations only.

Less reliance on crew, more self-help

Before, leaflets stated the crew would open exits and passengers had to obey their orders. An evacuation would be led by them and no further guidance was provided. This example is by Air India.

In the new decade, passengers were called upon to take responsibility and help open exits. Opening instructions were given, especially for those exits near where they were seated. This was already recognized by TWA and United in the early 1940s (see previous part), but since then had faded away, perhaps overshadowed by the focus on ditching.

The new cards gave detailed floor plans (sometimes even showing all seats), evacuation routes, exit locations, and emergency exit operation. The jets brought automatic oxygen systems for which passenger education was considered essential. The cards were ideal for that, but as we have seen, not all airlines were ready for this so had to improvise by making impromptu cards.

Less text, more graphics

In the ditching years, text prevailed in the leaflets, often repeating the same message in many languages. PAWA and BOAC had up to eight different languages on their folders. This led to large folders with endless text in small print that even fond readers may have found hard to digest. The introduction of the jets coincided with illustrations replacing words. Text became of secondary purpose. This trend developed gradually into today’s graphics-only cards.

Fewer folders, more cards

More graphics and less text meant the large folders could be compressed on smaller but heavier paper. The term safety card started to become a reality.

Less fleets, more type-specific

A trend that was slightly less pronounced was that of single aircraft type leaflets/cards replacing entire fleet leaflets/cards. Many airlines still found it convenient to have a leaflet that would suit all the aircraft in their fleet. I estimate at the turn of the decade, about half of the airlines used fleet leaflets, sometimes showing up to five or six different aircraft types, such as BOAC and SAS as shown above. But how would passengers know which aircraft type they were on? Perhaps it was mentioned in their ticket folder or at the start of the flight, but would they remember that when consulting the card or worse, when they needed to heed its lessons?

Other airlines issued separate leaflets or cards per aircraft type, such as American Airlines and TWA. Interestingly, a hybrid form came into use, made possible by the fact that the trio of early US jets had the same exit pattern. American Airlines used one and the same card for the 707, 720, and 990, collectively called the Astrojet. The exit pair that did not exist on the 720 and 990 was dashed.

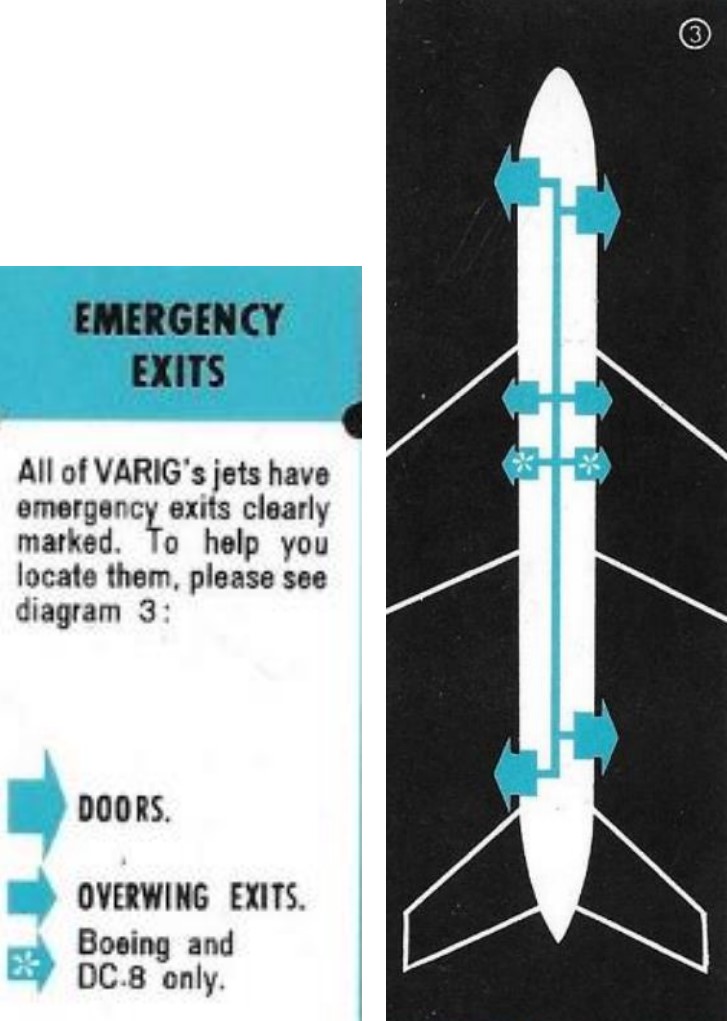

There was one airline that flew all three first-generation US jets: Varig from Brazil. This was not by careful fleet development choice, but rather by inheritance. Varig itself, in 1960, had bought the Boeing 707. When it took over REAL in 1961 it inherited its order for three Convair 990s. And when in 1965, Panair was amalgamated into Varig, its two DC-8s were added to Varig’s fleet. Varig used a single safety card for the three types. Only the asterisks on the aft pair of window exits, explained as ‘Boeing and DC-8 only,’ betray this was indeed the case. (see Brian Barron’s contribution for entire card).

Survivability issues

As the decade unfolded, jets became involved in accidents, some of which raised survivability issues. These triggered a host of cabin safety improvements later in the decade, including that safety cards were mandated by law. More about that in the next part.

August 2022

Email: f.schaefers@planet.nl