65 Years of Jet Travel

By David Keller

email: dkeller@airlinetimetables.com

facebook: facebook.com/airlinetimetables.comllc

website: http://airlinetimetables.com

blog: http://airlinetimetableblog.blogspot.com

______________________________________

May of 2017 marked the 65th anniversary of something we have long taken for granted, jet-powered air transportation. As much as air travel shrank the globe by cutting transit times from weeks (or months) to days, jets have further reduced those days to mere hours.

On May 2, 1952, the era of jet powered airline service began when a BOAC de Havilland Comet lifted off from London Airport enroute to Johannesburg via Rome, Beirut, Khartoum, Entebbe and Livingstone. The May 1, 1952 timetable shows this initial service, which arrived in Johannesburg on Saturday afternoon, departing on the return Monday morning.

As the world’s first jet transport, the Comet was trailblazer, operating at speeds and altitudes not attainable by propeller-driven aircraft of the day. As additional aircraft were delivered, design flaws began to take a toll, and in less than 2 years, 5 aircraft had been lost in accidents. The most devastating flaw was metal fatigue, which after only a few thousand cycles made the aircraft susceptible to explosive decompression while in flight.

The Comet would never recover its reputation after being grounded in 1954, despite the creation of a much-improved version in the late 1950’s. Comets returned to airline service in 1958 in the form of the Comet 4, but by then, superior models from Boeing and Douglas Aircraft were on the horizon, and only 76 Comet 4s were delivered.

The next jet transport to enter service was the Soviet Union’s Tupolev 104. This type had a design similarity with the Comet, in that the engines were placed inside the wing, near the fuselage. US manufacturers eschewed this engine placement in favor of suspending them from the wings on pylons, which reduced the likelihood of structural failure in the event of a fire, and I would imagine made them more accessible for maintenance.

Several hundred TU-104’s were built, with the type remaining in service with Aeroflot for roughly 30 years.

While these and other early jet transports played a role in the technological advances of commercial aviation, it was largely the US-built types that led to the rapid expansion of jet service across the globe. This article will highlight the jet service inaugurals of US trunk carriers, which all occurred in just over 2 years, as those companies raced to join the Jet Age.

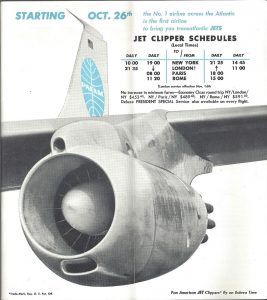

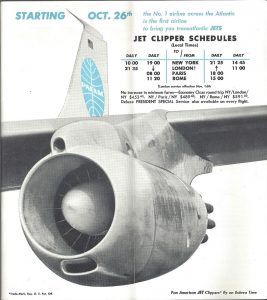

The aircraft widely considered to be the first successful jet transport was Boeing’s model 707. On October 28, 1958, Pan Am inaugurated 707 service, putting the type to work on the New York – Paris route. The timetable from this date has an image of the 707 wings and engines on the carrier’s traditional blue cover.

The gatefold has an ad promoting 707 service to Paris and Rome, with London starting a few weeks later. (In the timetable itself, it becomes evident that the continuing service from Paris to Rome was actually operated by a DC-6.) While most of the transatlantic services in this timetable were being operated by DC-7’s, the arrival of the Boeings meant the days of the Douglas piston types were numbered.

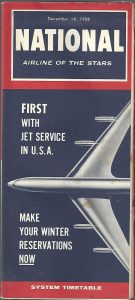

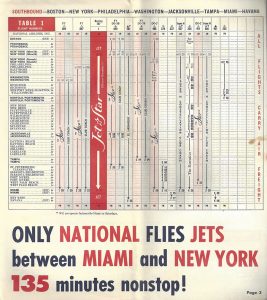

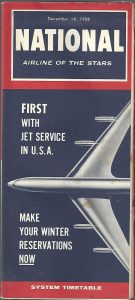

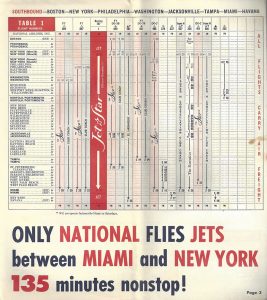

In December of 1958, National Airlines scored a coup by placing leased Pan Am 707s in service between New York and Miami, thus claiming the title of the first airline to offer domestic jet service in the United States. 707 flights were inaugurated on December 10, 1959, and the timetable dated December 14, 1959 shows 2 round trips being operated (one of which became effective on December 16th)

Flight timings meant that 2 different aircraft were required on any given day. But no 707’s were painted in National colors which likely means the aircraft were “wet-leased” and the actual ships on the Florida run varied from day to day.

In January, 1959, American Airlines inaugurated transcontinental 707 service. Further info and timetable scans were included in the previous Captain’s Log issue from earlier this year, so be sure to check out the article on American Airlines.

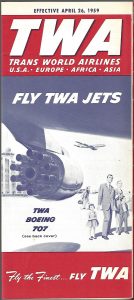

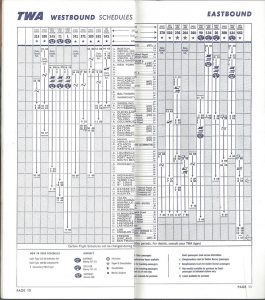

TWA was next with jets, also using them on transcontinental routes beginning in March of 1959. The timetable dated April 26, 1959 shows on the 707’s engines (which seemed to be popular subject matter for timetable covers), and advertises service between New York and Los Angeles/San Francisco, as well as between Chicago and Los Angeles.

Interestingly, the back cover of this timetable advertises Los Angeles to New York flight times as 4 hours and 55 minutes, while American inaugurated this route boasting of a 4 ½ hour flight time only a few months earlier. It seemed odd that TWA would be willing to concede a significant speed differential to its rival, particularly given the atmosphere of one-upmanship that prevailed as additional airlines acquired their first jets. However, a check of American’s timetable for the same date shows that the advertised flight time from Los Angeles to New York was also 4 hours, 55 minutes. Part of this would have been attributed to the slowing of the Jetstream winds from winter to spring, but it also appears that the additional fuel burn required to maintain those very high cruise speeds was not worth the few minutes saved.

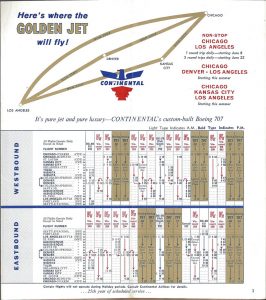

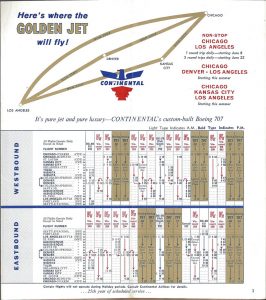

Continental Airlines’ April 26, 1959 timetable shows their initial 707 schedules, slated to begin on June 8th. A single round trip was operated between Los Angeles and Chicago, with 2 additional round trips being added on June 22nd. As with the previous airlines, Continental’s 707s were -120 models sporting non-fan engines. Not requiring transcontinental range, Continental would later opt for a fleet of medium range 720B fanjets that served until the mid-1970’s.

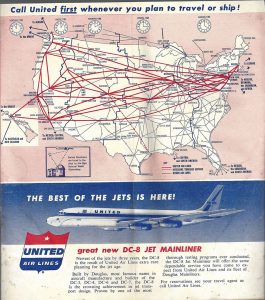

On this same date, April 26, 1959, the Sud Aviation Caravelle also entered service, with SAS being the first airline to operate the twinjet. The Caravelle was used primarily in Europe, although United Air Lines did order 20 aircraft, putting them into service in July, 1961. As the timetable dated February 1, 1963 shows, United used the Caravelle largely on the former Capital Airlines routes, from the East Coast as far west as Minneapolis/St. Paul, and along the eastern seaboard, as far south as Miami.

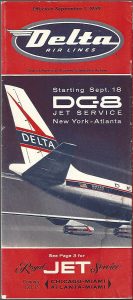

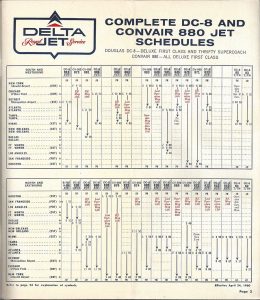

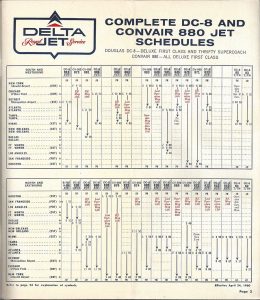

Almost a year after the 707’s entry into service, its primary competitor, the Douglas DC-8 began scheduled flights. As advertised on Delta Air Lines’ September 1, 1959 timetable, the carrier started DC-8 service on the 18th of that month. Two round trips between Idlewild Airport in New York and Atlanta were initially operated, with the aircraft overnighting on the East Coast. In mid-October, an aircraft originating in Miami began nonstop service to both Chicago and Atlanta.

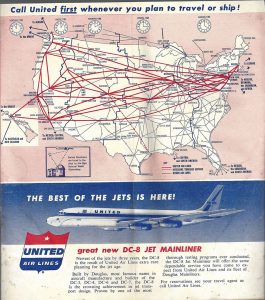

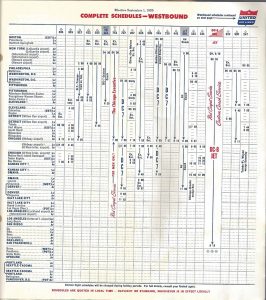

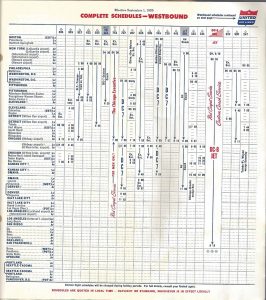

In a virtually simultaneous entry into service, United Air Lines also put the DC-8 to work on September 18th, operating between San Francisco and New York. Owing to the fact that United’s first jet service departed from the West Coast, Delta’s initial departure was several hours ahead of United’s. Both airlines were operating series -10’s, most of which were upgraded to -20’s or fanjet-powered -50’s shortly thereafter.

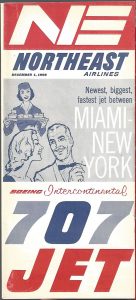

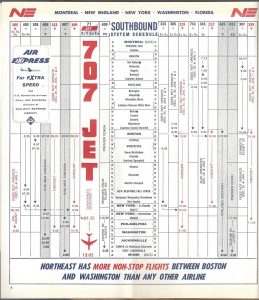

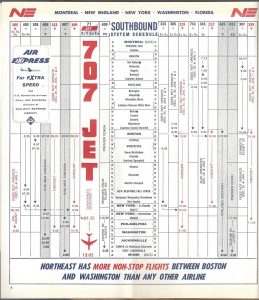

Already having been upstaged by National Airlines on the New York – Miami route the previous winter, Northeast Airlines leased a Boeing 707-320 series aircraft from TWA for the 1959 Winter season. The December 1, 1959 timetable shows a single roundtrip beginning December 17th, which was operated 6 times weekly, with no service on Tuesday.

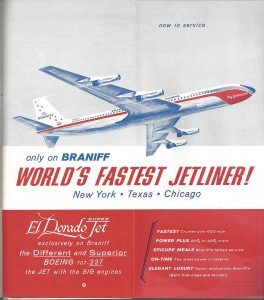

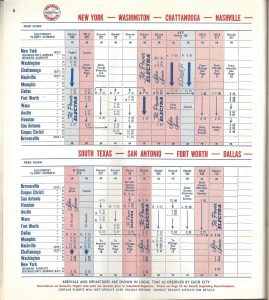

In late 1959, Braniff International Airways placed its “Different and Superior Boeing 707-227”s into service. The 707-220 model combined the fuselage of the -120 with the larger wings and more powerful engines offered on the -320 series. Braniff was the only customer, ordering 5 examples.

The first, N7071, crashed during flight testing prior to delivery, although that registration appeared on the carrier’s artwork for several years afterwards. The remaining 4 aircraft were delivered and served over a decade with Braniff before being traded to BWIA for 727s in the early 1970’s. Braniff had something of a penchant for oddball models of the 707, as they also acquired 4 short-bodied 707-138Bs from Qantas in the late 1960s.

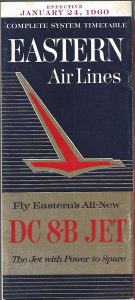

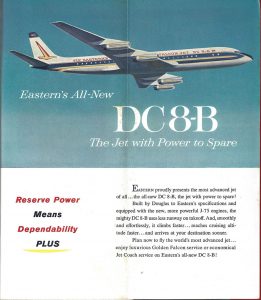

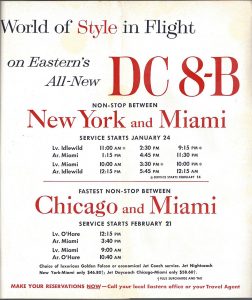

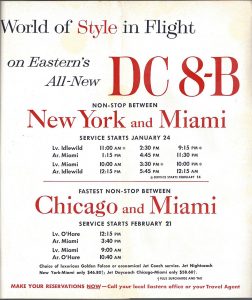

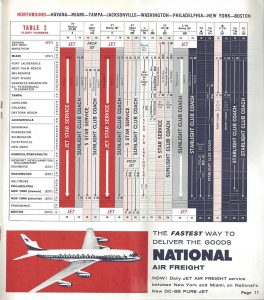

Eastern Airlines’ January 24, 1960 timetable shows the carrier’s initial jet service on what was obviously one of the most hotly contested markets in the nation, New York to Miami. Being a bit late to the party, 4 roundtrips were being offered, with 2 more being added in February. Eastern’s DC-8’s were delivered as -20s, initially referred to by the airline as DC-8Bs, sticking with the nomenclature used for Douglas’ piston transports.

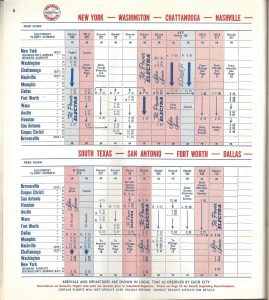

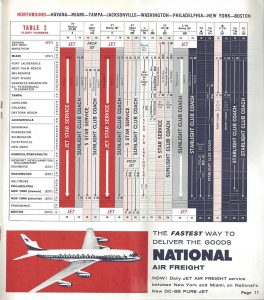

Another airline to start service with DC-8-20 series aircraft in 1960 was National Airlines. The carrier’s April 24, 1960 timetable shows the discontinuance of 707 services as of April 25th, with the DC-8’s assuming the pure jet duties. Flight segments between New York and Florida were scheduled for 10-20 minutes less with the Eights than with the Boeings.

The third player in the competition amongst US companies to build jet airliners was General Dynamics. The company had purchased Convair in the 1950’s, and attempted to win a significant portion of the market by offering aircraft that were faster than the Boeing or Douglas types.

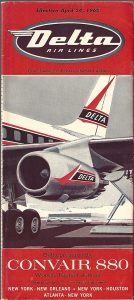

Delta Air Lines placed the Convair 880 into operation in May, 1960. As the timetable dated April 24, 1960 advertises, initial services were from New York to Atlanta, Houston and New Orleans. (The flight to Houston was scheduled to require 28 less minutes than the DC-8 previously used on the route.)

Additionally, Delta put the 880 into service with all “Deluxe First Class” seating, and utilized a special paint scheme that appeared on no other aircraft type. In less than 2 years, the Convairs were converted to a 2 class seating configuration, and they would eventually be repainted in the “widget” colors that were being applied to the entire fleet.

General Dynamic’s gamble with the Convair 880 (including further development into the model 990) did not pay off. The company had difficulty meeting performance guarantees, and the lower seating capacity and high fuel burn required for high cruise speeds resulted in just over 100 aircraft being built.

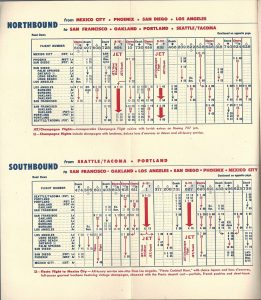

Western Airlines entry into the Jet Age came in the form of 2 707-120s which had originally been ordered by Cubana. These aircraft were leased to Western and entered service in the Summer of 1960. The June 1, 1960 timetable shows these aircraft operating 3 round trips between Los Angeles and Seattle, some via San Francisco or Portland.

As was the case with Continental Airlines, Western did not need the 707’s range, instead purchasing the smaller 720B. The 707s remained in the fleet for about 2 years, returning to Boeing as the 720Bs were delivered.

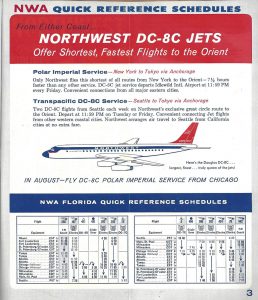

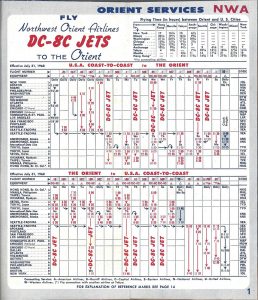

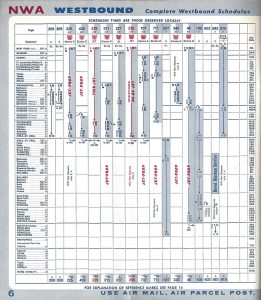

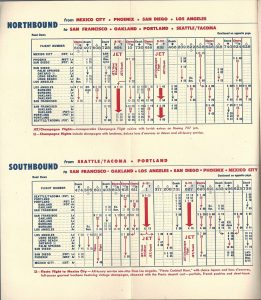

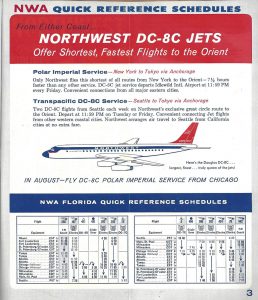

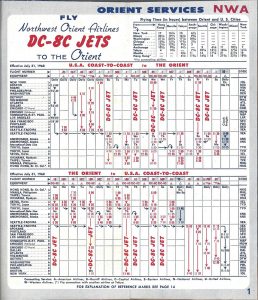

Bring up the rear of the pack was Northwest Orient Airlines, which started operating DC-8Cs (DC-8-30s) “to the Orient”. The July 1, 1960 timetable shows DC-8 service beginning on July 8th, primarily on flights between the US and Asia, thus requiring the longest range version of the aircraft available at the time.

Despite having been a loyal Douglas customer for many years, Northwest soured on the Eight, selling the entire fleet just a few years later as 707-320Bs from Boeing took over the TransPacific services. Northwest would not return to the DC- line until the DC-10 joined their fleet about 10 years later.

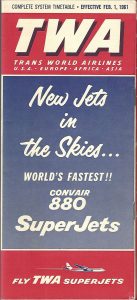

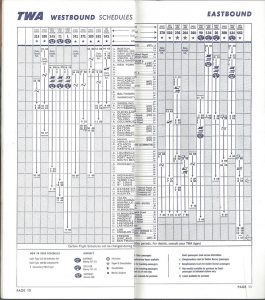

In 1961, TWA initiated Convair 880 service, on its way to becoming the type’s largest operator. The February 1, 1961 timetable shows 880s serving medium range routes to 8 cities. With the imposition of fuel quotas in 1974 that resulted from the Arab Oil Embargo of the previous year, there could no longer be any justification for retaining the fuel-guzzling jets, and TWA retired the fleet by the summer of 1974.

Although not the first jet in the fleet of any US trunk carrier, the Boeing 720 was notable for the number of those airlines it flew for. Boeing was able to create a slightly smaller, lighter version of the 707, albeit with a high degree of commonality between the two. (In fact, several airlines did not distinguish between 707s and 720s when specifying equipment in their timetables.) Every trunk airline that purchased 707s also operated 720s at some point (either purchased or leased), and given Douglas’ lack of an equivalent aircraft, 720s were also operated by United and Eastern, each having substantial DC-8 fleets.

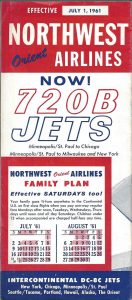

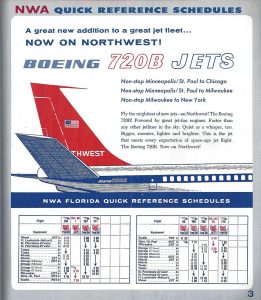

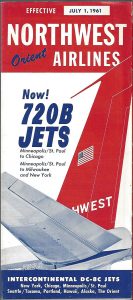

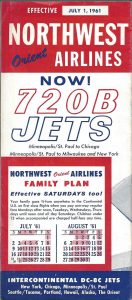

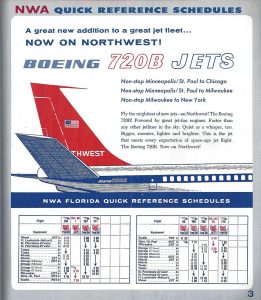

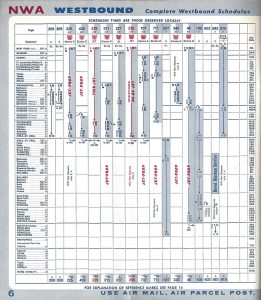

The July 1, 1961 Northwest Orient Airlines timetable shows the 720B entering the fleet with service from Minneapolis/St. Paul to Chicago, Milwaukee and New York. This paved the way for the 707s to take over the Asian services from the DC-8s, and it is my understanding that 720s were used to Asia on an interim basis until there were enough 707s available to operate the full schedule.

Despite being very popular in the early 60s, most of the trunks were quick to dispose of the 720Bs, phasing them out in the late 60s or early 70s, while keeping their 707s or DC-8s. Western Airlines was the primary exception, maintaining 720 service until the late 1970’s.

It is worthy to note that all of the 720 operators ordered large numbers of Boeing aircraft that was more suitable for medium range flights, the 727. In fact Eastern and United were 2 of the first customers.

65 years on, and some things remain largely the same. Fuselages are still long, roughly cylindrical compartments with passengers above, luggage and cargo below, a cockpit at the front and a tail at the rear. Most types still have jet engines suspended below the wings on pylons. Despite a trend from the 1960s to the 90s for rear- and/or tail-mounted engines, most of those are out of production and the vast majority of jets being built today have wing-mounted engines.

And yet, things are very different as well. Jet aircraft are much quieter, and no longer leave black exhaust trails to mark their passing. While 4 engines were pretty much a requirement in the early days (particularly for overwater flights), they are a liability in today’s environment. Boeing and Airbus struggle to find buyers for their 747 and A380 models, while pushing twin engine aircraft out the door at record rates.

In the never-ending desire to make aircraft lighter, manufacturers are making increasing use of carbon-fiber composites rather than traditional metals. In essence, some aircraft, such as the 787 and A350 are largely made of plastic.

And the long, narrow jet engines of the past have been superseded by gaping high-bypass turbofan engines. (The engine nacelles on the 777 are approximately the same diameter as the fuselage of a 737.) And those engines power aircraft on nonstop flights lasting up to 18 hours, a feat that would have required multiple stops for their predecessors.