Clipper,History,nautical,Pan Am,Pan American World Airways

The Nautical Airline

By James P. (Jamie) Baldwin

Pan American World Airways has always been associated with the sea and things nautical. Its aircraft were called “Clippers” and many of the Clipper names had references to the sea, particularly with the Boeing 747 aircraft, which were given names such as Pride of the Sea, Champion of the Seas, Spark of the Ocean, Belle of the Sea, Crest of the Wave and Sovereign of the Seas, to name a few.

How Pan American became the “Nautical Airline” is centered on Pan American’s founder, Juan Trippe who dreamed of this idea from the beginning of his venture in establishing an airline. How Pan American was formed is a story of wheeling and dealing, mergers and acquisitions and financial and political maneuvering that is well documented in the Pan American literature, including Robert Daley’s An American Saga – Juan Trippe and His Pan Am Empire (hereinafter “Daley”), Marylin Bender and Selig Altschul’s The Chosen Instrument (hereinafter “Bender and Altschul”) and R.E.G. Davies’ Pan Am, An Airline and Its Aircraft (hereinafter “Davies”).

Suffice it to say, however, it is useful to have a little background. In the beginning, there were four interested groups, as identified by Davies. The first group, the Montgomery Group, formed Pan American Airways, Inc. (PAA). It was founded on 14 March 1927 by Air Force Majors “Hap” Arnold, Carl Spaatz, and John H. Jouett, later joined by John K. Montgomery and Richard B. Bevier, as a counterbalance to German-owned carrier “SCADTA” (Colombo-German Aerial Transport Co) that had been operating in Colombia since 1920.

SCADTA was viewed as a possible German aerial threat to the Panama Canal. Eventually, Montgomery petitioned the US government to call for bids on a US airmail contract between Key West and Havana (FAM 4) and won the contract. However, PAA lacked any aircraft to perform the job and did not have landing rights in Cuba. Under the terms of the contract, PAA had to be flying by 19 October 1927.

On 2 June 1927, Juan Trippe formed the Aviation Corporation of America (ACA) (the Trippe Group) with financially powerful and politically well-connected backing and raised $300,000. On 1 July Reed Chambers and financier Richard Hoyt (the Chambers-Hoyt Group) formed Southeastern Airlines.

On 8 July Trippe formed Southern Airlines and on 11 October Southeastern was reincorporated as Atlantic, Gulf and Caribbean Airways. Trippe then proposed a merger between these three groups and in doing so played a trump card: He and John A. Hambleton, one of his backers, traveled to Cuba and persuaded the Cuban president to grant landing rights to the Aviation Corporation, making Montgomery’s mail contract useless as a bargaining chip. After much wrangling between the groups, including a meeting on Hoyt’s yacht during which Assistant Postmaster General Irving Grover threatened that if there was no deal he would not be awarding any contract to anyone, the Aviation Corporation of the Americas was formed, operating as Pan American Airways, headed by Juan Trippe. Later the corporation’s name was changed to Pan American Airways.

The deadline of 19 October still loomed, however. A Fokker F-VII aircraft was selected for the operation but could not be used because Meacham’s Field in Key West was not completed and could not accommodate the aircraft. What transpired was an eleventh-hour miracle. Pan American’s representative in Miami learned that a Fairchild FC-2 monoplane was in Key West, sitting out a hurricane threat. The aircraft was owned by West Indian Aerial Express (the Fairchild Group) and a deal was made to charter the aircraft. The pilot was offered $145.50 to carry mail to Havana that had just arrived on the Florida East Coast-Atlantic Coast Line railroads. The hurricane threat disappeared, and the trip was made. The rest is history.

On 28 October 1927, the Fokker left Key West on Pan American’s inaugural international flight, carrying 772 lb. of mail. On 16 January 1928, the first passenger flight was completed on the same route. And on 28 October 1928, Pan American established its Miami base at Dinner Key.

The First Clipper

In 1931, Pan American acquired the Sikorsky S-40, the first aircraft to be designated “Clipper”. This designation came about as a result of Trippe’s fascination with ships and the sea. As a child, he had traveled to Europe on Cunard Line ships and this fascination transcended to the idea that Pan American should be a kind of nautical airline.

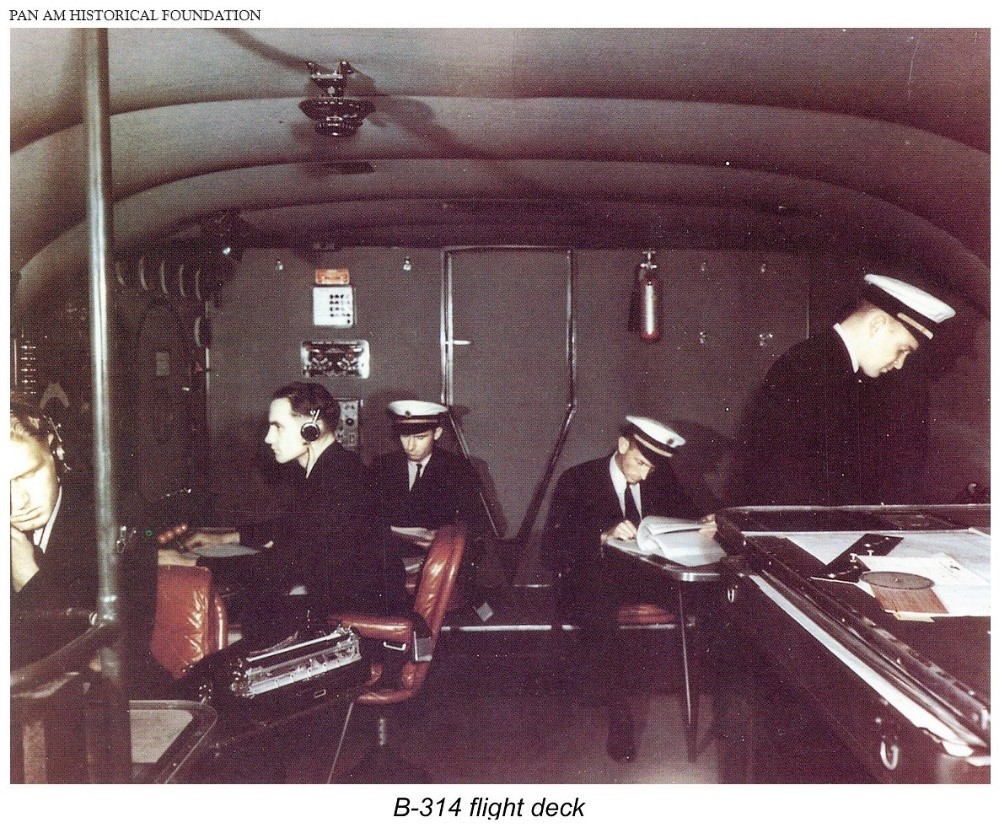

Along these lines, a maritime culture emerged. Andre Priester, who Trippe had previously hired as chief engineer, dressed the pilots as naval officers with gold wings pinned to their breast pockets. Gold stripes were on the jacket sleeves to show rank. The pilots also wore peaked hats with white covers and a gold strap. And, according to Daley, Priester “forbade [the pilots] to stuff or twist these caps into the dashing, high-peaked shapes so dear to most aviators’ hearts.” These naval trappings according to Bender and Altschul “served to set distance between the airline and aviation’s all too proximate history symbolized by the khaki breeches, leather puttees, jacket and helmet of the daredevil flyer. [Pan American’s] pilots were invested as engineers to whom flying was a scientific business rather than a thrilling escapade.” Pilots underwent a stringent and comprehensive training program and, according to former flying boat and retired captain Bill Nash, were required to have college degrees prior to hiring and to demonstrate proven proficiency prior to promotion in the flight deck. Nash started as a Fourth Officer before rising to Captain.

When the S-40 made its debut, it was the largest airplane built in the United States. Its maiden voyage on 19 November 1931 was from Miami to the Canal Zone carrying 32 passengers with Charles Lindbergh at the controls and Basil Rowe (formerly with the West Indian Aerial Express) as co-pilot. Igor Sikorsky, whom Trippe had earlier brought on board to design an aircraft to Pan American’s own specifications (the predecessor to the S-40, the S-38) also had some time at the controls.

Trippe named the aircraft the American Clipper. Perhaps inspired by prints of American Clipper ships hanging in his home or reaching back to his Maryland ancestry from where these swift sailing ships originated in the shipyards of Baltimore, it was, according to Bender and Altschul “appropriate then, to call the first transport ship designed for international air commerce after those magnificent vessels.” Thereafter, all Pan American aircraft were to be designated Clippers.

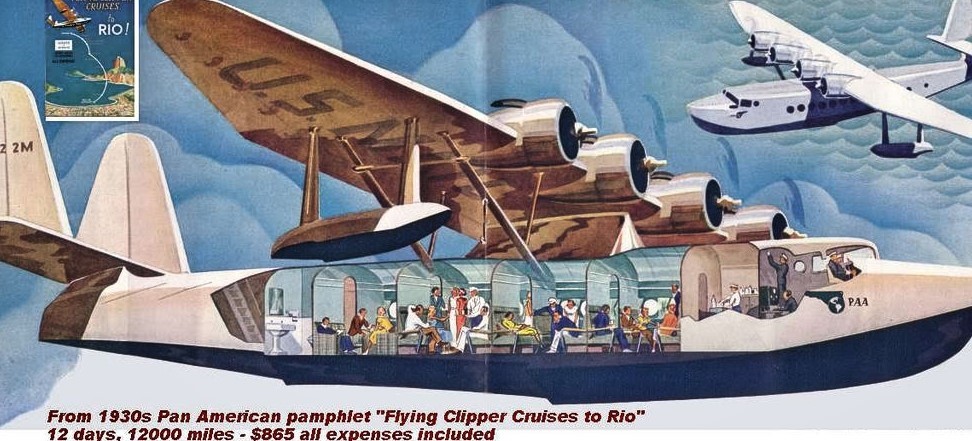

The operation would be in keeping with maritime lore and custom. The pilot was called “captain” and the co-pilot “first officer”. The title “captain” implied master of the ship or chief executive of the flying boat. Speed was calculated in knots (nautical miles per hour), time in bells, and a crew’s tour of duty was a “watch”. In the cabin, according to Daley, “walls and ceilings would be finished in walnut painted in a dark stain, and the fifty passengers would sit in Queen Anne chairs upholstered in blue and orange. The carpet would be blue, and the windows equipped with rope blinds. As aboard any ship, life rings would hang from the walls of the lounge.” The stewards, according to Bender and Altschul, “were modeled in function and appearance after the personnel of luxury ocean liners. Their uniforms were black trousers and white waist-length jackets over white shirts and black neckties. Stewards distributed remedies for airsickness, served refreshments (and in the S-40, prepared hot meals in the galley of the aircraft), pointed out scenic attractions from the windows of the plane and assisted with the red tape of Customs and landing procedures.”

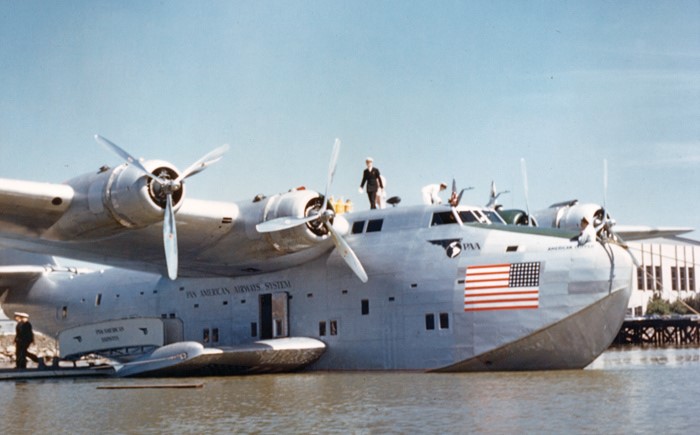

This nautical approach seemed to carry on through the entire existence of Pan American. The flight deck – bridge – was always on the top deck, as on an ocean liner. This was evident in the flying boats, including the Martin M-130, the China Clipper, the Boeing 314, the Boeing 377 Stratocruiser and the Boeing 747, with its flight deck on the upper deck of the aircraft.

The flight deck of the Boeing 314 had the appearance of the bridge of a merchant ship:

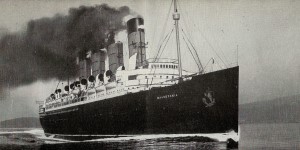

Below, the SS United States and the bridge of a large merchant ship (bottom):

A “nautical” ambiance was also prevalent at Clipper departures, particularly from Dinner Key in Miami during the early years and Pan American’s Worldport at New York’s John F. Kennedy International Airport in the later years. There was an atmosphere like the departure of an ocean liner, with festivity, sense of adventure, and anticipation of a voyage to a distant place. The setting at the Worldport, particularly with the evening departures to distant destinations, included passengers and well-wishers gathered at the gate in sight of the Clipper being readied for the long voyage ahead. There was a sense of drama; the type of drama that Juan Trippe probably envisaged for each Clipper departure. The romance of traveling to faraway places was part and parcel of the Pan American experience.

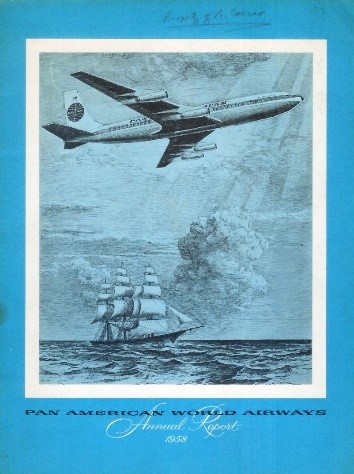

The nautical element was also featured in many of Pan American’s printed brochures and posters, as well as on the cover of an annual report.

However, as the years passed, the romance of the “nautical airline” began to wear out. Perhaps Pan American tried to preserve it with the Boeing 747, but times had changed. The grand ocean liners were soon replaced by cruise ships where passengers were more interested in the on-board entertainment rather than the peaceful environment of the sea (although that can still be experienced on cargo ships). Airline passengers became more interested in getting from A to B at the lowest fare, rather than experiencing the ambiance of a flying ocean liner. Airplanes became more like buses, apart from the premium cabins, rather than airships commanding the airways. And the bridge, both on many cruise ships and on the largest passenger aircraft in the world, would no longer be on the topmost deck. The sense of command of the airways and the sea has seemed to disappear, and the bridge, “formerly sacrosanct navigational preserves”, as eloquently described by John Maxtone-Graham in Liners to the Sun, is now simply a functionary in the process of getting passengers from A to B, or in the case of a cruise ship, from A to A via port visits.

In the picture below of an Emirates Airline A380, note that the flight deck is located between the main and upper decks. Compare the flight deck location on the Boeing 747 and other earlier aircraft pictured above. And, on the newer cruise liners, the bridge is not on the highest deck, as shown here on the Holland America Line’s MS Koningsdam, where it is located four decks below the top deck.

Perhaps Pan American the Nautical Airline was overcome by its own success. One cannot, however, deny that the idea of a nautical airline was a necessary step in the process of shrinking the globe. Now, with today’s technology, it probably is no longer needed. Happily, one tradition of the nautical airline continues: The Pilot-in-Command of an airliner is still the “Captain”.

An interesting anecdote:

Like the Boeing 377 Stratocruiser and the Boeing 747 was to Pan American, so is the A380 to Emirates Airline.

In an interview with Emirates CEO Sir Tim Clark, Andreas Spaeth noted that “probably no other airline boss since Pan Am patriarch Juan Trippe in the 1950s and 1960s, who helped shape the all-important Boeing 747, was as influential regarding what aircraft manufacturers were bringing to market than Sir Tim, a role he excels and revels in.”

Clark recalled how his parents “enjoyed the Pan Am Stratocruiser – the lounge downstairs, the dining room at the back…”

In another interview with Sam Chui, Clark explained his fascination with the double-decker airplane:

“I used to fly on the Pan-Am Boeing 377 Stratocruiser as a child; I was looking around saying, yes, you know they’ve got lounges, they’ve got a dining room downstairs etc. So in all the years, we’ve got the A380 to where that was.”

In the Spaeth interview, he recalled one of his favorite all-time aviation memories, when he set eyes upon his first jumbo jet: “It was on January 22, 1970, when Pan Am brought the 747 to Heathrow for the first time. I was 20 years old and I managed to get access to the roof of a catering building with my girlfriend to watch it land. We were all stunned.”

Little did he know then that, ultimately, he himself would play an essential role in bringing an even bigger airliner to the world stage.

Follow this link to read the author’s biography.

Follow this link to learn more about the author’s book, Pan American World Airways: Images of a Great Airline, Second Edition.