AeroMech,AirLA,Allegheny Commuter,Atlantic Southeast,Bandierante,EMB-110,Embraer,PBA

THE EMBRAER EMB-110 BANDEIRANTE

By Robert G. Waldvogel

The Embraer EMB-110 is the story of a turboprop regional airliner, the aircraft manufacturer that was established to build it, and the foundation of the Brazilian aviation industry. Two people were instrumental during these developments: Ozires Silva and Max Holste. Previously, Embraer built various models of Piper aircraft under license and continued well into the 1970s.

The former, who served in the Brazilian Air Force, earned an engineering degree from the Aeronautical Institute of Technology in Brazil, and a master’s degree from the California Institute of Technology in the US. He was promoted to the CTA’s Institute of Research and Development at the Aeronautical Technical Center in 1964 and became the catalyst for the country’s first commercial aircraft.

The former, who served in the Brazilian Air Force, earned an engineering degree from the Aeronautical Institute of Technology in Brazil, and a master’s degree from the California Institute of Technology in the US. He was promoted to the CTA’s Institute of Research and Development at the Aeronautical Technical Center in 1964 and became the catalyst for the country’s first commercial aircraft.

“The CTA’s market research showed that a vacancy existed in a market segment in what would later become known as “feeder lines,” according to Jeffrey L. Rodengen in The History of Embraer (Wright Stuff Enterprises, Inc., 2009, p. 36). “The research also revealed that airlines served just 45 Brazilian communities by the 1960s compared with 360 a decade ago.”

What was needed was a simple, rugged, reliable, low-capacity airplane that could operate from small-community, unprepared airfields that generated low-traffic demand, yet be profitable on short sectors characterized by comparatively high ratios of climb and descent to inflight cruise profiles.

The result was the IPD-6504, a low, straight-wing, twin-turboprop, conventional tail, retractable undercarriage design capable of carrying a dozen passengers.

Although its assembly began in 1966, conditions were hardly ideal: funding was rechanneled from other projects to breathe financial life into the transport, and only a single computer existed at the CTA’s campus three miles away. In order to avoid interference with student use, it was usually used throughout the night. The IPD-6504 designation also sounded too industrial.

To provide it with a better-sounding name, CTA Director Colonel Paulo Victor da Silva re-designated it “Bandeirante”—or “Pioneer”—to reflect the country’s 17th-century settlers who colonized the western portion of Brazil. As what would later prove to be the first of Brazil’s turboprop and pure-jet airliner designs, it served in a pioneering role of its own.

Taking to the sky for the first time two years later on October 22, 1968, it rose into the air after a short acceleration run, at which time the numerous witnesses of the historic event raised their arms in unison “to commemorate a moment that was ours alone,” Ozires Silva later commented.

Two other prototypes respectively first flew on October 19, 1969, and June 26, 1970. All three were Pratt and Whitney PT6A-20-powered and featured circular passenger windows and partially exposed main undercarriage wheels in the retracted position. They were alternatively designated YC-95s for military use.

Integral to it was the aircraft manufacturer that was established to produce it, Empresa Brasileira de Aeronautica, or Embraer, which was approved by Brazilian Congress decree 770 on August 19, 1969, creating the country’s first state-owned concern, located in São José dos Campos.

“Since the beginning, the successful Bandeirante prototype served to inspire Brazil’s aviation ambitions,” according to Rodengen (ibid, p. 39).

While Max Holste left the project two months before Embraer’s approval was granted, the aircraft’s development continued to be led by his deputy.

Aside from Brazilian Air force C-95 orders, the Chilean Navy also operated three aircraft.

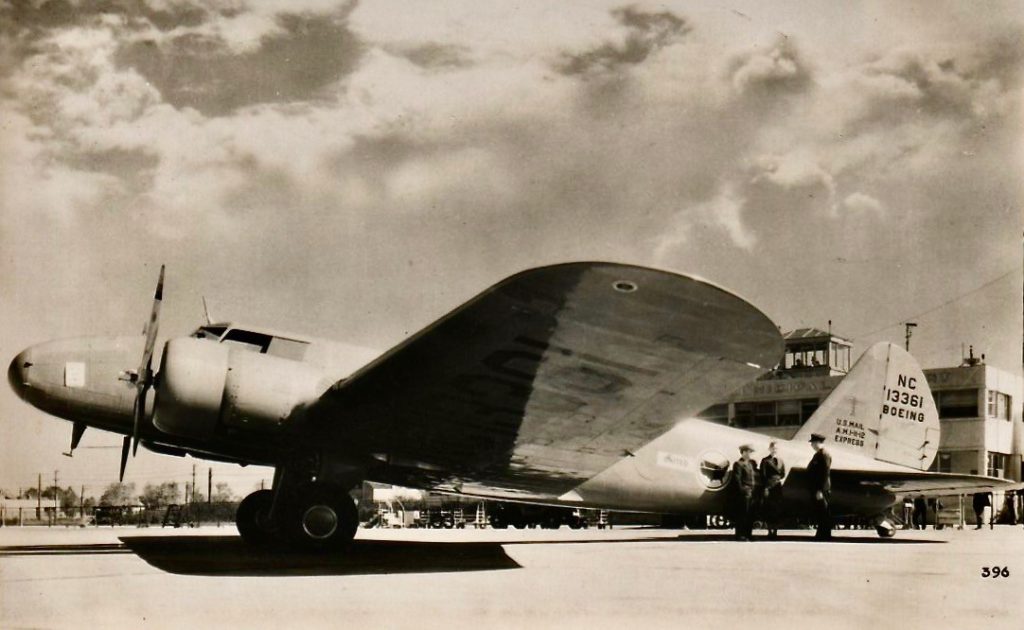

Reflecting its new manufacturer, the re-designated EMB-110, in production form, introduced several improvements, including 680-shp PT6A-27 turboprops that drove constant-speed, reversible-pitch propellers, a slightly longer fuselage with square passenger windows, a more aerodynamic windscreen, redesigned wings with integral fuel tanks, fries-type ailerons, double-slotted trailing edge flaps and modified engine nacelles in which the retracted main wheels were now fully enclosed.

Its single-wheel tires were developed by Goodyear’s Brazilian division and its cockpit was equipped with a Rockwell Collins Automatic Direction Finder (ADF) and a Very High Frequency Omni-Directional Range (VOR). It first flew on August 9, 1973.

Powered by PT6A-27 turboprops, the commercial EMB-110C featured a 46-foot, 8.25-inch overall length; a 15-passenger capacity, an aft left downward-hinged air-stair, a 50.3-foot wingspan with a corresponding 312-square-foot area and a 12,345-pound gross weight. Range depended upon ratios of payload to fuel, increasing from 153 miles with the former to 1,379 miles with the latter. Speed was 262 mph at 15,000 feet.

Transbrasil, the launch customer, ordered six aircraft and VASP followed suit with an order for five in 1973.

Rio Sul, another Brazilian commuter carrier, proved instrumental in demonstrating the aircraft’s design merits to potential customers. Whenever airline representatives visited Embraer’s São José dos Campos facility, they would be flown to the airline’s headquarters so that they could observe its reliable operation firsthand.

The Uruguayan Air Force became the EMB-110C’s first export customer when it purchased five in 1975. (See illustration below).

Rectifying its principal deficiency, the EMB-110P1 introduced an 18-passenger interior, configured with six three-breast, one-two-arranged seats with an offset aisle, and 750-shp PT6A-34 engines optimizing it for commuter or third-level airline operations. Belem, Brazil-based TABA (Transportes Aereas de Bacia Amazonica) became its launch customer.

Several variants of the baseline version were produced. The EMB-110A, of which two were operated by the Brazilian Air Force, incorporated navaid calibration instrumentation. The EMB-110B was an aerial photography platform. The EMB-110E was an executive version, seating seven in a luxurious interior. The EMB-110F was a pure freighter and the EMB-110K facilitated bulky and outsize shipment loading through a large cargo door. The EMB-110S was a geophysical survey variant.

The EMB-110P2 was basically the same as the P1 with the exception that the large aft cargo door was replaced with a second airstair entrance door. Featuring the 49-foot, 6.5-inch length of the EMB-110P1, accommodation for 18-19 passengers in seven three-abreast rows, and 750-shp PT6A-34 engines, Both P1 and P2 versions were offered with a 12,500-pound gross weight or 5900KG (13,007 pound) gross weight. and first flew on May 3, 1977.

Sales often depended upon country of operation certification.

“Many of Embraer’s foreign markets already had domestic aviation manufacturers, often established decades earlier,” according to Rodengen (ibid, p. 70). “While the Embraer brand was becoming better known throughout the world, manufacturers based in the United Kingdom, France, Germany, and the United States already dominated their individual domestic markets.”

Because the Brazilian regional type had initially been influenced by French national Max Holste, it found its way “home,” to a degree, when it was awarded the French Direction Generale de l’AviationCivile (DGAC) certification, paving the way for its first European operation when local commuter carrier Air Littoral ordered two stretched EMB-110P2s on May 5, 1977. Air Ecosse followed suit.

Other European certifications led to orders by Air Wales, BritAir, and Kar-Air, and Air Masling operated the type down-under when the Australian Department of Transportation granted its own type approval.

Gateway to the US market and FAA certification was Robert “Bob” Terry, who founded Mountain West Airlines, ordered three EMB-110P1s, and established the type’s sales agent, Aero Industries. Wyoming Airlines also ordered the Brazilian regional aircraft.

On the east coast, Connecticut-based NewAir, which was originally known as New Haven Airways, linked the state with the major New York airports, billing itself as “Connecticut’s Airline Connection,” as well as serving Islip’s Long Island MacArthur Airport, Philadelphia, and Washington-National. Some 20-weekday roundtrips, requiring 30 minutes for the aerial hop over Long Island Sound with its 18-passenger EMB-110s, connected New Haven and New London/Groton with the Metropolitan New York area.

Dolphin Airways, later Dolphin Airlines, was a significant operator based in Tampa, FL. It served cities in Florida plus Savanna, GA, Charleston, SC, and New Orleans, LA from 1982-1984 as a businessman’s airline. In addition to a fleet of new EMB-110P1s delivered from the factory, short-term leases included a P2 (N614KC) and an older P1 (N101RA).

PBA Provincetown Boston Airlines operated EMB-110P1s throughout Florida as a direct competitor to Dolphin Airlines and absorbed much of the Dolphin fleet after the latter ceased operations in January 1984. Seasonally, PBA fed PEOPLExpress and later Continental Airlines flights at Newark International Airport with its Bandeirantes, linking Farmingdale’s Republic Airport with five daily roundtrips.

Atlantic Southeast Airlines and Aeromech were other significant east coast operators as well as American Central Airlines and Tennessee Airways covered the Midwest United States.

On the west coast, Imperial Airlines provided its own EMB-110 shuttle between Los Angeles and San Diego. United Express and Dash Air were other significant operators in the Western States.

United States airlines ultimately operated 130 Bandeirantes—or more than a quarter—of the 501 aircraft of all versions produced between 1968 and 1990.

The EMB-110 competed in the regional airliner market with the Swearingen Metroliner and Beechcraft 1900 series but, suffered from a shorter range, slower speed, lack of pressurization, and a higher fuel consumption. Its acquisition price was lower because of the lower cost of manufacturing products in Brazil. All of the competing 18-passenger commuter types could comfortably accommodate those passengers while the double seats in the Bandeirante were quite cramped for adults. Most operators later reduced the seating to a total of 15 individual seats. Its commuter versions, particularly, demonstrated low-maintenance requirements, reliable service, passenger and cargo configuration flexibility, and enabled its operators to serve low-demand routes from unprepared fields previously never having received scheduled service and it often became the first type in a fledgling carrier’s fleet, enabling it to expand.

Many EMB-110 Bandeirante operators replaced their fleets with EMB-120 Brasilias and later went on to operate EMB-135/145 regional jet airliners.

“The existence of the Bandeirante led to the creation of smaller regional air travel services in Brazil and around the world, a global market that Embraer has come to dominate, thanks in part to the specialized, flexible, resilient Bandeirante,” Rodengen concludes (ibid, p. 43).

Preserved in São José dos Campos, Brazil

Photo Courtesy: Raphael Albrecht.

Florianópolis Hercílio Luz International Airport (FLN) on July 7, 2016.

Photo courtesy of Bruno Orifino

Note: the short fuselage and rear passenger entry door on this early Bandeirante model.

Embraer EMB-110 P2, N614KC

Washington National Airport (DCA)

The P2 version had dual airstair doors instead of the large rear cargo door.

Photo Courtesy of Jay Selman via Airliners.net

Pictured at Cincinnati (CVG) in May 1982

Photo Courtesy: Charlie Pyles/Air Pix

Note: The rear airstair is lowered.

Pictured at Cincinnati (CVG) May 1983.

Photo Courtesy: Charlie Pyles/Air Pix

Embraer EMB-110 P1, N199PB seen at rest between flights.

Photo Courtesy of Ellis Chernoff

Note: the modified horizontal stabilizer came about as a result of a mysterious in-flight loss of a PBA Bandeirante with the standard tail plane becoming detached from the aircraft in flight.

As seen at Dallas/Ft. Worth (DFW) in 1987.

Photographer Unknown

Gary C. Orlando Slide Collection

Note: the standard Large Cargo Door found on the more widely produced P1 model.

Seen taxiing out from the Imperial Terminal at Los Angeles (LAX) in February 1993.

Gary C. Orlando Photo.

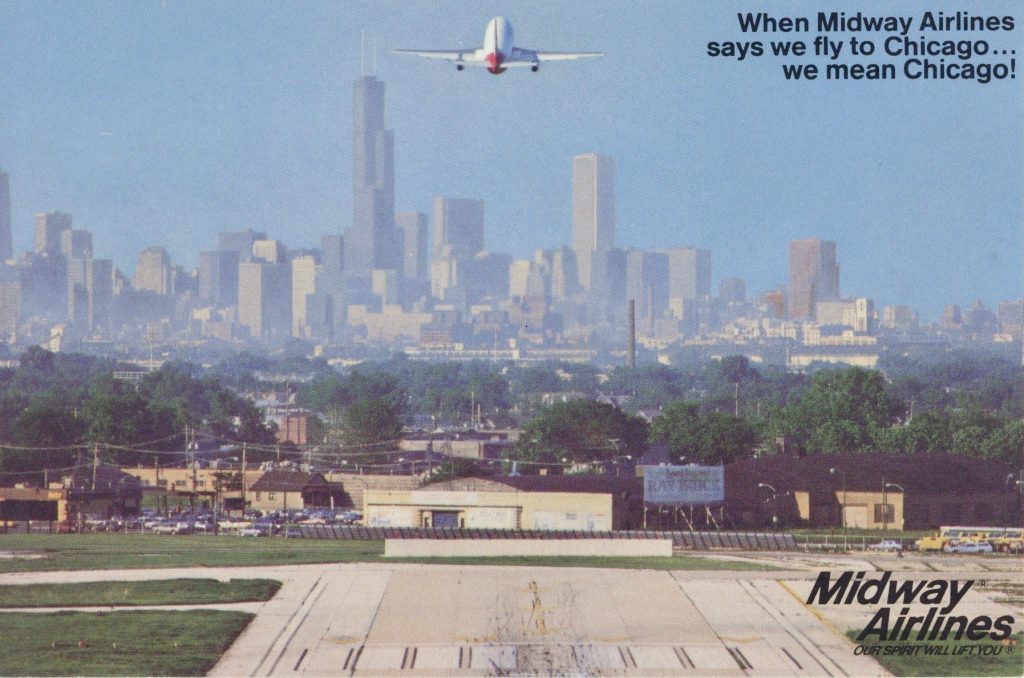

Originally delivered to Tennessee Airways, it passed to Iowa Airways where it flew as a Midway Connection carrier as evidenced by the livery.

EMB-110 Article Sources

Green, William, and Swanborough, Gordon. An Illustrated Guide to the World’s Airliners. New York: Arco Publishing, Inc., 1982.

Hardy, Michael. World Civil Aircraft Since 1945. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1979.

Rodengen, Jeffrey L. The History of Embraer. Ft. Lauderdale, Florida: Write Stuff Enterprises, Inc., 2009.

Waldvogel, Robert G. “The Airline History of Long Island’s Republic Airport.” Metropolitan Airport News. October 2021.

Waldvogel, Robert G. “The Commuter Airlines of Long Island MacArthur Airport.” EzineArticles. August 5, 2019.