Airliners International 2023,American Airlines,Amon Carter Field,Dallas,Delta Air Lines,DFW,Fort Worth,GSW,Love Field,Meacham Field,postcard contest,Southwest Airlines

Dallas – Fort Worth Airports on Postcards

By Marvin G. Goldman

In view of Airliners InternationalTM, the world’s largest airline history convention and airline collectibles show, to be held June 21-24, 2023, at Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport (DFW), this Captain’s Log “Postcard Corner” article describes the background and development of the major airports in Dallas/Fort Worth, illustrated by historic postcards.

The large cities of Dallas and Fort Worth, Texas, are located only slightly more than 30 miles (50 km) apart. Economically, it made sense to develop one major airport to serve both cities. However, numerous proposals from the 1920s on for such a combination all came to naught until 1968 when, at the insistence of the U.S. Federal Aviation Agency (FAA), the two cities agreed to jointly build a single major airport to serve the area encompassing both Dallas and Fort Worth. That airport became Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport (DFW), located equidistant between Dallas and Fort Worth, and today the second-busiest airport in the world by passenger numbers.

Prior to the agreement to build DFW, Fort Worth and Dallas both competed to develop the dominant airport in the area for scheduled commercial flights.

Fort Worth – Meacham Field

In 1925 the City of Fort Worth purchased Barron Field, a World War I-era aviation training field, and named it “Fort Worth Municipal Airport.” In 1927 the airport was renamed Meacham Field after former Fort Worth Mayor Henry C. Meacham. American Airways (later to become American Airlines) established its base at Meacham Field in 1927, and the airport became the main airport for commercial airlines in the Fort Worth-Dallas area.

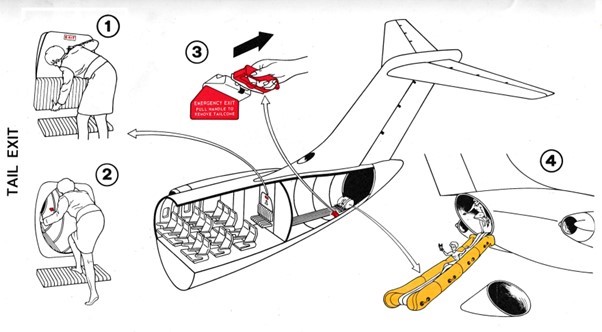

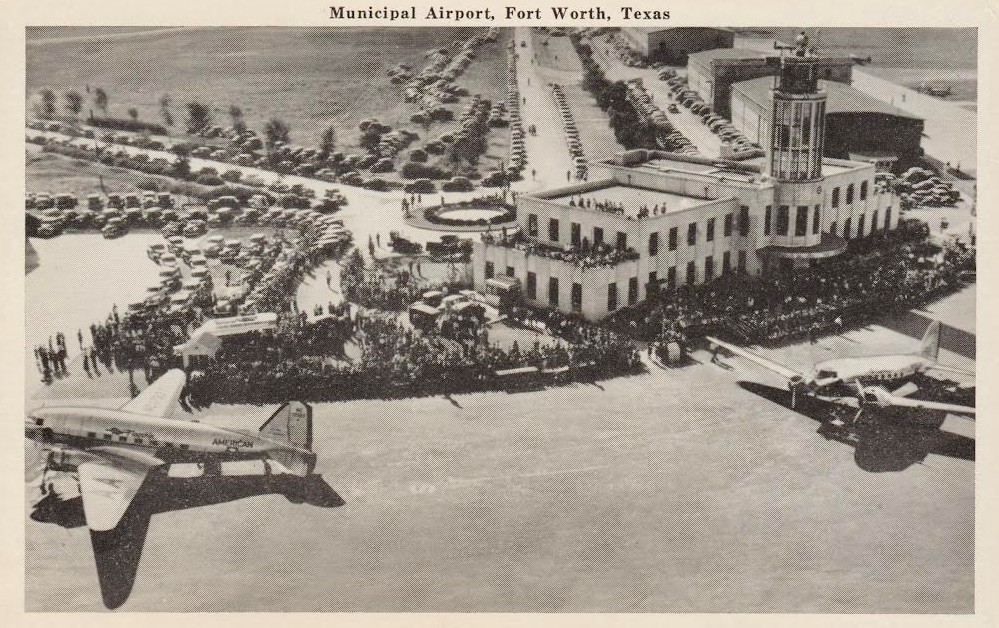

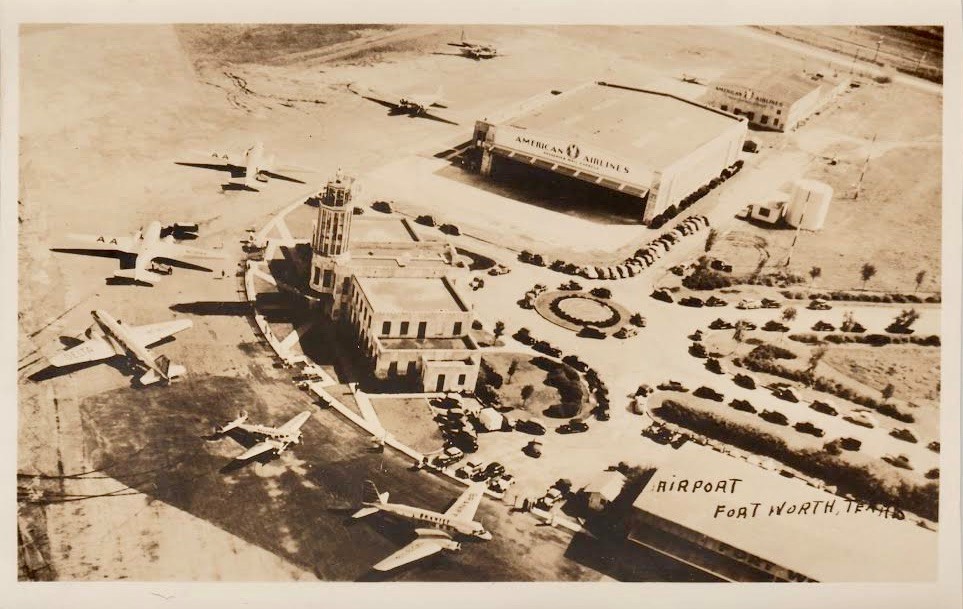

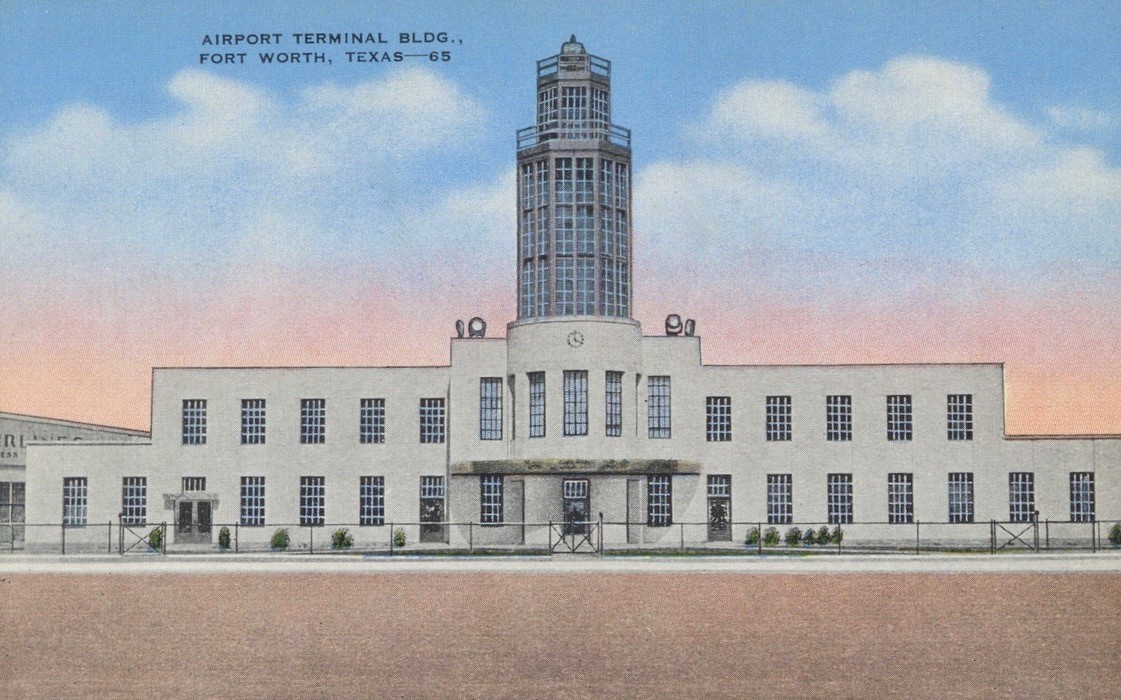

On April 4, 1937, Meacham Field dedicated a new terminal and control tower. The terminal was designed in the “Art Moderne” or new streamlined style, and it was the first air-conditioned passenger terminal in the U.S. Here is a selection of postcards showing Meacham Field and its new terminal.

with the newly built terminal and control tower in the background, probably in early 1937 before their completion.

Airline issue A-245-C.

On the ramp are two American Airlines Douglas DC-3s.

Publisher Graycraft Card Co., Danville VA, no. F-156.

Al Canales collection.

Other airlines utilizing Meacham were Central, Pioneer and Trans-Texas.

Real photo postcard.

Al Canales collection.

This was the first airport terminal in the U.S. with air conditioning.

Pub’r Atlas News Shop, Fort Worth; Printer E. C. Kropp Co., Milwaukee, nos. 65, 6945.

Greater Fort Worth Airport (Amon Carter Field; Greater Southwest Airport)

During the early 1940s, Fort Worth decided to develop a larger airport to handle rising air traffic and allow future expansion that was not possible at Meacham Field. The site selected for reconstruction was that of Arlington Municipal Airport. It was located at the eastern edge of Fort Worth and was almost equidistant between the centers of Fort Worth and Dallas. Fort Worth invited Dallas to jointly develop the site to serve both cities. However, as Dallas was developing its close-in airport Love Field and that airport was preferred by its residents, Dallas declined to participate. Ironically, this new Fort Worth site was located almost adjacent to what later became today’s Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport.

The new Fort Worth airport finally opened on April 25, 1953, and was named Greater Fort Worth International Airport at Amon Carter Field (Amon Carter was the Mayor of Fort Worth). Airlines then transferred from Meacham Field to the new airport, Since 1953, Meacham has been used by corporate aircraft, commuter flights, and for student pilot training.

In 1962 Fort Worth changed the name of its new airport to “Greater Southwest International Airport” as part of an effort to again entice the city of Dallas to join in further development of the airport. However, that overture was turned down as well.

Here are some postcards of Greater Fort Worth International Airport, also known as Amon Carter Field and, from 1962, as Greater Southwest International Airport.

Postmarked July 9, 1958.

Photographed and published by John A. Stryker, Fort Worth, no. ART-6293-2.

It was furnished in “modern western style” and finished in fine marble from Portugal.

The bas-relief murals on the left wall depicted early Texas history and were covered with 18-karat gold leaf.

Photographed and published by John A. Stryker, Fort Worth; printer Colourpicture, Boston, no. P5928.

Postcard image from the internet.

The reverse side states: “Looking from the south passenger loading concourse, one sees the east side of the main Airport Building and the north loading concourse….The main dining room of the terminal building and observation deck are on the left side with the air traffic control tower.” Photographed and published by John A. Stryker, Fort Worth; printed by Colourpicture, Boston, no. P6166.

I have seen one of these postcards postmarked January 1954.

Photographed and published by John A. Stryker, Fort Worth; printed by Colourpicture, no. P6167.

Love Field Municipal Airport, Dallas, Texas

While scheduled airline service and facilities at Fort Worth’s Meacham and then Amon Carter Fields grew relatively slowly, its neighboring larger city, Dallas, developed Love Field which grew faster because more passengers preferred its proximity to downtown Dallas.

Love Field originated in 1917 as the site of an aviation training base established by the U.S. Army Air Service during World War I. It was named after Lieutenant Moses L. Love, an early Army pilot who was killed during flight training at another site. In 1927 the City of Dallas purchased Love Field from the military to serve as its site for commercial air service which developed during the 1930s. After the end of World War II in 1945, Love Field grew expansively, reflecting significant increases in passenger traffic. By 1965 Love Field featured new terminals and a second parallel runway, effectively doubling its capacity, and its passenger numbers that year were, astoundingly, nearly 50 times those of Fort Worth’s airport.

Here is a selection of postcards featuring Dallas Love Field.

Printer Curteich, Chicago.

Pub’r Stellmacher & Son, Dallas, no. SC1900.

Airlines serving Love Field at that time included American, Braniff, Central, Continental, Delta, and Trans-Texas.

Airline and airport postcard collector Al Canales remarked in the Spring 2016 40th anniversary issue of the Captain’s Log, “[This is my] favorite postcard [of about 11,000 cards in my collection]. [It’s] not a rare one but one that brings back many happy memories of hours spent on that observation deck visible under the wing of the DC-7 doing what I truly enjoyed”.

Pub’r H.S. Crocker Co., Los Angeles, no, TPC-166; distributor Texas Post Card Co., Dallas.

Ex-Allan Van Wickler collection.

Pub’r All-Tom Corp., Dallas-Ft. Worth; printer Colourpicture no. P44211.

Note the mix of propeller and jet aircraft types, and a Continental Airlines Viscount turboprop on the taxiway.

Pub’r Texas Post Card & Novelty Co., Dallas; printed by Dexter Press, West Nyack NY, in 1961, as no. 43446-B.

Pub’r All-Tom Corporation, Arlington, Texas; printed by Dexter Press in 1967, no. D-21998-C.

Pub’r Mission Card Co., Dallas; printer Colourpicture, Boston, no. P74205.

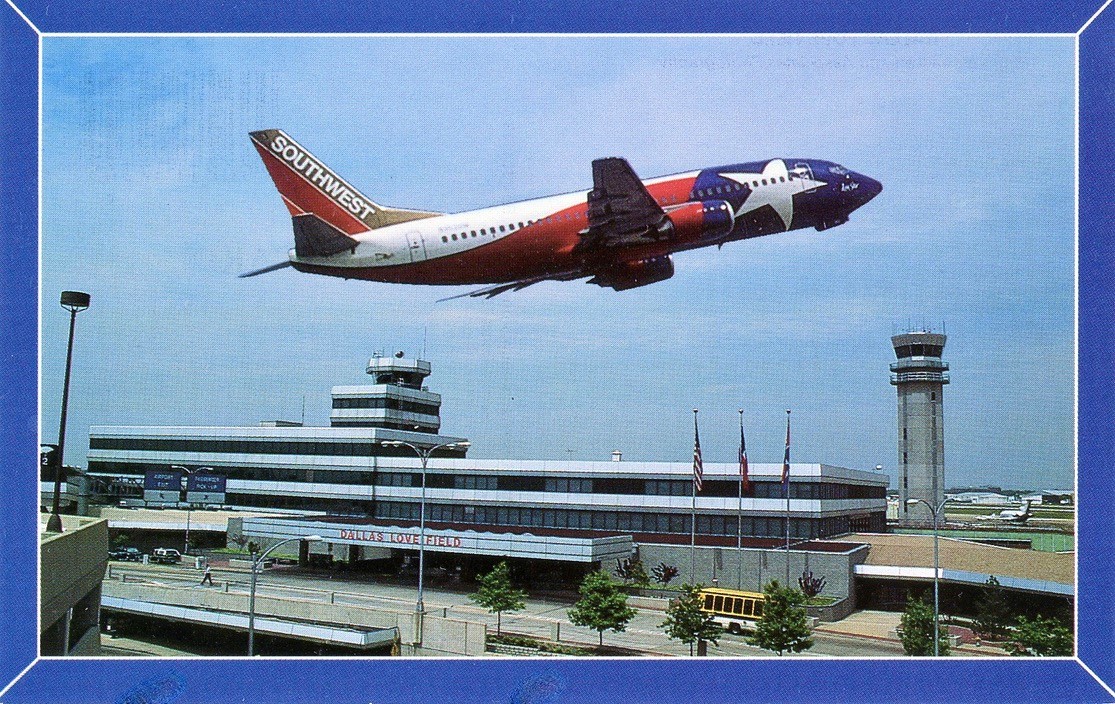

The aircraft image on this postcard is Southwest’s 737-300, N352SW, which entered its fleet in late 1990 and was painted in the “Lone Star One” livery, Southwest’s homage to its home state of Texas.

Photo by Sackett and Associates; pub’r A-W, Dallas, no. D-132; printer John Hinde Curteich.

Transition to Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport (DFW)

By 1965 Fort Worth’s Greater Southwest Airport at Amon Carter Field (GSW) was severely underutilized, while passengers and airline scheduled service flocked to Dallas Love Field which was bursting at the seams with air traffic and had insufficient room for expansion. The U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) decided it would no longer assist in funding improvements at two separate airports so close together. At the insistence of the FAA and the Civil Aeronautics Board, the two cities agreed to set aside their rivalry and jointly develop and operate a single larger and more modern airport equidistant between them. The agreement also provided that all airlines would have to move from GSW and Love Field to the new airport. The site chosen was a huge swath of undeveloped land just north of the Greater Southwest Airport. This is the site that became Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport – DFW. Ground was broken for the construction of DFW airport in 1968, and scheduled flights at DFW commenced on January 13, 1974.

Meanwhile, passenger traffic continued to sharply decline at GSW, and by 1969 all scheduled flights there had ceased. GSW continued in use for general aviation, some charter flights, commuter and air taxi traffic, and crew training, while also serving as a diversionary airport for Love Field. However, upon the opening of DFW in January 1974, GSW was closed. In 1979 GSW was sold for redevelopment as an industrial and office park, and its airport facilities were soon demolished. Today the headquarters of American Airlines’ parent company, AMR Corporation, is located where GSW’s terminal once stood, and American Airlines’ C. R. Smith Museum is opposite the GSW site.

Love Field continued its prominence while DFW was under construction. However, when DFW opened in 1974, all airlines – with one notable exception – moved their operations to DFW. The exception was Southwest Airlines which refused to move and prevailed on that issue in a lawsuit brought by the cities of Dallas and Fort Worth and the DFW Airport Board. Subsequently, Southwest fought several legal battles to lift restrictions imposed by the “Wright Amendment” on its ability to fly to destinations outside Texas. Full success was achieved in 2006 by a federal law that served to repeal the Wright restrictions. Since then, Southwest has financed several expansions of its facilities at Love Field, and it remains the dominant airline by far at Love Field. Other airlines currently operating scheduled flights there include Alaska Airlines and Delta Air Lines.

Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport – DFW

As mentioned above, DFW Airport opened to scheduled airline service on January 13, 1974, and all airlines except Southwest moved there from Love Field. With 27 square miles of land, DFW is the second largest airport in the U.S. by area (next to Denver); and with 72 million passengers in 2022, it is the second busiest airport in the world by passenger numbers (behind Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport – ATL). Presently, 28 airlines serve a total of about 260 destinations from DFW.

Commensurate with its growth in passenger numbers, DFW airport is continuously expanding its facilities. Most recently, DFW approved in 2021 a $2 billion project, to be completed by 2026, including the renovation and expansion of Terminal C serving American Airlines and the addition of gates at other terminals.

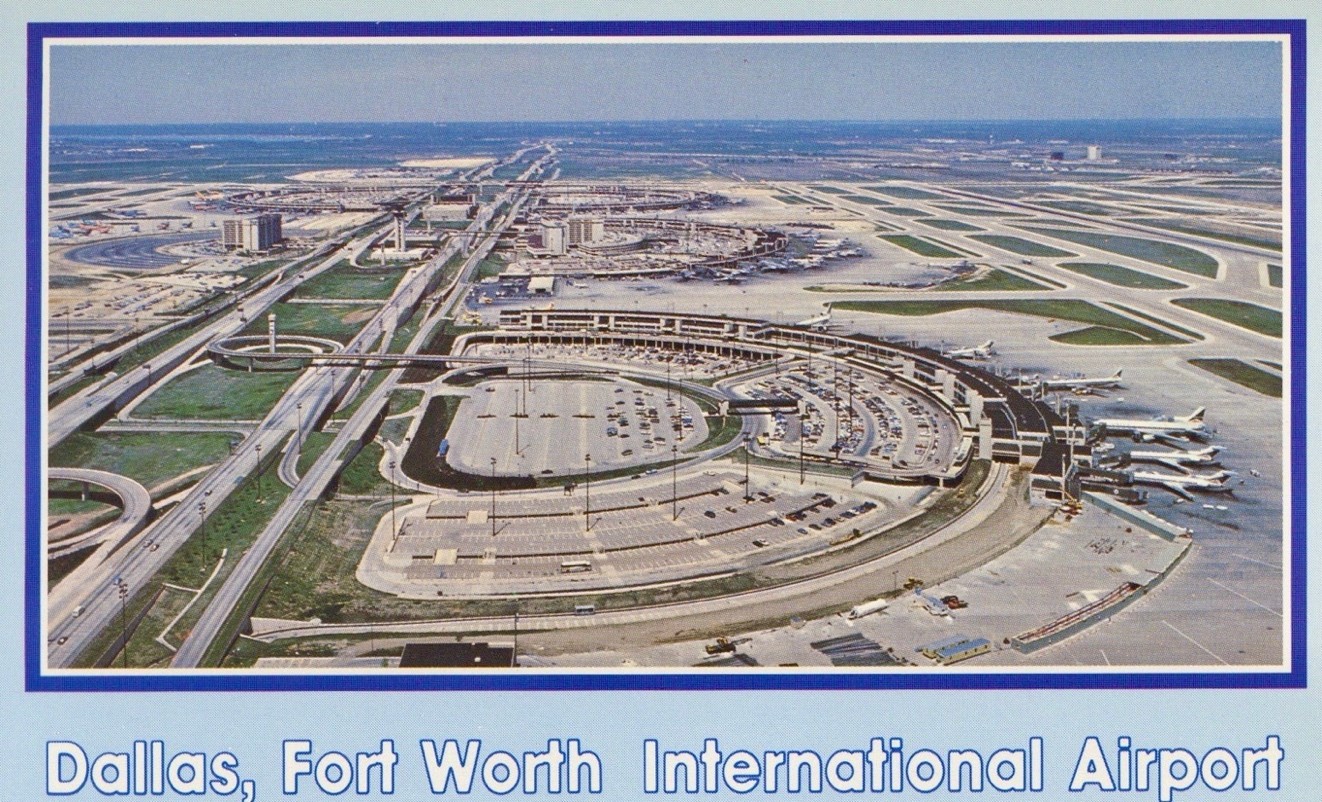

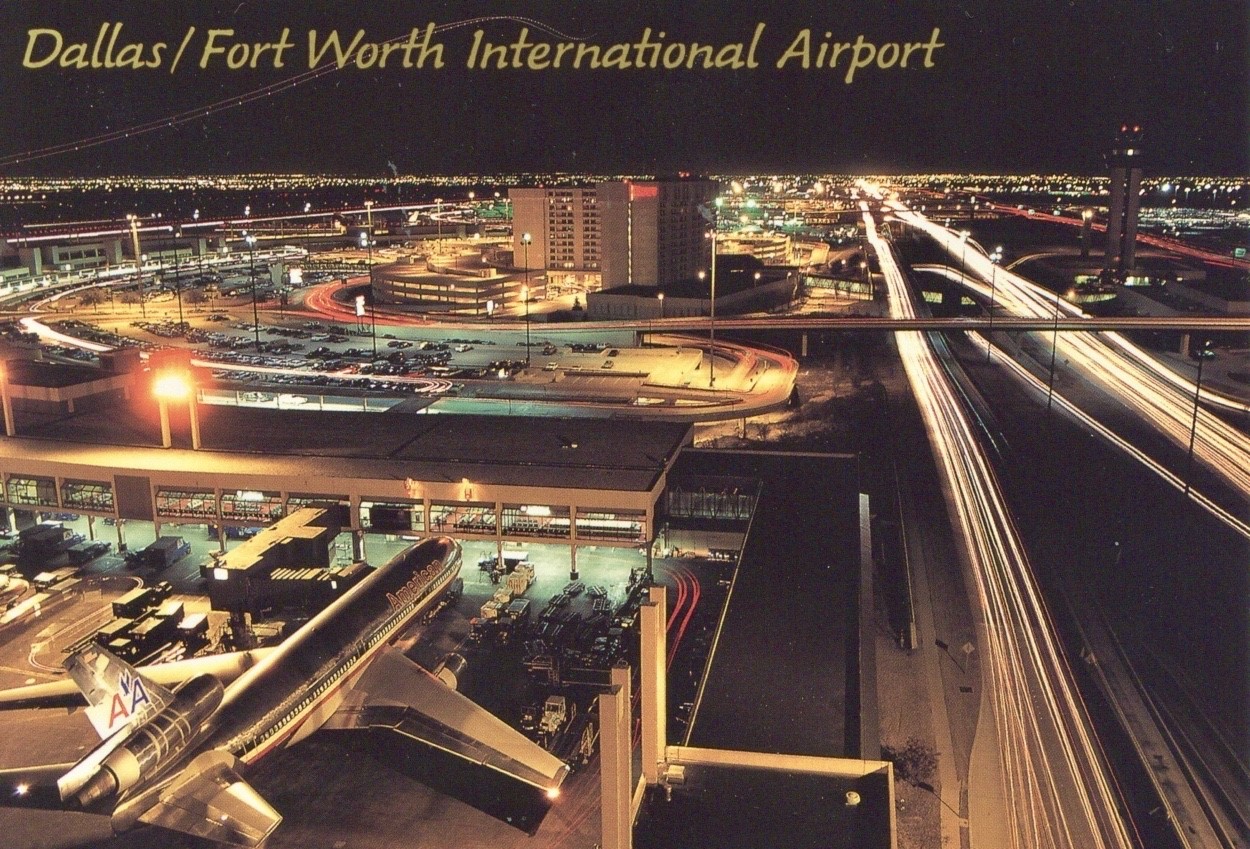

Here is a sampling of postcards showing DFW.

Pub’r The Texas Postcard Co., Plano, Texas, no. D-150, 711; photo by Raff Frano.

American Airlines utilizes DFW as its primary hub and its corporate headquarters and aviation museum are nearby.

In the upper center of this postcard, close to the control tower, is the Hyatt Regency Hotel, site of the Airliners InternationalTM airline history convention and airline collectibles show, June 21-24, 2023.

Published in 1981. Pub’r A.W. Distributors, Irving, Texas.

Pub’r Texas Postcard Co., Plano, Texas, no. /d-111; printer MCG, Kansas City, Missouri; photo by Gordon Smith.

Pub’r Texas Postcard Co., Plano, Texas, no. D-102; Joe Towers photo.

Notes

All the postcards shown in this article are from the author’s collection unless otherwise noted. My estimate of rarity: Rare: the two aerial views of Meacham Field; Uncommon; American Airlines at Meacham Field; Love Field with Trans-Texas and American aircraft; Love Field with Continental Viscount; and DFW Braniff terminal. The rest are fairly common.

References

- Cearley, Jr., George W. A Pictorial History of Airline Service at Dallas Love Field, 200 pp. (1989).

- Friedenzohn, Daniel. “DFW: The Texas-Size Airport,” Airways (Oct. 2003, pp. 32-37).

- http://www.airfields-freeman.com/tx/airfields_tx_ftworth_ne.htm (on Greater Fort Worth Airport).

- Airport websites: dfwairport.com; dallas-lovefield.com.

- Texas State Historical Association websites: tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/love field and tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/dallas-fort-worth-international airport.

- Wikipedia articles on “Fort Worth Meacham International Airport,” “Greater Southwest International Airport,” “Dallas Love Field,” and “Dallas Fort Worth International Airport.”

Airliners International 2023 DFW

I hope to see you at Airliners International™ 2023 DFW, June 21-24, 2023, at the Hyatt Regency Hotel, next to Terminal C at Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport. This is the world’s largest airline history and airline collectibles show and convention, with more than 200 vendor tables for buying, selling, and swapping airline memorabilia (including, of course, airline and airport postcards), seminars, the annual meeting of the World Airline Historical Society, annual banquet, tours and more.

I hope you’ll consider entering the Postcard Contest at the AI 2023 show. More information and contest rules are available by clicking this link: airlinersinternational.org.

Until then, Happy collecting. Marvin

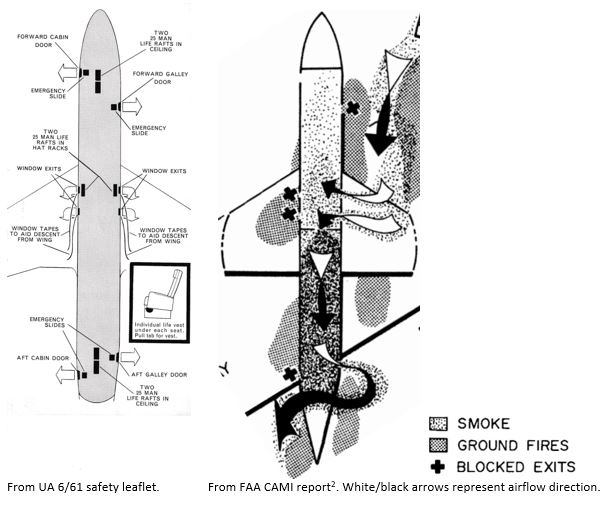

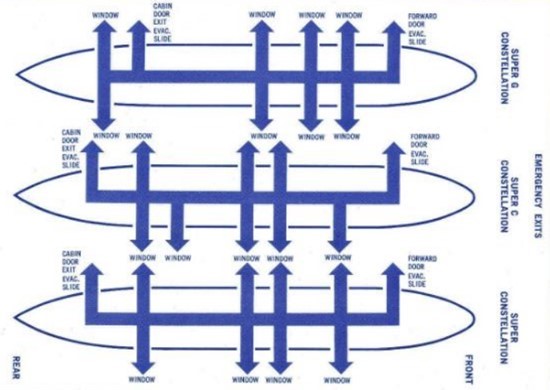

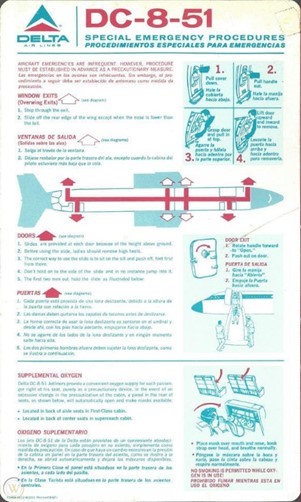

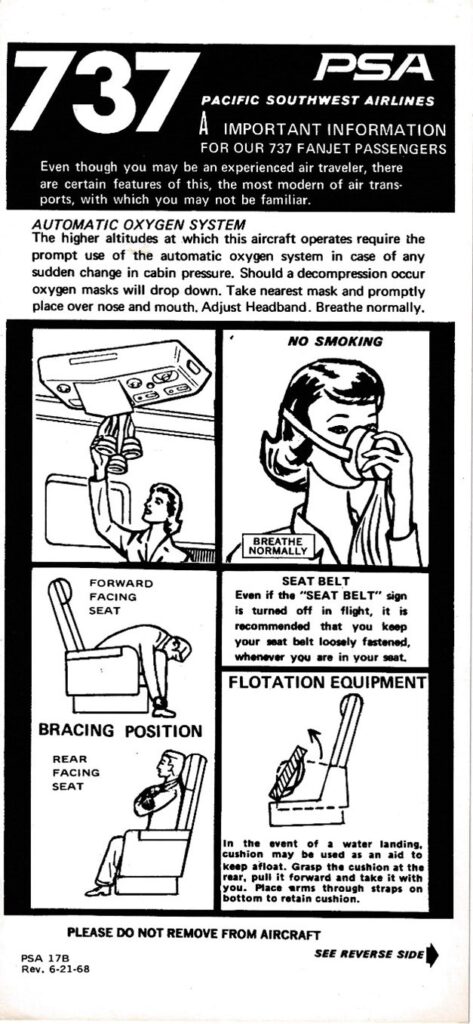

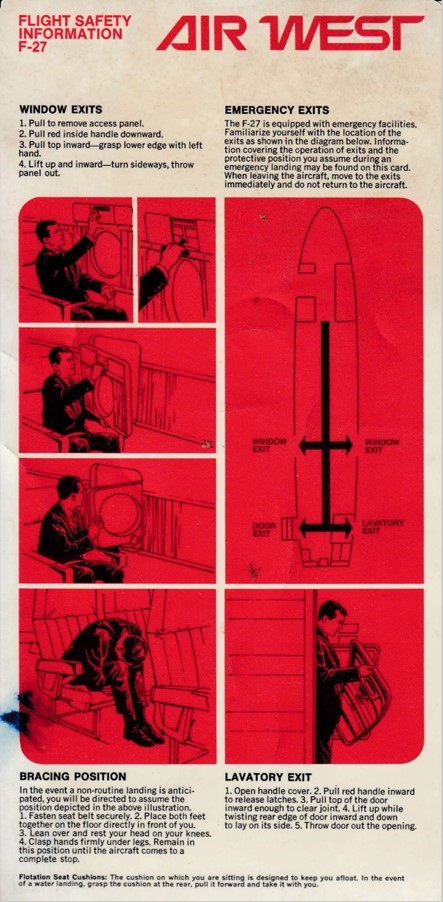

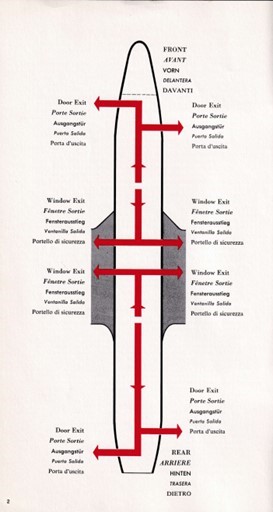

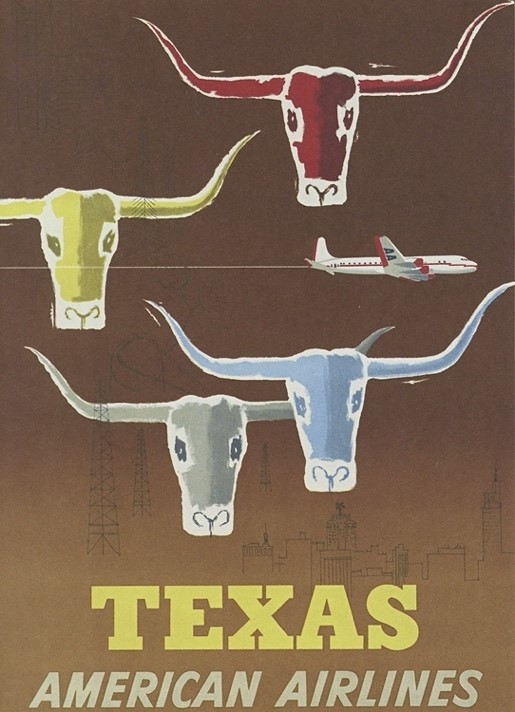

Part of a set of historic posters in postcard form believed to have been issued several years ago by American Airlines’ C. R. Smith Museum, Dallas.