The Space, Grace, and Pace of a Sandringham Flight

By Fons Schaefers

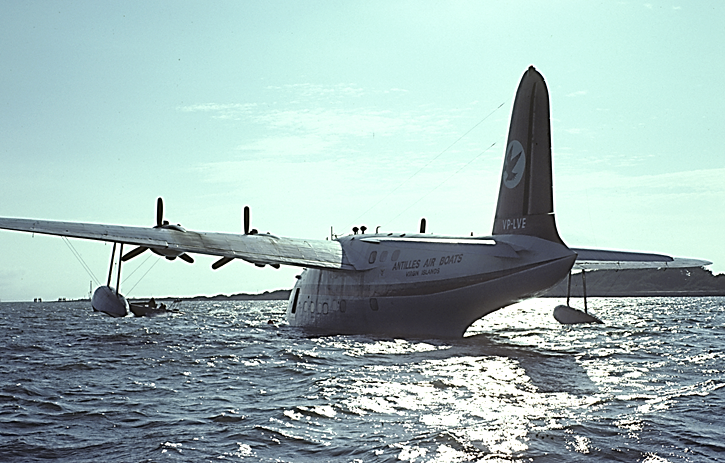

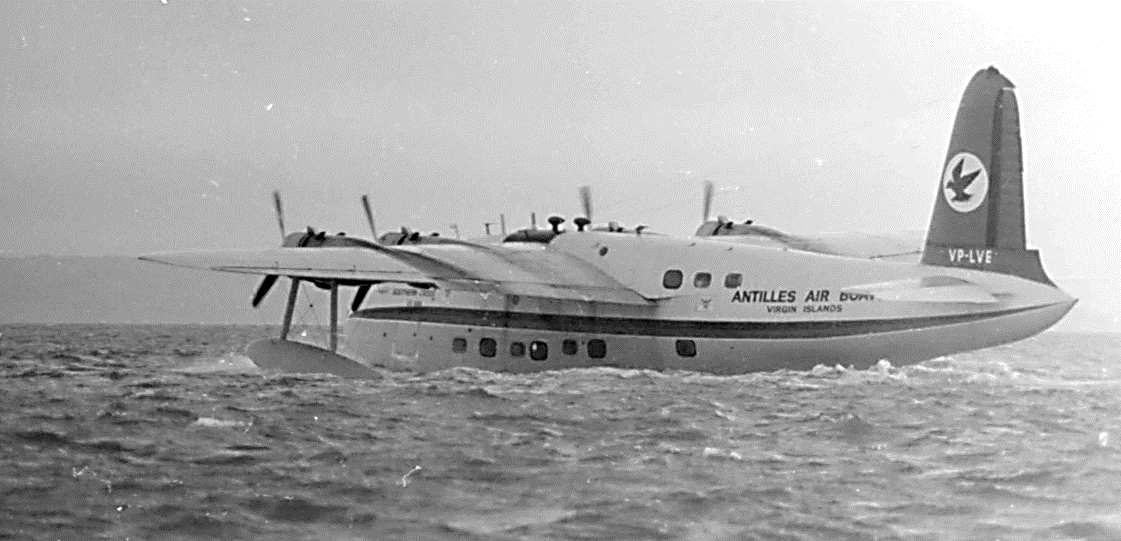

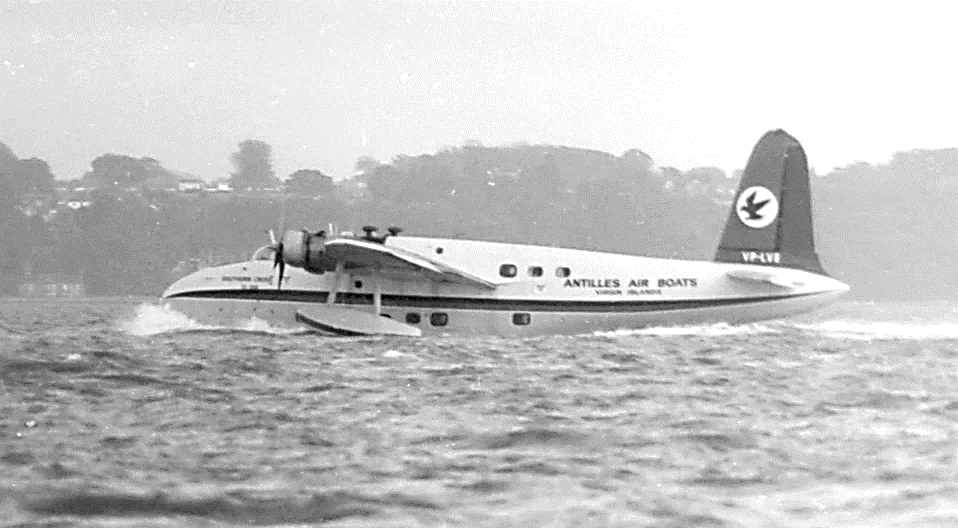

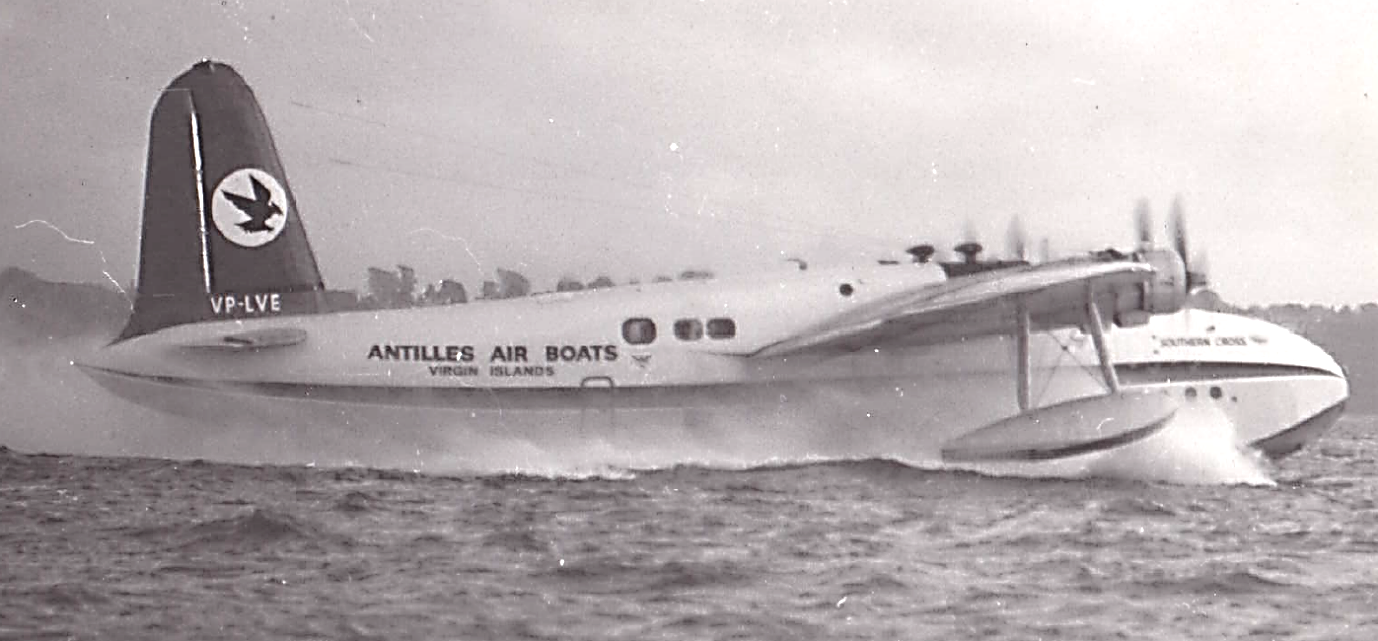

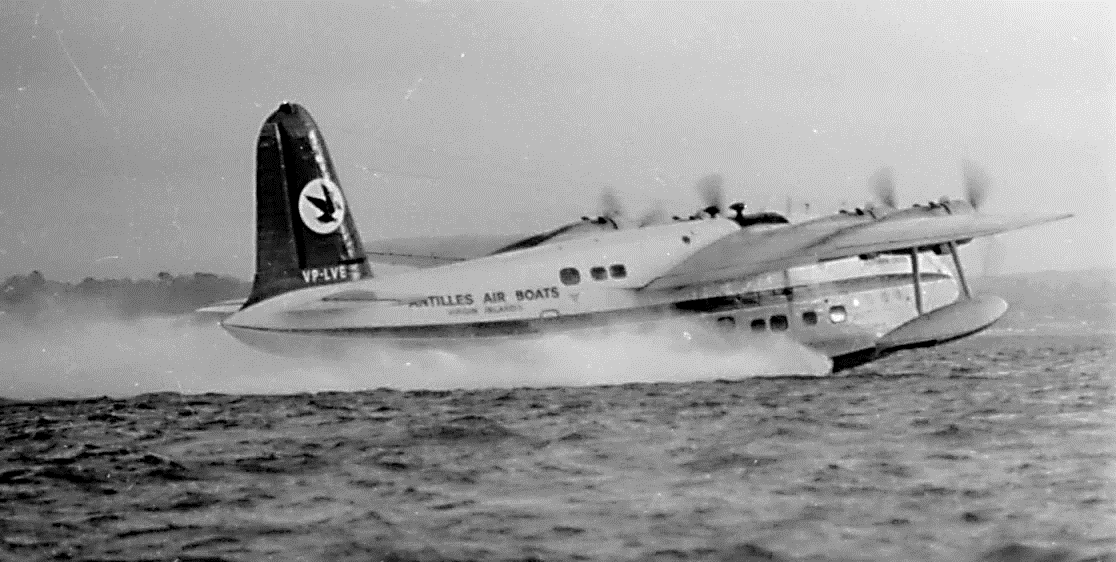

In 1977 I had the rare opportunity to fly on a flying boat reminiscent of times gone by. The boat was a 1943-built Short Sandringham named Southern Cross and registered as VP-LVE. It was operated by Antilles Air Boats. Both that year and the year before, it came all the way from St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands in the Caribbean to England to do some pleasure flights.

Preparations

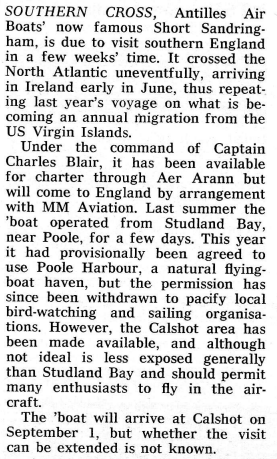

When I received the “week ending 27 August 1977” edition of Flight International, this article caught my attention:

In the classified advertisement section of that same issue there was more information:

Wow. How nice it would be to enjoy such a pleasure flight! Er, why not try it? I called a spotting mate to see if he would like to join me. The answer was yes, very much. My issue of Flight had arrived on Saturday, August 27. The flights would start on Thursday, September 1, so I knew I had to be quick. I lived in the Netherlands, not England, so this meant I had some organizing to do.

On Tuesday, I called the Dorset number, or rather, I had a post office do that for me. It was the first time I made an international call, and, how could I know what the Blandford Dorset telephone code was? (The internet did not exist at the time, let alone Google.) The guy on the phone – I think he worked for, or even was, M.M. Aviation – said he had seats available for Monday afternoon, September 5, around 2:00 pm and we should report in Calshot on time. With that confirmation in the pocket, we arranged train tickets from Amsterdam to Southampton.

Late on Sunday, September 4, I left home, joined my pal and rode the train to Hoek van Holland to catch the night ferry from Hoek to Harwich. In London, we transferred from Liverpool Street station to Waterloo station by Tube (metro). In Southampton, we took a bus through the New Forest to Calshot village, arriving about 1:00 pm. There, we saw the Sandringham in the distance, between trees, floating in the water between the English coast and the Isle of Wight.

Next, we walked over to Calshot pier, the former RAF flying boat base, but found it deserted. However, soon after, a bus appeared full of air enthusiasts and the MM representative. Unbeknownst to us, they had assembled at a meeting point in Southampton. The representative was happy to see us, fearing we had not made it.

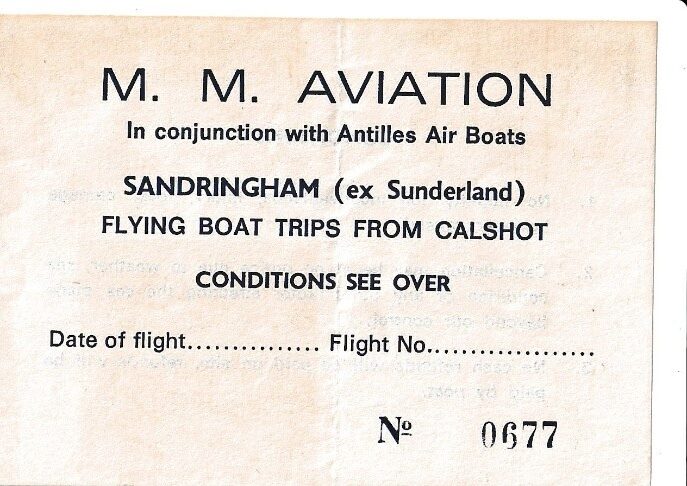

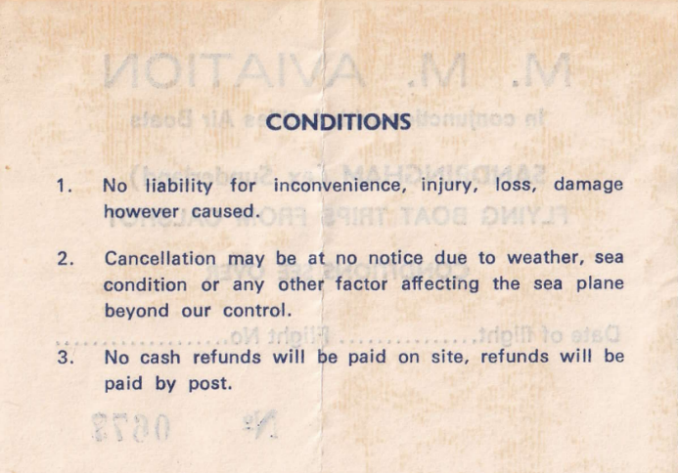

The airplane had arrived from Ireland on Friday around 17:30 pm. There were no flights over the weekend. Our flight was the first one on Monday afternoon. In the morning, there had been a flight for the press and other invitees. During that week, there were 17 flights in total, the last of which was on Friday, September 9. (On Tuesday, September 6, flights had to be cancelled because of low clouds.) Although Antilles Air Boats (AAB) was the operator, the boat was leased by Aer Arann, a small Irish airline normally flying between Galway, Ireland, and the three offshore Arann Islands. The ticket – or was it the boarding pass – mentioned “M. M. Aviation in conjunction with Antilles Air Boats” with no mention of Aer Arann. I assume their role was limited to some aeropolitical aspects while M.M. Aviation took care of local arrangements, sales and promotion. The fare was ₤19.50. According to the Bank of England, in 2024 this equals ₤112, or $143. Not only was this very cheap for a one-hour sightseeing flight, but when considering its unique and historical nature, it was a true bargain.

The Boat

A launch took us to the flying boat, which was moored quite a distance away. Calshot pier borders on Southampton Water, but for environmental reasons no permission had been obtained to use that. Rather, a stretch of water on the Solent abeam the Beaulieu river mouth (off Lepe) had been assigned.

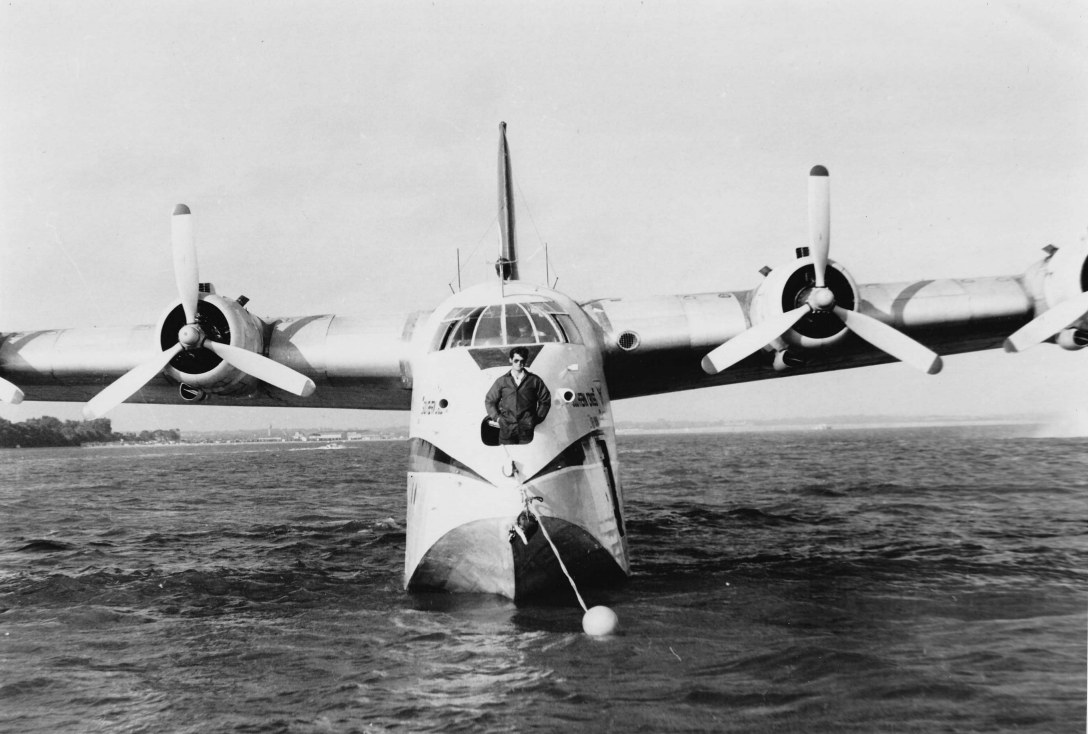

We approached the boat from the rear and took our first pictures.

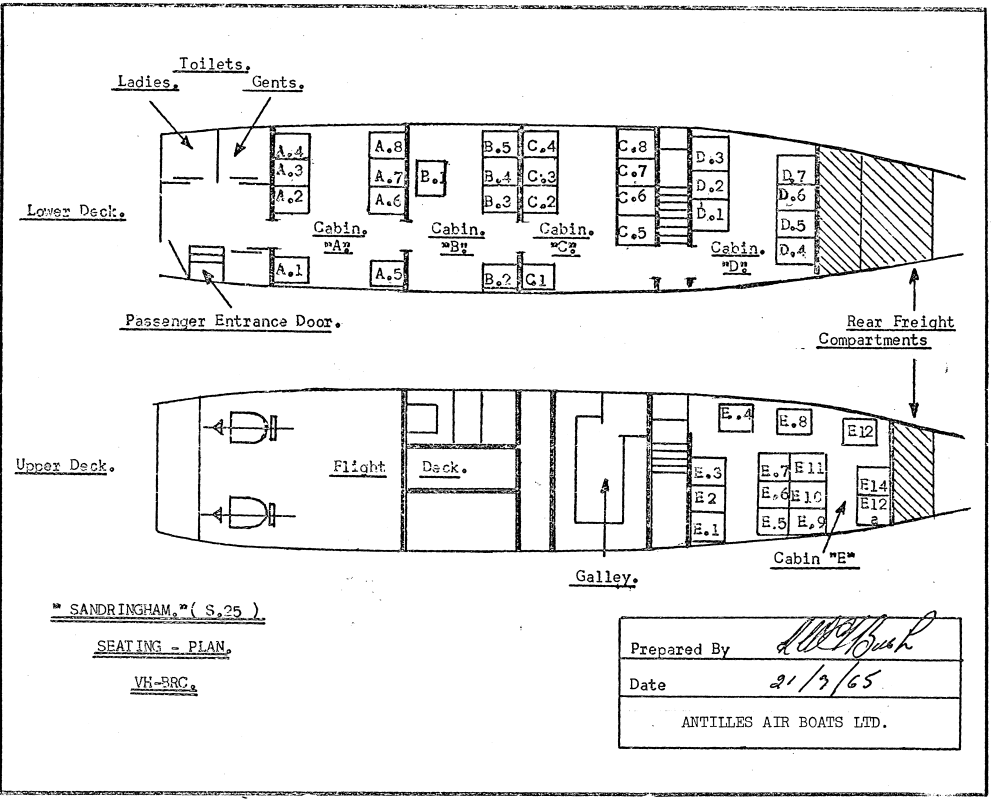

Next, we moored at the entrance left forward. Negotiating two steps down, we entered a vestibule area with access to the bow area, left, and the passenger compartments on the right. While this area was unfurnished, exposing the metal skin of the boat, the cabins were furnished with wood, reminding us that this airplane was built before plastics had invaded aircraft interiors. The seating arrangements were very unlike the modern jet tubes with its seats lined up as a military regiment. The main deck had four compartments, each seating six or eight in a club layout, for a total of 30.

Between the third and fourth compartment, there was a steep set of stairs, 59 cm (23 inches) wide, leading to the upper deck. At its top, to the left (so, forward in the direction of flight) was the galley. To the right there was another passenger compartment, seating 14.

The cabin diagram below, although taken from the AAB manual, was drawn by Ansett in 1965 for VH-BRC as the boat was then known. It shows the two decks, the five passenger compartments, the galley and the flight deck. Note the gender-specific toilets opposite the entrance door. Today, the boat is preserved in Southampton’s Solent Sky Museum. When I inspected the boat in December 2024, three more aft-facing seats were present in cabin B. It is likely that they were there in 1977 as well. I assume Ansett also had them, but did not show them as they were for the crew and not to be booked. In cabin D, there was one fewer forward-facing seat than Ansett showed.

Seating was open, but after 47+ years, we do not remember where we sat! The cabin and seat numbers were not marked in the boat.

During the cruise flight, we could freely roam around the two decks.

The cockpit, on the upper deck, was not accessible from the galley as the wing was in the way, although small items such as meals could be handed through. It could only be reached via a vertical set of steps in the vestibule area.

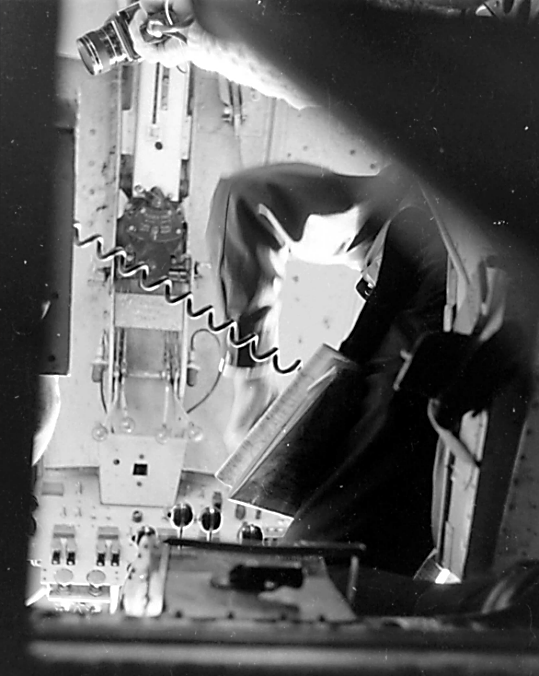

Taking turns, we were all allowed to climb the steps and take cockpit pictures in-flight. While waiting, I took a picture straight up. It shows the ceiling of the flight deck, the left arm of the co-pilot and a communications cord that is also visible in the next photograph, taken upstairs.

The captain was the famous Charles F. Blair Jr., founder and president of Antilles Air Boats and the third husband of the even more famous movie actress Maureen O’Hara.

Charles Blair was sadly to die one year later in an accident with a Grumman Goose. On the right sat Ronald Gillies, who had already flown the same airplane when it was still VH-BRC. Noel Hollë was the flight engineer and James C. (Jim) Flanagan, also a flight engineer, was the mooring man, or bow officer. Flanagan had greeted us from his prominent position in the bow when we arrived in the launch. At 29, he was by far the youngest member of the crew. He had only arrived the day before, and this was his first visit to the UK. According to documentation that was sent a few weeks later, Noreen Gillies, Ron’s wife, was the flight hostess. However, Maureen O’Hara was also on board, selling merchandise such as Sandringham T-shirts to the passengers after each flight.

The flight deck itself was roomy, with seats not only for the two pilots but also for a flight engineer. Unlike in landplanes, his position was at the far end of the cockpit, facing backward.

In 2024, and very likely in 1977 as well, three more seats were present that are not shown in Ansett’s diagram. A navigator’s station, a jumpseat and a seat, according to a museum volunteer, that had been installed for Maureen O’Hara.

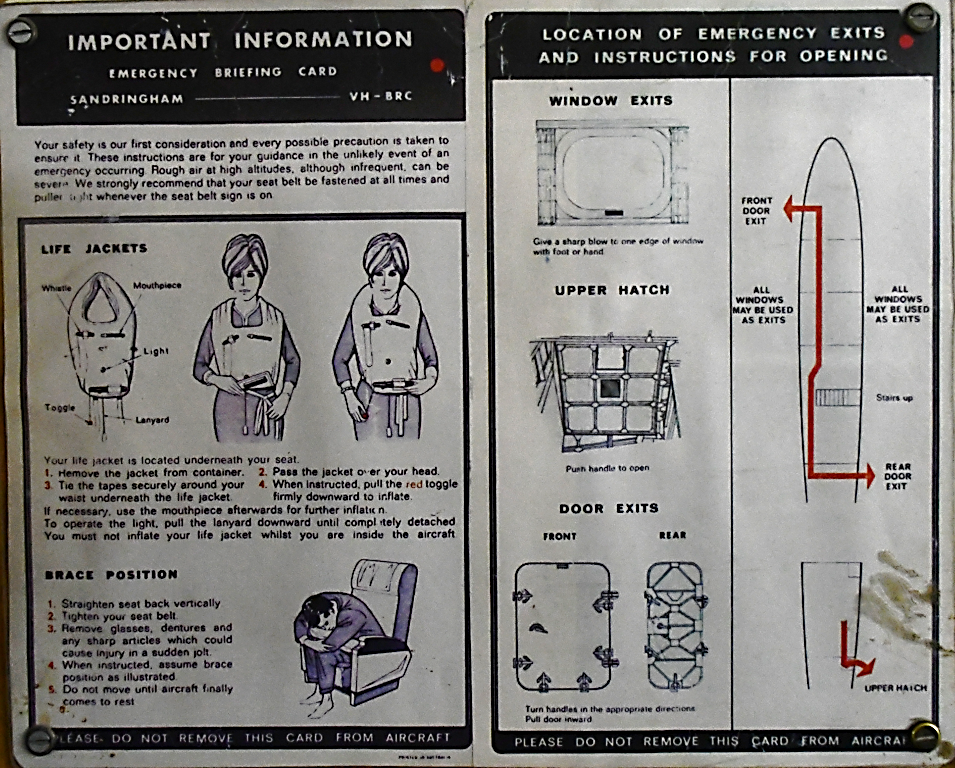

I do not remember if any safety briefing was given, but I doubt it. It is also unlikely there were safety cards for each passenger. There must have been cards posted in the compartments, as they were still there in 2024. They were for VH-BRC; AAB probably never made their own. For cabin E, the card was fixed above the stairs, not well in sight. In cabin D, it lacked altogether. Perhaps that one had been removed for or by an acquisitive collector?

The card shows the entrance door, on the left, a smaller hatch at the far right, plus an upper hatch, all as emergency exits. Both hatches were only accessible via the lower and upper cargo compartments, respectively, which, themselves, were accessible from the cabins. The card adds that “all windows may be used as exits.” On the lower frame of each cabin window was a sign saying:

Emergency exit – to eject window give a sharp blow towards one edge of window with foot or hand.

Above the portals between the compartments there were fasten seat belt – no smoking signs, very elongated as it used text, not symbols.

The Flight

Tension mounted as the door was closed, the launch left and the engines started. Charles Blair steered the boat into the wind and started the take-off. After a long run, with water splashing against the aft windows, it gently lifted off. The rate of climb was very low. We cruised at an altitude of not more than 500 feet (150 meters). I have no recollection of the route, but with its very modest cruising speed of about 120 knots (220 km/h), we possibly could have reached as far as Weymouth before returning. Or did we go to Bournemouth and then circle the Isle of Wight, as Trevor Bartlett reported was the case on his 6:51 pm flight that day? (see https://abpic.co.uk/pictures/view/1276125). Perhaps a “boomer” from south England or the Isle of Wight will recognize the scenery in these pictures.

After about one hour, we came back in for the landing on the Solent. Suddenly, water splashed against the windows again. Upon mooring, we saw a boat waiting with the next group of enthusiasts and an empty boat waiting to pick us up.

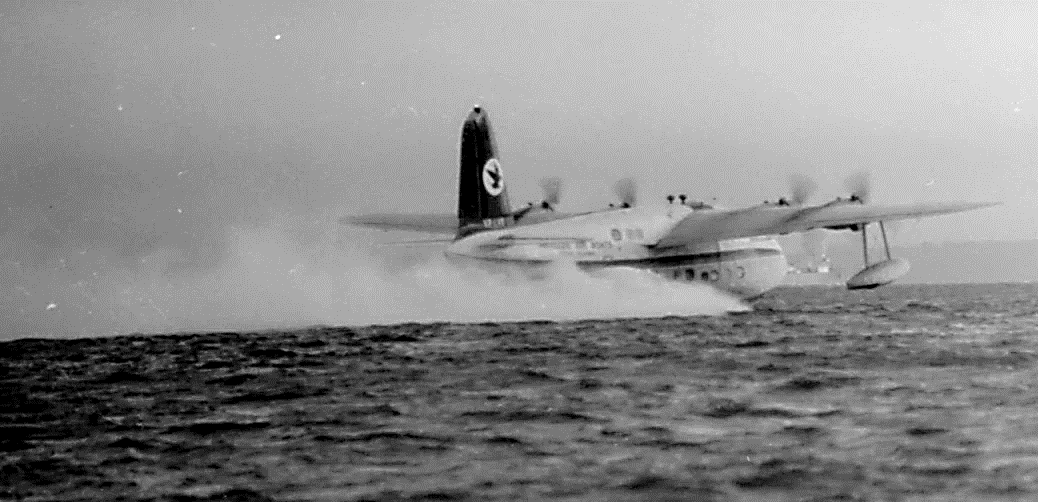

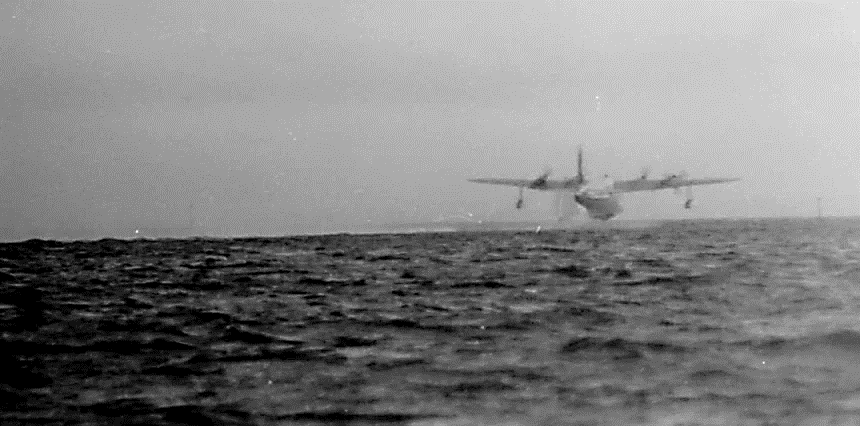

Before returning to Calshot, we floated at a safe distance for taking pictures of Southern Cross taxiing and taking off on its next flight.

The press release for the September flights had announced that “Flying in Southern Cross recaptures something of the space and grace (and indeed the pace) of a near-forgotten era of civil aviation.” After 47 years, these words have only gained in significance.

Museum Piece

Southern Cross returned to Calshot in 1981. It did not do pleasure flights anymore, but was stored there. Later, it was taxied on its two inner engines across Southampton Water to Lee-on-Solent before being pontooned to Southampton. Since 1984, it has been by far the largest artifact in the local Solent Sky Museum. It has been repainted in the colours of Ansett Airlines, displaying the registration VH-BRC and bearing the name Beachcomber. While it had an impressive active life of almost 40 years, its passive, museum life has now surpassed that in years.

Registration mark

Why did the boat have that odd registration mark – VP-LVE? AAB was based in the U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI), which follows U.S. aviation regulations. When Blair collected the boat in 1974 in Australia, he registered it as N158C. But the U.S. authorities would not allow him to use the N register for sustained operations with passengers. Across from the USVI, at a stone’s throw from St. John, was the island of Tortola, a regular AAB destination. This belonged to the British Virgin Islands (BVI). At the time, it issued registration marks in the VP-LVx range. Next in line was VP-LVE, which the BVI governor was happy to grant. The Director of Civil Aviation for BVI (as well as other British leeward and windward islands) well recognised the Sandringham’s certification, so that VP-LVE could be issued a Certificate of Airworthiness and could fly us, passengers.

Sources

To fill the gaps in my memory and for additional information, I consulted:

- Rob Hemelrijk, who had joined me that day;

- Letter by Dersot Doran, dated 20 September 1977

- Fabulous Flying Boats, by Leslie Dawson, 2013

- antillesairboats.com

All black and-white photos, and the three exterior colour photos, were taken in 1977. Except for these three, all photos by the author.

Fons Schaefers: f.schaefers@planet.nl, January 2025

Tags: avgeek, Charles Blair, flying boat, Maureen O'Hara, Sandringham, Short Sandringham, Southern Cross

Trackback from your site.