The Boeing B-314 Flying Boat

Written by Robert G. Waldvogel

Seeking to inaugurate transatlantic scheduled service from New York to complement its existing Martin M-130 Pacific routes from San Francisco (Alameda) to Hong Kong via Manila, Pan American Airways submitted a proposal for a long-range, four-engine, transoceanic flying boat. It would be capable of carrying a 10,000-pound payload on at least 2,400 statute mile routes against a 30-mph headwind at 150-mph. The proposals went to Boeing, Consolidated, Douglas, and Sikorsky. This was in February of 1936. As Andre A. Priester, its chief engineer, pointed out, “Flying boats carried their own airports on their bottom.”

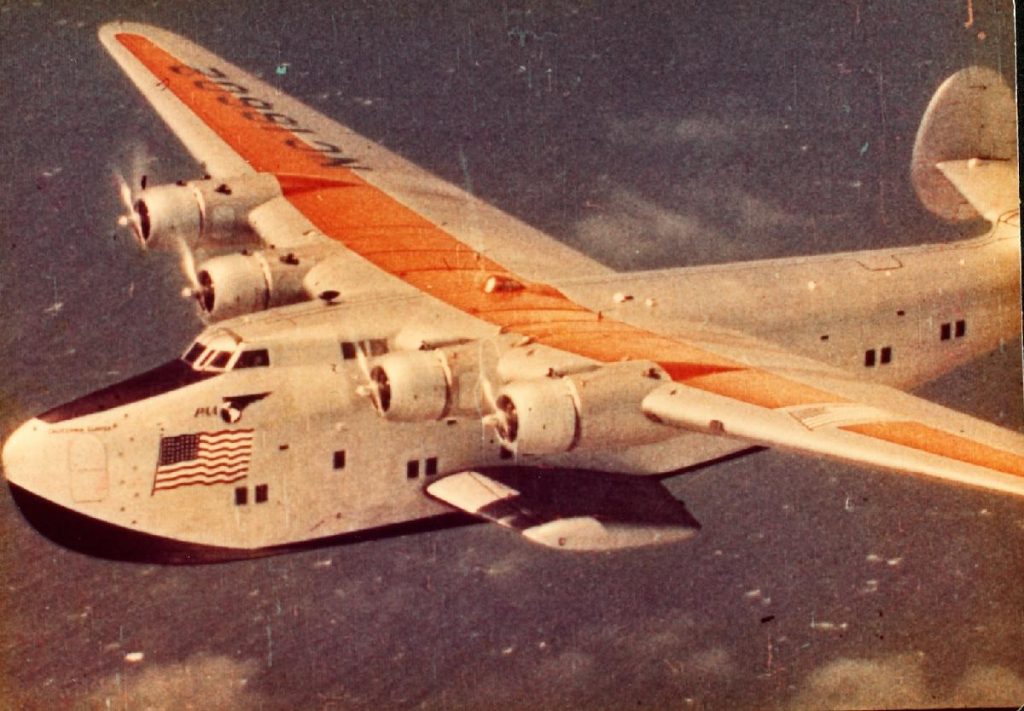

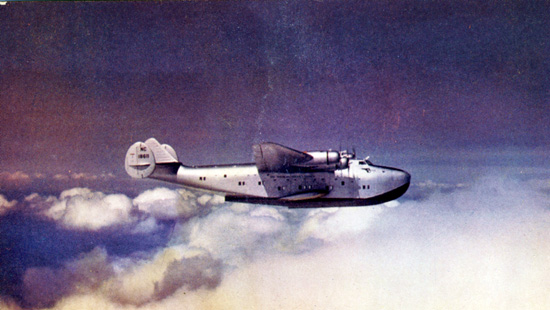

The ultimately selected Boeing B-314 was a true, aerial ocean liner that was both efficient and elegant, and in a class of its own.

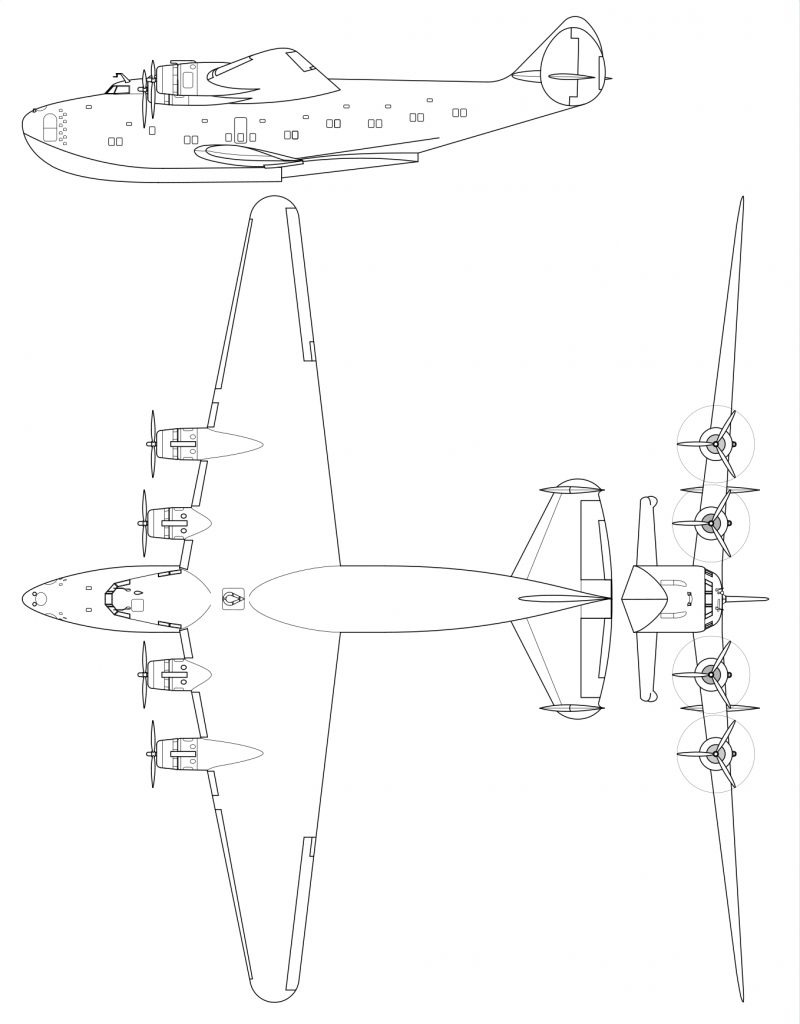

Befitting a mixed-mode vehicle, it employed ship construction techniques with a compartmented double bottom and full-depth, forward and aft, watertight bulkheads, producing a 106-foot overall length. The massive, three-section, high-mounted wing, which spanned 152 feet, was subdivided into a center, hull-integral section that extended beyond either side’s inner engine nacelles, and two outer, watertight sections. Its center wing spar, supported by the upper fuselage, featured both increased strength and internal volume, while its 4,200-gallon fuel capacity was distributed between wing center section and lower-fuselage extending “sponson” tanks. Appearing like mini-wings, these sponsons provided lateral, in-water stability, obviating the need for traditional floats, and alternatively served as passenger entry platforms leading to the cabin door. So cavernous were the main wings, that they contained interior catwalks to permit in-flight inspection and maintenance of both their structure and the state of the engines.

Powered by four, 14-cylinder, 1,500-hp Wright Cyclone R-2600-A2 piston engines housed in 69-inch-diameter nacelles and driving three-bladed, 14.9-foot-diameter, fully feathering Hamilton Standard propellers, the Boeing B-314 had an 82,500-pound maximum takeoff weight and a 23,500-pound payload capacity. Its service ceiling was 21,000 feet.

Subdivided into two decks, the flying boat featured a carpeted and upholstered-chair upper level stretching more than six feet in height and extending 21 feet in length. It was provision

ed with pilot, copilot, navigator, and radio operator cockpit positions; a master’s desk; a meteorologist’s station; crew sleeping bunks; and a baggage compartment which was partially located in the wing. Cockpit and cabin crew consisted of between 10 and 16 members. A starboard-positioned stairway provided inter-deck connection.

The sound-proofed cabin, itself subdivided, featured five, ten-passenger compartments; a single, special, four-passenger section; a deluxe bridal suite; a dining room; a full-service galley; a men’s restroom; and a ladies’ powder room. Passenger capacity ranged from 74 by day to 34 by night, in convertible berths.

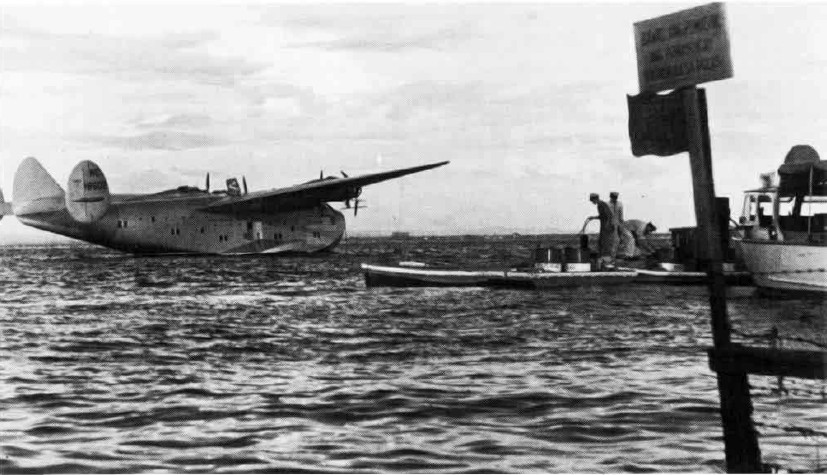

Amid the blare of a brass band and a quay thronged with friends, relatives, messengers, reporters, and photographers, the first 22 passengers, having had their tickets, passports, and baggage checked (the latter restricted to a 15-pound maximum), filed down the long dock to which the B-314, immersed in Port Washington, Long Island’s, Manhasset Bay, was moored. The date was June 28, 1939, and the plane they boarded was the most mammoth and luxurious American airliner yet built, one that both internally and externally reflected the nautical heritage which had inspired it.

Piloted by Captain Rod Sullivan, who had previously operated the inaugural flight to Wake Island in the Pacific on the Sikorsky S-42, the transatlantic B-314 “Dixie Clipper” inched away from the dock at 1500 hours, local time.

Lumbering through Manhasset Bay, it executed its acceleration run, cascading water being pushed up behind it. Moving up “on step,” it disengaged itself from the surface, and the North American continent, leaving both behind at a 120-mph airspeed. When a post-departure engine check revealed good readings, the throttles were pulled back from the 1,550 to the 1,200-hp level, thresholding an initial climb to 750 feet, and then a secondary power reduction, to 900 hp, for a final ascent to altitude at 126 mph.

Aerially connecting the North American and European continents, the “Dixie Clipper” alighted in Horta, the Azores, and Lisbon, Portugal, before terminating in Marseilles, France, the following day after a flawless execution of the southern transatlantic route.

“Yankee Clipper” operated the first northern one on July 8 with 17 passengers. Fares were $375.00 one-way and $675.00 round trip.

According to Pan American’s June 24, 1939 timetable, the once-weekly, 3,411-mile northern crossing, operating as Fight 100, departed Port Washington at 0730, arriving in Shediac, New Brunswick, at 1230. An hour later, it took off for Botwood, Newfoundland, alighting at 1630, before redeparting at 1800 for the oceanic portion of the journey, touching down in Foynes, Ireland, at 0830 the following day and once again becoming airborne at 0930. It reached its Southampton destination at 1300. The return, Flight 101 left two days later, at 1400, and arrived in Port Washington, also at 1400, the day after that.

The longer, 4,251-mile southern route, operated under flight number 120, departed at 1200, transited Horta, the Azores and Lisbon, and arrived in Marseilles at 1500, two days after it left Long Island. The return, as Flight 121, departed at 0800 and touched down in Port Washington at 0700, also two days later.

World War II proved to be Port Washington’s enemy as a center of civil flying boat activity. Hostilities initially necessitated northern and southern route terminations in, respectively, Foynes and Lisbon, before the former was altogether discontinued on October 3, 1939, the last Manhasset Bay operations occurring with “Dixie Clipper,” “Yankee Clipper,” and “American Clipper” on March 28 of the following year.

Although Pan American ultimately transferred its Atlantic operations to North Beach (later La Guardia) Airport, longer-range landplanes, particularly in the form of Boeing’s own B-377 Stratocruiser, Douglas’s DC-6 and DC-7, and Lockheed’s Constellation, along with more suitable, paved runways, quickly eliminated the need for waterborne aircraft capabilities.

Brief though it was, the flying boat era constituted a glorious period of commercial aviation.

Trackback from your site.

Jerry Goodman

| #

Can anyone help with the routing of BOAC Clipper BERWICK (ex PanAm) traveling from the UK to Baltimore in March 1945 ? I’m trying to establish the start point and routing / stop overs my father (in SOE) would have taken on his journey at that time.

Thanks, in advance.

Reply

Howard Butcher

| #

## Comment SPAM Protection: Shield Security marked this comment as “Pending Moderation”. Reason: Failed AntiBot Verification ##

Tis a shame all the glitz and glamour have been gone from the airlines, possibly the last being the Concorde. The Flying Boat era was unique. Growing up, I was fortunate enough to fly on

the Sikorski VS-44A and experience several water take-offs and landings in So. California. A far cry from flying the Pacific or Atlantic. None of the B-314s survive except at the bottom of the

ocean (2), so the VS -44A is the only US built passenger flying boat in existence, sad to say.

Reply

Bruce Scottow

| #

Just amazing to read about this. To think of so many passengers, flying in such luxury and speed across the Atlantic – just 12 years after Lindbergh’s solo flight. And to think that most passengers on board were born before the Wright Brothers first flight in 1903!

Reply

Robert Waldvogel

| #

Yest, while speed and technological advancement have certainly marked aviation as the decades have unfolded, I doubt we will ever approach the luxury and elegance of passenger flying that aircraft such as the Boeing B-314 Flying Boat offered. I would love to have experienced it, but it was way before my time!

Reply