airline seat designations

Seat 21J: A Century of Airline Seat Designations – Part 1 (1919-1960)

By Fons Schaefers

Introduction

Anyone who flies regularly as a passenger, even when not necessarily keen on selecting his or her seat of preference, still has an idea of how airliner seats are identified. Seat rows are numbered from front to rear. Across each row, seats are given a letter. Thus, when the boarding pass says seat 21J, the passenger knows not to go and look in the forward section of the airplane but somewhere in the middle. And that it is on the right-hand side. At least, when seen in the direction of flight, because when boarding through a forward door, and walking down the aisle (or one of two aisles, as the case may be), this seat is actually on the left.

This way of identifying airliner seats is universal. But has it always been so? And if not, when was it introduced, and how were seats identified before? Let’s have a look at the history of airliner seat numbering. This article is about the period from the start of air transport to when the current system became common, around 1960. In the next part, I will focus on the years since then.

Pioneers

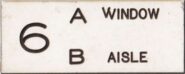

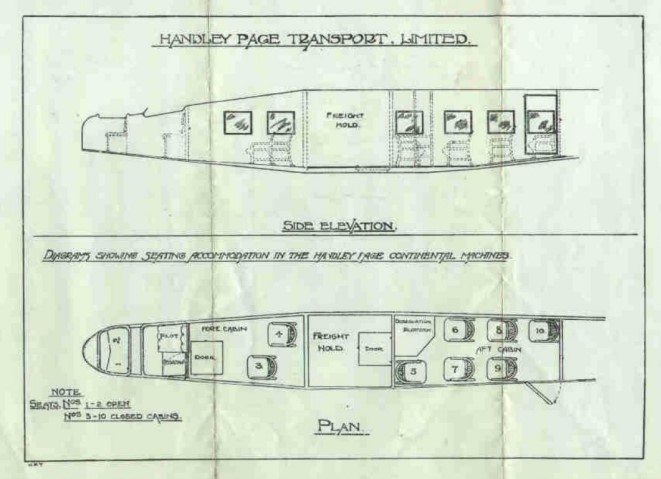

The very first instance of seat numbering likely dates back to the first year of air passenger transport in Europe, or to be more precise: in the United Kingdom in 1919. The Great War was just over and bombers made by the British aircraft manufacturer Handley Page were converted for passenger use. The company started an airline, named it Handley Page Transport Ltd., and offered flights from London Cricklewood across the Channel to Paris Le Bourget and Brussels-Evere, three times each per week. A single-sheet timetable describes the aircraft as “giant,” having the capacity to carry 12 passengers including the pilot and a mechanic. On the reverse side is a seating layout. Of the 10 passenger seats, two were at the front ahead of the cockpit and in the open air, two more were in a closed cabin behind the cockpit, and the remaining six were in an aft cabin, separated from the forward cabin by a freight hold.”The seats were numbered 1 to 10 from front to rear, left to right.

How passengers boarded is not directly clear. As with all period aircraft, it was a tail-dragger. On the ground, the aft cabin was close to the ground but the nose stood up high. The door in the aft cabin required only minor steps. The forward cabin and the open-air seats were inaccessible from the aft cabin and required boarding from outside. Likely, a tall ladder was used and only athletic passengers were allocated to these seats. In the forward closed-cabin, the plan marks a “door,” which I believe was in the fuselage bottom, accessible by the ladder.

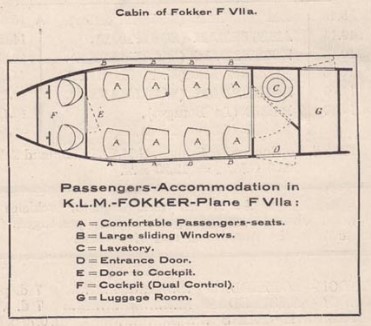

This early way of assigning numbers to seats was exceptional. Other airlines in the pioneering decade did not use seat numbers. I reproduce a cabin chart for the popular Fokker F VIIa as used by KLM in the mid-1920s. All eight passenger seats are identified as “A = Comfortable Passenger-seats.” There is no sign of seat numbering.

1930s

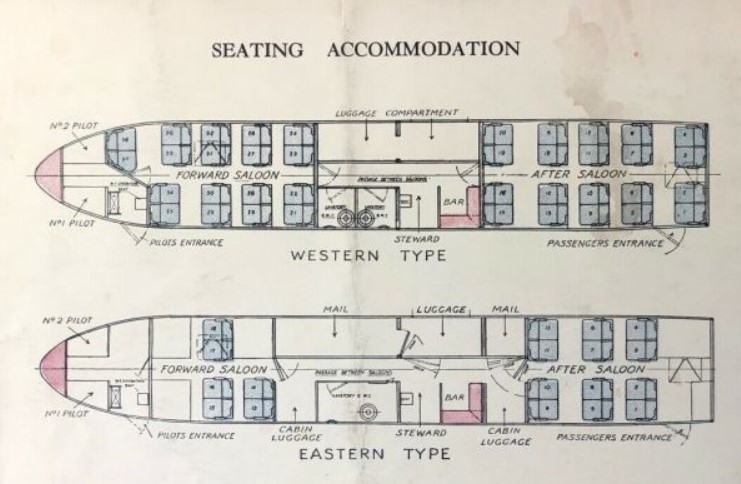

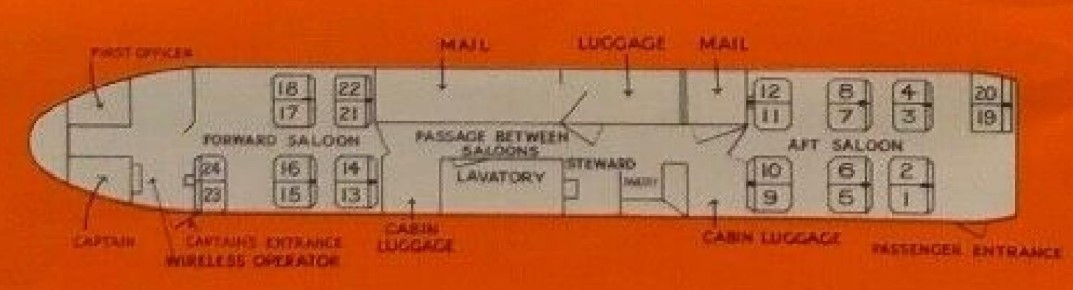

ln Great Britain in 1924, Imperial Airways was formed by a merger of Handley Page Transport and three other airlines. Handley Page continued building airplanes. In 1931, the Handley Page H.P.42 was introduced. Imperial used it in two versions, called the Western type and the Eastern type. The former was operated on the shorter routes in Europe (mostly London Croydon-Paris Le Bourget). The Eastern type was used on longer routes, such as from Cairo, Egypt to Karachi in what was then British India. Their seating capacities differed significantly: 38 on the Western type and only 18 on the Eastern type. In either variant, the passenger entrance door was at the extreme rear, on the left, and the seat numbering started there: left to right, rear to front.

At a later stage, the capacity of the Eastern type was increased with three double seats. These were placed at various locations across the cabin, but the original numbering was not changed. The result was that the additional seats were numbered out of sequence, creating a seemingly haphazard numbering pattern.

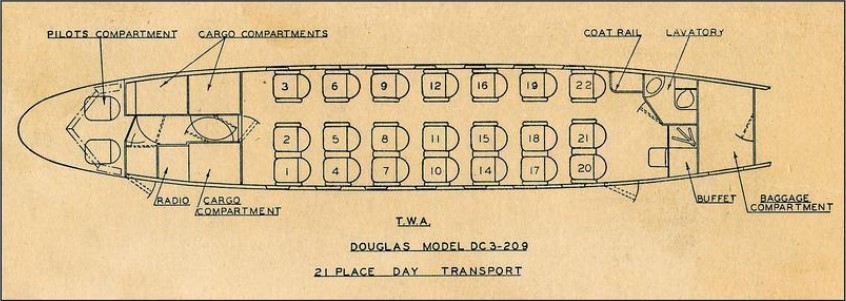

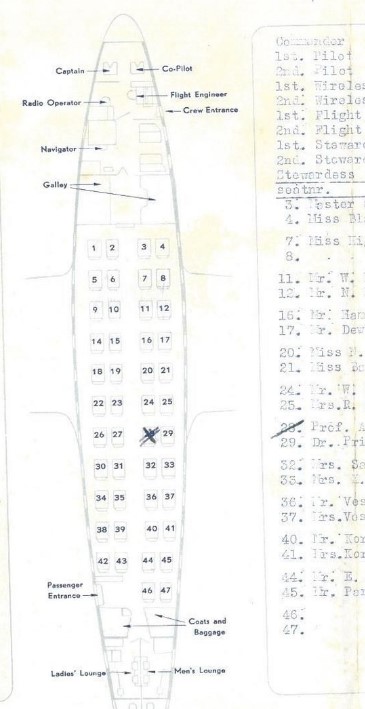

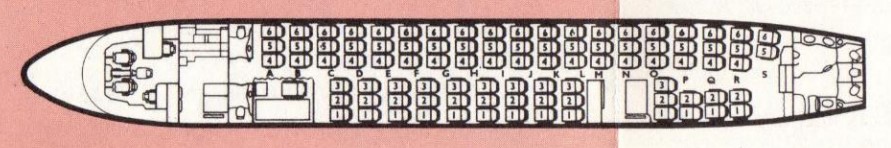

Later in the decade, when air transport in the USA had taken off and surpassed in volume that of Europe, the Douglas DC-3 was the aircraft type in use by the main airlines. Transcontinental & Western Airlines (TWA) was one of them. Their operations at the time were confined to the United States. Only after the war would it become an intercontinental airline and change its name to Trans World Airways). TWA published the seating layout shown below. Seats were sequentially numbered from left to right, front to rear. Number 13 was omitted, as it is regarded in Western culture as the “unlucky” number.

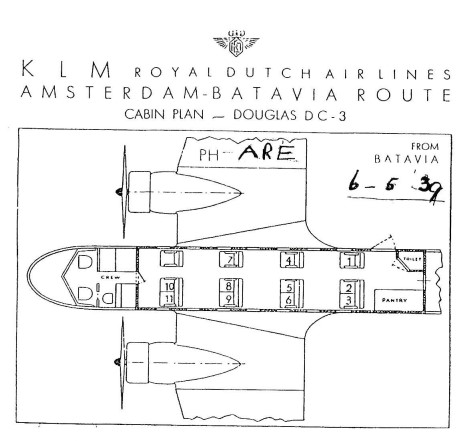

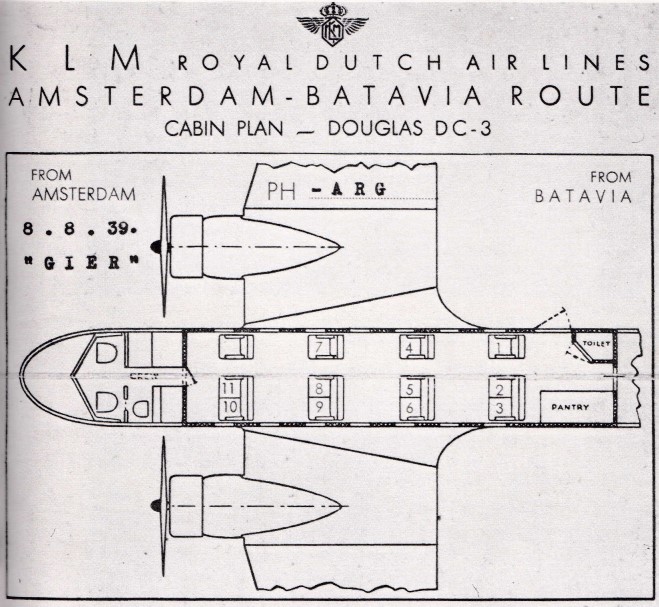

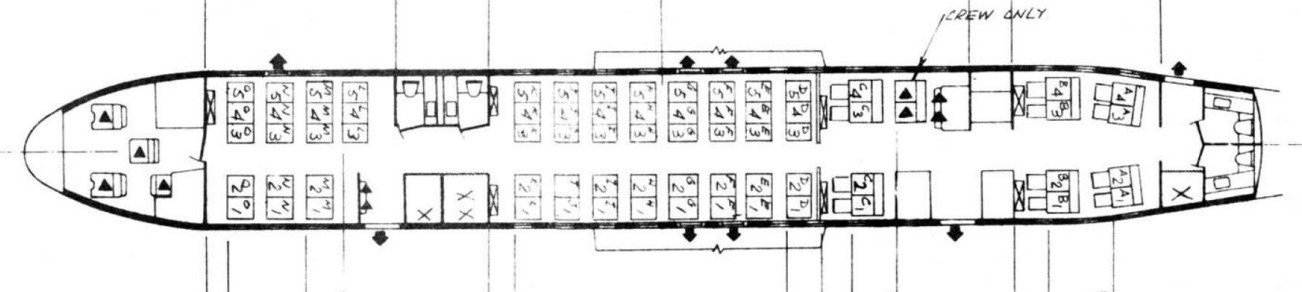

KLM Royal Dutch Airlines operated the DC-3 on what was then the longest air route, between Amsterdam, the Netherlands and Batavia, Netherlands East Indies (now Jakarta, Indonesia), taking five days and making 19 stops. Rather than fitting it with the normal DC-3 seating capacity of 21, only 12 seats were installed as seen in the below seat plans. One of these was non-saleable as it was for the steward. This was always a male, as KLM scheduled its stewardesses on the European routes only. The remaining 11 seats were numbered radiating from the passenger entrance door (located aft on the right side), so from right to left, and rear to front. Seating diagrams together with passenger names and their destination were made up for each flight and distributed to all on board. Current privacy rules and ethics did not exist then. I reproduce two plans, without the list of names. The first is for the flight starting in Batavia on May 6, 1939, and the second is for the flight departing Amsterdam on August 8, 1939. Note that in the latter the numbering sequence was reversed in the front row (seats 10 and 11). This may have been a typo, as the other plan did not have this anomaly.

The flight on August 8 would be one of the last on the route. With the outbreak of war in Europe a few weeks later, the route was initially truncated (starting at Naples instead of Amsterdam) and later terminated entirely.

Sequential numbering

While Douglas was the most successful manufacturer of airliners just before the war, Boeing tried to take its stake in the market with the Model 307, also known as the Stratoliner. It was unique in many respects: it was the first pressurized airliner and its cabin layout was asymmetrical, with four compartments seating six each on the right side, and a single row of nine seats on the left. Such a layout is reminiscent of European long-distance train coaches but has never since been repeated in air transport. Each of the compartments could be converted into sleeping mode, with four berths each: two upper and two lower. Even the airplane’s windows were asymmetrical, with two closely located windows per compartment on the right side and a more traditional lineup of nine windows on the left. Only 10 Stratoliners were built, five for TWA, three for Pan Am, and, a single ship for private use by Howard Hughes, then the owner of TWA. The prototype was lost early on and this delayed the entry into service which eventually took place in 1940. Within two years they went to war but most came back into civil service in 1945. TWA then used a more traditional cabin layout of 38 seats. Only one airframe, NC19903, survives, a former Pan Am aircraft preserved in flying condition at the National Air & Space Museum’s Udvar-Hazy Center adjacent to Washington-Dulles (IAD) airport. The hull of the Howard Hughes aircraft was converted years ago into a private houseboat and is now in the collection of the Florida Air Museum.

The unique cabin layout made for a unique way of seat numbers. I reproduce a cabin plan from a TWA ticket jacket, dating from about 1941. Left is forward. The numbering reflects the order of passenger comfort: the lowest numbers for compartment seats that could be converted into berths (1 to 17, with number 13 omitted), then the row of seats on the left (18-26), and finally the less popular middle seats in the four compartments (31-38). The first 16 numbers had the suffix U or L for upper or lower berth respectively. Note that in each compartment, the outboard seats were even-numbered and the inboard seats odd. The omission of the number 13 meant a reversal of the numbering direction in the fourth compartment.

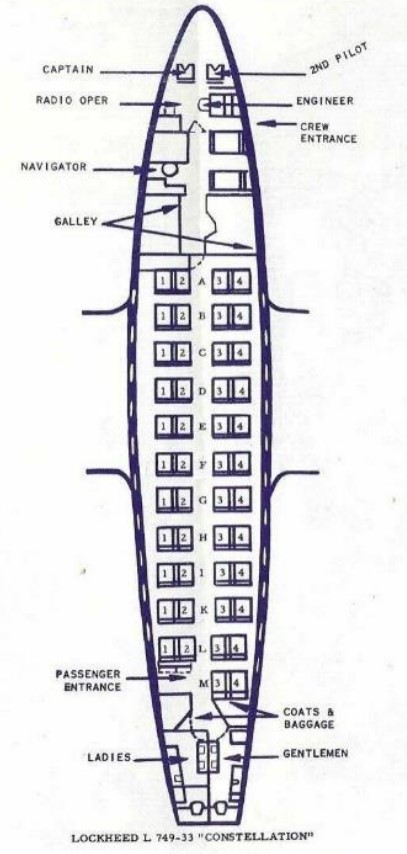

The practice of sequentially numbering all seats in airplane cabins continued after the war. In the second half of the 1940s, KLM used airplanes much larger than the DC-3, with seating capacities of up to 46. I show a Lockheed L-749 Constellation seat plan dating from a flight in September 1949. KLM still listed all the passenger names and destinations and distributed this to all on board.

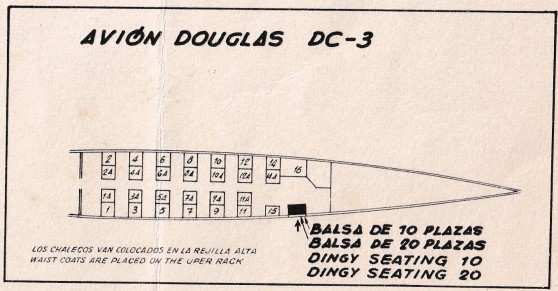

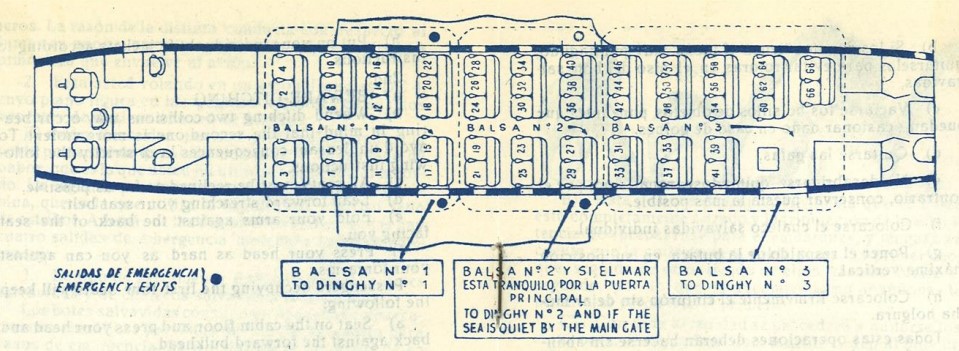

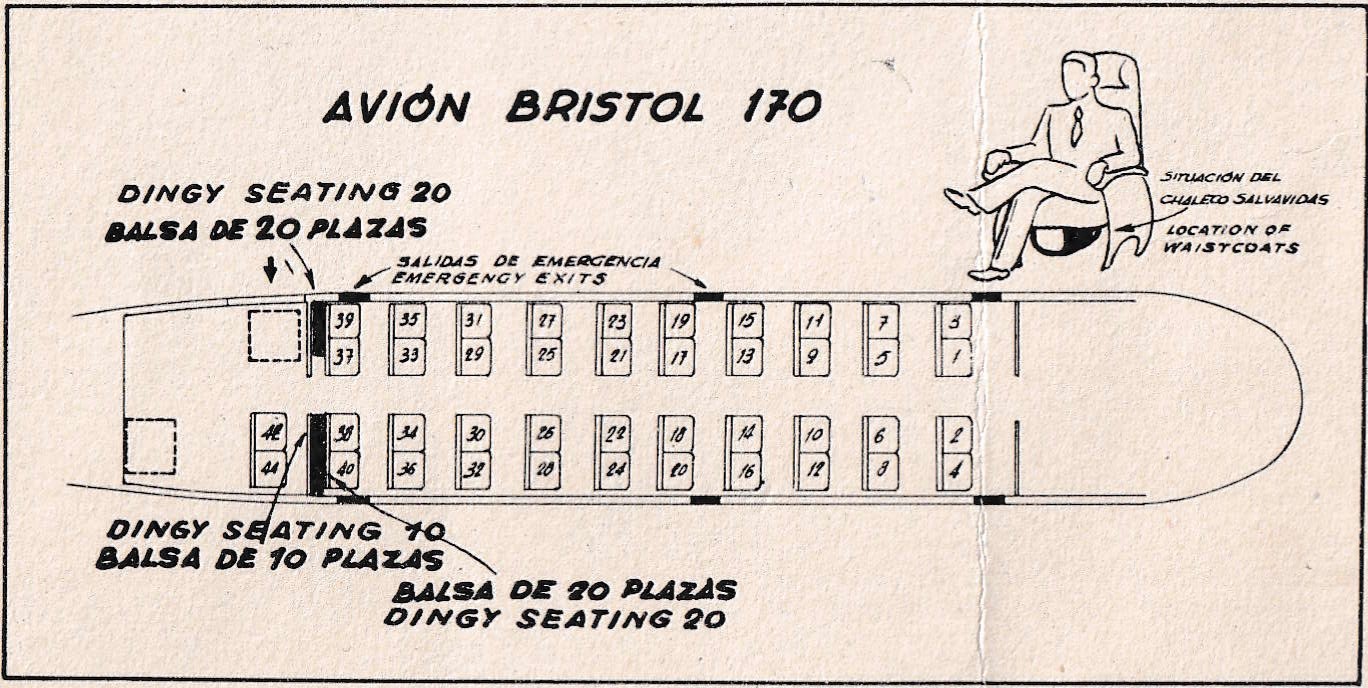

With so many seats, it became difficult for the crew to remember their numbers when directing passengers to their seats. Iberia thought of a way to make this easier. They came up with odd numbers on the left side and even numbers on the right side. This was for window seats. For aisle seats, an A was added. The number 13 was omitted. This diagram is taken from their safety leaflet and also shows the location of the life raft, or “dingy” as it was translated by Iberia.

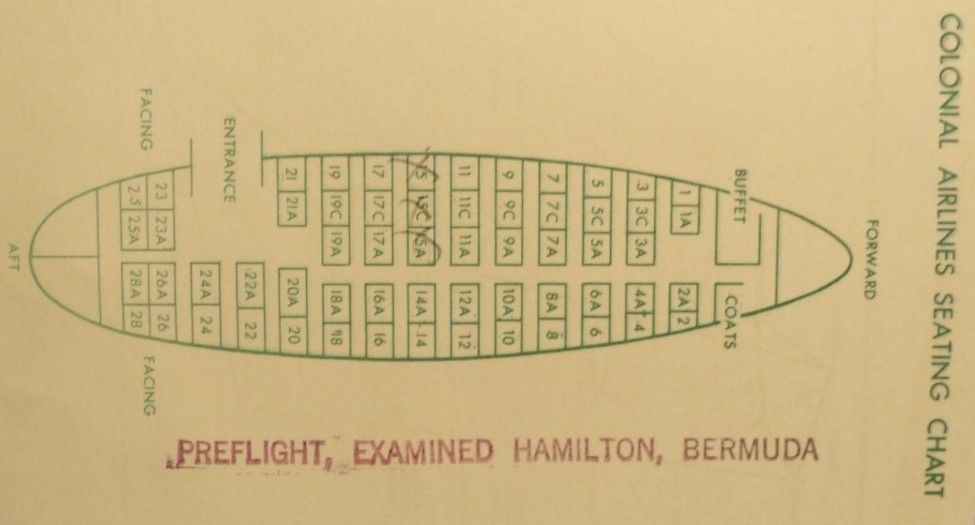

The same numbering method was employed by Colonial Airlines, a New York La Guardia-based airline that primarily flew between the Northeast USA and adjacent parts of Canada, but also had two overseas routes: from New York and Washington to Bermuda. On those routes, they used the DC-4, for which the seating chart is shown below. Being five abreast, center seats were added, marked with a C. You may wonder whether the illustrator actually saw the airplane or had an egg-inspired mental picture of how it looked like.

Iberia was apparently not entirely happy with their DC-3 numbering method. For the DC-4 they kept the left/odd and right/even style but discarded the letter A for the aisle seat and used numbers throughout. With more seats right of the aisle than left, this led to a situation where the numbers across the aisle progressively went out of sequence. As an example, the row with seats 39 and 41 on the left had seats 54, 56, and 58 on the right.

On their Bristol 170s, which were symmetrical in seating, this worked out better. The nose is right.

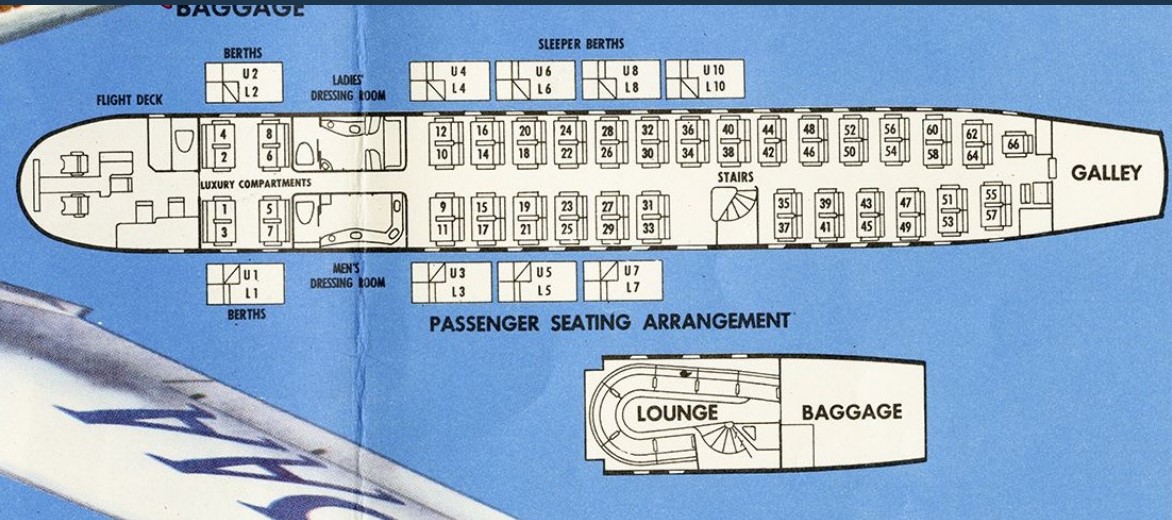

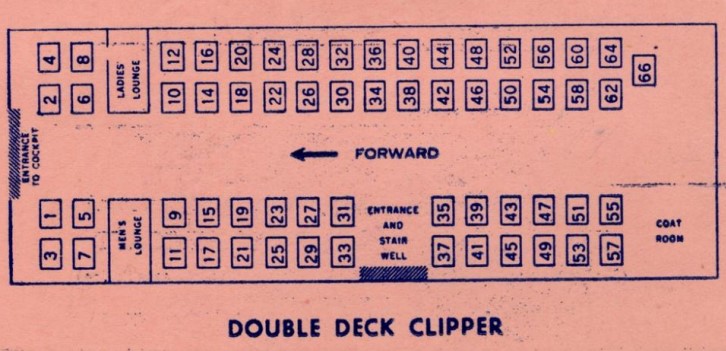

Pan American World Airways used the same method in their Boeing 377 Stratocruiser, which entered service in 1949. With equal numbers of seats on either side of the aisle, the numbering kept pace except for the aft section where there were no seats on the left in the boarding area. The layout also shows how the beds were numbered: U1 to U10 and L1 to L10. There was no U9 or L9.

On their boarding cards, Pan Am used a simplified presentation of the seat numbers, with a disproportionally wide aisle. “Double deck” referred to the lower deck lounge. This was not for use during take-off and landing, so its seats were not assigned and therefore remained unnumbered.

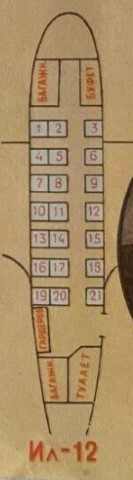

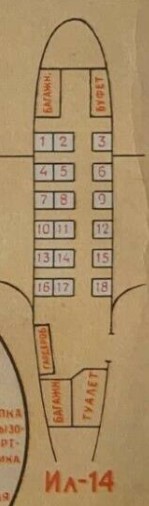

In the Soviet Union, Aeroflot applied the sequential numbering style on the Ilyushin Il-12 and Il-14. Note that the IL-12 has one more row than the IL-14, even though it is the smaller of the two types. The three-abreast layout shown here in a 1956 brochure was quite comfortable, as both types could seat up to 32 passengers in a four-abreast arrangement.

Aeroflot brochure extracts, 1956.

Compartment letters

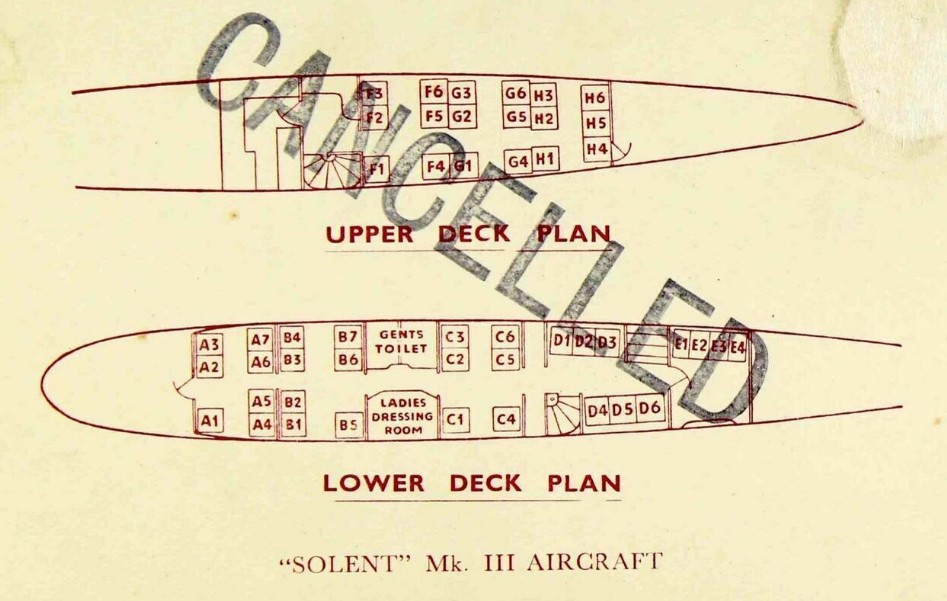

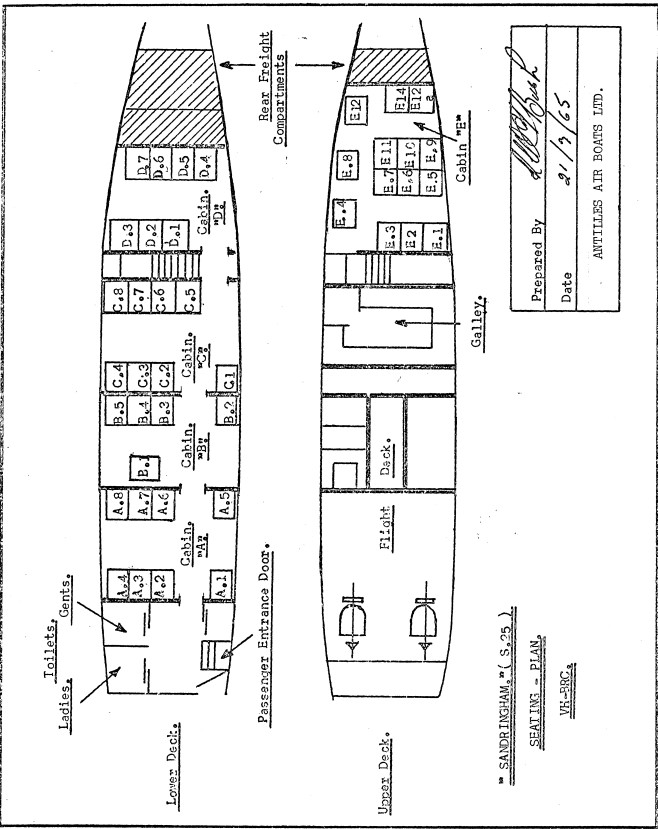

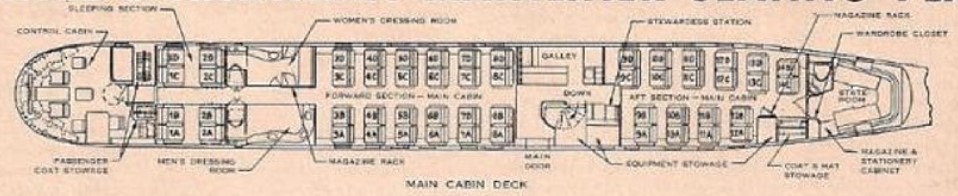

In the 1940s and 1950s, several air services were performed with flying boats, in most cases of the Short Brothers & Harland make, a Northern Ireland company. The design of the boats was such that it lent itself ideally to cabin compartments. I reproduce two samples: a Solent and a Sandringham.

The Solent was used by Aquila Airways in the 1950s between Southampton, Madeira, and the Canary Islands. It had eight compartments, identified from front to rear, main deck to upper deck as A to H. Within each compartment seats were numbered from left to right, front to rear. An exception was compartment D which had seats facing sideways and called for a different way of numbering.

In the 1950s Short Sandringhams, operated by TEAL of New Zealand and Australia’s Qantas, crossed the Tasman Sea between these two countries. Ansett Airlines used them to operate to such remote islands as Lord Howe Island. After many years, two of the Ansett’s went to Antilles Air Boats (AAB) of St Croix, US Virgin Islands. In 1976 and 1977, one came to England for some pleasure flights off Poole and Calshot, near Bournemouth and Southampton respectively (I was lucky enough to be on one of those). That Sandringham is now preserved in the Southampton Solent Sky Museum, in Ansett livery. There is a nice website with many details of the AAB operation (antillesairboats.com), including an Operations Manual (from which I copied the seating plan). It is dated 1965 so must have been drafted by Ansett, in spite of having AAB’s name on it. The seat numbering resembles Aquila’s: letters for compartments and numbers within each compartment. Note that there was a seat E.12a, but no E.13.

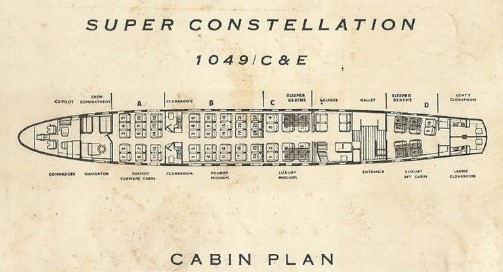

On land aircraft, compartments were also used and identified by letter for seat allocation purposes. An example is Air India, with its Lockheed Super Constellation, in service from 1954. Compartment identification started at the front. Within each compartment, numbers went from left to right, front to rear. Note that the economy class compartments were the first two (A and B), with the latter two (C and D) being first class with sleeper accommodation.

Class

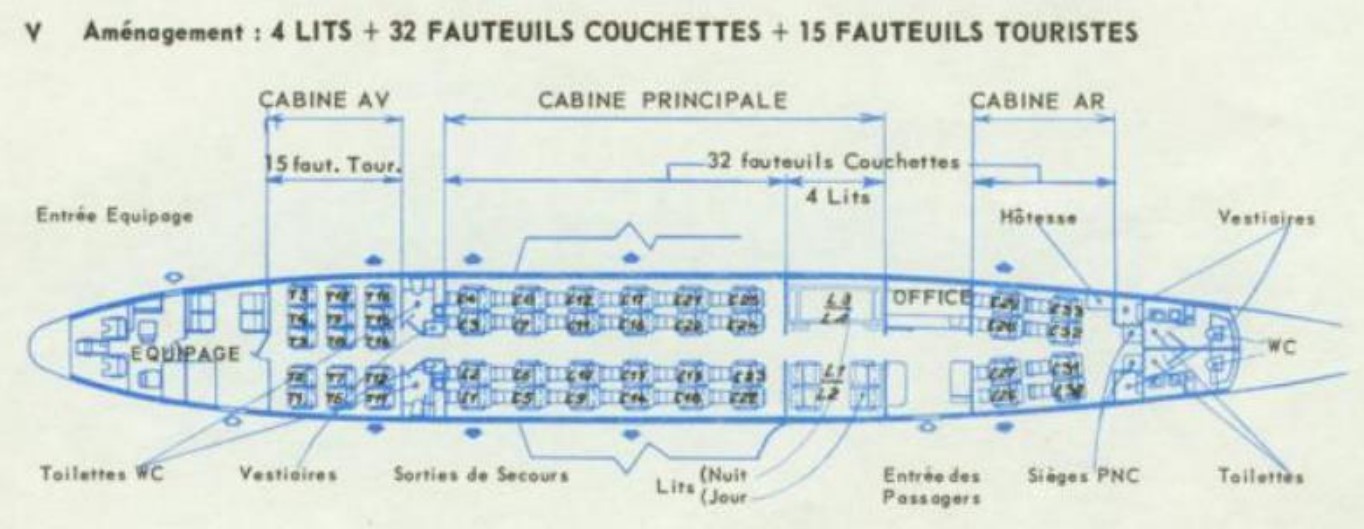

Another way of assigning compartments and seats was by class. On their Super Constellations, Air France employed a variety of layouts. I show the 15 tourist/32 couchette/4 beds layout.

The tourist class seats had the letter T followed by a number. Similarly, couchette seats and the beds started with a C and L (bed = lit in French), respectively. Couchettes were seats that reclined to allow sleeping but were not as comfortable as the beds.

Coordinates

So many different ways of designating seats must have been confusing. With capacities increasing, airlines needed a way to bring more structure to matters. The solution existed in the grid pattern that each and every cabin presented. It only needed people to recognize it. The typical grid layout of airplane cabins was that of multiple rows along the length of the cabin and seats lined up in each row. A simple system of coordinates solved the seat designation puzzle. Two solutions evolved:

- Longitudinally: rows assigned by letters; laterally: seats across assigned by numbers, or

- Longitudinally: rows assigned by numbers; laterally: seats across assigned by letters.

In both cases, a combination of letters and numbers. This is generally known as an alphanumeric presentation. While this describes well the first solution, I propose using a new word for the second solution to distinguish it from the first and reflect the order of numbers before letters: “numeric-alpha.”

Alphanumeric

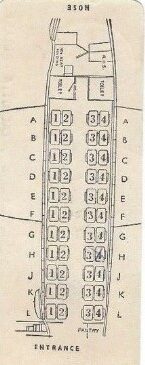

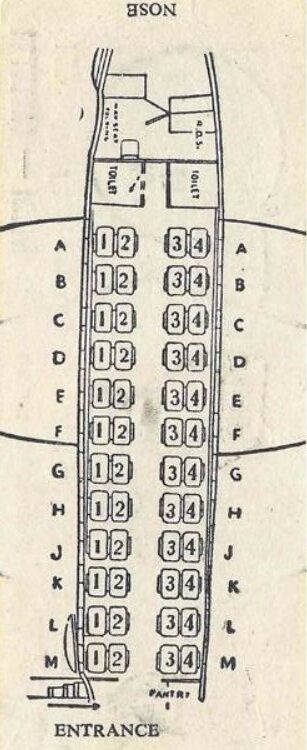

The earliest use of the alphanumeric method that I found was by KLM in 1950. The Lockheed Constellation plan that, ,as we saw earlier, in 1949 only showed numbers now has rows identified from A to M (row J omitted) with the seats across numbered 1 to 4.

The alphanumeric method was used by other airlines in the same decade as well, including BOAC, Indian Airlines, and Qantas. In most cases, the letters started at the front, but in at least one case (the Qantas Lockheed Electra II) it went from rear to front. The lettering followed the common alphabet (ABC) and, with 19 rows being the maximum of the period, reached the S in BOAC’s Britannia high-density layout. The numbering in all cases started on the left with 1, reaching 4, 5 or 6 on the right. I assume that BOAC’s Comet 4 (which started jet air transport in the Western world on October 4, 1958) had the same numbering method, but could not find evidence. Neither could I find anything about the 1952 Comet 1 cabin layout. I would very much appreciate hearing from readers if they have a numbered seat plan for the Comet 1.

Indian Airlines’ reverse sides of boarding cards for the Vickers Viscount 700 series show its characteristic forward opening, circular doors. The undated image on the left shows 44 seats and likely dates to 1957, the year it entered service. The one on the right is from a later date and has 48 seats.

Numeric-alpha

The earliest application I found of the numeric-alpha method was by United Airlines on their Boeing 377. This airplane type entered service in January 1950. This may well be the year United introduced this numbering system. A decade later it would become the world standard, but would they have realized that in 1950?

I found the seating diagram as it appeared on a period ticket envelope.

Other early users of the numeric-alpha method were TWA (now standing for Trans World Airways) in 1954 on their Lockheed Constellations, Eastern Airlines, also on the Constellation, and, quite surprisingly, the Soviet Union airline, Aeroflot.

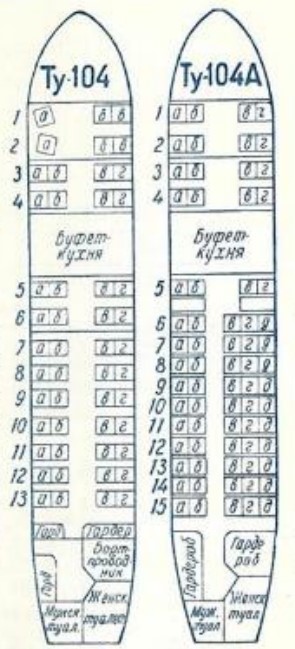

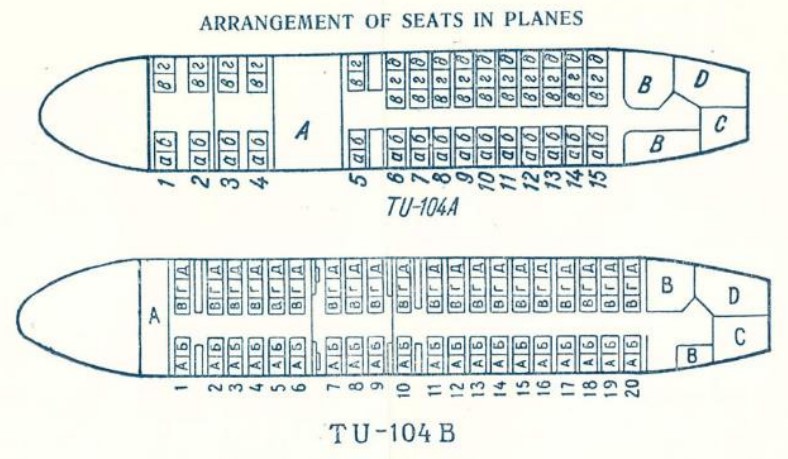

In 1956 Aeroflot introduced jet service and adopted the numeric-alpha way of seat numbering. The alpha element was in the Cyrillic script (aбв). I reproduce, from their winter 1957/58 timetable, the layouts of the Tupolev 104 (50 seats) and the improved Tupolev 104A (70 seats).

The inferior -104 model was quickly taken out of service and replaced by a second upgrade, as reflected in the summer 1959 timetable which shows the new 100-seat Tupolev 104B next to the Tu-104A.

More numeric-alpha examples, as well as non-conforming seat designations in the second (and final) part.

Sources

For this part, I used a variety of sources, including

- • Timetables (timetableimages.com, Björn Larsson,for KLM Fokker F VII A and Aeroflot, twice);

- • Safety cards Iberia;

- • Aircraftinvestigation.com;

- • eBay.com;

- • Air France museum;

- • SFO museum;

- • Antillesairboats.com.

Fons Schaefers

f.schaefers@planet.nl

April 2023