HISTORY OF SAFETY CARDS, PART 6: Recent Trends (1990s – Current)

By Fons Schaefers

This part is the final chronological edition of the history of safety cards, which, as we will see below, is now a century old. The next and last part will examine in-depth the subjects shown on the cards. The previous part ended around 1990. This part gives an overview of how safety cards evolved since then. It reviews developments in their general appearance, layout, artwork, and the special cards that emerged.

General Appearance

Under general appearance, I sort such characteristics as size and weight, orientation, folds, and paper quality. I’ll start with the latter – paper quality. Until the 1960s, safety leaflets were part of a package of documents that included menus, stickers, maps, postcards, and advertisement brochures. They were collectively held in a folder, called a flight kit, which was handed out to passengers. The safety leaflets were made of thin paper. As they were not subject to repetitive consultation by many passengers, this worked well. But when they became more common, and even mandated (see Part 4), they were no longer issued in the folder but stowed in seatbacks for repeated consultation by multiple passengers. This exposed them to wear and tear, so they needed to be more sturdy. Initially, this was done by using heavier paper. Later, cards were wrapped in plastic to provide durability, but were more commonly laminated, and eventually, printed on synthetic paper.

Size and weight – there is no standard for the size of safety cards. Many different sizes are in use, as long as they fit the seatback pocket. One of the largest was those by Ethiopian Airlines, measuring 22.5 cm by 33 cm (8.9 by 13 inches). Air France probably tops the smallest cards, at only 10 cm by 21 cm (4 by 8.3 inches). To ensure they do not disappear in the large seat pocket, Air France specifies a separate holder on seatbacks that uniquely fits their card.

Consistent with size and choice of material, the weight of cards varies. Most weigh between 20 to 40 grams (0.71 to 1.41 ounces), with outliers as light as 5 grams (0.18 ounces) as is the case with Aerogaviota’s An-26) or as heavy as 88 grams (3.1 ounces) with the Qantas 747-400.

Orientation – as none of the cards are square, they have a long side and a short side. This presents a choice between displaying the contents ‘portrait’ or ‘landscape’. The former is by far the most popular; few airlines use a landscape orientation. In some cases, a combination is used, with the front being portrait and the back (or the inside in the case of folded cards), landscape.

Folds – the multi-fold leaflets of the 1960s were replaced by cards with a double or a single fold or, more frequently, no fold at all. Some airlines use a folding method resembling French doors. In the Western world, where one reads from left to right, the fold is on the left side. In countries that read from right to left, such as some Arabic countries and China, cards may be folded on the right.

Layout

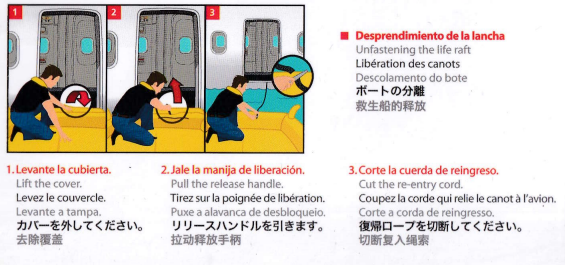

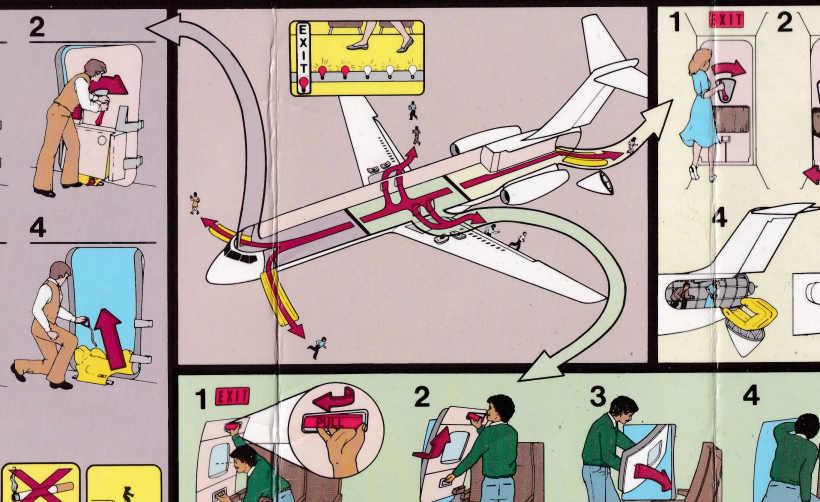

Layout is a generic term including the choice of text and illustrations, the type of illustrations (photographs, drawings, etc.), color, order of presentation, headings, use of space, etc. The trend of illustrations replacing text continued in the 1990s. All cards use illustrations, most with a minimum of text and some with text in support of illustrations.

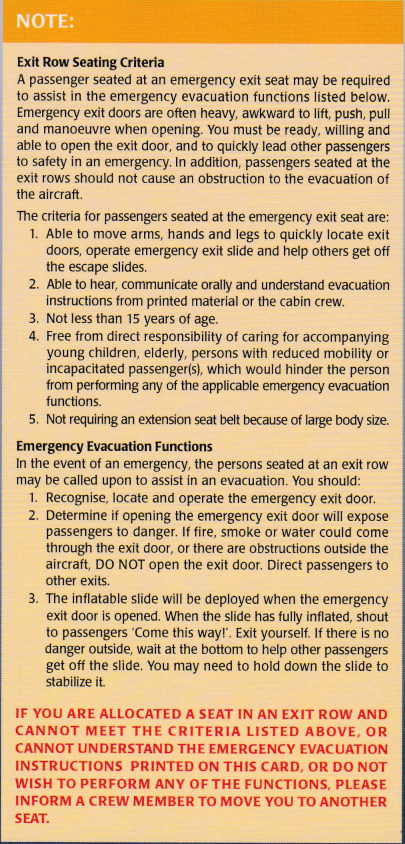

Text-only cards have disappeared. However, all U.S. airlines use a large amount of text to explain who may sit next to overwing exits. This is a direct result of a regulation that was introduced in 1990. Although many believe this regulation was aimed at instructing passengers how to open these self-help exits, its origin was different. That was a federal law that prohibited discrimination in air transportation based on handicap. There was an exception, though, and that was safety. The FAA defined the agility criteria exit row occupants must have to open the exit.

The airlines copy-pasted these written criteria on their safety cards. Some other countries adopted this practice and now such criteria are found on cards from Singapore Airlines, Brazilian, and Chinese airlines. Few of these airlines realize that the rule was aimed at hatches that come loose and are difficult to handle rather than easy-to-operate, powered doors such as on the A380. The text “awkward to lift, push, pull and manoeuvre,” used by Singapore Airlines, does not apply to such doors.

The use of photographs, which was quite popular in the 1970s through 1990s, particularly with U.S. airlines, has subsided. Among the last airlines to use them were American Airlines and China Eastern, but they also stopped using them. Cards using only black and white illustrations were still in limited use in the 1990s but have since disappeared. Color is the norm for the illustrations, with the card’s background normally white. In some cases, colors are used to link exit operation instructions to the exit locations on the airplane diagram.

The front page carries the name of the airline (or other organization, as the case may be), typically at the top, together with a description of the purpose of the card (safety information/for your safety/safety card/passenger briefing card/safety on board/safety instructions/important passenger safety information, etc).

Some airlines do not print their name. This challenges the collector to look for clues to identify the airline. This may be a code (e.g. ATL for Air Atlanta) or even a language script. Normally, the front page has safety information, but in a few cases, it is decorative only, such as by Canadian North, which uses photographs reflecting the Canadian North.

The most common form of illustrations are still drawings made by graphical designers. A new trend is computer-generated animations. An example of a computer baby is on the Xiamen 737-700 card.

Artwork

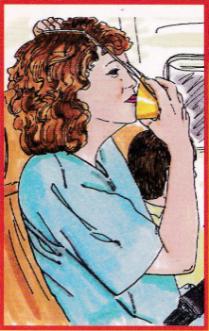

Artwork is about the style of the illustrations. One would think that the number of ways to show how to open a door or grab an oxygen mask is limited, but a study of safety cards proves the opposite. Each graphic artist has his or her way of rendering reality. This allows the collector to gather a nice collection of styles and fashions.

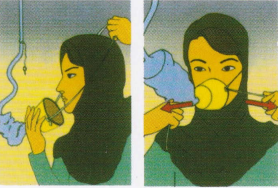

The most distinctive feature is how they portray humans. Overall, there is a slight preference for females over males. This may have to do with the dominant gender of cabin crew. The majority of persons being portrayed are white. While this makes sense for the Western world, even airlines in many other countries follow this, notably in Africa. Conversely, Japanese, Indian, and Iranian airlines are among the airlines representing local ethnicities and dress habits. In the U.S. and the UK, there is a tendency to portray persons of color. Most artists use photographs to make their drawings. As a result, some draw well-recognizable humans. The “Southwest woman” might be familiar to those who know her.

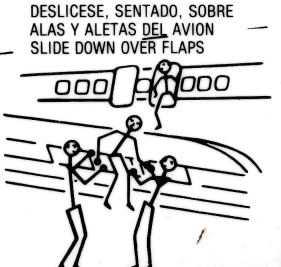

Other airlines apply more generic humans or even what some call “humanoids,” figures resembling humans. In the early 1990s British Aerospace sketched humans in black with a perfect ball as head. EasyJet copied this style 35 years later. Some airlines have managed to reduce humans to just a few lines.

Other artwork expressions consist of grouping the drawings over the cards. Most use a grid pattern which allows an orderly presentation of subjects. Air Baltic on its Avro RJ 70 card uniquely uses a different, relational ordering.

Artists also set their signature through the use of color. A nice example is the 2019 generation of Aer Lingus cards, designed by an Irish graphic designer.

Special cards

New Equipment

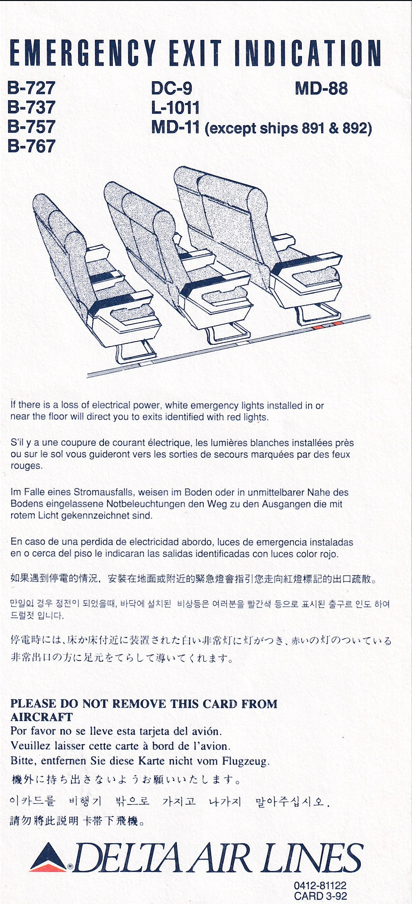

In the early 1960s airplanes were introduced with drop-out oxygen masks, and some airlines issued separate cards to explain these (see Part 3, TCA). Twenty years later, Delta printed a unique card to explain the floor lighting system, which they called “emergency exit indication.”

Categories of Operator

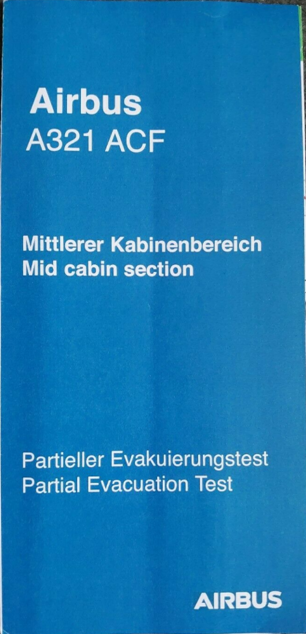

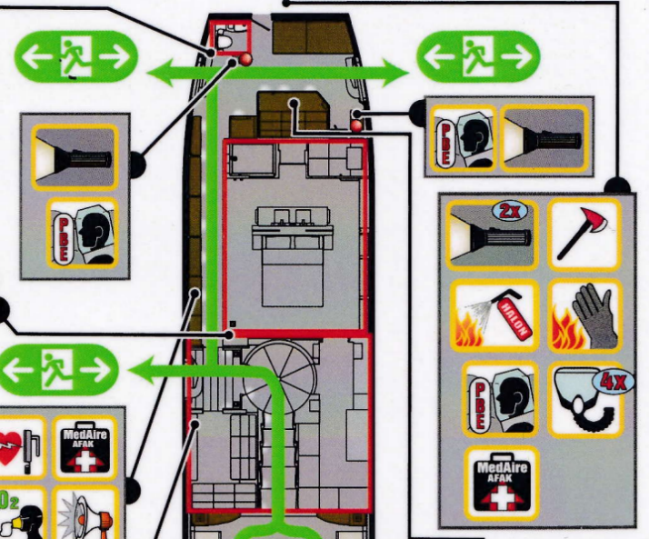

The use of safety cards is not restricted to regular airlines but extends to other cases where persons are transported by air. As with other collectibles with a vast range of samples, some collectors focus on subsets. This may be certain airplane types, operators from specific countries only, certain periods, or categories of operators. As to the latter, there are safety cards for government operators, business and VIP operators, military transport operators, and nostalgic operators, flying such classic airplanes as the Constellation, Catalina, or even a converted B-25 bomber. Additionally, there are cards for special operations such as zero gravity flights, research flights (e.g. the SOFIA 747SP), and the flying hospital (Orbis DC-10). Airplane manufacturers make safety cards for use during demonstration flights or as an example for their clients. They even make dedicated cards for evacuation certification tests, which are a one-off.

Often, non-airline cards display unique cabin elements. The VIP airplanes display luxury

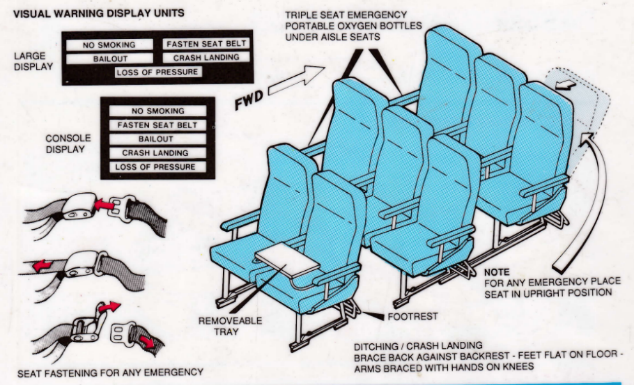

arrangements, including bedrooms with showers. One military card mentions bailout instructions.

User Group

Initially, airlines only used one card per airplane type which was good for all passengers.

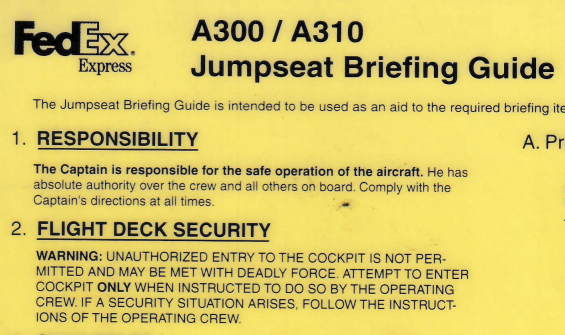

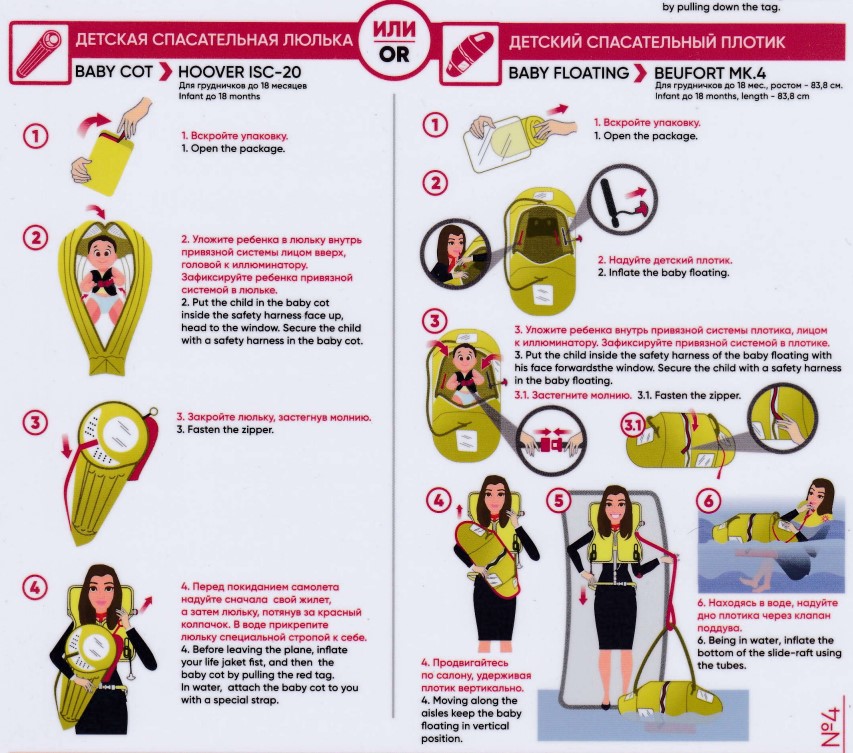

Gradually, cards came about aimed at specific passenger groups. These groups include cockpit

riders, non-cockpit jumpseat riders (with a warning that unauthorized access to the cockpit may be

met with deadly force!), passengers in exit rows, 747 upper deck passengers, passengers in seats

with seat belt mounted airbags, the sight impaired (with the card, or a book, in braille), physically handicapped, and children and infants. In the latter case, the cards are specific to life vests and handed out to the accompanying adult.

Kind of Operation

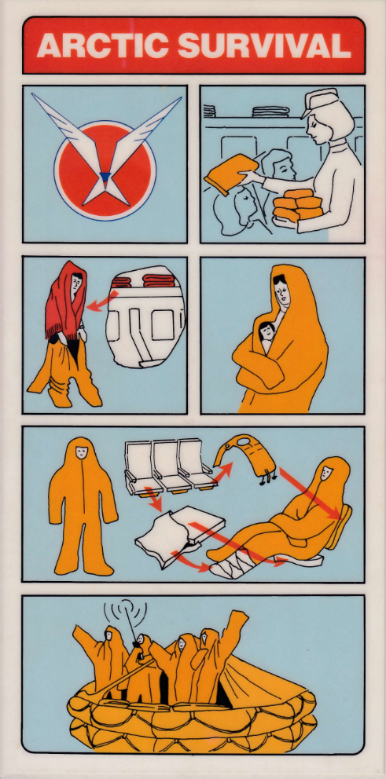

Few cards are specific to the kind of operation. In the 1950s there were leaflets specific for overwater operations explaining the ditching and life rafts. In the early 1960s extra cards appeared to explain the new oxygen drop-out systems were needed for high altitude operations. These are no longer in use. A more recent area of operation-related example is the Arctic survival card as used by Greenlandair.

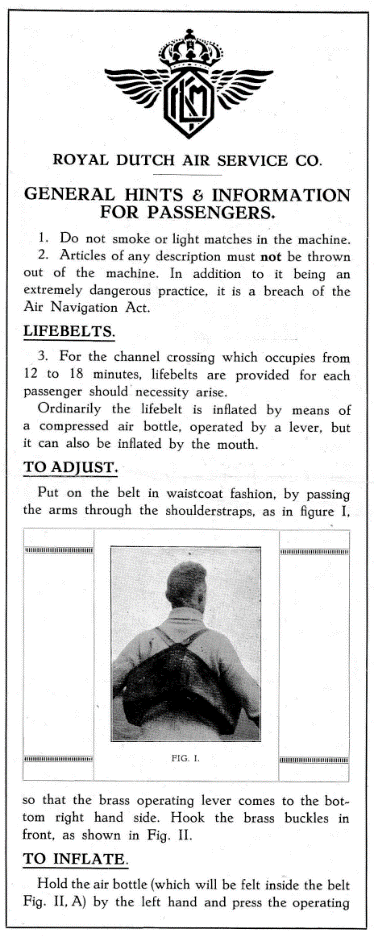

First safety leaflet?

Finally, I recently obtained a safety leaflet I believe is among the oldest ever. It was made in 1924 by KLM Royal Dutch Airlines, but it does not say so explicitly. How do I know it was from that year? The leaflet gives several clues. It describes a method of communication using ground signals that pre-dated the use of onboard radios, which KLM introduced later that year. The leaflet, which is in English, is a literal translation of an earlier Dutch version which claims KLM never had a fatal accident. But by the time it had been translated into English, this was no longer true and thus now omitted. The first KLM fatal accident was in April 1924. This confirms the first safety card was issued a century ago.

Fons Schaefers / November 2024

e-mail: f.schaefers@planet.nl

Tags: airlines, Safety cards

Trackback from your site.