HISTORY OF SAFETY CARDS, Part 4: 1960s – Mandated!

By Fons Schaefers

Pioneers

Until the early 1960s survivability of transport aircraft accidents was not an issue. The attitude towards accidents was that they were a fact of life. All funds for safety should be allotted to learning from them so as to prevent future accidents. Investigations focused on the causes of accidents, not on their consequences in terms of survivability. It took two pioneers a decade or more to teach the aviation world it was worthwhile to expand the focus to survival factors, also known as “passive safety.” They proved that many improvements could be made in making aircraft more crash-worthy.

Those pioneers were Hugh DeHaven (1895-1980) and Howard Hasbrook (1913-2000). In 1942, DeHaven started the crash injury project at Cornell University (New York). In 1953, this was split into an automobile section, which he further developed (and which inspired car safety belts and Ralph Nader’s “unsafe at any speed”), and an aviation section. The latter was run by Hasbrook, who in the 1950s and early 1960s did pioneering work in investigating survival factors of major aircraft accidents. One of his earliest investigations was that of the National Airlines DC-6 crash near Newark in February 1952. He was the first to make sketches of the crash kinematics illustrating how and why aircraft broke up. Curious? Then go to https://archive.org/details/dtic_AD0030398/mode/2up

Not only were his methods innovative and his findings unprecedented but he also spent much time and effort in advocating them to airframe manufacturers, airlines, and aviation authorities, not only in the US but also abroad. His recommendations were well ahead of their time. Already in 1952, he suggested passenger seats be tested dynamically. It would take more than four decades before this became mandatory, first in the USA and later worldwide.

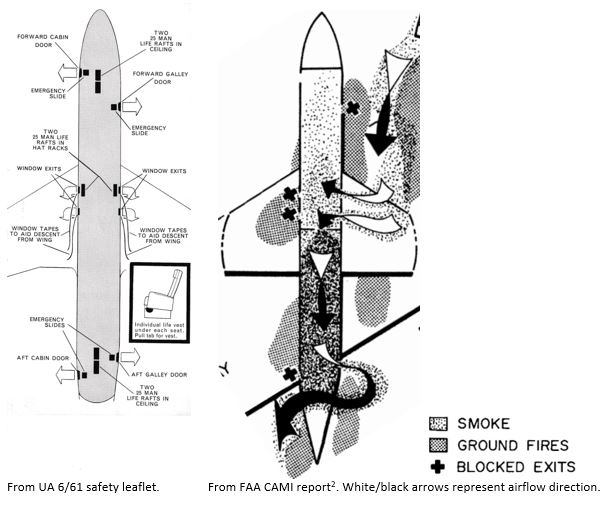

His safety campaign was successful. In 1963, the FAA proposed rulemaking for a host of cabin safety measures, ranging from improved exit signs and markings to mandatory evacuation demonstrations by airlines, and passenger briefings. Of course, it was not only Hasbrook who triggered the FAA to come into action. Less than three years after the first jets entered service in the US, the first crash of a jet with survivability issues happened: a United Airlines DC-8 at Stapleton Airport in Denver, CO, on July 11, 1961. Hasbrook investigated the circumstances in the cabin, which were painfully shocking [1]. To understand what follows, I reproduce the exit plan of United’s safety leaflet next to a sketch of the accident’s wind-steered smoke and fire pattern. The safety leaflet is dated 6/61, so released just weeks before the crash.

[1] FAA CAMI AM 62-9, Evacuation pattern analysis of a survivable commercial aircraft crash

The crash itself was mild, but a fuel fire erupted, gradually entering the cabin. All passengers in the first class section, which was large and extended from the front back to the wing and included all four overwing exits, survived. In the tourist class section, however, 16 passengers died of smoke inhalation. In that section, there were only two exits, only one that could be opened. The aisle was narrow and the divider between the two classes reached from floor to ceiling, obscuring the view forward. There was no indication, such as a sign, that there were exits beyond it. No passenger briefing had been given, even not after it had become clear that the landing would not be normal.

Whether the tourist passengers had boarded aft and were thus unaware of the forward section and the exits there, is not reported but it would not surprise me.

This accident was the first of a jet that should have been survivable to all occupants. It provoked a lot of attention. Four months later, a survivable, yet fatal accident occurred with a Lockheed Constellation on a military charter with young army recruits, many of whom died. That accident got much less attention for reasons unknown. In any case, the time was ripe for improved cabin safety measures. Something had to be done to increase the chances of passengers who survive the impact to escape from an aircraft before a fire overtakes them. The Federal Aviation Agency (FAA) came into action and, as said, in 1963 proposed a plethora of new cabin safety regulations. [3]

[2] FAA CAMI AM 70-16, Survival in emergency escape from passenger aircraft

[3]NPRM 63-42, Federal Register October 29, 1963

1965 – First Safety Card Rule

Although in 1962 Hasbrook recommended passengers be instructed in evacuation procedures prior to “any anticipated, unusual landing situation,” he did not go as far as asking for safety cards. Neither, in 1963, did the FAA. But, at a hearing in June 1964 on the proposed regulations, somebody suggested safety cards as an additional measure. By whom, I could not find, but I would not be surprised if it was one of those operators already voluntarily using them. United Airlines, perhaps?

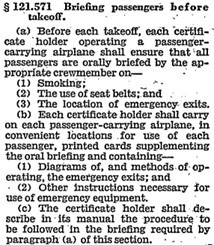

When the final rule was issued in March 1965, the FAA mandated printed safety cards for all US airlines per June 7, 1965. Here is the text of the regulation – focus on section (b):

As you can see, the requirements for the card were simple. They must show:

- diagrams of the emergency exits;

- methods of opening emergency exits;

- other instructions necessary for use of emergency equipment.

These requirements were broadly worded. The first was generally interpreted as showing the location of the exits on an airplane plan. The second was met by illustrating how to open the exit. The third one was quite vague – does this include emergency equipment like fire extinguishers or first-aid kits? Not so if we look at the safety cards of the time. They showed oxygen masks, escape slides and for overwater operations, life vests and, occasionally, life rafts, but nothing more.

1965 Safety Cards

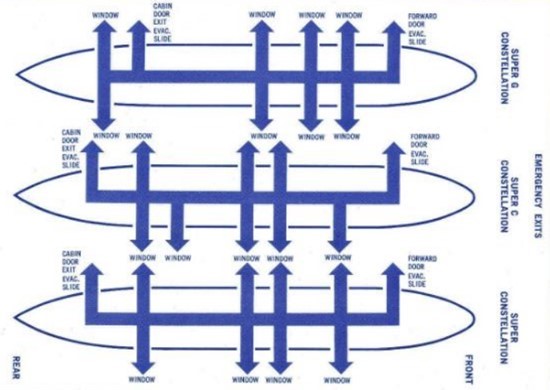

The new rule must have triggered several US airlines to issue a new range of safety cards. I will discuss some that directly resulted from it and some that were simply continuations of what was already there. Eastern Airlines issued new cards immediately, in June 1965. Eastern was one of the airlines that had separate cards for each aircraft type, as opposed to fleet cards. For an example see the DC-7 card in Lester Andersons’s July 2020 contribution below. Eastern’s Constellation card was a bit hybrid, as it showed three variants, each having a different exit layout. I reproduce the trio here, rotated 90 degrees to allow easier reading of the exit captions.

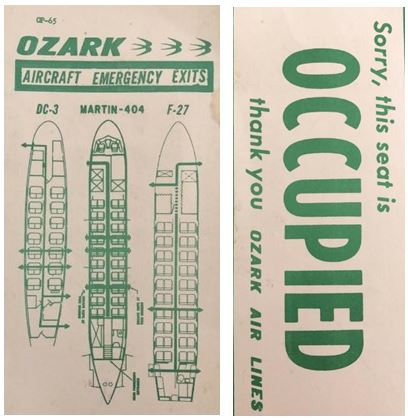

Ozark Air Lines had a fleet card labeled “OP-65,” which may have been in response to the new rule. It showed exit locations for three aircraft types: DC-3, Martin 404, and Fairchild F-27. This mix indeed uniquely reflects their 1965 fleet composition so it was likely released that year. But other than exit locations, nothing else was shown so it did not fully meet the new rule. On the reverse side, it said “occupied” in large letters, for passengers to reserve their seats during transit stops.

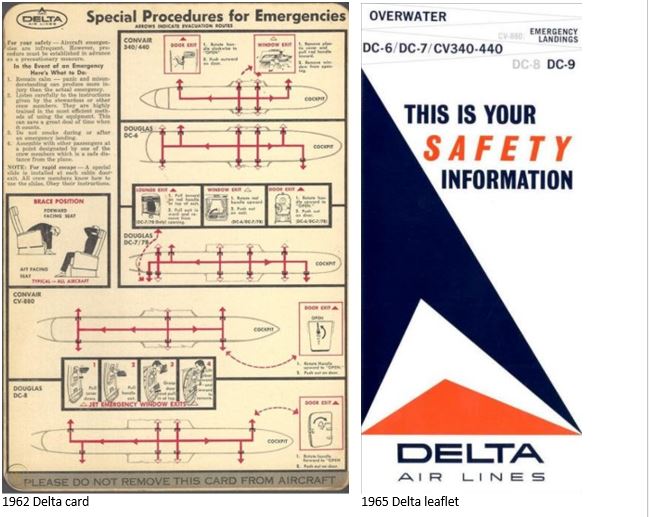

Delta Air Lines used fleet cards before the cabin safety card rule came into effect. I present the card used in the period 1962-1965, copied from the internet. It was called “Special Procedures for Emergencies.” This shows aircraft plans for the Convair 340/440, Douglas DC-6, DC-7/7B, DC-8, and Convair 880. Note the cockpit is on the right. The emergency exits consisted of either doors or window exits and were well indicated, with the means of opening explained in small panels.

This card survived the June 1965 regulatory change, as it already met it.

The single card was replaced about six months later by a leaflet with four vertical folds, like an accordion. It was issued in conjunction with the introduction of the new DC-9. In appearance, it was a complete makeover. The rather technical presentation was gone and replaced by a more attractive and modern look, making optimum use of the Delta logo. Other than that, it featured the same types as the previous card. I reproduce the front, but see also Brian Barron’s July 2017 entry.

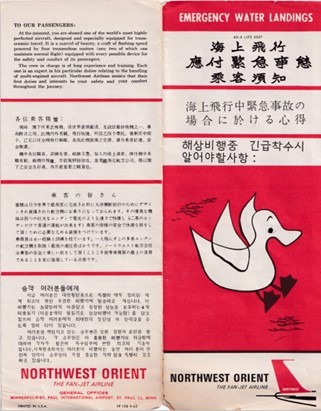

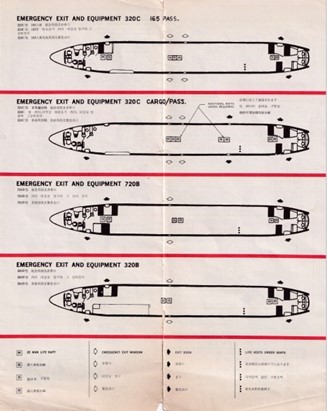

Northwest Orient Airlines renewed its leaflets in September 1965. Northwest re-issued the “emergency water landings” leaflet in use since the early 1950s. While it indeed included diagrams of four different types showing exit locations, it lacked the method of opening them. This would rate it as not meeting the new rule. However, Northwest, while continuing this line of overwater leaflets, augmented them with a separate leaflet explaining the automatic oxygen system, exit locations, and opening method. Thus they met the new rule. On that leaflet, the Boeing 727 was added to the overwater types, but not the Lockheed Electra and DC-7C. Apparently, separate cards were made for those, non-automatic oxygen-equipped types (see Lester Anderson, July 2020).

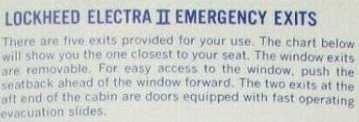

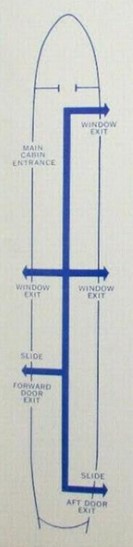

Western Airlines changed its cards in December 1965. They were fleet cards, showing three types on one leaflet: Boeing 720B, Lockheed Electra II, and Douglas DC-6B. It had airplane plans, exit operation method panels, and more. I reproduce the plan for the Electra as that has some interesting features, which could easily have led to passenger confusion:

- the main cabin entrance door, forward left, was not shown as an emergency exit. This was allowed under the period regulations;

- the door on the left aft side is marked as “forward door exit,” even though it was well aft, being situated behind the wings.

1967 – First Amendment to the Safety Card Rule

I could not find any cards dated 1966. That year however stands out as it saw a proposal by the FAA for already modifying the new briefing card rule. Two new requirements were presented for public consultation, which the FAA believed would improve passenger knowledge and avoid confusion:

- each passenger over 12 years of age must be given one copy of the printed briefing card upon entering the airplane;

- the cards must be pertinent to the type and model of airplane being used on the flight.

The first proposal met with resistance from the airlines and was not adopted. The second, however, was well received and took effect on October 24, 1967:

This meant the end of fleet cards, at least in the USA.

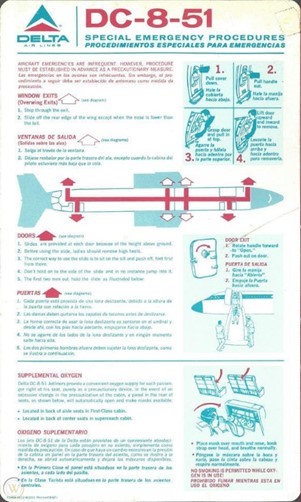

Delta responded quickly and first issued type-specific cards in September 1967, one month before the rule deadline. They diligently made separate cards for each type and model, as the new regulation stipulated: one each for the DC-9-14, DC-9-32, DC-8-33, DC-8-51 (shown), CV-880, etc.

Five years later (8/72), they joined the two short DC-8 models (DC-8-33 and DC-8-51) on one card, as the exit locations and method of operation were identical. Yet, on the cover, a different type appeared. Delta later corrected that.

1968 and 1969 Safety Cards

The revised regulation led to an abundance of cards. Like Delta, the major carriers, aware of the upcoming rule, had already started re-issuing their cards in 1967. Scroll below to the articles by Barron and Anderson in this Captain’s Log safety card section to see some examples.

The next two years saw many more airlines introducing or revising them. Let me reproduce a selection to illustrate the artwork and methods of presentation.

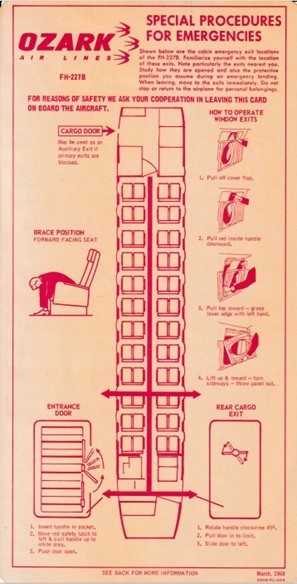

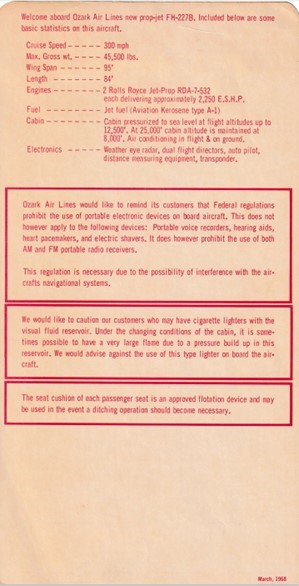

in March 1968, Ozark Air Lines issued this Fairchild FH-227B card. On one side it has some technical data, plus text cautions about electronic devices, lighters, and a notification about flotation cushions. On the reverse side, there is graphic safety information showing exit locations and their operation.

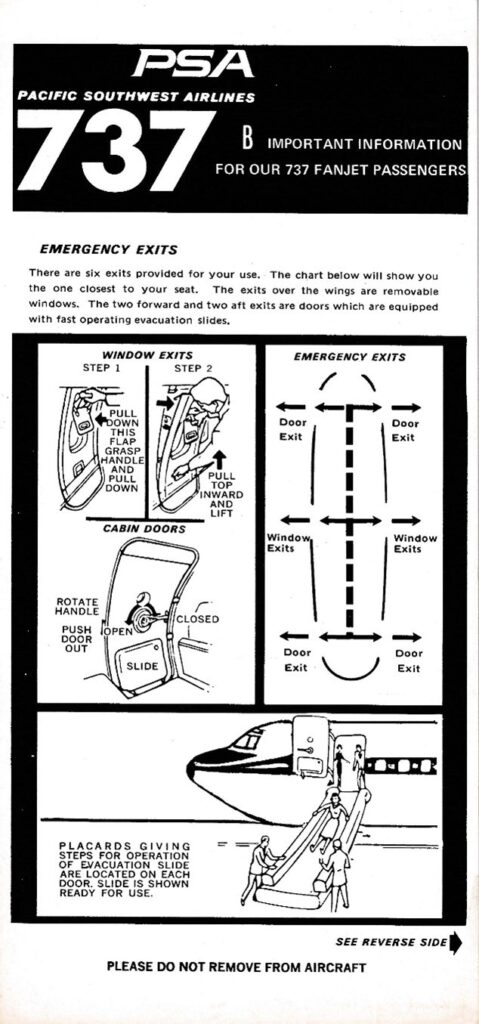

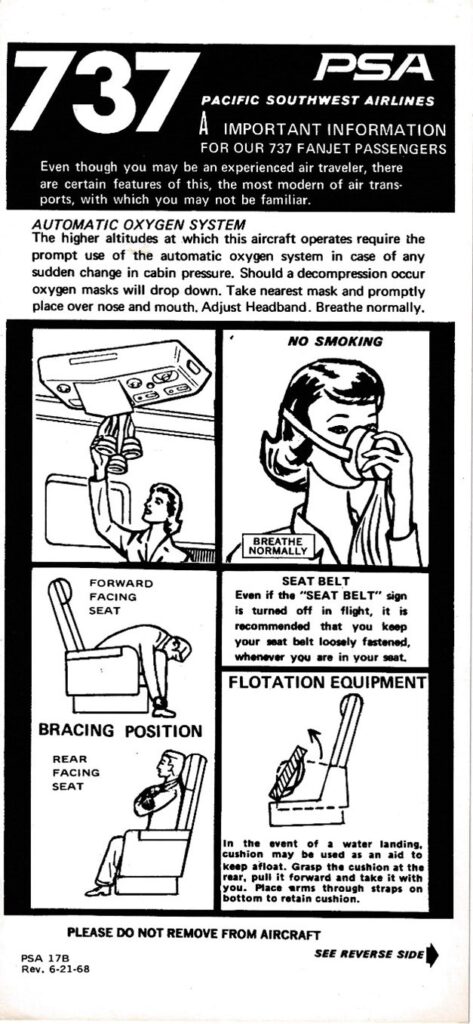

Pacific Southwest Airlines introduced the Boeing 737 in September 1968, a brand new aircraft type. They had the safety cards prepared well in advance, as evidenced by the issue date: June 21, 1968. Emergency exit location, operation, and the slide were shown on one side; oxygen, bracing position, and flotation equipment were on the other. Note the rather primitive way of portraying the cabin.

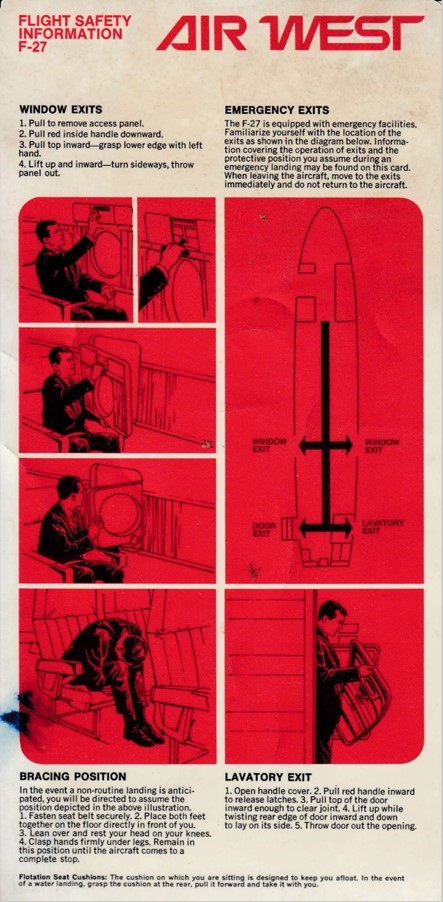

Air West was formed in April 1968 by a merger of Pacific Air Lines (which started in 1941 as Southwest Airways, not to be confused with the later Southwest Airlines), Bonanza Air Lines, and West Coast Airlines. They all operated the Fairchild F-27. Their operating area covered the eight westernmost United States, so the new name, Air West, was apt. Air West’s December 1968 card was identical on either side, but for the language: English on one side, Spanish on the other. Safety information was limited to bracing position, flotation seat cushions, exit locations, and operation of the window exits plus the exit in the lavatory. The F-27 (both as built by Fokker and Fairchild) was probably unique in that one exit could only be accessed via the lavatory! For that purpose, its door needed to be secured open during take-off and landing. How the oppositely located integral stair-equipped entrance door opened was not shown. The illustrations were black on red, which would not have helped in conditions of poor lighting. When former TWA-owner Howard Hughes bought Air West in 1970, it became Hughes Airwest. In 1980 it was bought by Republic Airlines, which itself was absorbed by Northwest Airlines in 1986, which, in turn, was acquired by Delta Air Lines in 2008.

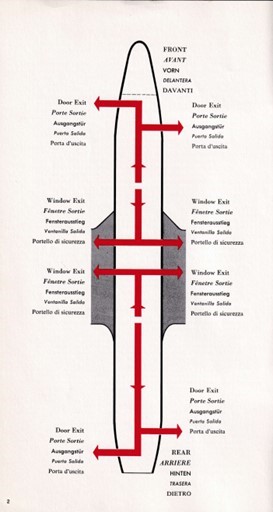

In February 1969, TWA issued an extensive 18-page booklet for their 707 “Starstream” in five European languages. Large in size and print, and well-illustrated, not only are exit locations and their operation explained as well as oxygen, life vests, and rafts, but also seat belts, smoking, and portable radios and TVs. It had separate pages for infant life vest use and even how rescue is organized. The exit plan shows internal escape routes which are confusing in the overwing exit area. The longitudinal arrow lines are not connected between the two pairs of overwing exits. Was there a barrier? No, actually, there were seats between these exits. Probably TWA wanted to stress the importance of the overwing exits for passengers seated in the center cabin and omitted this detail.

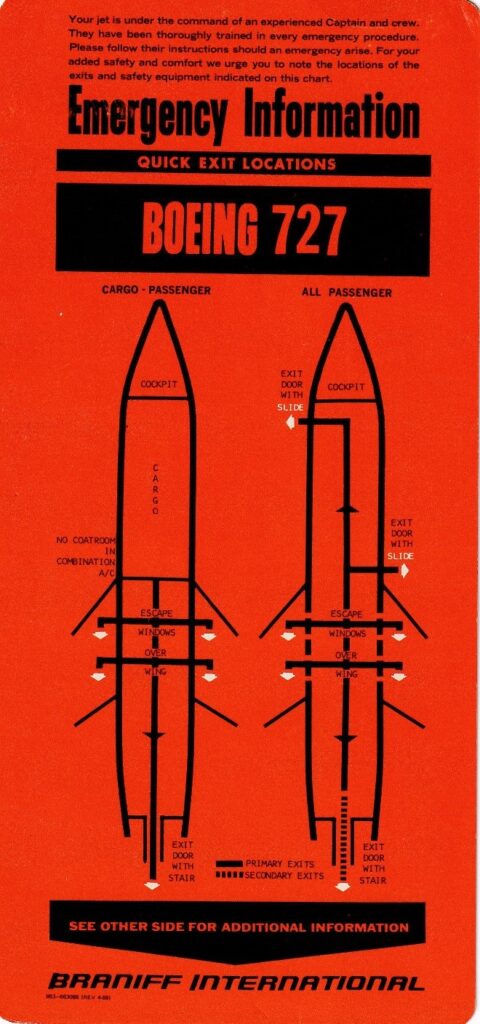

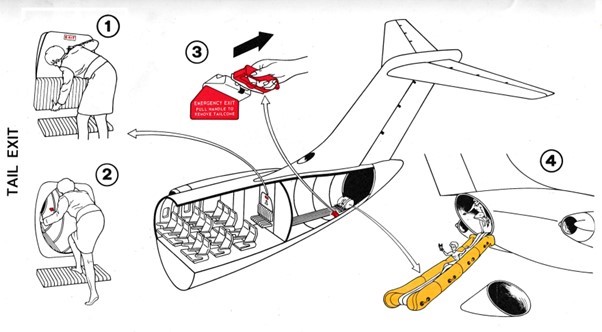

Braniff had much simpler cards, two sides only, with “quick exit locations” on one side and exit operation (plus smoking, seat belts, oxygen, and bracing opposition) on the other side. On the April 1969 card, two variants of the 727 are shown: “cargo-passenger” and “all passenger.” Would this meet the regulatory qualification for same type and model? The cargo-passenger version shows the cargo compartment forward of the wing. The only exits available for passengers are those over the wing plus the tail exit, which is ranked as a “primary exit.” For the all-passenger version, that exit is a “secondary exit.”

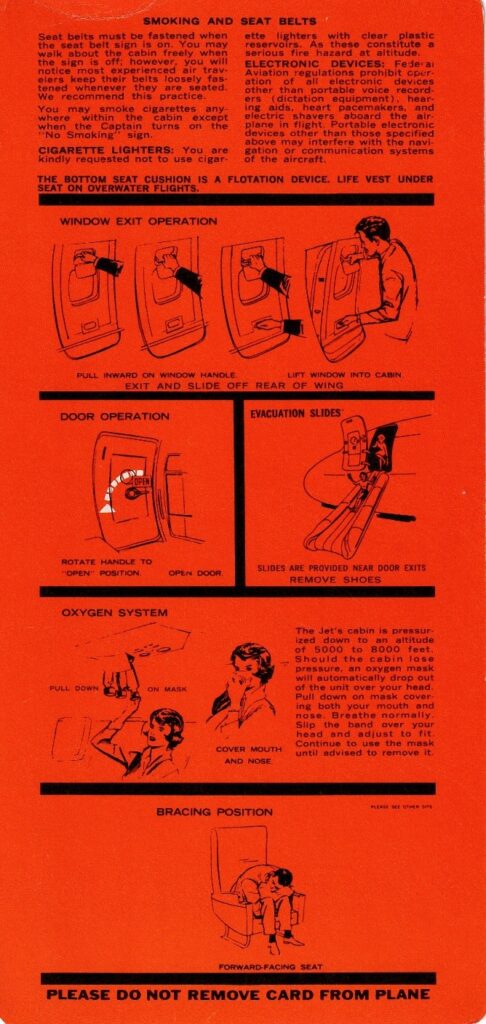

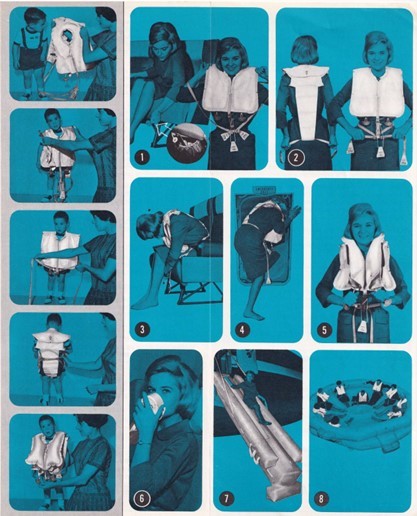

Like TWA, Pan American issued a booklet for their Boeing 707. It covered the same subjects as TWA did, but was smaller and in three more languages (Portuguese, Chinese, and Japanese). I reproduce from their July 1969 edition the front page and the illustration page. The latter folds out so it can be read along the subject page of the selection.

Outside the USA

The new rules directly affected US carriers. But they also inspired other countries to adopt the same, or similar regulations. I highlight three airlines from three European countries.

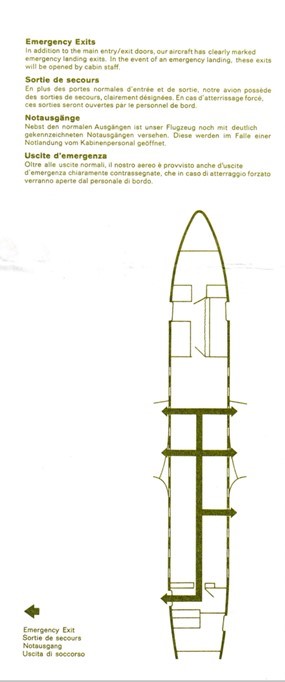

In Switzerland, Swissair replaced its fleet leaflets with type-specific leaflets around 1965, so actually before the US did. I show the type-specific leaflet for the Convair Metropolitan, the name that the Swiss used for the Convair 440. It is undated but I estimate it to be from around 1965.

Sometime in the 1950s, KLM of the Netherlands introduced a generic leaflet with emergency preparation instructions in six languages and included illustrated life vest instructions. Unfortunately, I do not have a copy to show. It was not a fleet card as it lacked type-specific information, like aircraft diagrams, but was likely used on all types. Exit information was limited to one line:

“The escape hatches are marked ‘Emergency exit’ and the method of opening them is clearly indicated.”

It must have been used well into the next decade. For the DC-8, DC-9 and “Super DC-8” (DC-8-63), introduced in 1960, 1966, and 1967 respectively, it was augmented with separate leaflets for oxygen use, in no fewer than 12 languages, reflecting KLM’s standing as a global airline serving passengers of many tongues. Here is a poor-quality internet reproduction of the top portion of the DC-9 oxygen card.

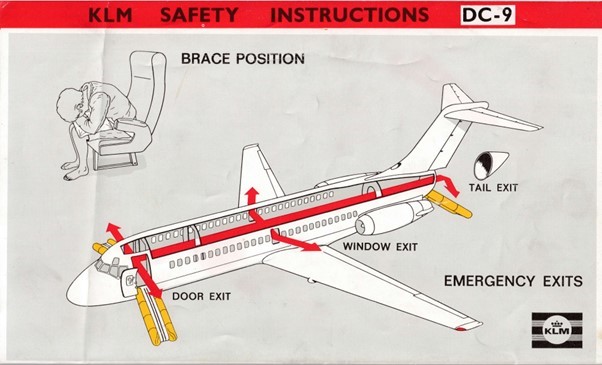

Later, and likely prompted by the developments in the USA, KLM replaced the generic leaflet and oxygen supplements by type-specific cards. That change was drastic. From nearly text-only, KLM went for a low-text, all-graphic presentation, quite possibly to avoid the burden of having to translate in so many different languages. The new cards showed exit locations and their operation plus the brace position, oxygen use, and life vests. None of the early cards had an issue date making it difficult to determine a year. My best guess is 1968. There were separate cards for two versions of the DC-8 as well as two versions of the DC-9, all uniquely coded. The DC-9 cards carried the striped KLM logo which lasted until 1972. The DC-8 cards did not have any logo, possibly because they regularly flew for partner airlines such as Garuda Indonesia and Viasa (Venezuela) and KLM wanted to avoid confusion on the part of the passengers. I reproduce two panels from the DC-9 series 10 card.

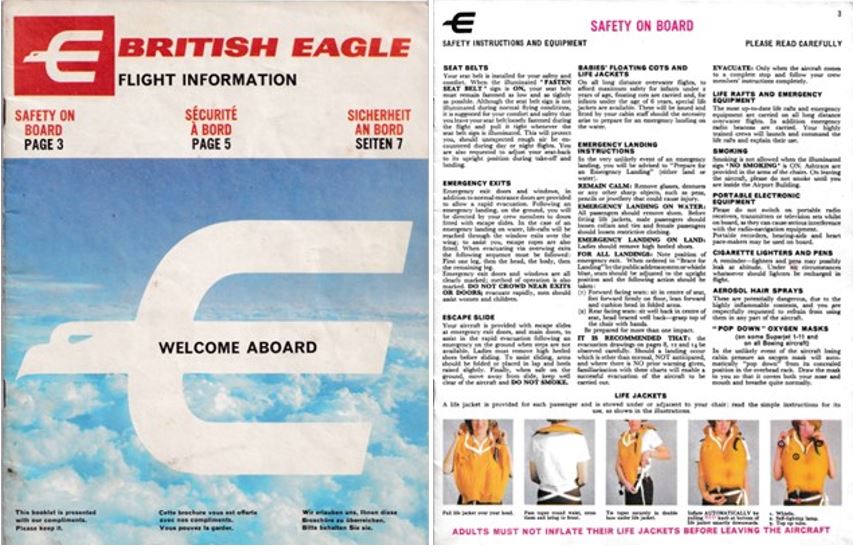

The UK was one of the few countries with a strong civil aviation industry and authority, which had its own agenda. It did not follow the US as closely as many other countries. Many of the cabin safety measures invented in the US took a long time before they landed in the UK. In Britain, the airlines presented passenger safety information in their traditional in-flight magazines until well into the 1970s without issuing separate cards. I show the 1968 example of British Eagle, one of the independent airlines of the time. On the front cover, there is a reference to the safety on board pages, in three languages. The instructions are extensive and clear, but in text only, except for pictures of life jacket use. Further down the magazine technical data appears for the airplane types, with exit diagrams. I reproduce those for the Britannia (top) and the abundantly-exited Viscount (bottom).

In the next part, I will review safety card developments in the 1970s and 1980s.

Fons Schaefers / January 2023

Email: f.schaefers@planet.nl

Tags: Safety cards

Trackback from your site.

Lester Anderson

| #

## Comment SPAM Protection: Shield Security marked this comment as “Pending Moderation”. Reason: Failed AntiBot Verification ##

Very interesting article. It was interesting to see variations on the cards of airlines I never had the opportunity to fly.

I ran across another challenge to airlines and flight crews–the differences in aircraft they purchase from other carriers. When TWA bought three 767-300’s (2 from Aer Lingus and 1 from Condor) different crew safety instructions and I assume safety cards were needed because the two Aer Lingus had only doors (three similar to other TWA doors and one that was always armed and used for emergency only) but no overwing exits, and the Condor had the typical two overwing exits. This comes from the 3/4/94 Flight Operations Training Bulletin.

And thank you for the reference to my prior postings of safety cards.

Reply