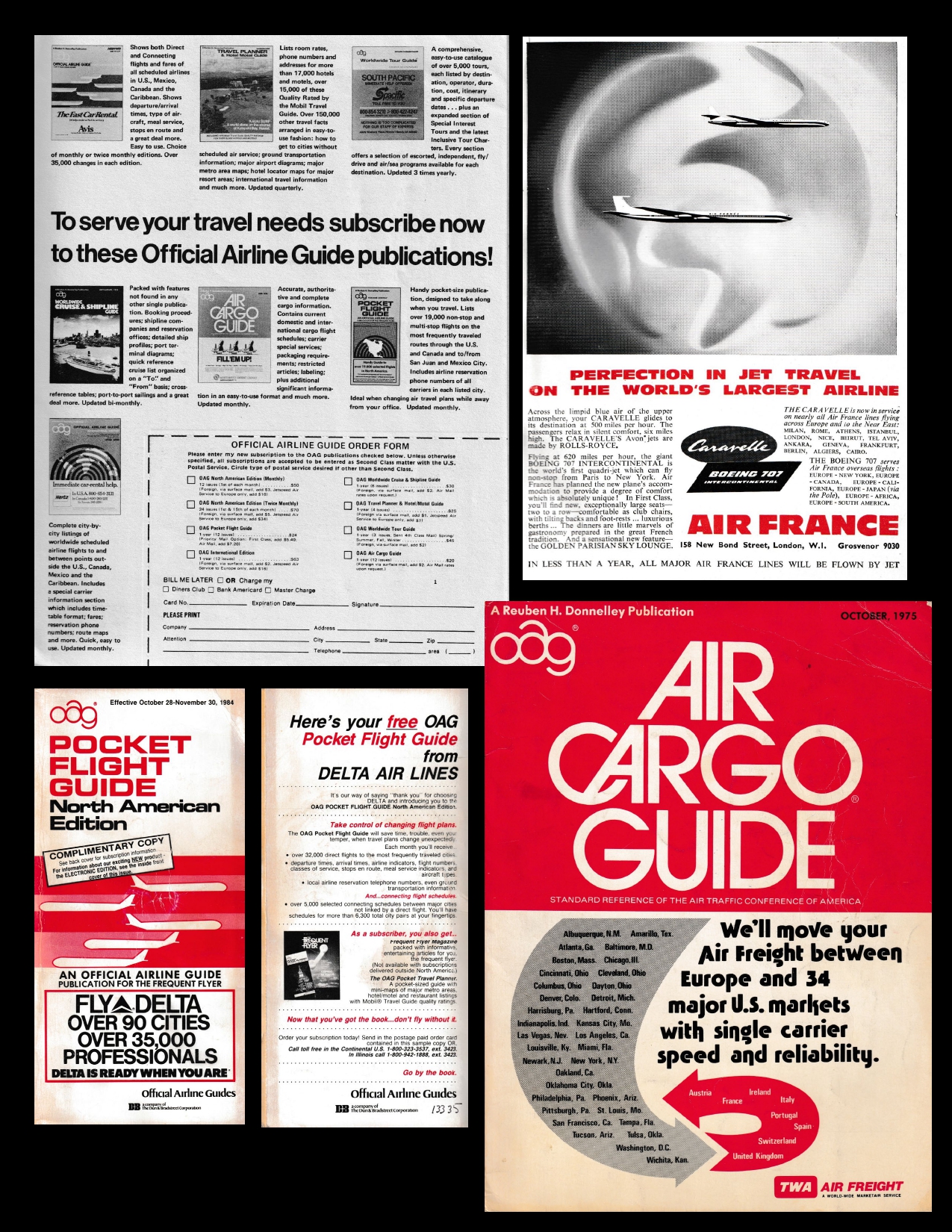

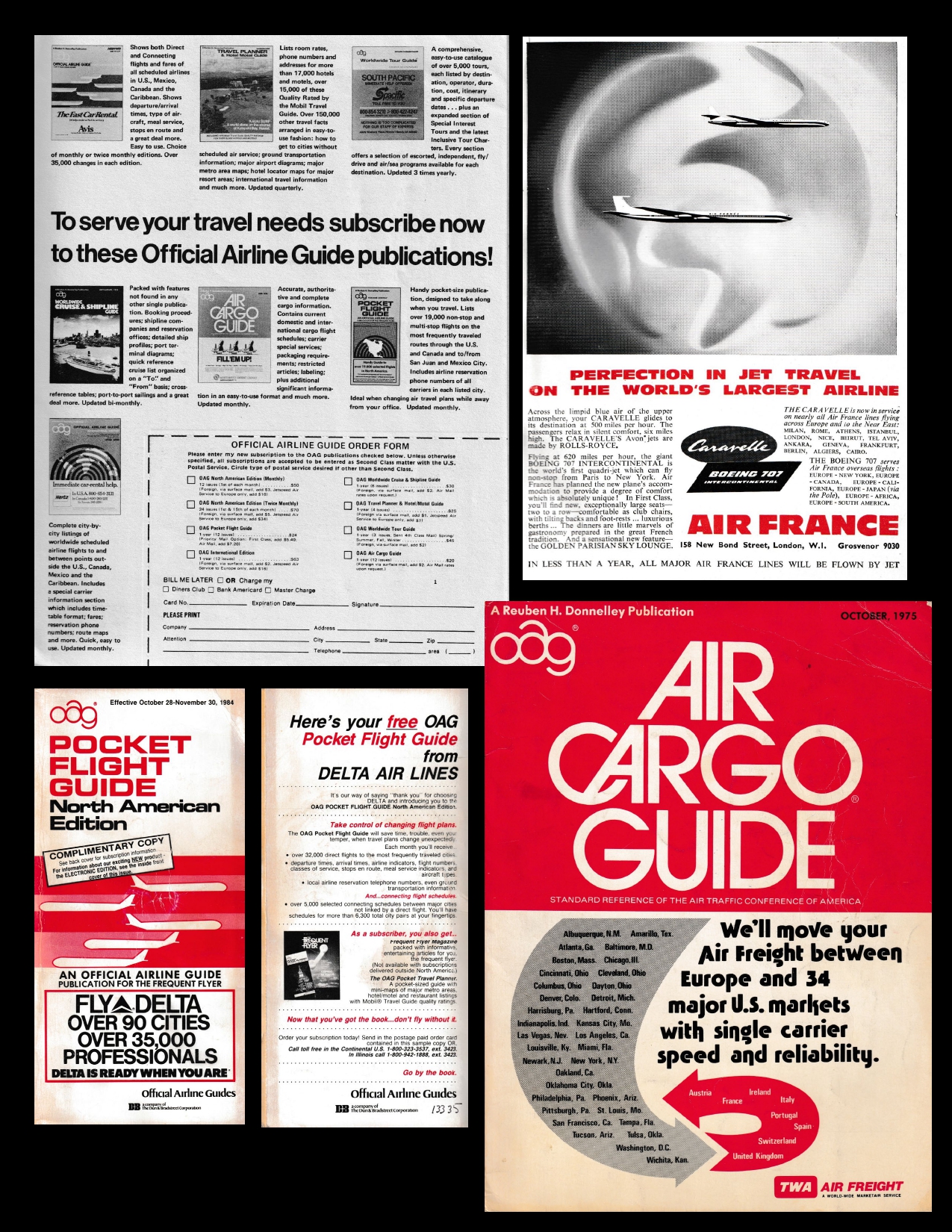

Airline Schedules,OAG,Official Airline Guide,timetables

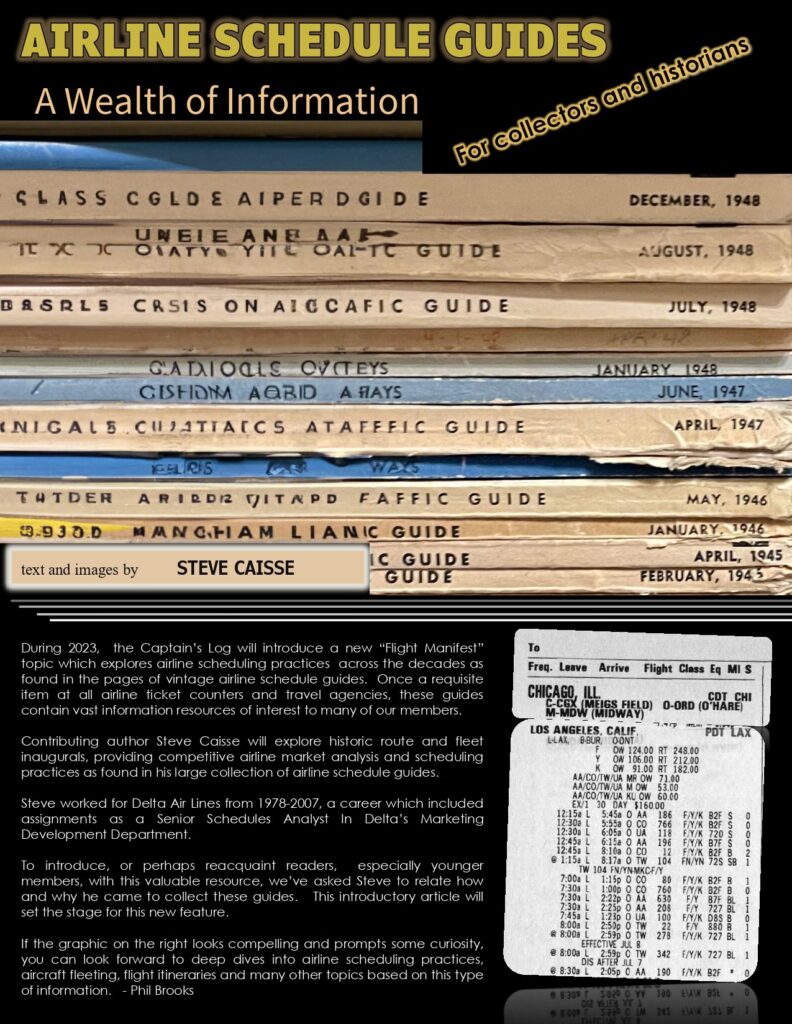

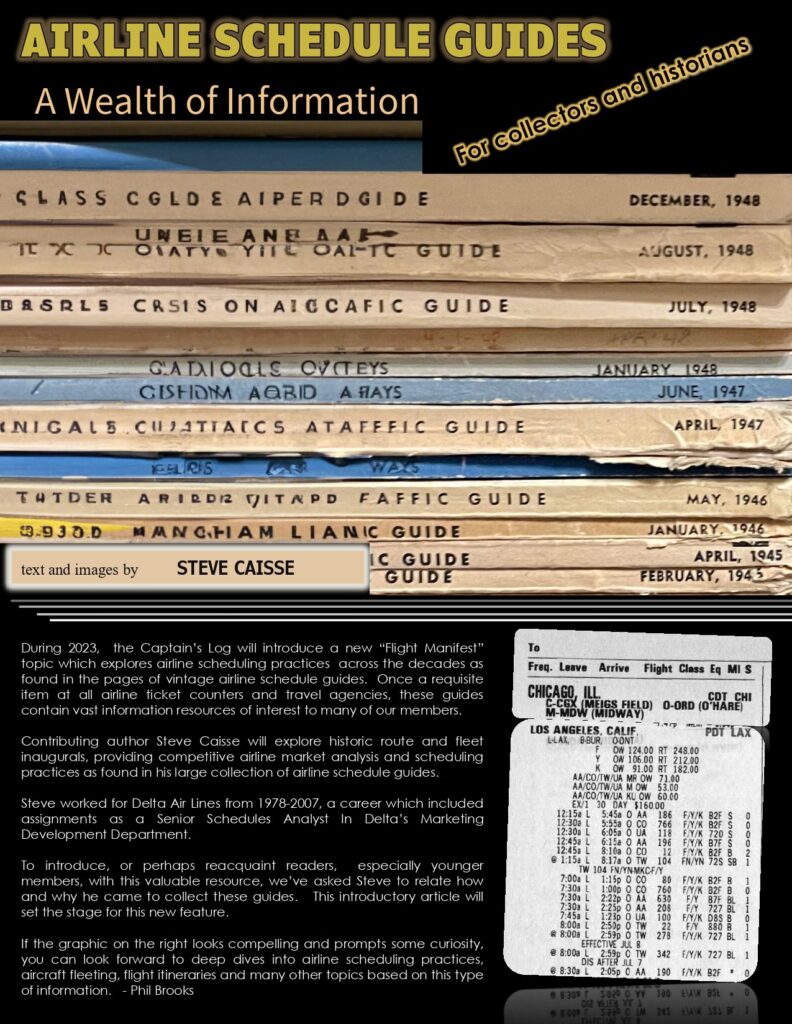

Airline Schedules: A Wealth of Information

By Steve Caisse

Follow this link to view this article as a pdf.

Follow this link if you’d prefer to download this article as a .pdf.

Airline Schedules,OAG,Official Airline Guide,timetables

By Steve Caisse

Follow this link to view this article as a pdf.

Follow this link if you’d prefer to download this article as a .pdf.

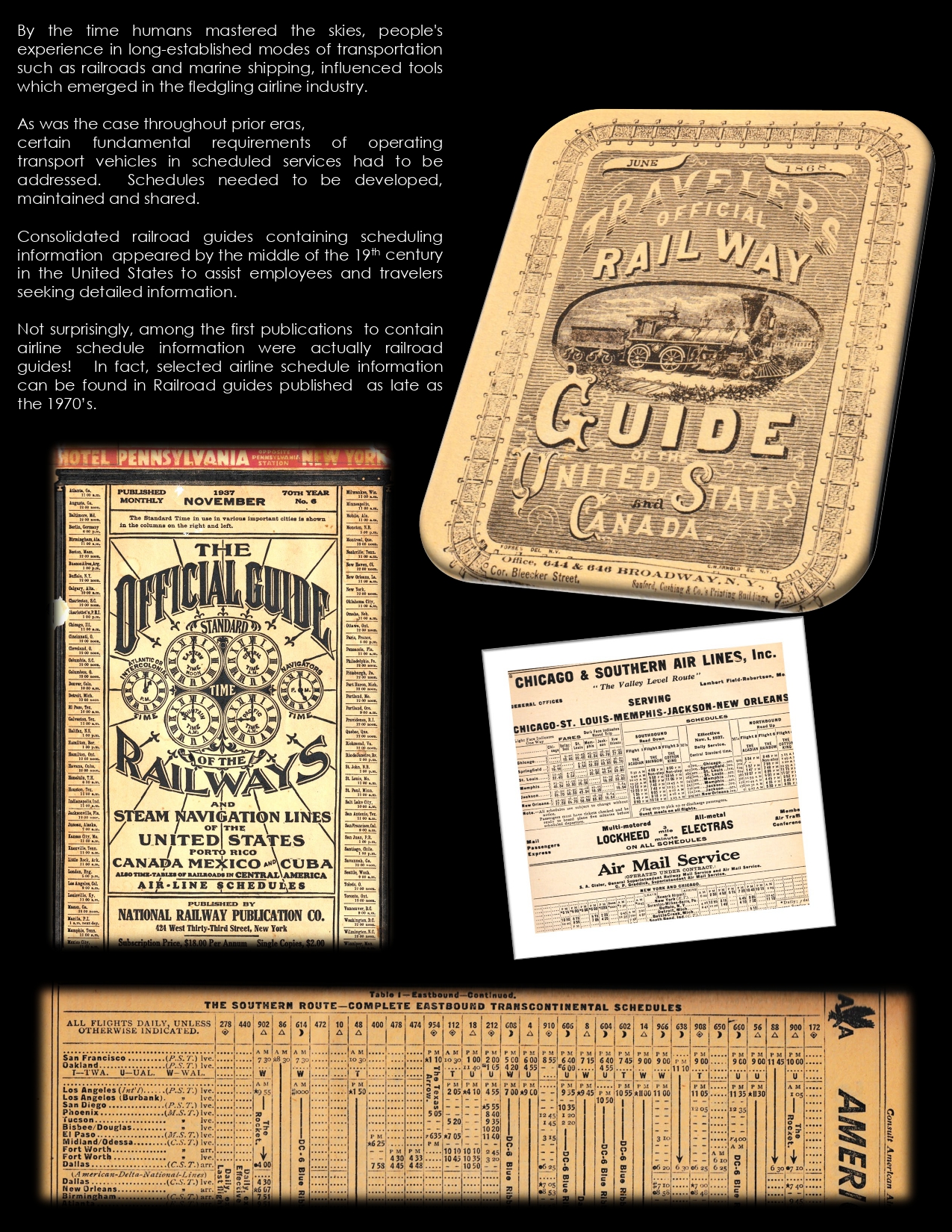

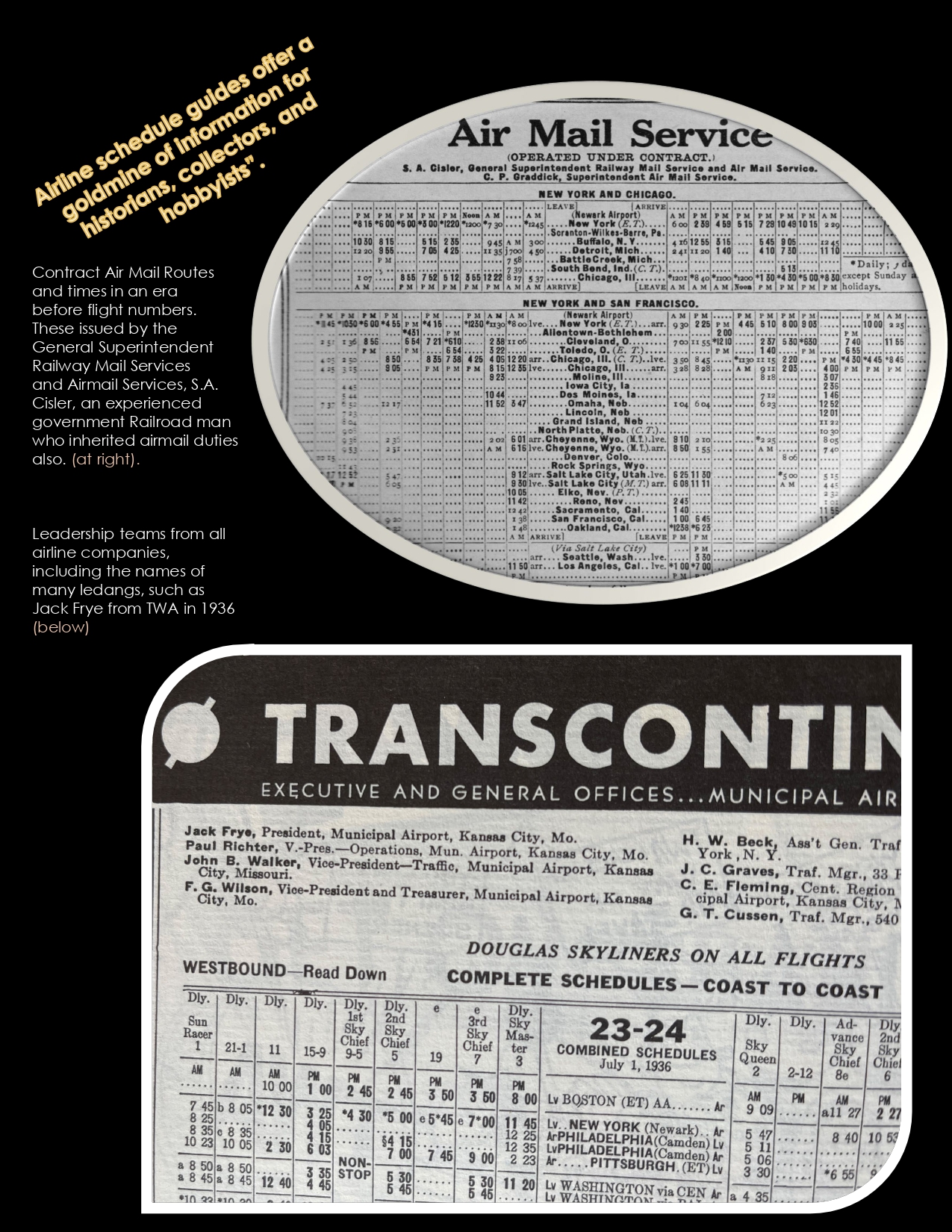

Written by David Keller

The Airline Deregulation Act was signed into law by President Jimmy Carter on October 24, 1978. This piece of legislation had a wide-ranging impact, and the airline industry in the US would never be the same.

Some of the major changes were:

The most immediate impact of the legislation was that the established airlines were able to take advantage of their new freedom to add routes, largely by applying for “dormant” routes, as well as one other route they could add each year without needing to receive CAB approval. Since these companies had fleets, employees and the required certifications, they would be the first to take advantage of the new opportunities.

But the approach taken by the airlines varied widely, from extremely conservative additions to wildly over-ambitious route expansions. And many carriers had similar ideas for expansion, with Florida, Texas and Arizona being the most popular destinations for new service.

Western Airlines was probably the most conservative trunk carrier in the country. They were the last of the trunks to introduce pure jet service in 1960, and also the last to offer widebody service, finally introducing the DC-10 in 1973. It was one of the few not to order the Boeing 747.

So it should come as no surprise that the airline did not jump headlong into the uncharted waters of the deregulated environment. While most carriers promoted the start of some new services by early 1979, Western took a more measured approach. By the end of 1979, Milwaukee, Spokane and Washington D.C. had all been added from the airline’s traditional eastern terminus in Minneapolis/St. Paul. This meant Western had become a transcontinental carrier, offering direct (2 stop) service between the East Coast and Seattle.

Another carrier to move with caution was Continental Airlines. By the December 15, timetable, Continental was promoting service from Washington/Dulles to Houston (starting January 2, 1979). Continental also joined the transcontinental ranks, with direct service from Dulles to Los Angeles (albeit with 4 stops).

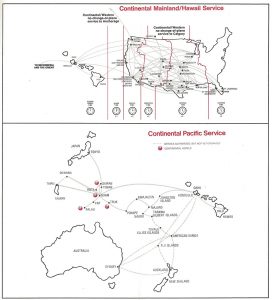

By the end of 1979, Continental had added routes to New York City, as well as to Western Mexico. Additionally, long-delayed service from Hawaii to the South Pacific had also been inaugurated.

Pan Am’s many attempts over the years to acquire a domestic airline to feed its globe-spanning international network had largely been thwarted by other carriers claiming that such a combination would provide an unsurmountable advantage over other airlines, many of which had little or no international routes. Deregulation provided the opportunity for Pan Am to build its own domestic network, but given the fact that the carrier’s fleet was primarily built for long-haul intercontinental services (with the exception of the 727 fleet working the Internal German Services), acquisition was seen as the most viable path to that end, rather than individual route acquisitions. In the meantime, the carrier’s timetable dated October 28, 1979, does show a few domestic segments added, namely connecting New York with Miami and San Francisco.

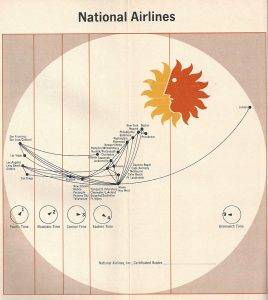

National Airlines was focused on expanding its footprint in the trans-Atlantic market, and only made a few tentative moves in the domestic arena. The March 3, 1979 timetable shows that Seattle was added with a route to Houston, with service to Los Angeles forthcoming on April 1. Also on that date, National started operating between Miami and San Juan with 3 daily round trips.

The fact that National attracted interest as a takeover target may have also resulted in a more conservative strategy, given the bidding war that ensued. The airline’s services remained essentially unchanged for the remainder of the year, as illustrated by the (condensed) route map on their September 5, 1979 timetable.

TWA’s initial route additions were also relatively meek, as the January 9, 1979 timetable shows new service between St. Louis and Minneapolis/St. Paul, and from Palm Springs to Phoenix, continuing to Chicago. (At this point, Chicago was still considered TWA’s primary domestic hub. It would be a few years before TWA would decide that they couldn’t compete with the likes of American and United at O’Hare.)

However, by the end of 1979, TWA had added routes from a number of new cities to St. Louis, and had also greatly expanded its footprint in Florida. As the December 15, 1979 issue illustrates, 3 new Florida destinations were added, and service to Florida was inaugurated from 7 cities in the northeastern US; Boston, Cincinnati, Columbus, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, New York and Washington. While TWA operated 37 weekly flights to Florida in the winter of 1978/79, by the following winter, that number had risen to 276!

Eastern Airlines enjoyed a number of new route awards prior to the passage of the Airline Deregulation Act, and the timetable dated September 6, 1978 shows the carrier focused on bolstering its strongest markets, Atlanta, Miami, New York and San Juan. The December 13, 1978 issue, which was the first after Deregulation, shows a similar strategy, although with an increasing emphasis on secondary markets in Houston, Central Florida and St. Louis (which was becoming an east-west hub).

By the end of 1979, Eastern had tied Albuquerque, Phoenix and Tucson to its primary hub in Atlanta, and added Reno to St. Louis service. However, the Los Angeles to Orlando service started the prior winter had disappeared from the schedule.

Delta Air Lines’ timetable dated December 15, 1978 shows a rather conservative strategy as it inaugurated only 5 new routes, all of which were tied to a station where the carrier already had a significant presence. DC-8-50s, which were on the verge of being phased out of the fleet, provided some of the capacity required to operate the additional flights.

The timetable from the end of the following year, dated December 15, 1979, shows Delta still operating all of those routes, with the Atlanta services up to 4-5 daily flights. The carrier had also added routes to the West from both Atlanta and Dallas/Ft. Worth.

Northwest Orient Airlines added 3 new cities to its network with the timetable dated February 1, 1979, Orlando, St. Louis and Las Vegas. St. Louis was connected to Chicago and Minneapolis/St. Paul, which were 2 of Northwest’s largest stations. Orlando received service from Boston and Philadelphia (as did several other Florida cities).

But Las Vegas was something of a head-scratcher, with once daily service to San Francisco that continued to Minneapolis/St. Paul. San Francisco was a minor station for Northwest with only 4 other daily flights, and the direct service to Minneapolis took more than twice as long as Western’s nonstop service. As illustrated by the timetable dated December 18, 1979, service to Phoenix had also been inaugurated.

American Airlines took a more aggressive approach than most, and the timetable dated January 20, 1979 shows 9 new cities being added to its network. Most of the new stations were tied into major hubs, either with nonstop or direct service. Service was added connecting Dallas/Ft. Worth to Albuquerque, Miami, New Orleans, Reno and Tampa, while Chicago received service to Minneapolis/St. Paul.

A few new routes didn’t feed major hubs, as service was inaugurated to Las Vegas from Cleveland and Detroit, while the oddest of all was a trans-continental nonstop service from San Francisco to Miami. Unsurprisingly, the San Francisco/Miami service was already discontinued by the end of year.

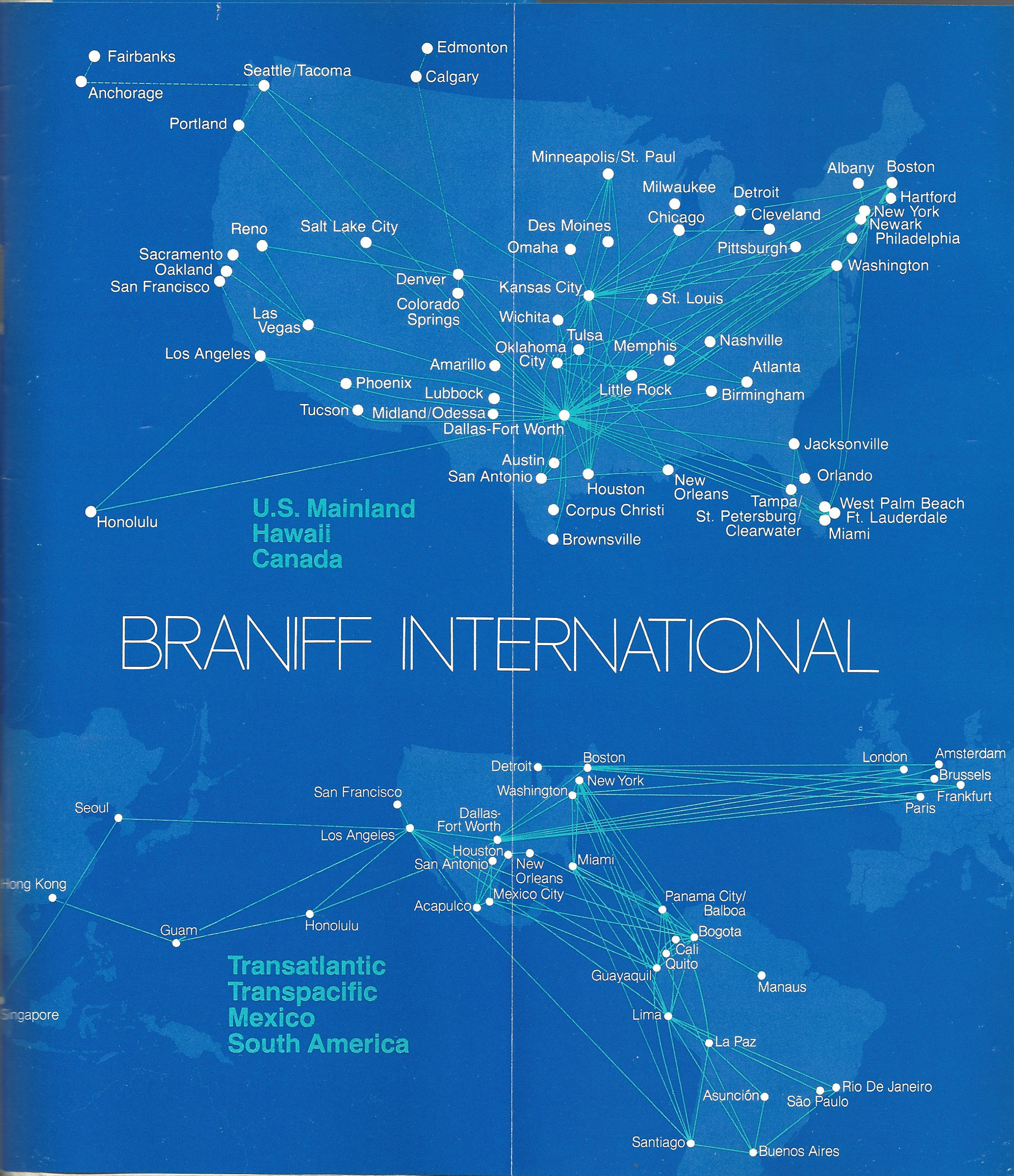

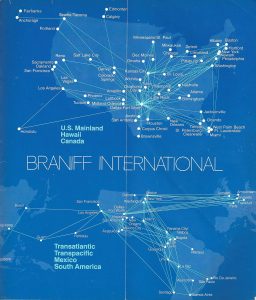

But the biggest eye-opener in the Deregulation route frenzy was Braniff International Airways, which inaugurated new service on 32 routes and opened 15 new stations with its December 15, 1978 timetable. The centerfold of this issue boasts about the new service, and claims, “to begin service to so many cities at one time is unprecedented in the history of air transportation”. (The map in the centerfold identifies Los Angeles as a new station, even though international service had been offered there for years.)

Braniff was right about its expansion being “unprecedented“. These new route requests came with a “use it or lose it” condition, and as one of the smaller trunk carriers, Braniff’s fleet was stretched thin attempting to cover 64 additional segments.

Rather than pause and allow all of this growth to be properly assimilated into the system, Braniff continued to expand in 1979, both domestically (and more importantly) internationally. The all-727 domestic fleet could not handle all of the new flights so DC-8s soon started operating domestic segments. By summer, DC-8s were operating scheduled services to stations such as Denver, Memphis, Tampa and Orlando. (The carrier would later be fined by the FAA for many hundreds of maintenance violations resulting from the demands placed on the fleet.)

Braniff ordered dozens of aircraft to support the new services, added through Concorde service from Dallas/Ft. Worth to both London and Paris (in cooperation with British Airways and Air France), created a trans-Atlantic hub in Boston (one of the cities added in December, 1978), and began operating trans-Pacific services as well. The results were predictable, and the once profitable carrier quickly faced mounting losses and declining customer service.

Routes and employees were shed rapidly but the airline had already become a poster child for those who argued that some carriers wouldn’t know how to survive in a deregulated environment. Although Braniff lasted until the spring of 1982, the foundation for its demise was laid within the first year of Deregulation.

Next: smaller airlines navigate the first year of Deregulation.

Written by David Keller

This October marked the 40th anniversary of the Airline Deregulation Act, which was signed into law by President Jimmy Carter on October 24, 1978. The newly-signed legislation would bring a seismic change for US airlines, and would forever alter the course of air transportation.

This article is the first of a series focusing on the impact of Deregulation on the airline industry, which had been molded by the prior 40 years of regulation.

The primary government agency responsible for regulating the airlines was the Civil Aeronautics Authority (CAA) which was created in 1938. In 1940, some of the responsibilities of the CAA were split off to form a new agency, the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB). Amongst the tasks delegated to the CAB were accident investigation, and approval of fares and routes.

The goal was to create an environment that was conducive to growth of the commercial aviation industry, both by limiting the amount of competition each operator would face and by reducing aircraft accidents. This meant CAB had to balance competing directives, one to ensure competition (to prevent monopolies), and the other to limit it so airlines could operate profitably.

While accident investigations would later be turned over to the FAA (Federal Aviation Administration), the fare and route approvals would remain in the jurisdiction of the CAB. This meant that many of the important decisions affecting the growth and financial well-being of the airlines were largely in of the hands of the CAB rather than the airlines themselves.

One of the main tenants of route requests was that the requesting carrier had to show that additional competition on a given route was in the public interest. Requests to serve new routes became cases, which were subject to delays of months or years, as well as appeals by carriers hoping to limit competition on their money-making routes.

Besides attempting to promote just the right amount of competition, the CAB also made awards with an eye towards keeping individual airlines financially viable. At the conclusion of World War II, there were 15 domestic trunk carriers (not including Pan Am, which was not allowed to operate domestic services). While some of these airlines had assembled far-reaching route networks connecting larger cities over long distances, others were geographically challenged, operating short segments in a small area.

Realizing that this would make it difficult for such carriers in the long term, the CAB granted them longer routes to expand beyond their traditional regions.

Colonial Airlines was one such airline, and in the mid-1940s was operating a route system roughly bounded by Washington, D.C., New York City and Montreal. In 1946 the carrier was given authority to serve Bermuda from both New York and Washington, D.C. to bolster its financial position.

Not having aircraft capable of providing such service delayed the start until the following year, but a few prime routes were not enough to reach a large enough scale to remain consistently profitable. The illustrated timetable dated April 29, 1956 shows the carrier’s limited route system, despite the Bermuda services. This was also the final timetable issued by Colonial, as it was merged into Eastern Air Lines on June 1st of that year.

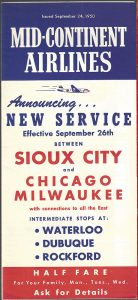

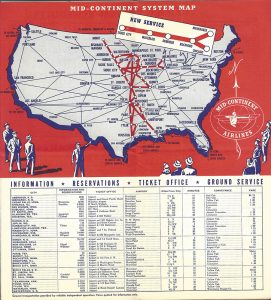

Another small trunk line, Mid-Continent Airlines, operated a limited system between Minneapolis/St. Paul and Tulsa, as depicted on the cover of the January 10, 1945 timetable. In 1947, the carrier received route extensions to the Gulf Coast, adding Houston and New Orleans to its system. The timetable dated September 24, 1950 shows additional service, this time in the form of an east-west service from Sioux City to Chicago and Milwaukee. (It appears that a separate aircraft operated one of the eastbound legs from Rockford, allowing “through” service from a single inbound destination to both Chicago and Milwaukee.)

This was another case in which the new routes weren’t enough to stave off the inevitable. In 1952, Mid-Continent was acquired by Braniff International Airways, which also lacked an extensive domestic network.

However, Braniff did have international service to South America and a route system that combined well with Mid-Continent’s. As the route map from the Braniff timetable dated September, 1952 illustrates, the 2 systems dovetailed quite nicely.

In the early 1940s, National Airlines operated a route system that snaked its way from New Orleans to Miami, as evidenced by the route map from the July 1, 1941 timetable. While a number of routes were awarded after the conclusion of the war, National was given authority to compete with Eastern Air Lines on the lucrative New York to Florida run in 1944.

The route map from the timetable dated October, 1946 shows the impact of the new services on National’s network. Although the map also includes Havana routes, that service was not yet being offered.

The new routes saved National from probable bankruptcy, and with the later addition of routes between Florida and the West Coast, kept the carrier in operation until a merger with Pan Am in 1979.

Although not in as dire a predicament as the aforementioned Colonial Airlines, Northeast Airlines also found itself with a route system wedged largely between New York City and Montreal. However, having operating rights on the busy Boston to New York route was certainly a difference maker, and the timetable dated September 28, 1947 shows 10 round trips being offered.

Northeast was not a recipient of long haul services immediately following the war, but did find that being confined to a small area was limiting its ability to compete with larger airlines. In 1957 Northeast began service between New York and Florida, in competition with Eastern and National. Despite many lines on the route map from the June 1, 1957 timetable connecting Florida with the northeast, the only route being operated at the time was between New York and Miami.

Continental Air Lines developed route system in the south central US, largely serving cities in Colorado, New Mexico, Kansas, Oklahoma and Texas. As illustrated by the route map from the timetable dated April 1, 1955, Continental had acquired local service carrier Pioneer Air Lines. Although this did add Dallas/Ft. Worth to the network, it also added many short segments to stations providing small numbers of passengers.

However, later that same year, Continental was awarded a route connecting Los Angeles and Chicago (via Denver and Kansas City), despite having no presence in either end of the route. Service began in 1957, once suitable equipment had been acquired. In this case, the route award gave the airline a huge expansion of its area of influence, and Continental steadily filled in the map with routes connecting those new cities to its traditional network.

By 1964, Continental had moved its corporate headquarters from Denver to Los Angeles. The route map from the October 1, 1978 timetable shows how Chicago and Los Angeles had been incorporated into the route system. It also shows later route expansion to Florida, Hawaii and the Pacific Northwest.

Another example of the CAB’s impact on American aviation was the creation of feeder, or local service, airlines. This was an attempt to bring air service to still more cities than were part of the trunk airlines’ route network. These airlines required “public service” subsidies to remain financially viable, given the nature of their stated mission.

Another example of the CAB’s impact on American aviation was the creation of feeder, or local service, airlines. This was an attempt to bring air service to still more cities than were part of the trunk airlines’ route network. These airlines required “public service” subsidies to remain financially viable, given the nature of their stated mission.

Over 2 dozen local airlines received certificates to start service, but some never left the ground, and others failed after a short period of operation or were merged into other carriers.

Parks Air Lines was one of those local carriers that failed to launch. The airline issued several timetables in the summer of 1950, including the illustrated August 1, 1950 issue. But the company was unable to get started and its routes were awarded to Ozark Air Lines and Mid-Continent Airlines. (In fact, the new Mid-Continent routes to Chicago and Milwaukee previously mentioned were originally intended to be operated by Parks.)

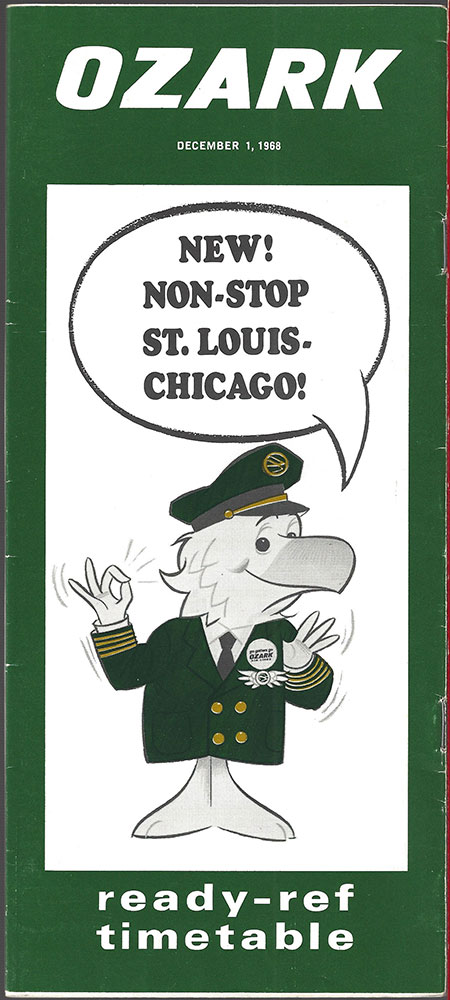

Ozark Air Lines inaugurated service on September 26, 1950. As the timetable from that date illustrates, the flight numbers, times, and even local phone numbers were unchanged from those in the Parks timetable.

By 1956, just over 1 dozen local service airlines remained. Besides opening service to new cities, these carriers also inherited services that the trunk carriers wished to shed so they could retire their DC-3s and concentrate on more profitable routes.

As these airlines grew, they began to explore acquisition of aircraft larger than the DC-3, which made of the vast majority of the combined local airline fleet in the mid-to-late 1950s. The CAB was not particularly fond of this idea, as larger aircraft would require additional subsidies to operate profitably on routes that were largely low density.

Despite this, several airlines did acquire larger equipment beginning in the mid-1950s. As this now gave those carriers equipment that was more on par with the larger airlines, they felt prepared to operate routes that had profit-making potential. This did have an appeal to the CAB (and government in general), since subsidies (although rather modest in dollar amount) were always a hot button political issue. Convairs, Martins and F27s were incorporated the various airlines’ fleets by the early 1960’s.

However, while the locals added those types, the trunks were busily reequipping with pure jets, which still left the locals behind in the technology curve. But with the introduction of “small” jets in the mid-1960s, the locals were able to make a sound case to compete on routes previously in the domain of the trunk carriers.

BAC 1-11s, DC-9s and 737s provided the ability to both operate from shorter runways than the first generation 4-engine jetliners, and also to make a profit on short route segments. The locals placed orders, and all (with the exception Lake Central) were operating jets by the end of 1967. With the prospect of local carriers truly being able to compete on profitable routes, coupled with the opportunity for those services to reduce subsidies required, those airlines finally began to receive such route authorization.

In the late 1960s and early 70s, the CAB awarded numerous routes the local carriers, which were eager to show off their shiny new jets, and shed their “puddle jumper” image. And as the routes came, so did orders for additional jets.

Generally, these awards were a combination of new nonstop authority between cities already served by the carrier, and new routes outside of their traditional service area.

The Allegheny Airlines timetable dated April 27, 1969 promotes new services to Nashville and Memphis from Philadelphia. (Both of those cities had recently been added to the system with service to Pittsburgh.) In addition to these new cities, Allegheny was operating non-stops from Pittsburgh to points already in the network, such as New York City, Boston, and Louisville.

Frontier Airlines didn’t wait for the twin engine jetliners, as the carrier placed an order for the trijet 727. The timetable dated July 7, 1969 shows the airline operating jets (which were a mix of 727s and 737’s at that point), on a number of nonstop routes from Denver. Service was offered to Las Vegas (a new station), as well as Dallas, Kansas City, Phoenix, St. Louis and Salt Lake City.

The two illustrated North Central Airlines timetables, from June 15, 1969 and January 1, 1970 show the inauguration of service to a new destination, Denver, as well as between the airline’s 2 largest stations, Minneapolis/St. Paul and Chicago. North Central would soon receive additional authority to operate from Milwaukee to both New York and several Ohio cities, further expanding the network.

Ozark Air Lines received similar routes, as promoted on the covers of timetables dated December 1, 1968 and October 1, 1969. The 1968 issue touts service between the carrier’s 2 largest stations, Chicago and St. Louis, while the 1969 timetable features a clean-shaven George Carlin hawking new nonstop service from St. Louis to Dallas/Ft. Worth. By this time, Ozark had already received new authority to serve some of the most popular destinations for new service, Denver, New York City, and Washington, D.C..

Southern Airways’ timetables dated October 27, 1968 and January 1, 1970 show that most of this carrier’s new nonstop authority was to serve cities outside of its local service area. The 1968 issue promotes new service to Washington, D.C. and New York City from Columbus, Georgia, Dothan, Alabama and Eglin AFB in Florida, thus eliminating the need to connect in Atlanta. The route map of the 1970 timetable shows service had already been started to St. Louis, with Chicago and Florida routes beginning shortly. (Florida was one of the few areas in the country that didn’t have a local service operator providing service throughout the state.)

In Trans-Texas Airways’ timetable dated July 1, 1966, the airline was operating primarily to cities in Texas and bordering states. A number of the routes in West Texas and New Mexico were being operated by Continental a decade prior.

By the summer of 1970, the route map sported routes to Denver, Salt Lake City, Los Angeles and Mexico. To capitalize on its expanded presence, TTA had changed its name to Texas International Airlines the previous year.

Some of the CAB’s attempts to strengthen weaker airlines were questionable at best. On October 1, 1969, National Airlines began service between San Francisco and Atlanta. One look at the route map, and it’s difficult to see how this was going to pan out, even in the relatively tame competitive environment of the day.

National started with 2 roundtrips on the route, then pared it back to 1 the following year. It appears the service was suspended in the mid-1970s, with the single roundtrip returning in the summer of 1976. By late 1976 the operation was twice weekly, which then dropped to a single weekly frequency. (In addition to needing CAB approval to start new service, there were also rules on ending service. An airline wanting to discontinue a route would sometimes reduce the frequency to only 1 per week as they petitioned to stop service altogether.)

In another attempt to assist the oft-ailing Northeast Airlines, the carrier was awarded the highly coveted Miami to Los Angeles route, also with an October 1, 1969 start. Once again, the route map reveals this to be a questionable decision, although perhaps not as much as the fact that Northeast’s longest range type was the 727-100, which was not designed for transcontinental service. The airline did have Lockheed L1011s on order, which could certainly make that journey, although the ability to pay for them was in serious doubt.

Northeast was evidently confident of their ability to turn a profit on the route, and started service with 3 daily roundtrips. That was reduced to 2 by early 1971, and a single roundtrip a few months later. Northeast finally found its badly-needed merger partner in the form of Delta Air Lines the following year, but Delta did not receive the Miami-Los Angeles route as part of the merger. The route showed up on Delta’s route maps for several years as “Subject to CAB approval”, and was eventually awarded to Western Airlines in 1976.

One of the last major route cases the CAB handled was finalized in the summer of 1977 and involved service between Denver and the Southeast. Incredibly, until late July of 1977, it was not possible to fly nonstop between Denver and Atlanta, which even then were 2 of the largest hubs in the US. The only through service was a long-running Eastern-Braniff interchange service which operated 4 daily services via Memphis.

The CAB designated Delta and Braniff to receive nonstop authority on the route. Delta was a natural fit, given its strength in Atlanta, but Braniff was not a major player in either market. Both carriers started service on July 28, 1977 with 4 daily non-stops. This brought an immediate termination of the interchange service through Memphis.

Eastern attempted to maintain the 4 daily frequencies on the Memphis-Atlanta segment (which was its only route from Memphis), but very quickly ceded the market to Delta, which had a sizeable operation there. The September 6, 1978 shows only a single weekly frequency on the route and by the December 13, 1978 issue, service was terminated, leaving Memphis as an unnamed point on the route map,

Braniff was struggling with the new route even before Deregulation, cutting back on frequencies, while Delta added new ones. By late 1979, Braniff was down to a single nonstop plus several one-stop flights, and in October the route was dropped altogether along with many others as Braniff had put itself into a dire financial situation. The other half of the old interchange service, Eastern Airlines, filled the void, starting flights in December with 4 daily non-stops.

As mentioned, the CAB also approved fares the airlines could charge for each level of service. Essentially, the fare for a given service (First Class, Coach, etc.) was the same on a specific route regardless of which airline was offering the service. Continental Airlines has an explanation of this concept in the gatefold of their timetable dated June 30, 1966.

For those who don’t remember pre-deregulation days, it’s probably difficult to grasp that average load factors in the 1960s and 70s were generally in the low to mid 50 percent range. Fares were set such that airlines only needed to fill just over half of their seats to make a profit, sometimes even less.

As detailed in the annual reports of National Airlines and Texas International Airlines, it was not unusual for airlines to transport more cold seats that warm ones over the course of an entire year. National’s chart from their 1975 annual report shows their annual load factor exceeding 50% in only 2 of the 5 years encompassing 1971 through 1975. For one of those years, 1971, the load factor was approximately 40%.

Texas International Airlines’ 1969 statistics illustrate that they never exceeded a 50% load factor during the 1960s, and early in the decade, those load factors were actually in the upper 30s. Being a local service carrier, much of the lack of revenue from paying passengers was covered by federal subsidies.

This meant that the airline industry, having fare levels set to ensure profits with half empty planes, and being generally protected from unbridled competition, were not the lean and mean organizations they would need to be in order to prosper in a deregulated environment.

The US airline industry arrived at the transition between a regulated industry and a deregulated one with 11 trunk carriers, 8 local service carriers, a few small airlines in Alaska and Hawaii, a number commuter lines, and intrastate carriers in several states (which were not regulated by the CAB as long as they only served destinations within a single state).

Some airlines were confident in their ability to thrive in a deregulated environment and wholeheartedly supported the Act’s passage. Others, shackled with high costs and fearing additional competition siphoning profits, were opposed, while some airlines had mixed feelings.

Regardless of each airline’s opinion on the matter, they were all thrust into the brave new world on October 24, 1978.

Written by Lester Anderson

Hindsight is often depressing. I was a commercial aviation enthusiast during my junior high/high school/college years of the 1960’s. During that time friends and I would visit airports and get timetables from the ticket counters, and we were on the mailing list of all the major carriers. But they were tools to see what airplanes we could see, and maybe which ones on which we could get an inexpensive flight. I certainly did not think of them as pieces of history to keep.

Oh, do I regret that I threw away all those Braniff, Northeast, Eastern, Northwest Orient, TWA, Mohawk, Allegheny, Continental, and United timetables. But today’s newspaper does not seem like it is history; you need to wait years, and have the foresight, to preserve these artifacts. Sadly I did not.

But this was the time when jets took over the transcontinental travel (certainly the nonstop travel). There were a few propeller trips left (Northwest had an overnight “freighter” flight on a DC7C that was less expensive than day flights but made a long stop mid route).

Being fascinated with something that did not exist anymore, I wrote to United Airlines asking if they had any old timetables. I was fortunate that someone kind in marketing helped my aviation enthusiasm and sent me a few timetables from the 1946 to 1958 time period. I wish I knew his (or her) name. I am ever grateful because they did preserve a bit of airline history with me and I would like to share some of that wealth of history with you.

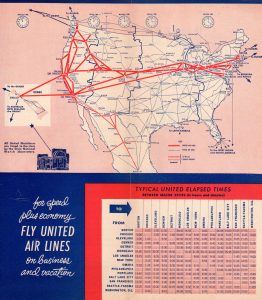

In 1946 United flew coast to coast with their ‘Mainliner 180’ (DC-3) and ‘Mainliner 230’ (DC-4) airplanes.

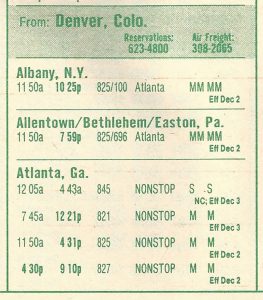

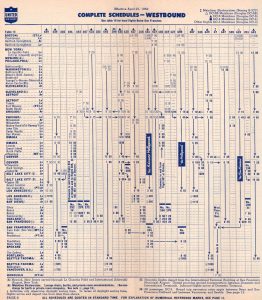

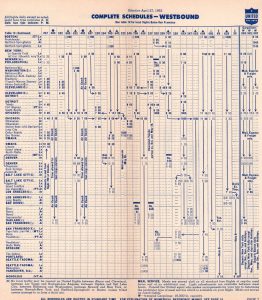

Here is the Westbound schedule for April/May 1946 (15 months before I was born)

Note flight 1 (used by many airlines as their signature flight). It is a DC-3 flight with many stops from New York to San Francisco. Note the small 1 in a circle. That indicates when a meal is served onboard. Then compare it to Flight 3 on the next page, which is a DC-4 and makes stops in Chicago and Denver on the way From New York to San Francisco.

Timetables were also a great marketing tool for airlines. In 1946 United promoted its ‘Air Freight’ services. Reading the description, you can see that 25 pounds from Chicago to San Francisco costs less than a Priority Mail letter does today.

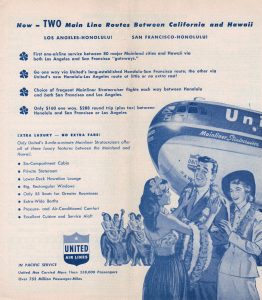

But timetable ads focused on passengers soon followed, as in these two 1950 ads that featured the pinnacle of luxury, the Boeing 377 Stratocruiser, flying between California and Hawaii.

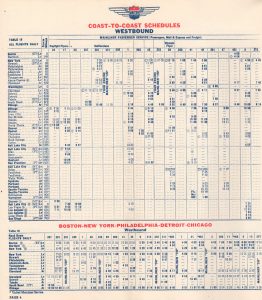

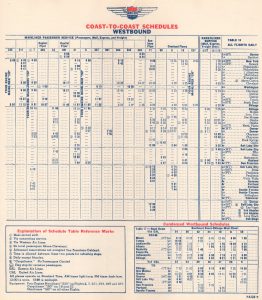

In 1952 the service expanded and got faster with transcontinental DC-4, DC-6 and DC-6B flights.

And the note on the bottom of the timetable page is a reminder that while an airplane may fly between two cities and carry through passengers, it does not mean the CAB has given route permission for carrying passengers between just those two cities. But the route map grows and the times between cities decrease.

Ads in the timetables were getting to be more what we are used to in airline ads — vacation spots to exotic places, and new airplanes with “more seats and more service”.

Then the last of propeller plane services, DC7 Red Carpet Service, is described in the following December 1958 timetable. Note that not only is a meal service offered, they tell you what you are getting (i.e. Lunch and Snack). The route map has been expanded, and you can see the flight times have shortened compared to 1952.

Flight 703 is a nonstop coast to coast flight New York to San Francisco. Other airports did have DC-7 service, but the flights connected in Chicago (something I did a lot flying United in the 80’s and 90’s).

And looking at the flying time of 8 hours and 45 minutes for a New York to San Francisco flight—think of today. The flying time today is shorter, but between the car-park, monorail/bus to the terminal, security check and then the monorail/bus to the car rental facility—is it really any faster? And you did get Lunch and a Snack in those days!

I hope you enjoyed this trip back in time.

Lester Anderson

By David Keller

email: dkeller@airlinetimetables.com

facebook: facebook.com/airlinetimetables.comllc

website: http://airlinetimetables.com

blog: http://airlinetimetableblog.blogspot.com

______________________________________

May of 2017 marked the 65th anniversary of something we have long taken for granted, jet-powered air transportation. As much as air travel shrank the globe by cutting transit times from weeks (or months) to days, jets have further reduced those days to mere hours.

On May 2, 1952, the era of jet powered airline service began when a BOAC de Havilland Comet lifted off from London Airport enroute to Johannesburg via Rome, Beirut, Khartoum, Entebbe and Livingstone. The May 1, 1952 timetable shows this initial service, which arrived in Johannesburg on Saturday afternoon, departing on the return Monday morning.

As the world’s first jet transport, the Comet was trailblazer, operating at speeds and altitudes not attainable by propeller-driven aircraft of the day. As additional aircraft were delivered, design flaws began to take a toll, and in less than 2 years, 5 aircraft had been lost in accidents. The most devastating flaw was metal fatigue, which after only a few thousand cycles made the aircraft susceptible to explosive decompression while in flight.

The Comet would never recover its reputation after being grounded in 1954, despite the creation of a much-improved version in the late 1950’s. Comets returned to airline service in 1958 in the form of the Comet 4, but by then, superior models from Boeing and Douglas Aircraft were on the horizon, and only 76 Comet 4s were delivered.

The next jet transport to enter service was the Soviet Union’s Tupolev 104. This type had a design similarity with the Comet, in that the engines were placed inside the wing, near the fuselage. US manufacturers eschewed this engine placement in favor of suspending them from the wings on pylons, which reduced the likelihood of structural failure in the event of a fire, and I would imagine made them more accessible for maintenance.

Several hundred TU-104’s were built, with the type remaining in service with Aeroflot for roughly 30 years.

While these and other early jet transports played a role in the technological advances of commercial aviation, it was largely the US-built types that led to the rapid expansion of jet service across the globe. This article will highlight the jet service inaugurals of US trunk carriers, which all occurred in just over 2 years, as those companies raced to join the Jet Age.

The aircraft widely considered to be the first successful jet transport was Boeing’s model 707. On October 28, 1958, Pan Am inaugurated 707 service, putting the type to work on the New York – Paris route. The timetable from this date has an image of the 707 wings and engines on the carrier’s traditional blue cover.

The gatefold has an ad promoting 707 service to Paris and Rome, with London starting a few weeks later. (In the timetable itself, it becomes evident that the continuing service from Paris to Rome was actually operated by a DC-6.) While most of the transatlantic services in this timetable were being operated by DC-7’s, the arrival of the Boeings meant the days of the Douglas piston types were numbered.

In December of 1958, National Airlines scored a coup by placing leased Pan Am 707s in service between New York and Miami, thus claiming the title of the first airline to offer domestic jet service in the United States. 707 flights were inaugurated on December 10, 1959, and the timetable dated December 14, 1959 shows 2 round trips being operated (one of which became effective on December 16th)

Flight timings meant that 2 different aircraft were required on any given day. But no 707’s were painted in National colors which likely means the aircraft were “wet-leased” and the actual ships on the Florida run varied from day to day.

In January, 1959, American Airlines inaugurated transcontinental 707 service. Further info and timetable scans were included in the previous Captain’s Log issue from earlier this year, so be sure to check out the article on American Airlines.

TWA was next with jets, also using them on transcontinental routes beginning in March of 1959. The timetable dated April 26, 1959 shows on the 707’s engines (which seemed to be popular subject matter for timetable covers), and advertises service between New York and Los Angeles/San Francisco, as well as between Chicago and Los Angeles.

Interestingly, the back cover of this timetable advertises Los Angeles to New York flight times as 4 hours and 55 minutes, while American inaugurated this route boasting of a 4 ½ hour flight time only a few months earlier. It seemed odd that TWA would be willing to concede a significant speed differential to its rival, particularly given the atmosphere of one-upmanship that prevailed as additional airlines acquired their first jets. However, a check of American’s timetable for the same date shows that the advertised flight time from Los Angeles to New York was also 4 hours, 55 minutes. Part of this would have been attributed to the slowing of the Jetstream winds from winter to spring, but it also appears that the additional fuel burn required to maintain those very high cruise speeds was not worth the few minutes saved.

Continental Airlines’ April 26, 1959 timetable shows their initial 707 schedules, slated to begin on June 8th. A single round trip was operated between Los Angeles and Chicago, with 2 additional round trips being added on June 22nd. As with the previous airlines, Continental’s 707s were -120 models sporting non-fan engines. Not requiring transcontinental range, Continental would later opt for a fleet of medium range 720B fanjets that served until the mid-1970’s.

On this same date, April 26, 1959, the Sud Aviation Caravelle also entered service, with SAS being the first airline to operate the twinjet. The Caravelle was used primarily in Europe, although United Air Lines did order 20 aircraft, putting them into service in July, 1961. As the timetable dated February 1, 1963 shows, United used the Caravelle largely on the former Capital Airlines routes, from the East Coast as far west as Minneapolis/St. Paul, and along the eastern seaboard, as far south as Miami.

Almost a year after the 707’s entry into service, its primary competitor, the Douglas DC-8 began scheduled flights. As advertised on Delta Air Lines’ September 1, 1959 timetable, the carrier started DC-8 service on the 18th of that month. Two round trips between Idlewild Airport in New York and Atlanta were initially operated, with the aircraft overnighting on the East Coast. In mid-October, an aircraft originating in Miami began nonstop service to both Chicago and Atlanta.

In a virtually simultaneous entry into service, United Air Lines also put the DC-8 to work on September 18th, operating between San Francisco and New York. Owing to the fact that United’s first jet service departed from the West Coast, Delta’s initial departure was several hours ahead of United’s. Both airlines were operating series -10’s, most of which were upgraded to -20’s or fanjet-powered -50’s shortly thereafter.

Already having been upstaged by National Airlines on the New York – Miami route the previous winter, Northeast Airlines leased a Boeing 707-320 series aircraft from TWA for the 1959 Winter season. The December 1, 1959 timetable shows a single roundtrip beginning December 17th, which was operated 6 times weekly, with no service on Tuesday.

In late 1959, Braniff International Airways placed its “Different and Superior Boeing 707-227”s into service. The 707-220 model combined the fuselage of the -120 with the larger wings and more powerful engines offered on the -320 series. Braniff was the only customer, ordering 5 examples.

The first, N7071, crashed during flight testing prior to delivery, although that registration appeared on the carrier’s artwork for several years afterwards. The remaining 4 aircraft were delivered and served over a decade with Braniff before being traded to BWIA for 727s in the early 1970’s. Braniff had something of a penchant for oddball models of the 707, as they also acquired 4 short-bodied 707-138Bs from Qantas in the late 1960s.

Eastern Airlines’ January 24, 1960 timetable shows the carrier’s initial jet service on what was obviously one of the most hotly contested markets in the nation, New York to Miami. Being a bit late to the party, 4 roundtrips were being offered, with 2 more being added in February. Eastern’s DC-8’s were delivered as -20s, initially referred to by the airline as DC-8Bs, sticking with the nomenclature used for Douglas’ piston transports.

Another airline to start service with DC-8-20 series aircraft in 1960 was National Airlines. The carrier’s April 24, 1960 timetable shows the discontinuance of 707 services as of April 25th, with the DC-8’s assuming the pure jet duties. Flight segments between New York and Florida were scheduled for 10-20 minutes less with the Eights than with the Boeings.

The third player in the competition amongst US companies to build jet airliners was General Dynamics. The company had purchased Convair in the 1950’s, and attempted to win a significant portion of the market by offering aircraft that were faster than the Boeing or Douglas types.

Delta Air Lines placed the Convair 880 into operation in May, 1960. As the timetable dated April 24, 1960 advertises, initial services were from New York to Atlanta, Houston and New Orleans. (The flight to Houston was scheduled to require 28 less minutes than the DC-8 previously used on the route.)

Additionally, Delta put the 880 into service with all “Deluxe First Class” seating, and utilized a special paint scheme that appeared on no other aircraft type. In less than 2 years, the Convairs were converted to a 2 class seating configuration, and they would eventually be repainted in the “widget” colors that were being applied to the entire fleet.

General Dynamic’s gamble with the Convair 880 (including further development into the model 990) did not pay off. The company had difficulty meeting performance guarantees, and the lower seating capacity and high fuel burn required for high cruise speeds resulted in just over 100 aircraft being built.

Western Airlines entry into the Jet Age came in the form of 2 707-120s which had originally been ordered by Cubana. These aircraft were leased to Western and entered service in the Summer of 1960. The June 1, 1960 timetable shows these aircraft operating 3 round trips between Los Angeles and Seattle, some via San Francisco or Portland.

As was the case with Continental Airlines, Western did not need the 707’s range, instead purchasing the smaller 720B. The 707s remained in the fleet for about 2 years, returning to Boeing as the 720Bs were delivered.

Bring up the rear of the pack was Northwest Orient Airlines, which started operating DC-8Cs (DC-8-30s) “to the Orient”. The July 1, 1960 timetable shows DC-8 service beginning on July 8th, primarily on flights between the US and Asia, thus requiring the longest range version of the aircraft available at the time.

Despite having been a loyal Douglas customer for many years, Northwest soured on the Eight, selling the entire fleet just a few years later as 707-320Bs from Boeing took over the TransPacific services. Northwest would not return to the DC- line until the DC-10 joined their fleet about 10 years later.

In 1961, TWA initiated Convair 880 service, on its way to becoming the type’s largest operator. The February 1, 1961 timetable shows 880s serving medium range routes to 8 cities. With the imposition of fuel quotas in 1974 that resulted from the Arab Oil Embargo of the previous year, there could no longer be any justification for retaining the fuel-guzzling jets, and TWA retired the fleet by the summer of 1974.

Although not the first jet in the fleet of any US trunk carrier, the Boeing 720 was notable for the number of those airlines it flew for. Boeing was able to create a slightly smaller, lighter version of the 707, albeit with a high degree of commonality between the two. (In fact, several airlines did not distinguish between 707s and 720s when specifying equipment in their timetables.) Every trunk airline that purchased 707s also operated 720s at some point (either purchased or leased), and given Douglas’ lack of an equivalent aircraft, 720s were also operated by United and Eastern, each having substantial DC-8 fleets.

The July 1, 1961 Northwest Orient Airlines timetable shows the 720B entering the fleet with service from Minneapolis/St. Paul to Chicago, Milwaukee and New York. This paved the way for the 707s to take over the Asian services from the DC-8s, and it is my understanding that 720s were used to Asia on an interim basis until there were enough 707s available to operate the full schedule.

Despite being very popular in the early 60s, most of the trunks were quick to dispose of the 720Bs, phasing them out in the late 60s or early 70s, while keeping their 707s or DC-8s. Western Airlines was the primary exception, maintaining 720 service until the late 1970’s.

It is worthy to note that all of the 720 operators ordered large numbers of Boeing aircraft that was more suitable for medium range flights, the 727. In fact Eastern and United were 2 of the first customers.

65 years on, and some things remain largely the same. Fuselages are still long, roughly cylindrical compartments with passengers above, luggage and cargo below, a cockpit at the front and a tail at the rear. Most types still have jet engines suspended below the wings on pylons. Despite a trend from the 1960s to the 90s for rear- and/or tail-mounted engines, most of those are out of production and the vast majority of jets being built today have wing-mounted engines.

And yet, things are very different as well. Jet aircraft are much quieter, and no longer leave black exhaust trails to mark their passing. While 4 engines were pretty much a requirement in the early days (particularly for overwater flights), they are a liability in today’s environment. Boeing and Airbus struggle to find buyers for their 747 and A380 models, while pushing twin engine aircraft out the door at record rates.

In the never-ending desire to make aircraft lighter, manufacturers are making increasing use of carbon-fiber composites rather than traditional metals. In essence, some aircraft, such as the 787 and A350 are largely made of plastic.

And the long, narrow jet engines of the past have been superseded by gaping high-bypass turbofan engines. (The engine nacelles on the 777 are approximately the same diameter as the fuselage of a 737.) And those engines power aircraft on nonstop flights lasting up to 18 hours, a feat that would have required multiple stops for their predecessors.

Written by David Keller

One of the most renown and enduring names in the history of commercial aviation is that of American Airlines. While many other pioneers of the airline industry have fallen by the wayside, American has persevered for over 8 decades, surviving economic collapse, wartime, and terrorist attacks.

The seeds that would eventually sprout and combine to form American Airlines were sown in the 1920’s. Like many of the US trunk carriers, American’s formation resulted from an amalgamation of dozens of small, short-lived entities that were acquired by other companies in an error to stitch together a nationwide air network.

One such airline was Colonial Air Transport, which operated between New York and Boston, as depicted on the June 1, 1929 timetable. Colonial also had divisions known as Colonial Western and Canadian Colonial, which operated to Cleveland and Montreal respectively.

Another of those early lines was Universal Air Lines. The timetable dated November 1, 1929 shows 5 divisions being operated, representing airlines which had been added to the Universal system in the past few years. Universal and Colonial were quickly gobbled up by The Aviation Corporation, which began operating as American Airways in 1930.

The February 10, 1930 American Airways/Universal Division timetable is one of the earliest to display the American Airways name. Other timetables were still being issued for the other divisions, and the only logo appearing on the timetable is that of Universal Air Lines.

By mid-1931, American Airways had started using an early version of the familiar AA logo with the eagle, although timetables were still issued by division. The illustrated timetables from the Universal and Embry-Riddle Divisions show that a standard format was being used across the system. Additionally, each has a promotional message on the back entitled, “A Nationwide Network of Airlines”, to promote the American Airways system as a single entity.

The October 17, 1931 issue dispenses with the individual divisions and, with the exception of Alaskan operations, brings everything together into a single timetable. The route map shows the carrier’s (somewhat circuitous) transcontinental network.

The timetable dated February 1, 1934 was issued shortly before the Federal government decided to cancel all airmail contracts later that month. Air Mail contracts were the lifeblood of the industry and the survival of the airlines operating those contracts was put into serious jeopardy by this action.

After a few disastrous months of having the air mail routes flown by the military, new contracts were awarded, with the caveat that those possessing the cancelled contracts, would not be eligible to bid on the new ones. The existing airlines simply altered their names to become “new” applicants, and ended up receiving contracts that closely resembled those they had lost a few months prior. The June 15, 1934 timetable shows the carrier now operating as “American Airlines”, albeit with the same logo employed under the prior name. This timetable also contains an ad for Curtis Condor sleeper service. New aircraft were on the horizon, and the Condor would only remain in service for a few years.

The most significant of those new types was none other than the Douglas DC-3. A development of the DC-2, American was the first airline to place the Three into service in June of 1936. The timetable dated June 1, 1936 has several pages dedicated to the new aircraft and promotes the new services starting “on or about” June 25th.

By 1941, the varied types used in the mid-30’s were gone, frequencies were increasing and the entire schedule was operated with Douglas equipment, either “Skysleepers” or 21 passenger “Flagship Clubs”. Based on that, it appears that the small fleet of DC-2’s the carrier operated prior to the introduction of the DC-3, had already been phased out.

The timetable dated August 1, 1942 shows the impact of the United States entry into World War II. The timetable dispenses with the red, white and blue covers that had been a staple since the mid-1930’s, and also shows reduced services resulting from many of the carrier’s aircraft being put into wartime roles.

After the end of the war, American and the other US airlines were clamoring for newer, larger equipment. In March of 1946, American Airlines began service with the Douglas DC-4. The timetable dated March 27, 1946 shows DC-4’s operating American’s “Mercury” transcontinental service.

The following year saw the DC-6 enter service with American. The timetable dated April 27, 1947 promotes one-stop transcontinental service “starting soon”, with service already being offered between Chicago and New York. This type proved to be popular with the airline, and was utilized until the mid-1960’s, making it the last piston-powered type to be retired from American’s fleet.

Continuing the rapid succession of new equipment introductions, American became the first operator of the Convair 240 in early 1948. In just over a year, the Convairs had replaced the DC-3 on the shorter segments, and the timetable dated April 24, 1949 shows the schedule operated entirely by the DC-6 and Convairs.

Another facet of American’s operations after the war was its Transatlantic services via American Overseas Airlines, made possible by the acquisition of American Export Airlines in 1945. DC-4s, Constellations and Stratocruisers flew for AOA before American sold the division to Pan Am in 1950. The Transatlantic Service timetable dated May 1, 1948 depicts a Constellation, which was operating “Mercury” services to Europe.

In 1953, American was once again the first to introduce a new type with the introduction of DC-7 service in November, 1953. The November 1, 1953 timetable contains a full page promotion for the aircraft, despite the fact that it wasn’t slated to enter service until November 29th. The DC-7 enabled American to offer the first nonstop transcontinental service in both directions. (TWA began eastbound-only nonstop service a few months earlier.)

January, 1959 saw the simultaneous introductions of American’s first turboprop and pure-jet types. The January 23, 1959 timetable shows the Lockheed Electra operating between New York and Chicago, with service to Detroit following shortly thereafter. The Electra served in American’s fleet for approximately 10 years, before being retired in the interest of an all-jet fleet.

The same timetable also shows the introduction of the Boeing 707 on the New York to Los Angeles run. Flight times were 4 ½ hours eastbound, with the return trip requiring an additional hour. Being the first to operate jet service domestically, the 707 received a full-page promotion, while the Electra didn’t receive any mention at all.

In the summer of 1960, the Boeing 720 entered service with American. This was a shorter, lighter, reduced-range version of the 707 designed for routes not requiring a 707’s capabilities.

For all the advantages the early jets offered by cutting flying times, they were actually somewhat underpowered. A step toward remedying this situation came in the form of the turbofan engine, which had greater thrust and did not require water injection which was utilized by the early turbojets. The timetable dated February 5, 1961 contains a promotion for the introduction of the new fanjet-powered 707, which the carrier dubbed “Astrojet”. Besides taking new deliveries of the fanjet 707s, American decided to convert all of their previously-received aircraft to the “B” standard, with fanjet engines. This timetable also shows the carrier differentiating between the 707s and 720s in its fleet, although this would be short-lived, and all aircraft in the 707/720 family would soon be generically identified as 707s in the timetables.

Joining the Boeings in 1962 was General Dynamics’ Convair 990. Although the 990 was intended to be a fast aircraft capable of transcontinental operations, the promised performance was never achieved, and as the April 29, 1962 timetable illustrates, they were utilized on shorter routes. The 990 only remained in the American fleet for about 6 years.

As the manufacturers shifted their focus to smaller jetliners, American signed up for Boeing’s model 727. The new trijet went into service in April of 1964 between Chicago and New York. The routes that appeared in American’s quick reference specified all of the jet equipment as “Astrojets”, so it isn’t possible to determine which flights were being operated by the 727. However, one of those flights continued to Dallas, and is shown in the columnar section of the timetable where the jet types were specified individually. Although there are no promotions for the 727 in this timetable, the October 5, 1964 timetable does have a full page ad for the 727, which was fulfilling a new schedule of 5 roundtrips between Cleveland and New York.

Continuing the trend towards smaller jets, American also purchased the British Aircraft Corporation One-Eleven to serve on short hauls. The 1-11 was placed into service on March 6, 1966 between New York and Toronto. Although largely used for high-frequency services from New York, the twinjets would eventually operate as far afield as Dallas. In the end, the 1-11 was another short-timer in American’s fleet, and disappeared from the schedule by early 1972.

The Trans-Pacific route case was a political football that had been kicked through 4 presidential administrations, with recommendations being made only to be later overturned. The case finally concluded in 1969, which resulted in American receiving route authority to Hawaii with continuing service to the South Pacific, including Australia and New Zealand.

The timetable dated October 1, 1969 shows displays a pineapple on the cover and has a “Pacific Here We Come” promotion on the back cover. However, service wouldn’t actually start on the new routes until the following August. The August 1, 1970 timetable contains a special supplement highlighting the new service. In the mid-1970’s American swapped these routes to Pan Am, receiving Caribbean routes in exchange.

As much as the race was on to inaugurate jet flights in the late 1950’s, 1970 was a competition to offer 747 service. American’s initial 747s weren’t due until the Summer of 1970, but to avoid losing ground to TWA (which inaugurated service in February), American utilized leased aircraft from Pan Am, and was able to start transcontinental 747 service in early March, only a few weeks after TWA. The March 2, 1970 timetable touts the new service with several promotional mentions.

The following March, American completed the acquisition of Trans Caribbean Airways, gaining routes to 6 Caribbean destinations. The March 2, 1971 shows some of those flights still being operated with DC-8 aircraft formerly operated by Trans Caribbean. (Those would quickly be replaced by American’s own 707s.)

American’s next widebodied type, the DC-10, went in to service in 1971. Despite being the first carrier to place the DC-10 into service on the Los Angeles – Chicago run in August, the July 6, 1971 timetable contains no acknowledgement of the new aircraft. (It does have a very nice color centerfold promotion for the 747, though!) The September 13, 1971 does feature the DC-10 on the cover.

Late 1973 saw the airline industry reacting to the shock of the Arab Oil Embargo, which reduced the availability of jet fuel, eventually resulting in carriers operating with reduced fuel allocations. Airlines quickly grounded many of their gas-guzzlers, which were generally either older first-generation jets or 747s, in favor of smaller types. The October 28, 1973 timetable, which was printed before the Embargo was announced, features a DC-10 on the cover, and 12 daily 747 departures from Chicago. In the January 7, 1974 timetable (which features 727s on the cover), many schedule changes were made, including the removal of many 747’s from active service. In this issue, there were no longer any 747 services being offered to Chicago.

The Airline Deregulation Act was passed in 1978, allowing airlines much more freedom to set fares and enter new markets. The initial flurry of new route applications was for dormant route authority, plus each airline was allowed entry on one route of its choosing. While most airlines proudly announced new routes in their December timetables, American waited until their January 20, 1979 timetable to inaugurate the new services. (However, none of the new cities appear on the route map in this issue.)

In the deregulated environment of the 1980’s, the airlines focused on expansion, both through mergers and the creation of hubs. Much of American’s expansion was achieved by adding international routes to its network. In the summer of 1982, American was awarded its first European route connecting Dallas/Ft. Worth and London, courtesy of Braniff International’s bankruptcy. The June 1, 1982 timetable shows the new service, although it only merited a one-line blurb on the route map page.

Later in 1982, American put the Boeing 767 into service, its first new model in over a decade. The November 1, 1982 timetable dedicates most of the back cover to promote the inaugural service, unfortunately, equipment was not being specified in order to determine which flights the 767 was actually operating.

The following summer, another new aircraft joined the fleet, this time a McDonnell Douglas offering, the MD-80 (dubbed Super 80 by American and other carriers). These planes arrived as part of a small order on very favorable terms, in the hope that the carrier would be pleased and order more. This worked out very well for the manufacturer, as American would eventually amass a fleet of over 300 MD-80s.

Most airlines have “regional” code-sharing partners nowadays, and American’s November 1, 1984 shows the modest beginnings of American Eagle. Seven destinations were served from Dallas/Ft. Worth, operated by Metro Airlines. Today, American Eagle services are provided by around 10 airlines operating hundreds of aircraft, most of which are regional jets.

American was one of the more aggressive airlines in the hub-building arena. In addition to its major hub operations in Chicago and Dallas, the April 15, 1986 timetable shows the creation of a new hub in Nashville. American initially operated 20 routes from Nashville, with 9 additional routes being flown by American Eagle.

By the spring of 1987, American was serving 8 European destinations, but had yet to acquire highly-coveted routes to Asia. In the April 5, 1987 timetable, American was finally able to boast a new Tokyo route, with flights beginning in May. Because American did not have aircraft capable of operating nonstop from its Dallas/Ft. Worth hub to Tokyo, a pair of TWA 747SPs were acquired to handle the service.

The June 15, 1987 timetable saw American engaging in substantial service expansion on both sides of the country. In the east, a new north/south hub had been created at Raleigh/Durham with new service to 35 cities. And in the west, American had acquired AirCal, with those flights being effective on July 1.

The December 17, 1988 timetable shows American building San Jose into a north/south hub on the West Coast. This was part of the “H” route strategy that was thought to be the key to success, having strong north/south route networks in place on the coasts, connected by east/west transcontinental service.

In the summer of 1990, American greatly expanded its international network with the addition of Latin American routes previously operated by Eastern Airlines. The June 15, 1990 timetable details the new service, which would eventually result in an American hub being set up in an almost unthinkable location – Miami!

A little under 20 years after inaugurating DC-10 service, American put the MD-11 into service between San Jose and Tokyo. The MD-11 was essentially a stretched DC-10 (with other improvements), but needed a new model number due to a series of high-profile DC-10 accidents. American (like many of the other MD-11 customers) was not overly pleased with the aircraft, and sold the entire fleet to Fedex.

By the early 1990’s, American was performing hub operations in 7 locations; San Jose, Dallas/Ft. Worth, Chicago, Nashville, Raleigh/Durham, Miami and San Juan. The first of these to falter was San Jose, with American making arrangements for Reno Air to replace it in a number of markets. The timetable dated July 1, 1993 shows a good portion of San Jose services discontinued as of July 15th. Ironically, in 1999, American would purchase Reno Air, thereby reacquiring many routes it had surrendered.

In 2001, American absorbed a much larger carrier, as it merged with the long-ailing TWA. The July 2, 2001 timetable shows the TWA logo with the moniker “An American Airlines Company” beneath it. Unfortunately, events that unfolded later in the year resulted in most of the routes, aircraft and personnel acquired in the merger being shed shortly thereafter.

The darkest day in American’s history came later that year, on September 11th, as two of its aircraft were deliberately crashed, taking the lives of all on board and many on the ground. The first timetable issued after the attacks was the December 15, 2001 edition, displaying the very subdued cover design that would be used on the remaining timetables until the cessation of publication the following summer.

The age of the printed timetable had largely ended, but September 11th didn’t cause the airlines to stop issuing printed timetables, it merely hastened what technology was making inevitable. Several airlines had already stopped printing for prolonged periods (including American, which did not issue a timetable for most of 1999), only to restart publication later.

The past 15 years have been difficult ones for American, as the carrier struggled financially while watching United and Delta grow with their acquisitions of Continental and Northwest, respectively, But American’s recent merger into US Airways (which retained the American name), has vaulted it past it’s competition and made it the world’s largest passenger-carrying airline. The “AA” that graced the airways for some eighty five years will soon be history, but the eagle soars on.

American Airlines,Best Airlines,Braniff International Airlines,Continental Airlines,Delta Air Lines,featured,Frontier Airlines,Horizon Airlines,Midway Airlines,North Central Airlines,Northwest Airlines,Ozark Airlines,Pride Air,Southern Airways,Southwest Airlines,Sunair,timetables,USAir,World Airways

This article appeared in The Captain’s Log, Issue 40-4, Spring 2016

Written by David Keller

Editor’s Note: Some images/figures are spread throughout the article. Images referenced in the article that do not appear within the article body are included in a slideshow gallery at the bottom.

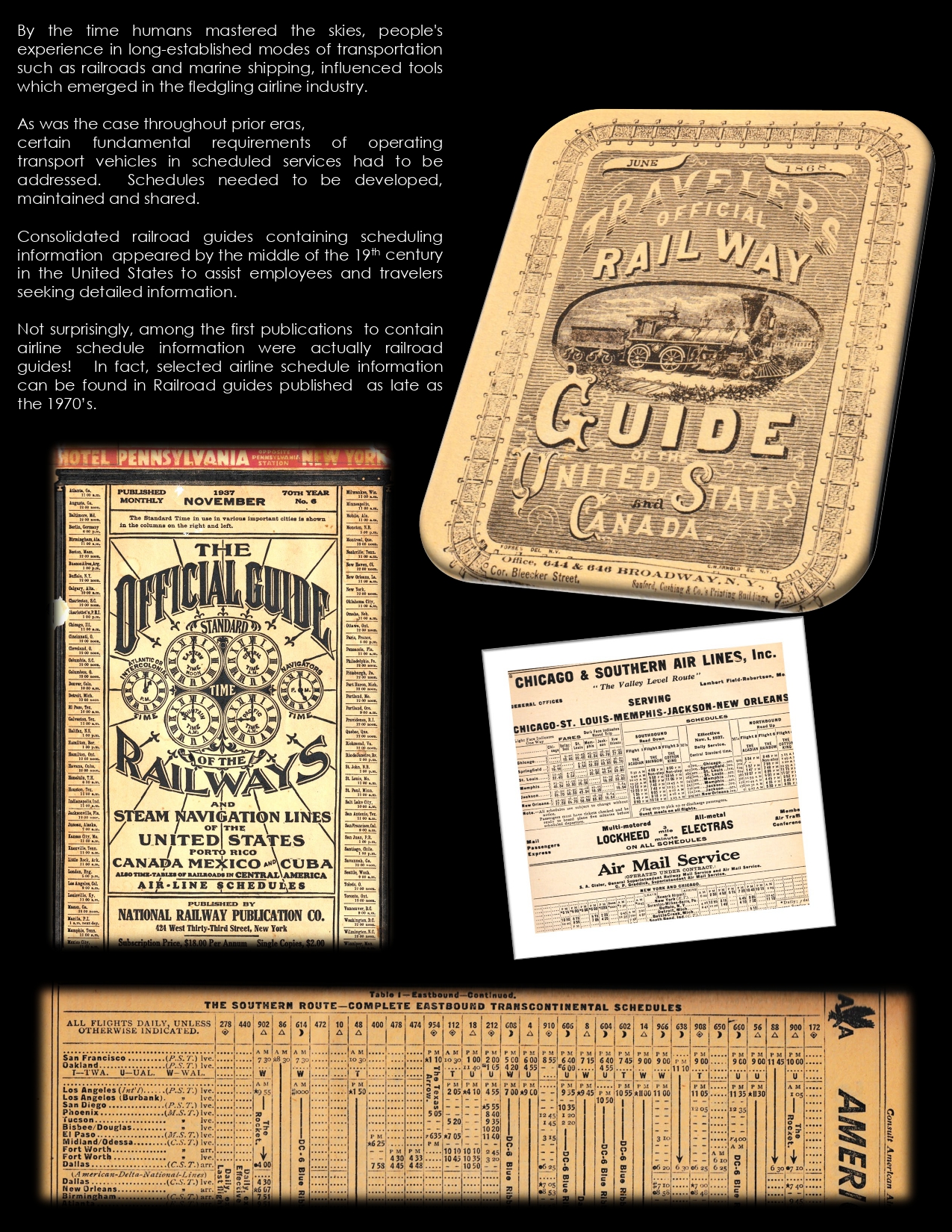

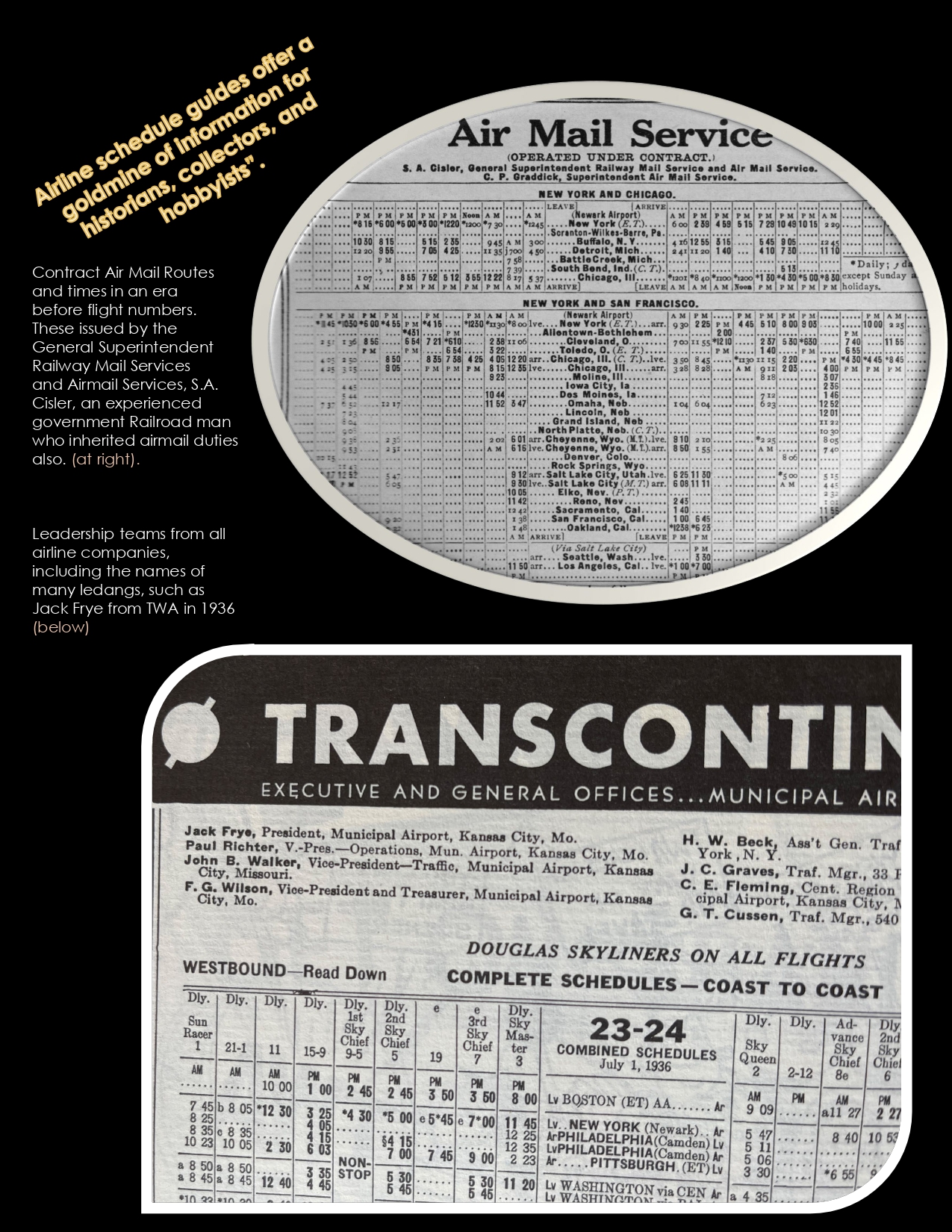

1975. The average American family didn’t have mobile phones, computers or internet service, and TV options consisted of the handful of local stations nearby. Except for a few visionaries, we wouldn’t have been able to imagine the digitally connected world of today.

Most commercial jetliners were manufactured in the US, with DC-9s, 737s and 727s (especially 727s!) just about everywhere. You could walk up to a ticket counter in nearly any airport or ticket office and come away with a printed timetable for your efforts. And the first issue of Captain’s Log was distributed by the World Airline Hobby Club (WAHC).

All fares and route authority in the US had to be approved by the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB). Fares generally fell into a few basic categories (Coach, First Class, etc.) and (with some limited exceptions) did not differ between carriers. It also wasn’t possible to fly nonstop between certain cities, such as between Denver and Atlanta (which even then were two of the nation’s busiest airports).

The 11 trunk and 8 local airlines typically operated with load factors that hovered around 50%. And it was possible to book a multi-stop flight in many markets.

The cover of the illustrated Delta timetable dated October 26, 1975, shows the airline’s special bicentennial logo. [Fig. 1] Later issues (i.e., March 1, 1976) depicted the widget with stars and stripes overlaid on it, which was the design that was applied to the logo near the forward door on Delta’s fleet. [Fig. 2] The itinerary section finds the workhorse DC-9s operating a number of multi-stop flights with as many as 9 segments.

American Airlines’ October 26, 1975 timetable shows another feature that disappeared shortly thereafter; fares for each route. While some routes only display the traditional Coach, Night Coach, First Class, and Deluxe Night Coach fares, others show various Excursion fares, which were an early step that would lead to the proliferation of fares in existence today. [Fig. 3]

For those not in a hurry, Frontier Airlines’ June 1, 1976 timetable offered a leisurely five stop itinerary between Dallas and Memphis, which required just over 4 ½ hours. This timetable also shows Frontier’s pending route applications, including the coveted Denver/Atlanta service. [Fig. 4]

While the trunk carriers operated all-jet fleets, each of the local carriers had a fleet of propeller aircraft to serve smaller communities. While in most cases that meant turboprops, Southern Airways bucked the trend by keeping a fleet of piston-powered Martin 404s in service. The March 1, 1975 timetable shows service from Atlanta, with the Martins identified by 800-series flight numbers. [Fig. 5]

By the mid-1970’s, the local carriers were eager to dispose of their remaining propeller aircraft, and in order to do so, often collaborated with commuter airlines to take over routes that were not suitable for larger pure-jet equipment. (In other cases, commuter airlines jumped in on their own to fill perceived voids in service.)

The result was a large number of commuter airlines being formed in the late 1970’s and early 1980’s. Many failed in short order, the most drastic example being Sunair in Florida which reportedly only operated a single flight. The timetable dated January 15, 1981, shows that service was planned for 15 Florida cities. [Fig. 6]

Other commuter airlines achieved much greater success. Horizon Airlines began service from Seattle to Yakima on September 1, 1981. The airline was able to capitalize on opportunities that arose when competitors abandoned markets (or went out of business), and was later able to establish a relationship with Alaska Airlines which is still in effect to this day. [Fig. 7]

In late 1978, the US airline industry was turned on its head with the passage of the Airline Deregulation Act. This allowed airlines far more freedom to set their own fares and enter new markets. Initially, carriers were allowed to apply for “dormant” route authority, (i.e., authority being held by other airlines but not being operated). In addition they were allowed free entry into a single market of their choosing.

Recipients of new route authority had a relatively short time frame in which to start service, or risk losing that authority. This meant that many new routes were opened in late 1978 and early 1979, and were often promoted on the timetables.

Ozark and North Central both issued timetables dated December 15, 1978, which trumpeted new service to highly sought after markets, most notably, Florida. On this date, Ozark began serving 4 Florida cities, while North Central added 5. [Fig. 8] [Fig. 9]

Some airlines were cautious, only adding a small number of routes and new destinations. Continental’s timetable dated January 15, 1979 shows Washington D.C. as the only destination added by the carrier. [Fig. 10] National Airlines added San Juan and Seattle, with both being promoted in the March 2, 1979 timetable. [Fig. 11]

On the other hand, there was Braniff International Airways which threw caution to the wind. They camped out at the CAB to be first in line when applications were being accepted for dormant routes. Their December 15, 1978 timetable shows 30 new routes being operated, and 15 cities added to the network. It was a go-for-broke strategy, and succeeded in bankrupting the airline less than 3 ½ years later. [Fig. 12]

Another facet of Deregulation was the certification of new carriers for scheduled service. The first to take advantage of this were the supplemental airlines, which already had fleets and staff available. World, Capitol and Trans International were all operating scheduled services by the summer of 1979.

World Airways wasted no time transitioning to scheduled service. The timetable dated April 12, 1979 shows daily flights shows 2 roundtrips being operated between Newark and Los Angeles, with continuing service to Baltimore and Oakland. [Fig. 13]

The first brand-new startup was Midway Airlines. The timetable dated October 31, 1979 shows new service from Chicago’s then under-utilized Midway Airport to Cleveland, Detroit and Kansas City. Prior to that point, service to Midway Airport consisted of a handful of lightly-loaded flights. Within a few years, Midway Airlines had built the airport into a busy hub, attracting millions of passengers and numerous airlines. [Fig. 14]

The floodgates were opened, and many new airlines were proposed in the next few years. Some never made it off paper, and others never got into the air. And of those that did, most only lasted a few years, some, only months.

So many new airlines were being created, that the traditional 2 letter airline codes were being used up. At first, duplicate codes were assigned to scheduled airlines which had previously been assigned to airlines not offering scheduled services. Then, in 1981, airline codes began to appear which had numeric digits to increase the number of possible codes and alleviate the problem.

Best Airlines began service in 1982, and the timetable dated September 13, 1982 shows 2 aircraft operating to 10 destinations. Best may have been the most mobile airline ever, as it seemed that they dropped destinations and added new ones with almost every new timetable. Operations ceased in late 1985. [Fig. 15]

New Orleans-based Pride Air enjoyed a much shorter run. The inaugural timetable dated August 1, 1985 features service to 15 destinations, as the carrier attempted to establish a hub on the Gulf Coast. Only one additional timetable was issued (on October 1) before operations were halted in mid-November. [Fig. 16]

By the mid-1980’s, the tide turned, and the number of airlines operating in the US began dropping. One reason was that most of the new entrants failed rather quickly, as previously mentioned. Another was that the mainline carriers were establishing code-sharing arrangements with the commuter airlines, to provide a common brand, such as American Eagle or Northwest Airlink. The advantage to the qualifying airlines cannot be overstated, and those without such agreements found it difficult to complete. Some merged, and most eventually ceased operations, either voluntarily or otherwise.

In the second half of the 1980’s a number of major carriers were absorbed through mergers, Air Cal, Ozark, Piedmont, PSA, Republic and Western among them. From a timetable standpoint, some of those carriers disappeared without any mention by the surviving airline.

USAir’s timetable dated April 9, 1988 promotes its acquisition of PSA. Perhaps not the best combination from both equipment and route structure viewpoints, most of PSA’s routes would be dropped within a few years as Southwest expanded its presence on the West Coast, and USAir dealt with the acquisition of Piedmont. [Fig. 17]

A somewhat scarce timetable (given its recent vintage) is Northwest Airlines’ issue dated October 1, 1986. [Fig. 18] This is the only “full” system timetable (showing both direct and connecting flights) that was issued after the merger with Republic Airlines. (There were a few international timetables which did show connections but not all services were included.) Northwest changed to a “Frequent Flyer” format, which contained only direct flights, a format which was eventually adopted by nearly all major airlines in the US.

The early 1990’s saw the United States and numerous other coalition members go to war with Iraq. Most airlines struggled with the resulting travel downturn, some went to bankruptcy court, and others failed outright. Midway Airlines became one those casualties in 1991, halting operations after almost 12 years, and having outlasted dozens of airlines that started service in that period.

By the middle of the decade, business conditions were improving, and the allure of the industry was too tempting for some, resulting in a new round of airline creation. Some created “hub” operations in unlikely places such as Colorado Springs, Reno, and Savannah. Others offered service from under-utilized airports serving large cities, to avoid the congestion and higher costs involved with operating to the more popular stations.

Western Pacific inaugurated service in 1995, with the intention of using Colorado Springs as an alternative to the recently opened Denver International Airport, which was 19 miles further from downtown Denver than Stapleton. Particularly for customers in Denver’s southern suburbs, the trip to Colorado Springs was judged to be not much greater than that to the new airport.

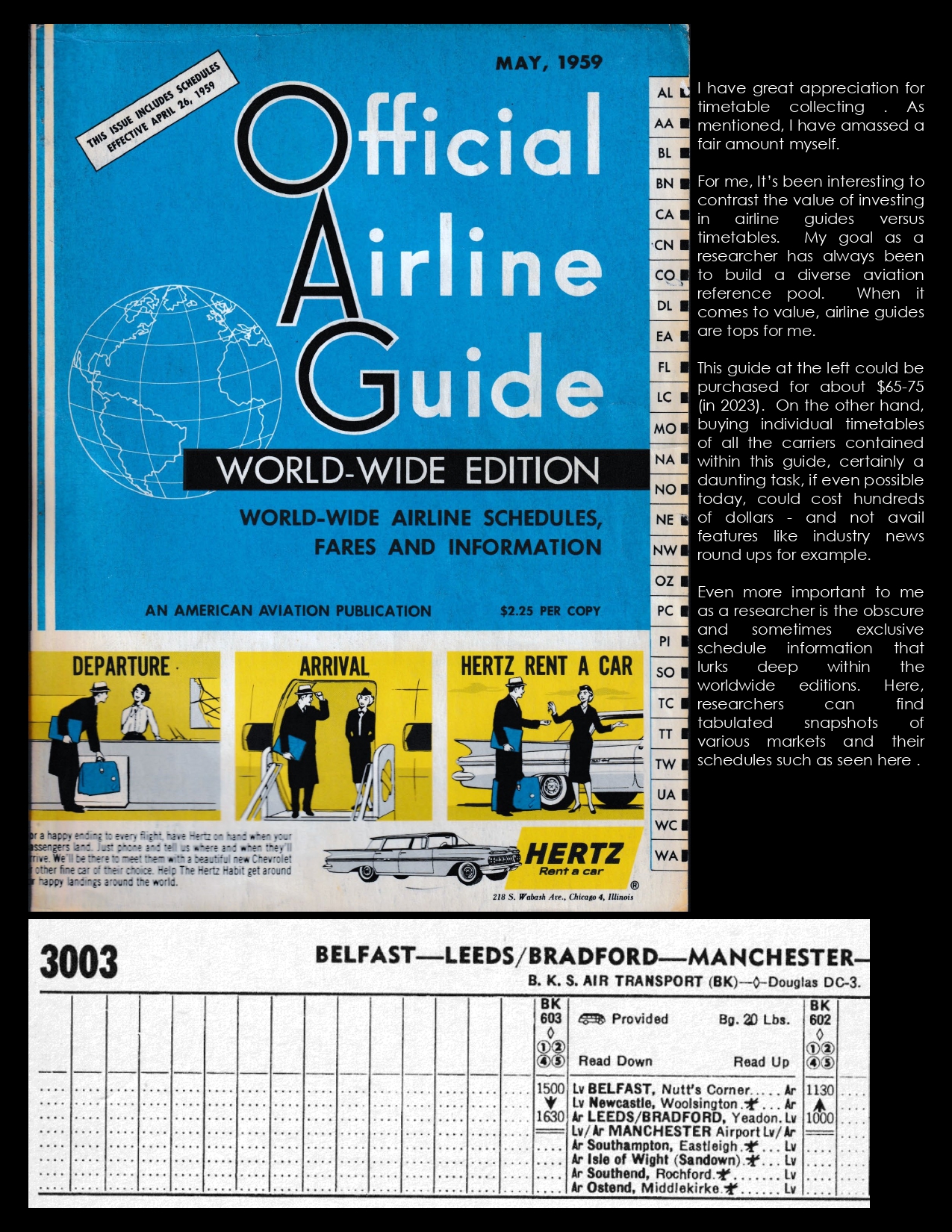

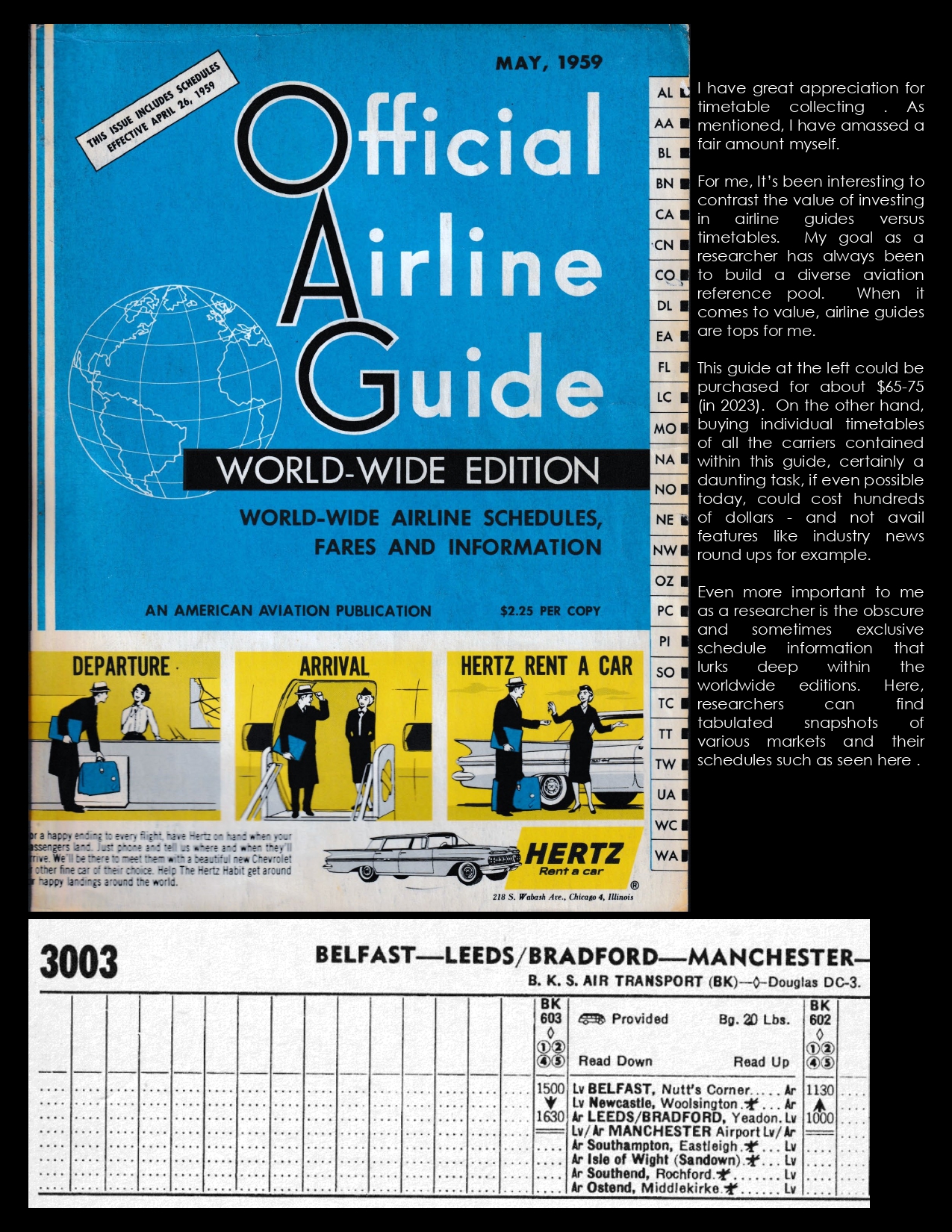

The carrier’s timetable dated October 29, 1995 shows several of the airline’s Logojets, which were essentially flying billboards that the company used as an additional source of revenue. The Colorado Springs hub did not work out, and by 1997, the carrier was exploring a merger with Frontier Airlines and moving its operations to Denver. The merger plans did not materialize, and Western Pacific shut down shortly thereafter. [Fig. 19]