Henry Ford’s Tin Goose Lays a Golden Egg

Written by Henry M. Holden

Today, when we fly commercially we think of aircraft in terms of a name and number, for example, Boeing 747, or Airbus A380. Nowhere in an airport or on the airplanes will we see the name, Ford.

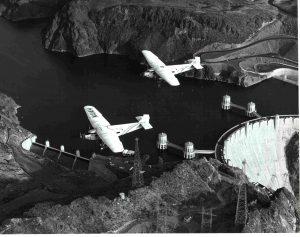

Scenic Airlines operated two Ford Tri-Motors flying tourists over the Hoover Dam and the Grand Canyon for more than 65 years. (Henry M. Holden)

Over 90 years ago a man had a vision. He foresaw the day when people would be transported on a commercial airline network spanning the United States, and the world in a safe, comfortable, and reliable way. His name was Henry Ford.

Ford took the airplane, considered by most people at the time to be a noisy and dangerous machine, and transformed it into a successful commercial product. His product was radically different. His all-metal airplane design called the Ford Tri-Motor, affectionately called the “Tin Goose,” would lay a golden egg. The Ford Tri-Motor was the seed that spawned commercial aviation in the United States.

The early production line for the Ford Tri-Motor was duplicated from Ford’s assemble line. (author’s collection)

The story of the Ford Tri-Motor begins with William Bushnell Stout, who during World War I, worked for the Packard Motor Car Company, as the chief engineer of their aircraft division.

As the war ended, Stout designed an airplane for army called the “Batwing.” It was the first American-built internally-braced cantilever-wing monoplane. It also had the first plywood veneer used as an airplane skin in the United States. By the time it flew, the war had ended, and the army had lost interest.

With so basic an instrument panel the oil temperature and pressure gauges were mounted on the engine strut and easily seen from the cockpit. (Henry M. Holden)

The Batwing drew the attention of the navy who commissioned Stout to build an all-metal twin-engine torpedo bomber. It crashed during a test flight, and never went into production.

Unique financing

After this failure, Stout turned to the commercial market for financing of a new design. He sent letters to 100 Detroit industrialists, including Henry Ford, asking for $1,000 from each. He received about 65 responses. Stout raised $20,000, including $1,000 each from Edsel and Henry Ford.

Stout’s AS-1 The Air Sedan first flew on February 17, 1923, and its performance was poor. Stout wanted to build a larger airplane with a more powerful engine. (author’s collection)

Now with enough funds, Stout incorporated the Stout Metal Airplane Company on November 6, 1922, “to develop and manufacture aircraft.” Stout’s first design was a four-passenger monoplane made of metal and powered by an OX-5 engine. He called it the Air Sedan (AS-1). The Air Sedan first flew on February 17, 1923, and its performance was poor. On the test flight it was obvious the plane lacked power. Stout “found” a Hispano Suizza engine, and with this new engine, the plane flew satisfactorily. When Ford heard of Stout’s experiments he began to consider the possibilities for commercial aviation.

In a conversation Stout had with Henry Ford, Stout told Ford that he wanted to build something more powerful than the Air Sedan, one that could carry 10 people (two crew and eight passengers) or the equivalent in cargo, have a high wing and use of 420 hp. Liberty engine.

2-AT

Stout’s next design was the 2-AT “Air Pullman,” which first flew on April 23, 1924. It was a single engine high wing monoplane built entirely of corrugated duralumin. Stout’s idea to build an airplane completely out of metal was radical. The U.S. Airplanes were being built of fabric stretched over wood or metal frames.

Stout had named his airplane “Maiden Detroit” to promote civic interest in his venture. When it was used for freight it was called the “Air Truck” and was the first Stout plane to have the Ford emblem on its fuselage.

One of Stout’s 2-ATs at work carrying mail for Florida Airways. Note the open cockpit and thick wing root. (author’s collection)

In December 1924, the U.S. Post Office bought “Maiden Detroit” to carry airmail. This gave Stout’s company the financial boost it needed. By March 1925, his “Maiden Dearborn,” was ready for tests.

On April 13, 1925, “Maiden Dearborn” left Detroit for Chicago. It was the first flight of the Ford Air Transport Service, inaugurated by Ford to carry auto parts, company mail, and executives to his Chicago plant. Soon 2-AT “Maiden Dearborn II” was placed in service on this line. On July 31, 1925, Ford bought Stout’s company, and it became the Stout Metal Airplane Division of the Ford Motor Co. By December 1925, Stout had manufactured 11 single-engine 2-ATs, and five were used by the Ford Air Transport Service.

On August 25, 1925, Ford announced his entry into the commercial aviation field. “The Ford Motor Company,” he said, “means to prove whether commercial flying can be done safely and profitably.”

Ford Air Reliability Tours

Ford tried to convince the public that flying in a Ford plane was the right thing to do. In August 1925, he established the Ford Air Reliability Tours, covering thirteen cities and 1,900 miles. The event was open to all aircraft manufacturers and it attracted Europe’s best-known aviation figure, Dutch-born, Anthony Fokker. For the race, Fokker converted his newest transport, a single engine F.VII, to a tri-motor.

There is speculation that a glimpse at the plans for Ford’s Tri-Motor prompted him to do this. The modified Fokker dominated the race coming in first, followed three minutes later by the Ford entry, a single engine “Air Sedan.” Both Ford and Fokker profited enormously from the publicity. The publicity Fokker received was enough to launch his airplanes on a successful career in America.

Birth of the Tri-Motor

Not completely satisfied with the 2-AT, Ford directed Stout to build a larger airplane with three engines. Stout took the basic layout of the 2-AT and mounted a Wright Whirlwind air-cooled radial engine under each wing, and a third in the nose. The nose was rounded with windows to give forward vision for the passengers. The pilot’s open cockpit was placed above the cabin, and wing which gave the pilot poor landing visibility.

The 3-AT presented a hideous appearance and was labeled a “monstrosity,” by observers. The test pilot, R. W. “Shorty” Schroeder, almost crashed it on landing. His report to Ford and that of another test pilot convinced Ford he had a “lemon.” Ford was angry, and his friendship with Stout dissolved.

The 3-AT presented a hideous appearance and was labeled a “monstrosity,” by observers. Ford believed he had a “Lemon” on his hands and was angry. His friendship with Stout soon dissolved. (author’s collection)

A mysterious factory fire the night of January 17, 1926, destroyed the 3-AT and Stout’s earlier designs. Stout was sent on a speaking tour to promote aviation, and a new group was formed to design a new tri-motor.

The plate that appears on every Tri-Motor implies that Stout designed the airplane. (Henry M. Holden)

For years, Stout was credited with having designed the Ford Tri-Motor, although he never made that claim himself. The original 4-AT design was the result of the ideas of several men, and none claimed exclusive credit for it. Tom Towle, an assistant to Stout figured prominently in the design. Towle was directed to lay out the design and others were brought in to assist him. Towle took the general layout of the 2-AT as the basis for the 4-AT design.

The 4-AT was a vast improvement over the 3-AT. On June 11, 1926, it made its first flight. The test pilot reported that the plane’s performance was perfect.

This Ford, 4-AT-10, C-1077 was the tenth off the assembly line and is the oldest flying Ford. (Henry M. Holden)

Although designed primarily for passenger use, the Tri-Motor could be adapted for hauling cargo, since its seats could be removed.

The Ford Tri-motor resembled the Fokker F.VII tri-motor, but unlike the Fokker, the Ford was all-metal, allowing Ford to claim it was “the safest airliner around.” Its fuselage and wings followed a design pioneered by Hugo Junkers during World War I and used post war in a series of airliners some of which were exported to the U.S.

Constructed of aluminum alloy, which was corrugated for added stiffness, the corrugations resulted in drag, and reduced its overall performance. So similar were the designs that Junkers sued, and won when Ford tried to export an aircraft to Europe. In 1930, Ford counter sued and lost a second time, with the court finding that Ford had infringed upon Junkers’ patents.

Unsafe in any tri-motor

Although the Ford and Fokker airplanes dominated the commercial aviation network of the late 1920s, they had serious deficiencies, and lacked the basic creature comforts. The airplane would still have to demonstrate that it was relatively safe, reliable and comfortable. This would not be easy for the Fords and Fokkers.

The Eastern Air Transport passengers are dressed for what appears to be a cold winter clothing. Note an EAT employee in shirt sleeves. (author’s collection)

There were accidents where the wings separated from the wooden planes in flight. If a Ford had an engine failure on take-off, the resulting vibrations, and the poor airflow over the corrugated skin, would sometimes cause the plane to stall. Engineers had their work cut out for them if they were to solve the technical problems that plagued the early aircraft.

The popularity of Ford’s plane stemmed from its appearance. It had no wires or struts, and its metal skin had corrugations running span-wise. Aluminum was stronger than wood, and Ford tried to convince the public his planes were safe and comfortable. An advertisement for the Ford Tri-Motor said, “Your comfort is given the same consideration as has been given structural strength. The fuselage is enclosed and plenty of windows allow good visibility and ventilation. Exhaust manifolds throw the sound away from the fuselage and padding of the compartment further muffles it. Conversation is carried on with ease. Large upholstered chairs assure riding ease for twelve passengers.”

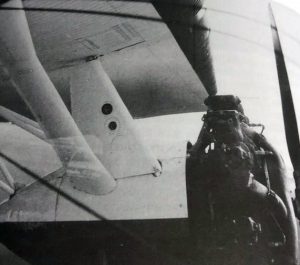

The Bell Telephone Laboratories Ford Tri-Motor is bristling with antennae. The laboratories made significant inroads to improving air to ground communications. (author’s collection)

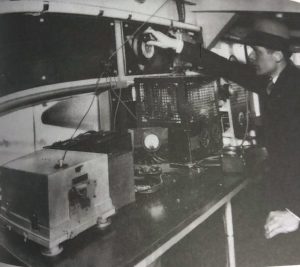

The interior of the Bell Telephone Laboratories Tri-Motor, seen here flying over the ocean. Making an antenna test at the test bench is F.S. Bernhard. (author’s collection)

This was at best a benign overstatement and in no way resembled reality. While the advertisement spoke of comfort and safety, the cabin was not heated and the sound level inside a Ford was 117 decibels, which could permanently damage a person’s hearing.

Copilots handed out packs of chewing gum, cotton, and ampoules of ammonia. The gum was to equalize the pressure on the passenger’s ears, the cotton blocked out some of the noise, and the ammonia was to relieve air sickness. Air sickness was so common on the southwestern flights of Transcontinental Air Transport that someone suggested putting pictures of the Grand Canyon on the bottom of the air sick cups, so no one would miss the view.

When passengers arrived at their destination, they got off the Tri-Motor physically and psychologically exhausted. Their bones ached, their nervous systems were a jumble of skinny wires all sounding different notes, and their heads pounded from the constant propeller noise.

One of the last surviving Ford Tr-Motors, NC8407 is still earning revenue (as of 2018) at the Experimental Aircraft Association’s annual AirVenture in Oshkosh, WI. (Henry M. Holden)

One hundred ninety-nine 4-AT and 5-AT Ford Tri-Motors were built. The army, navy and Marines each used the Ford. The deepening economic depression, and the appearance of new and faster types forced the Ford Tri-Motor out to grass. The Ford would prompt William Boeing to come up with something better, the Boeing 247.

We see the author here in 1982 at Herndon Airport in Orlando. This Ford N7584 4-AT was destroyed in hurricane Andrew in1992. (Henry M. Holden)

Henry M. Holden is the author of “The Fabulous Ford Tri-Motors” available on Kindle

Trackback from your site.

Clive Arnold-Green

| #

Do any passenger lists still exist for this airline? I am hoping to find information from 1960.

Regards,

Clive Arnold-Green

Reply

Scott Elliot Jones

| #

Has the privilege of flying twice this year on the EAA trimotor out of Orange County. What a thrill. I didn’t think it was as noisy as purported to be.

Reply