Looking Back

By Henry M. Holden

The 20-year period between the end of World War I and the beginning of World War II has been called the “Golden Age of Aviation.” During this time, airplanes morphed from slow, wood and fabric-covered biplanes to fast, stream-lined, all-metal monoplanes.

Civilian aviation grew, and many dramatic aerial feats took place. Barnstormers and wing walkers captivated the public with daring feats that often cost many their lives.

There were great expectations that dirigibles would encourage transatlantic passenger service. The Empire State Building, completed in 1931, had a dirigible mast for the ships to dock. And dirigibles did encourage passenger service until the Hindenburg disaster in 1937 killed 36 passengers, and the dirigible business.

The Hindenburg over Manhattan, New York on May 6, 1937, before its demise later that day. (Author’s collection)

It was during this period of aviation growth, that the “plane that changed the world,” the Douglas DC-3 appeared on the scene.

Prior to the DC-3, cross-country travelers would fly in a Ford Tri-Motor during daylight hours, then switch to trains for overnight transport. (Photo Henry M. Holden)

In 1934, the year before the introduction of the DC-3, a flight from New York City to Los Angeles was a grueling ordeal, typically requiring at least 25 hours, at least two changes of airplanes, and as many as 15 stops. Now, a single plane, the DC-3, could cross the country, usually stopping only three times to refuel and pick up passengers and mail.

The year was 1939. It was a cold January afternoon at New Jersey’s Newark Airport. A gleaming polished aluminum American Airlines DST (Douglas Sleeper Transport) sat ready for departure, bound for Los Angeles’ Glendale Airport, in California.

Newark was the only major airline terminal for the entire New York metropolitan area. Ground had been broken for another airport at North Beach, in Queens, New York, and it was due to open in October as LaGuardia Airport.

The 1939 World’s Fair would soon open, in Flushing, Queens, and we were expecting a major influx of tourist to the metropolitan area. LaGuardia would make it convenient for tourist to see the Fair, landing them about three miles from the center of the Fair.

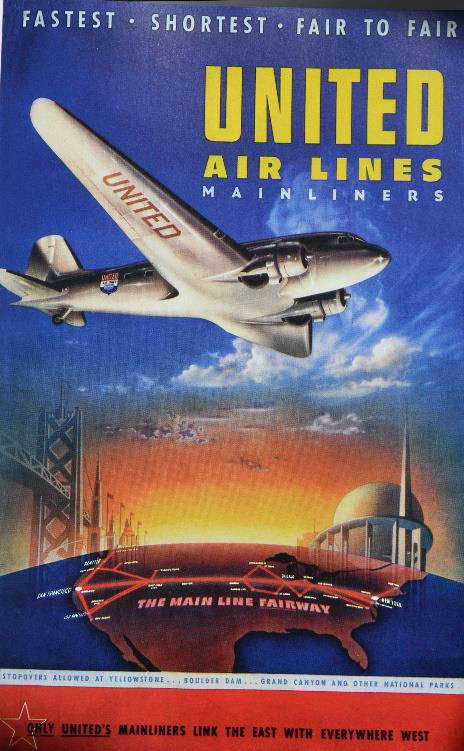

A United Air Lines promotional brochure (TOP) displaying the Golden Gate bridge in San Francisco and the Trylon and Perisphere the symbols of the 1939 World’s Fair in Flushing, Queens, N.Y. American Airlines advertising a trip to San Francisco on a DC-3 ((author’s collection)

The sky was cold and clear, but there were war clouds on the horizon. Hitler had reoccupied the Rhineland in defiance of the Locarno Pact, and there had been open intimidation between England and Germany. We knew it would not be long before we were involved in another war.

For Americans, life was getting better. We felt a gradual easing of the Depression, as more of us were working, albeit in defense related industries.

Rib roasts were selling for 31 cents a pound, and The New York Times was still two cents if I remember correctly.

The rich and famous, and business men could avoid an exhausting one-week coast-to-coast rail trip by booking passage on one of American Airlines’ new DSTs, the first model in the rapidly-becoming-famous DC-3 series.

The DC-3 was introduced into American Airlines service about six months after the Douglas company rolled it out on December 17, 1935. It was the first airplane that could make money flying people and not depend on the mail subsidy.

The DST/DC-3 was an instant success, pushing the noisy and dangerous Ford Tri-Motors quickly to the sidelines

I was on board American Airlines “Mercury Service” Flight 401, Flagship Texas. This flight is part of American Airlines “Flagship Fleet,” named because each new DC-3 proudly carried the name of one of the 48 states in the union. Upon landing, the copilot would “strike the colors,” as the aircraft taxied into the terminal. The flag, bearing the eagle insignia of American Airlines would always snap sharply in the wind above the copilot’s window.

We departed Newark at 5:10 pm and were scheduled to touch down at 8:50 am the next morning in Los Angeles’ Glendale Airport (baring disagreement from Mother Nature)

The same trip by rail took several days, so if you were in a hurry to conduct business, the plane made more sense. Coming east, however seem much longer when we had to push our watches ahead three hours.

The DC-3 was fast for its day. Its cruise speed was 207mph (333km/h) It had super-charged 1,200-horsepower twin engines, cantilevered metal wings, retractable landing gear and steam heat.

The flight was fully booked with 14 passengers, me being one of them.

This was American Airlines Flagship Texas. It was the first DST off the assembly line. NC14988, c/n1494 had two Wright Cyclone SGR-1820 engines. It was sold to the War Department on July 21, 1942. Its Civil Aeronautics Administration registration was cancelled, and it was given USAAF serial number 42-43619. It crashed at Knobnoster, MO October 15, 1942. (author’s collection)

The DST was the height of luxury. Fourteen plush seats in four main compartments could be folded in pairs to form seven berths, while seven more folded down from the cabin ceiling. The plane could accommodate fourteen overnight passengers or up to twenty-one for shorter daytime flights. By rearranging the seating the airlines were later able to increase the capacity to 28 people.

The passenger door was at the rear of the airplane and once aboard each of us had to walk up the aisle. Since the airplane had a tail wheel, we had to walk up an incline of about 30-degrees.

I watched from my seat as the captain did his inspection of the tires and movable wing surfaces. Later, when I asked him, he said he was inspecting tires for wear, and the flaps and ailerons for smoothness of motion.

When the captain came back on board, the stewardess as they were called in those days, closed the door and checked to make sure everyone was buckled up. In those days as part of their job, they were required to be registered nurses.

Suddenly, the propeller on the right side of the airplane started to turn a few revolutions before it went through belching thick white smoke and was spinning at such a rate that one could not count the blades.

A minute later the propeller on my side started that slow lethargic few turns before it belched thick white smoke and was whirling at a dizzying rate.

Then we began a slow, bumpy ride down the taxiway, turned and came to a stop.

The stewardess made a quick walk up the aisle checking that all were still buckled in. She took her seat and spoke something into the telephone hand set she was holding.

Suddenly the roar of the engines became very pronounced. The plane began to vibrate and the noise level increased. One could feel the inherent power of the engines. It was like a race horse straining at the gate to be freed to run the race. About thirty- seconds later the plane suddenly lurched and began to roll forward, picking up speed.

About halfway down the runway, the back of the airplane lifted and was level. The airplane left the ground so smoothly that none of us in the cabin realized what had happened until we saw the lights from the field rushing away behind us and the city lights below winking through the darkness ahead of us.

One hour after takeoff, the DST was drumming south westward in a valiant but futile attempt to catch the setting sun. Ten thousand feet below us the land was wrapped in the covers of darkness with only the electric fires of civilization rolling beneath us sustaining the reality of motion.

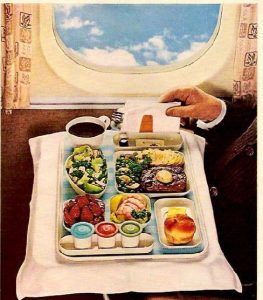

Once airborne, we were served cocktails, but then it was complements of the captain, who said so over the public address system. That was followed by dinner choices of sirloin steak, Long Island duckling, or lamb chops, served on Syracuse China with Reed & Barton silverware and real linen napkins. It was like eating in a high-class restaurant.

During the meal service the captain would send back his written flying report to be passed among his guests, as he called us. Most of us did not understand the technical details of the report but we sure appreciated being informed of our progress and what was ahead of us. In those days flying was still mysterious and for some scary.

We had polished off dinner by the time we over-flew Norfolk, Virginia, and were enjoying desert of ice cream and coffee, and the Sun had yielded to an evening sky of deep purple.

The captain announced that we would be stopping to refuel and pick up the mail in Nashville, Tennessee. When we landed the captain made the landing, in the new style rather than the three-pointer which may frighten some of his passengers. Another crew would take the Flagship Texas, and its sleeping cargo on to Dallas, the next stop.

The DC-3’s primary—and romantic—accomplishment, is that it captured America’s imagination. The journey became the destination. And with good reason: Passengers aboard the plane entered a protected world unbelievable to today’s stressed air traveler. The DC-3 married reliability with performance and comfort as no other airplane before, revolutionizing air travel and finally making airlines profitable.

Transcontinental sleeper flights featured curtained berths with goose-down comforters and feather mattresses. There were also separate albeit small restrooms for men and women

It was a fifteen-hour and 40-minute flight, but when you subtracted the three hours’ time difference it wasn’t a bad trip in those days. Many of us thought that this air liner would revolutionize airplane travel and go down in aviation history as one of the finest air liners ever built.

For the two movie stars on this flight who had paid an additional $160 over the standard round-trip fare of $264, (equivalent to about $3,800 today) they had the privilege of occupying a private compartment known as the “Sky room,” or “Honeymoon Hut,” where they are regularly comforted by the enthusiastic attentions of the stewardess.

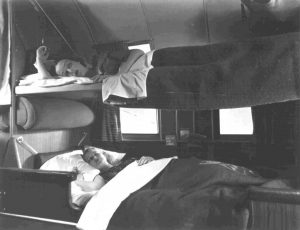

Luxury came to air travel with the DST. The DST had seven upper and seven lower sleeping berths, with a full down mattress. The upper berths folded into the ceiling when not in use. This photo shows one upper and lower berth. Note the double window below and the single slot window above to prevent claustrophobia. (United Airlines)

The captain came out of his office as he called it and walked the comfortably wide aisle of the passenger cabin, pleased to answer any questions his guests might have. I like the idea of being called a guest.

I asked him how he can find his way in the dark. He explained that there were several ways to keep from getting lost. One was the radio direction finder, a radio beacon system that sent out pre-recorded Morse Code signal that told him where he was on course.

Then there were the beacon towers left over from the airmail days that pulsed a light. In the daylight some of the towns and cities had painted the name of the city on the roofs of some buildings, also a left-over from the airmail days.

This is another United Airlines photo showing presumably a married couple in the sleeper berths. (United Airlines)

Later we would all retire to very comfortable berths, designed to the standards of the Pullman sleepers on the railroads. The captain would later walk the same now darkened aisle making sure everything was buttoned down properly.

By then we were all asleep, wrapped in warm cocoons of goose-down comforters nestled snugly on feather mattresses, behind individually curtained upper and lower sleeper berths. This night it was clear, and the two pilots had easily followed the long winking airway lights westward.

This United Airlines photo shows the stewardess (now flight attendant) serving breakfast in bed to the occupant of the upper berth. She is the same person in the previous photograph but in the lower berth. (United Airlines)

We bumped along a bit after departing Dallas, in the wake of a passing thunder storm, but most passengers weren’t bothered by the mild turbulence.

On this Eastern Airlines DST the upper sleeper berth windows are obvious. This is NC25650, c/n 2225, Ship 351 of the Eastern fleet. Delivered to EAL in February 1940 and was impressed into military service as a C-49F 42-56616 for the USAAF in May 1942. It was returned to Eastern in July 1944. (author’s collection)

Oh, I have been on flights where everyone was so sick, we thought we’d die, but this was not one of them. Once airborne out of Phoenix, the stewardess would waken those still asleep and for each of us, serve a hot breakfast. This trip it was fresh coffee, juice and a choice of wild rice pancakes with blueberry syrup or a Julienne of Ham Omelet. She would then tidy up the cabin for our on-time arrival in Glendale Airport.

When we deplaned, we would be refreshed after a long night’s sleep and ready for a new day, more than can be said for today’s jet-lagged and cranky passengers who endure a flight over the same geography.

Trackback from your site.