Airports for the Supersonic Age – Part 1: Planning for SSTs

Written by Marnix (Max) Groot

Published: October 6th, 2019 | Updated: January 31st, 2020

Original article published in airporthistory.org

Dawn of the supersonic age

In the late 1960s, the expectation was that, by the late 20th century, the majority of long-haul passengers would fly in supersonic aircraft.

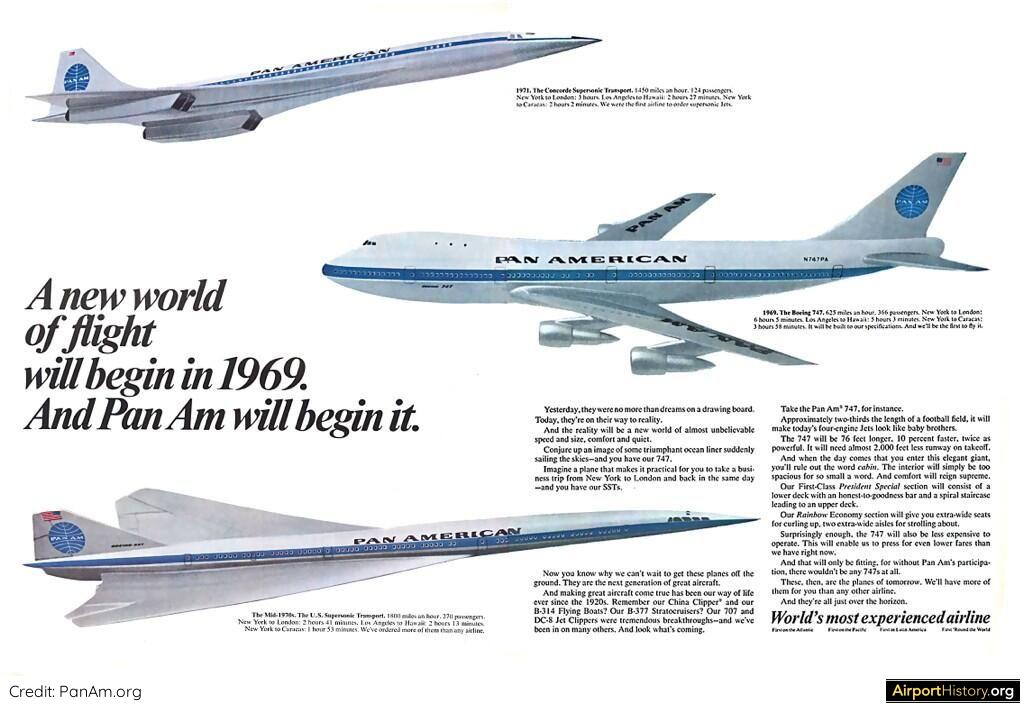

At the time, all major aircraft manufacturers in Europe, the US and the USSR were developing concepts for ‘supersonic transport aircraft’, or SST. The largest SST model, the Boeing 2707 would carry 300 passengers, which was 60 passengers less than the first 747 in a three-class layout. The Anglo-French Concorde carried between 92 and 128 passengers.

In anticipation of this development, Boeing designed the 747 with the characteristic hump, so that it could be easily converted into cargo aircraft if its design became obsolete for passenger transport.

A 1967 Boeing image showing a contemporary 1960s airport concourse, surrounded by existing Boeing models at the time: the 707, 727 and 737 as well as its upcoming Boeing 747 and the supersonic Boeing 2707. With a length of 306 feet (93 meters), the Boeing 2707 was quite a bit longer than the 747 at 231 feet (71 meters).

Despite their spectacular design and performance characteristics, SSTs were designed to make use of existing runways and terminals. However, SSTs did still have an impact the design of airports, or to be more specific, their location. SSTs were extremely noisy. Hence, new airports that were expected to handle SSTs were often planned far away from the cities they served.

In this article, we will examine how some prominent airports in the late 1960s prepared for the supposedly inevitable takeover of the SST!

East Coast

NEW YORK

Being a world city and the primary US international gateway, New York was destined to become the SST capital of the world, with both US and foreign flag carriers operating supersonic service to cities and around the globe.

New York’s Kennedy Airport was the main base for Pan Am and TWA, America’s most prominent international airlines at the time. Both airlines had options on Boeing’s SST as well as the Anglo-French Concorde. In the late 1960s, both airlines commenced expansion projects of their terminals, that were prepared to accommodate the new generation of wide-body aircraft and SSTs.

Read our full history on New York’s Kennedy Airport. Read more about the early days of the Pan Am terminal and TWA Flight Center.

Pan American Airlines, America’s de facto flag carrier, always was on the cutting edge of aviation. The airline had 15 options on the American built Boeing 2707 and 8 options on the Concorde.

A 1968 image showing a model of the upcoming expansion of the Pan Am terminal, which would be renamed the Pan Am Worldport. A Pan Am Concorde is parked at the gate, while a Boeing 2707 is taxiing by.

An advertisement announcing the expansion of the TWA Flight Center. Specific mention is made of SSTs.

A beautiful artist’s illustration of a Concorde in TWA livery. The airline had an option for six aircraft. TWA also optioned 12 Boeing 2707s.

MIAMI

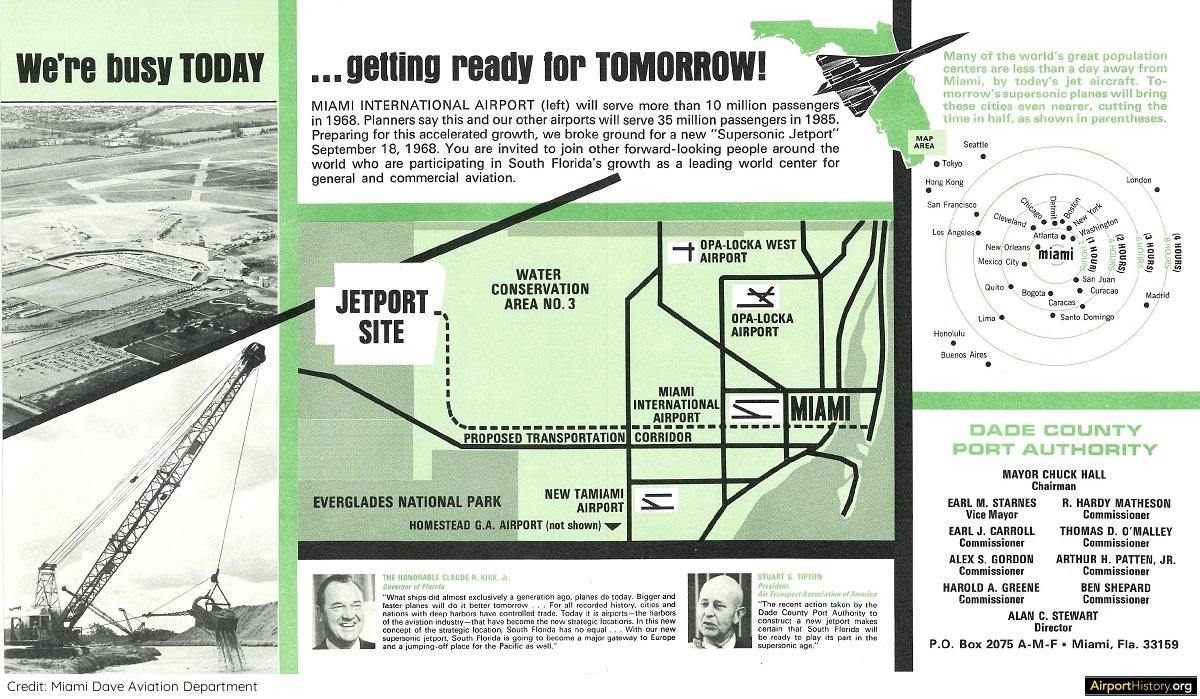

Miami, being the gateway to Latin America and a major base for long-haul Pan Am flights, was expected to become a major SST hub. Miami International Airport was located in the middle of built up areas and SST noise was expected become a major issue.

In 1968, the decision was taken to build a huge new airport in the Florida Everglades, which planners envisioned would become a major intercontinental SST hub. The “Everglades Jetport” would have been five times larger than New York’s Kennedy Airport.

The airport was planned to have six runways in its final layout and would be connected to Miami by an expressway and monorail line.

Initially, the Everglades Jetport would supplement Miami International Airport but in the long term it would replace it completely. After completion of the first 10,499-foot (3,200-meter) runway in 1970, construction was halted due to a scathing environmental impact report. Named the Dade-Collier Training and Transition Airport, the airport nowadays is used as an aviation training facility.

We will soon post a separate article about the Everglades Jetport as part of our “Never Built” series!

A November 1970 aerial of the only completed runway of the Everglades Jetport. After cancellation of the project the airport lived on as a training facility.

Snapshot from a 1968 brochure announcing the Everglades Jetport project. The airport would have had six runways in its final layout and would have been five times bigger than New York’s Kennedy Airport.

West Coast

LOS ANGELES

As the third largest US city at the time (now second largest), Los Angeles was surely to become a major destination for SST jets. Due to the location of LAX, noise considerations were also a major concern, even though most take-offs would have been over the ocean.

In 1968, the city started a search for suitable locations for a large-scale airport, which would supplement LAX and could accommodate SST jets.

One potential solution was the construction of an airport, two miles offshore, which could host SST operations without any noise problems.

Finally, however, planners chose to develop a new airport on a site near Palmdale, 62 miles (100 kilometers) north of Los Angeles. The city purchased 17,000 acres of land west of Air Force Plant 42, to develop what would be named Palmdale Intercontinental Airport, a mega jetport with four parallel runways.

Although a small passenger terminal opened in 1971, the scheme never came to fruition.

A separate article on Palmdale will be launched in the future as part of our “Never Built” series!

This Lockheed promotional image showed how a SST could park at one of LAX’s existing satellite buildings. Note that aircraft still parked parallel to the concourse.

An artist’s impression of the supplemental offshore airport serving LAX. The airport would be connected to the existing airport (bottom right) by means of a tunnel. The concept never got beyond the planning stage.

SAN FRANCISCO

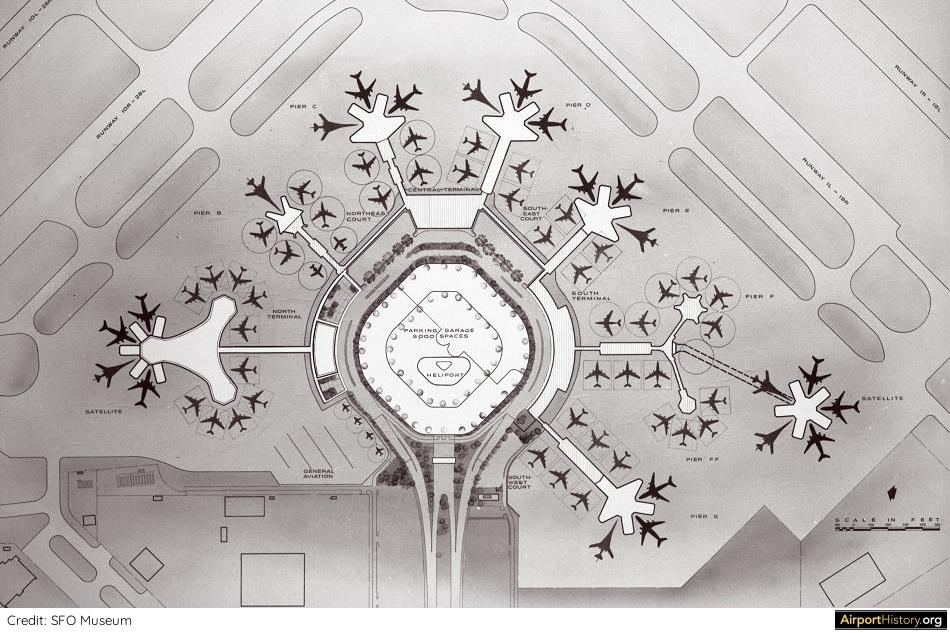

Being a major international gateway as well as a base for both Pan Am and TWA, San Francisco International Airport was projected to welcome significant SST traffic. This is evident in San Francisco International Airport’s 1967 draft master plan. Many of the stands on the newly built and reconfigured concourses show SSTs.

The master plan report mentions that the planners made a special trip to Boeing in Seattle to view the mock ups of the Boeing 2707 (as well as the 747) in order to obtain first-hand knowledge of the problems and possibilities of handling the new generation of aircraft.

Although SST noise was a concern, it was a bit less pressing than at other major airports around the nation. Due to its location bordering San Francisco Bay and its runway configuration, most SST flights would have been able to both land and take-off over the Bay.

A 1967 draft master plan for the future development of San Francisco International Airport. It’s evident that planners considered the SST in their plans with several stands being suitable for this new generation of aircraft. Can you spot them?

Mid-America’s jetports

HOUSTON, KANSAS CITY, DALLAS

Contrary to the coastal US cities, most cities in the Midwest and South had an abundance of space to build new airports.

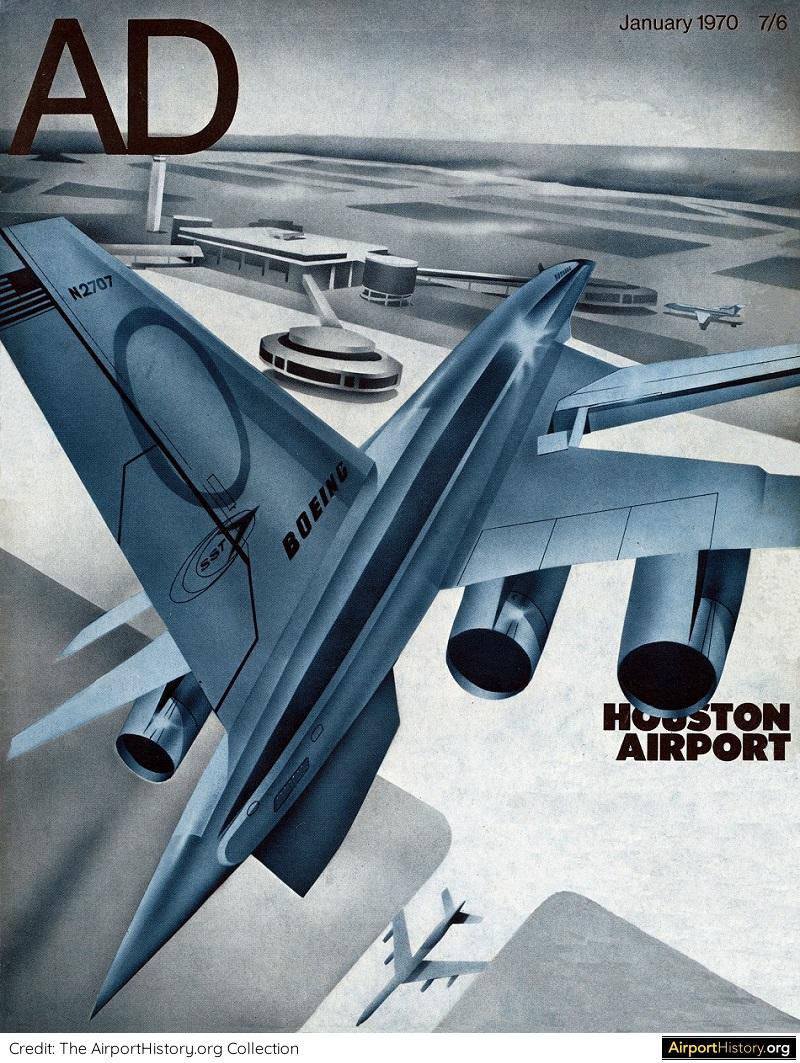

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, a new generation of large-scale ‘jetports’ opened in the American heartland: Houston Intercontinental (1969), Kansas City (1972) and Dallas-Fort Worth (1973).

They were designed in the mid-to-late 1960s, at the height of the SST hype and when air traffic was growing by 15% annually. These airports were located far way from the cities they served and had almost unlimited possibilities to expand.

In 1966, Dallas-based Braniff International Airways took an option on three Concorde aircraft. This is reflected in the 1968 DFW master plan, which indicates various stands with parked Concorde aircraft.

Many design decisions for the new Kansas City Airport–whose terminals bore a strong resemblance to those of Dallas-Fort Worth–were driven by TWA, who operated a major base there.

The airline envisioned the new airport as a major intercontinental hub serving the heartland, using its fleet of 747s and SSTs.

In the near future, we will post full histories on the old and current airports of Dallas, Houston and Kansas City!

The January 1970 issue of Architectural Digest presented the new Houston Intercontinental Airport as an airport for the supersonic age.

This 1973 print called “Airport of the Future” by artist Wilf Hardy shows an SST flying over the new Dallas-Fort Worth Airport. I wonder what ”AOL” stands for?

A Concorde is preparing to land (or crash?!) on this artist’s impression of the future Kansas City Airport, which was conceived as a intercontinental hub for TWA.

Canada

MONTREAL

In the late 1960s, at the height of SST development, the Canadian city of Montréal was one of North America’s most important international gateways–many inbound flights from Europe on their way to cities like New York, Chicago and Houston made a stopover at Montréal’s Dorval Airport.

The airport was quickly becoming saturated and planners started looking ahead. They assumed that traffic would grow with 15% annually into the foreseeable future and that the majority of people would be transported in SST aircraft.

Based on that assumption, it was decided to build a vast new airport one hour north-west of Montréal. In its final layout, the airport would boast six runways and six passenger terminals. A large buffer zone was established around the airport to ensure noise would never become an issue. The first phase of Montréal Mirabel Airport opened on October 4th, 1975.

A fantastic artist’s impression of Mirabel in the final layout. The airport would boast six runways, six passenger terminals and vast cargo and maintenance areas. The first terminal to be built was located in the top middle of the image.

Europe

Contrary to the American heartland and Canada, space in Europe comes at a premium. The development of large-scale greenfield airport projects is generally very difficult in Europe.

With the advent of the Jet Age and SSTs dominance on the horizon, several European capitals, such as London, Paris, Amsterdam and Copenhagen sought to build new airports.

LONDON

Similar to New York, London was slated to become one of the busiest SST hubs. In 1964, the UK’s long-haul flag carrier BOAC (later British Airways) declared the intention to buy eight Concorde aircraft.

Heathrow, London’s primary airport, was located in the city’s western suburbs and aircraft noise was becoming a major concern. In addition, with traffic booming in the 1960s, both Heathrow and Gatwick were thought to reach capacity well before the end of the century. Hence, the construction of a third London airport was deemed necessary.

In 1971, the government selected Maplin Sands, located in the Thames Estuary, as the location for a new four-runway airport. With takeoffs and landings taking place over open water, London Maplin, would have offered an effective solution for the SST noise issue.

However, in late 1973, the Maplin scheme was abandoned due to rising construction costs and falling passenger demand due to the oil crisis.

We’ll be publishing a separate article on the search for a third London airport in the near future.

A rare artist’s illustration of the unbuilt London Maplin Airport, which was planned to be built on reclaimed land in the River Thames estuary.

PARIS

Similar to New York and London, Paris was bound to see plenty of SST operations. In 1964, Air France, declared the intention to buy eight Concorde aircraft. Air France’s home base, Paris Orly Airport, was nearing capacity and was located in the middle of built up areas, making it unsuitable for the operation of noisy SSTs.

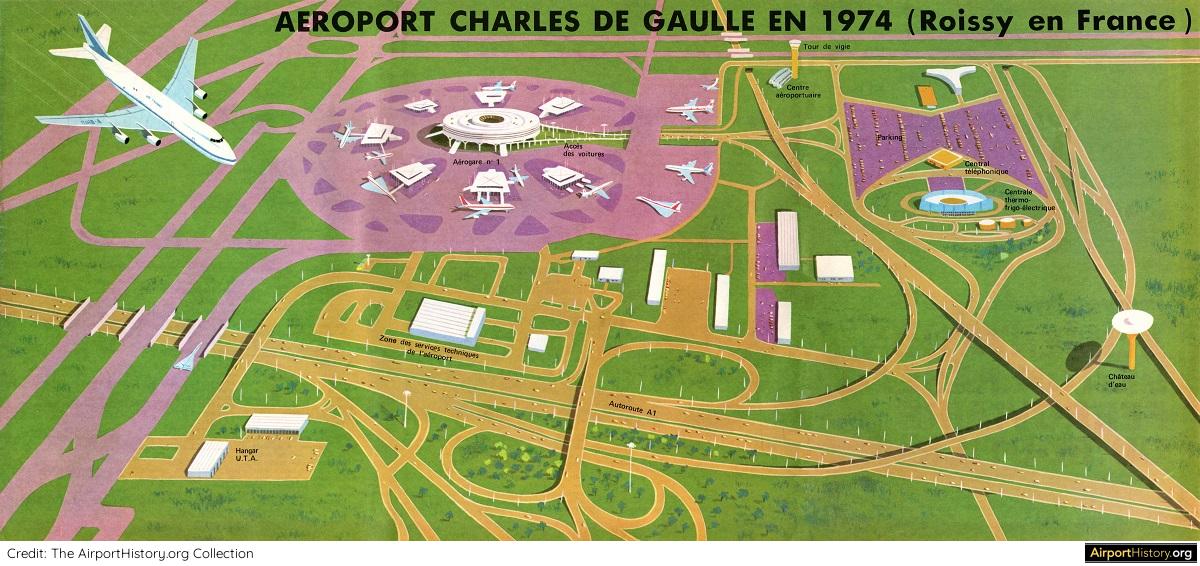

In 1964, the French government gave the green light to build a new Jet-Age airport north-east of Paris. Planning work on Roissy Airport, named after a nearby village, started in 1966, when it seemed sure that 747s and SSTs would soon rule the skies.

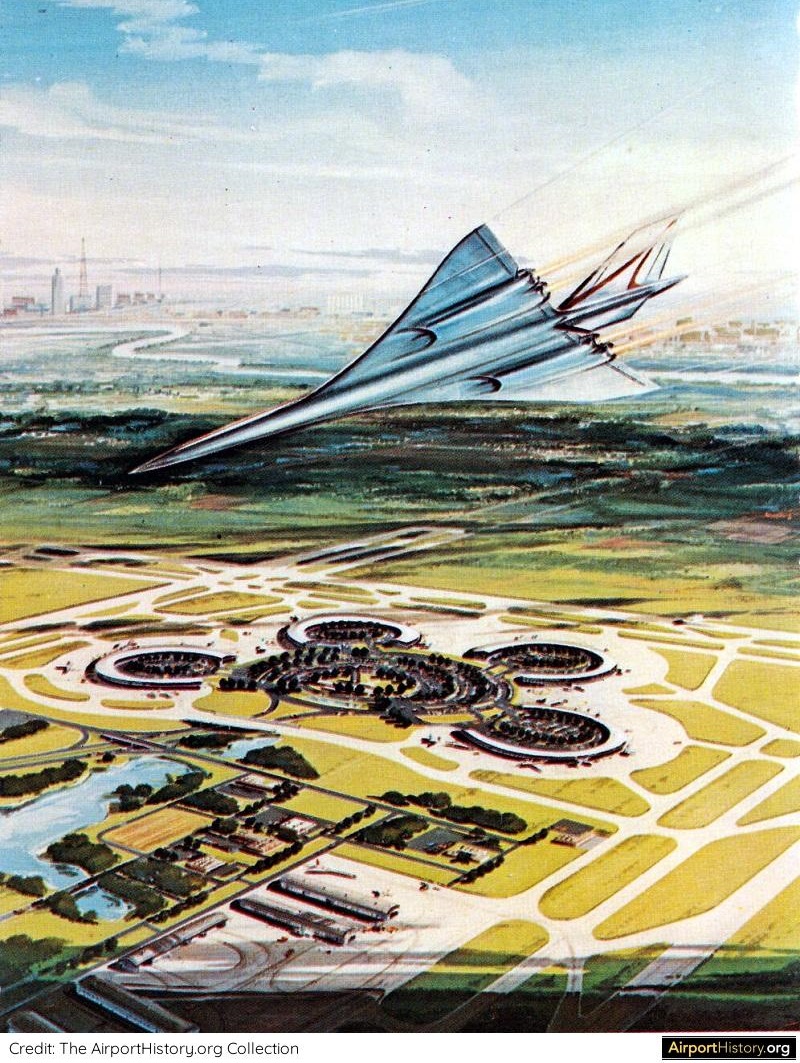

In its final layout, the airport would boast five runways and five massive, futuristic, round terminal buildings, the perfect setting for the SSTs. Seemingly to match the high speeds in the air, the airport’s design was optimized for high-speed circulation, loading and unloading of aircraft. Roissy, renamed Paris Charles de Gaulle Airport, opened for service in March, 1973.

A fantastic artist’s impression of Phase 1 of the “future” Paris de Gaulle Airport, an airport that was designed with both SSTs and 747s in mind.

South America

RIO DE JANEIRO

In the late 1960s and 1970s, Brazil enjoyed very high rates of economic growth. People started to speak about the “Brazilian miracle”. During this period, the government made large scale investments in infrastructure and industry.

It’s within this context that in 1967, a study into the large-scale expansion of Rio’s Galeão Airport was commenced. As Brazil’s major tourist hub, Rio de Janeiro was expected to see its fair share of SST service. The government engaged Aéroports de Paris–the same organization that designed the brand new Paris de Gaulle Airport–to design a state-of-the-art gateway to Brazil.

The expanded Galeão Airport, called “The Supersonic Airport”, opened in 1977, almost three years behind schedule.

An artist’s impression of the expanded Galeão Airport. If you look closely however, you can count four Concordes on the ground. Note the similarity of the taxiway design to that of Paris de Gaulle.

To be concluded in Part 2!

Click here for Part 2, where we will continue the supersonic story and see how things actually worked out for the SST and how SST service was at airports around the world!

Share your thoughts on this article below!

Trackback from your site.