Written By Joseph Wolf

Part I: The facts

Before the merger:

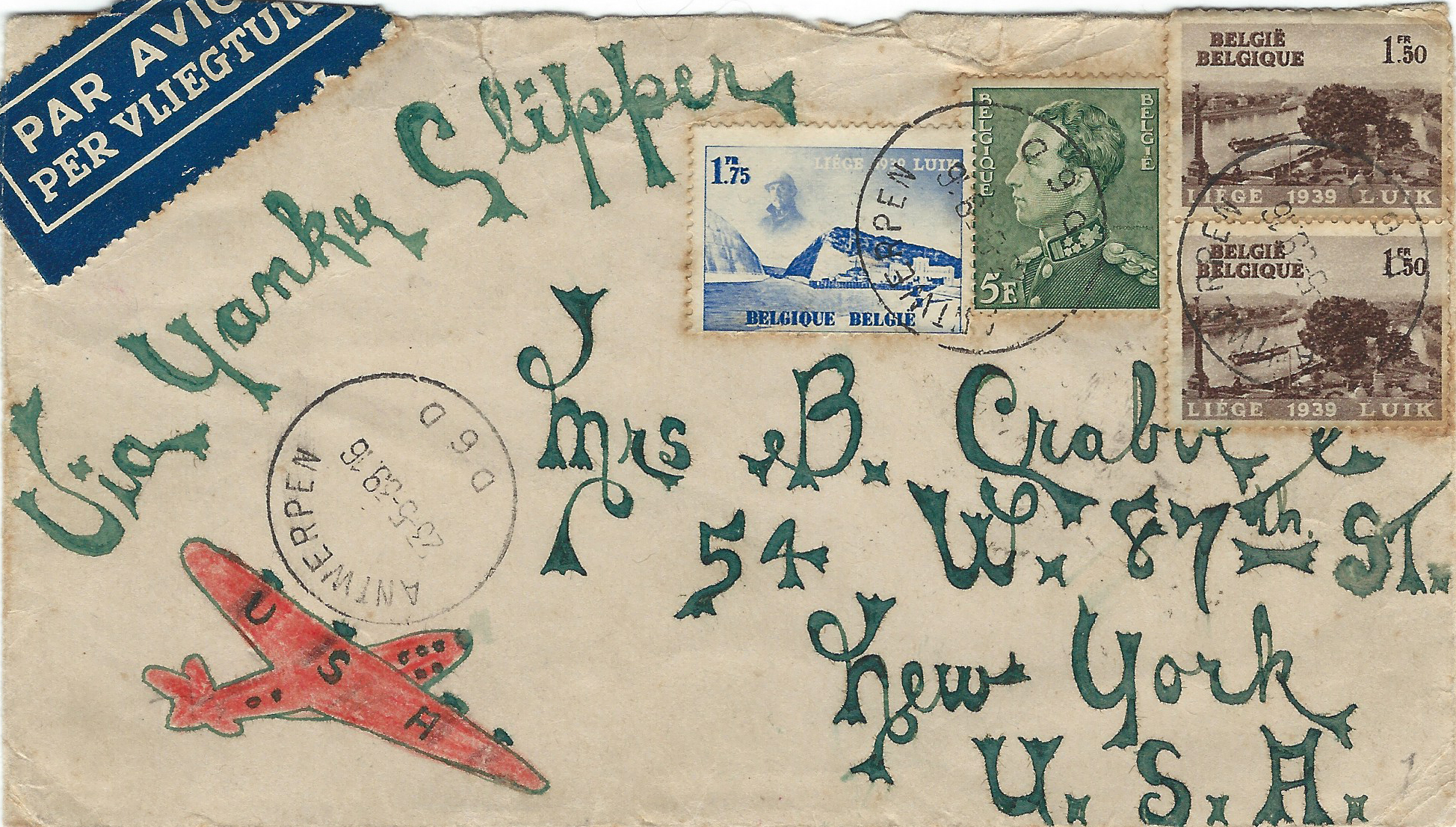

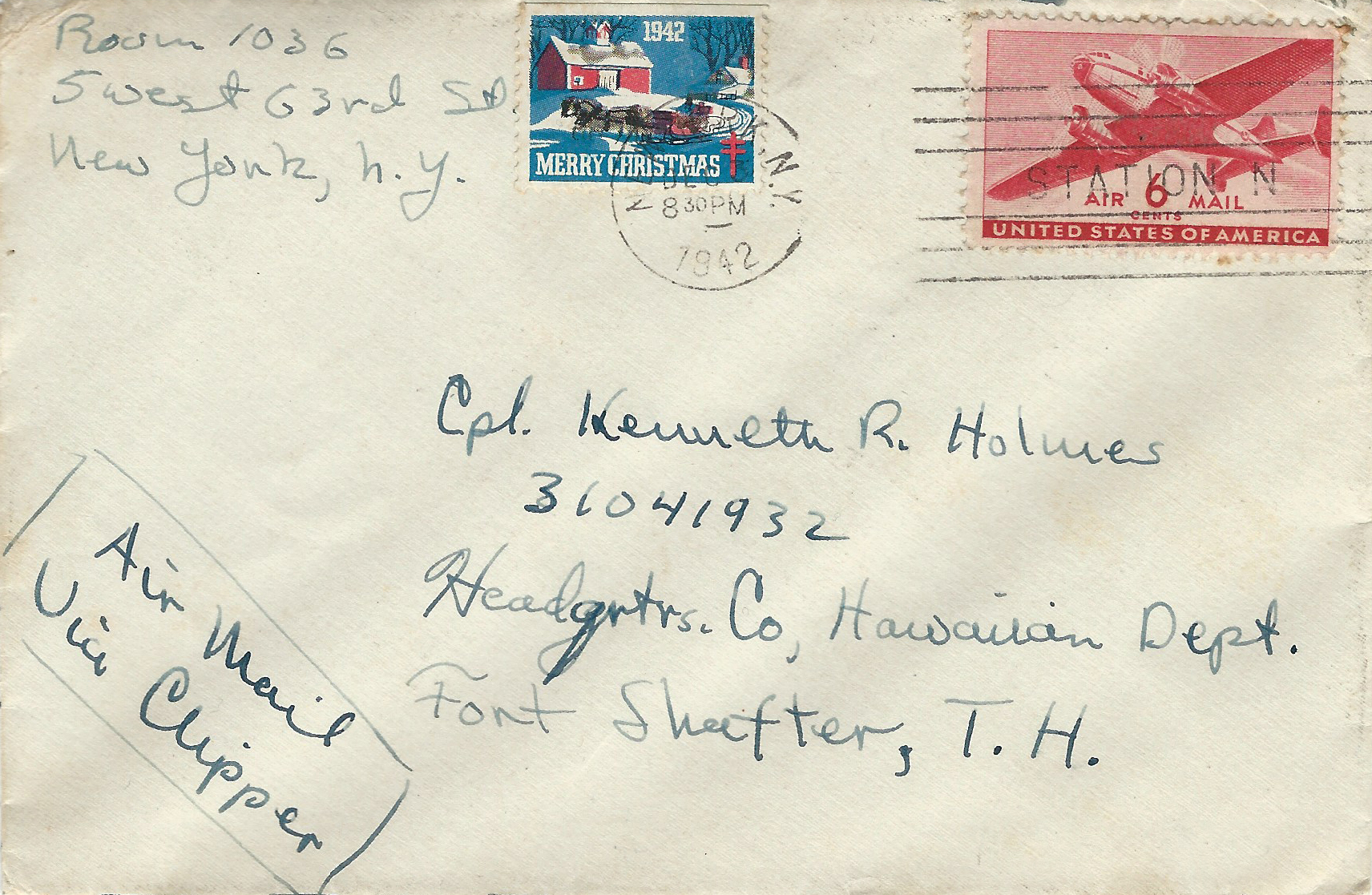

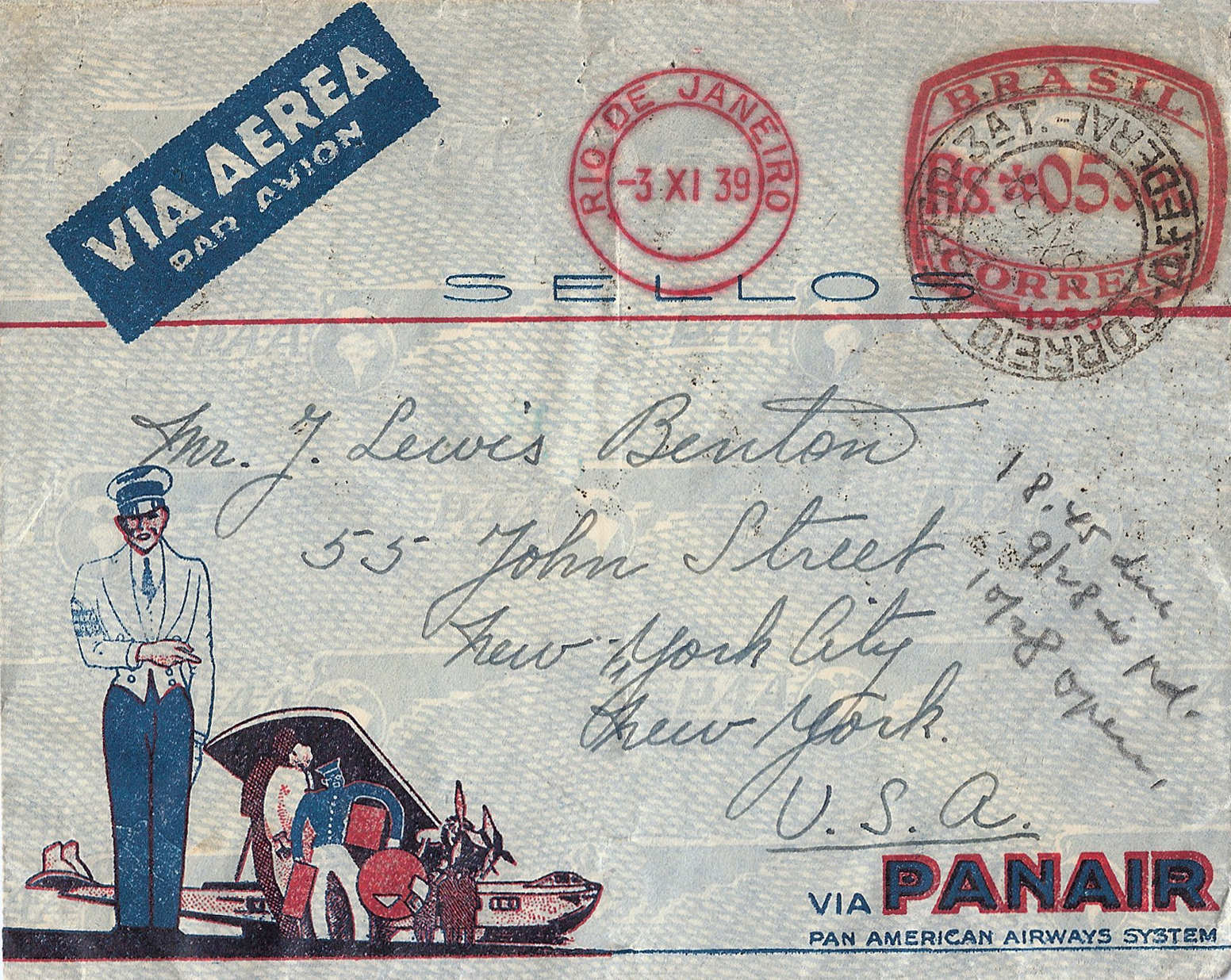

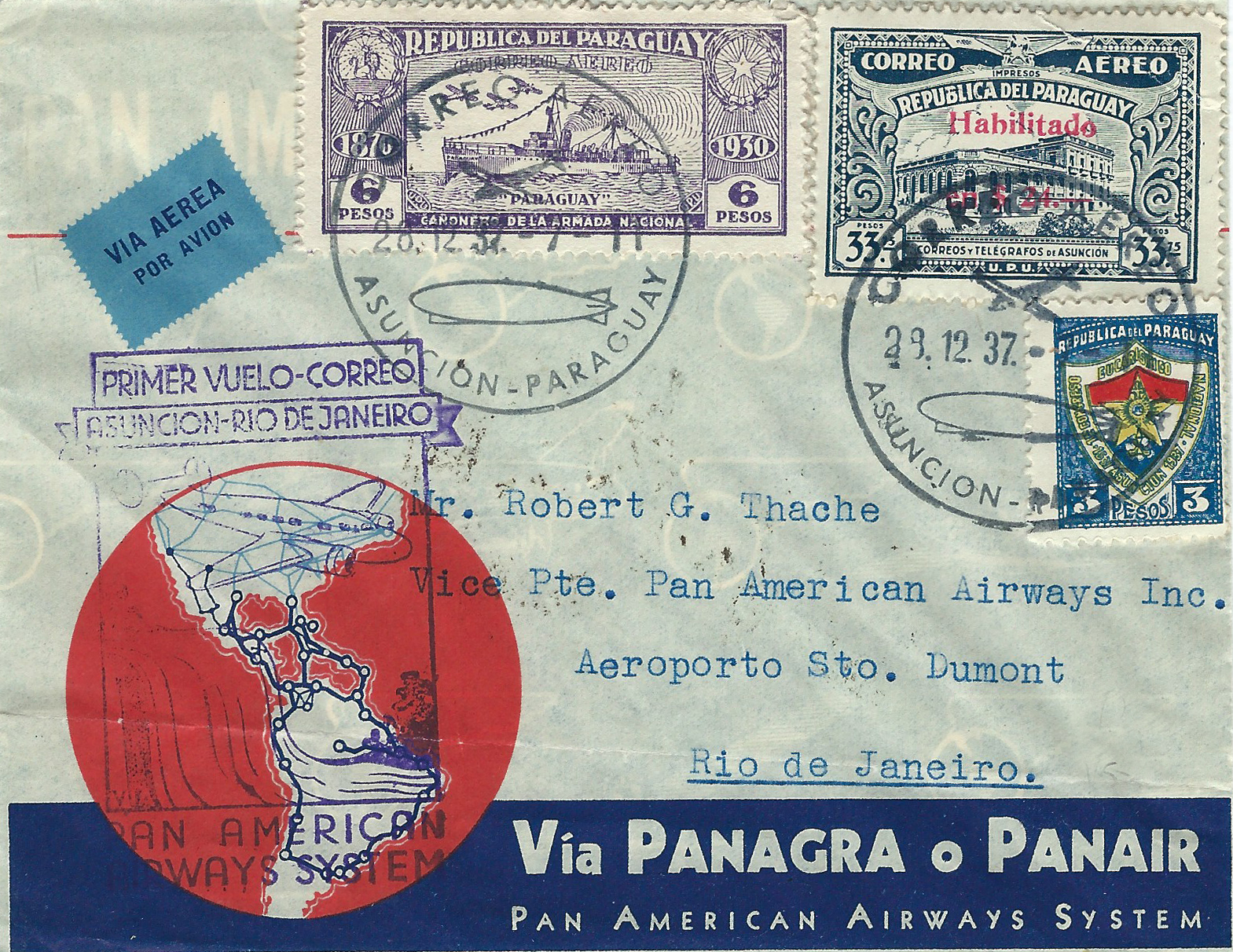

Pan American World Airways was America’s airline to the world for many years. Pan Am pioneered international air travel, first through Latin America in the late 1920s and early 1930s, then across the Pacific in 1935, and across the Atlantic in 1939. After World War II, Pan Am replaced the flying boats used on their initial trans oceanic flights with land planes, inaugurated around the world service, and steadily expanded the number of destinations they served, both in the US and abroad. The 1960’s were Pan Am’s apogee, as the lower operating costs and tremendous speed of Pan Am’s 707s and DC-8s enabled Pan Am to reduce the costs of international travel enough that it became possible for everyone, not just the very wealthy, to travel abroad.

However, Pan Am made a serious mistake in the late 1960s by ordering 25 Boeing 747s, based on the assumption that international travel would continue to grow at 15% per year indefinitely, and jet fuel prices would remain low. When the economy went into a recession just as the 747 was entering service, the costs of flying almost-empty 747s around the world caused Pan Am to hemorrhage money.

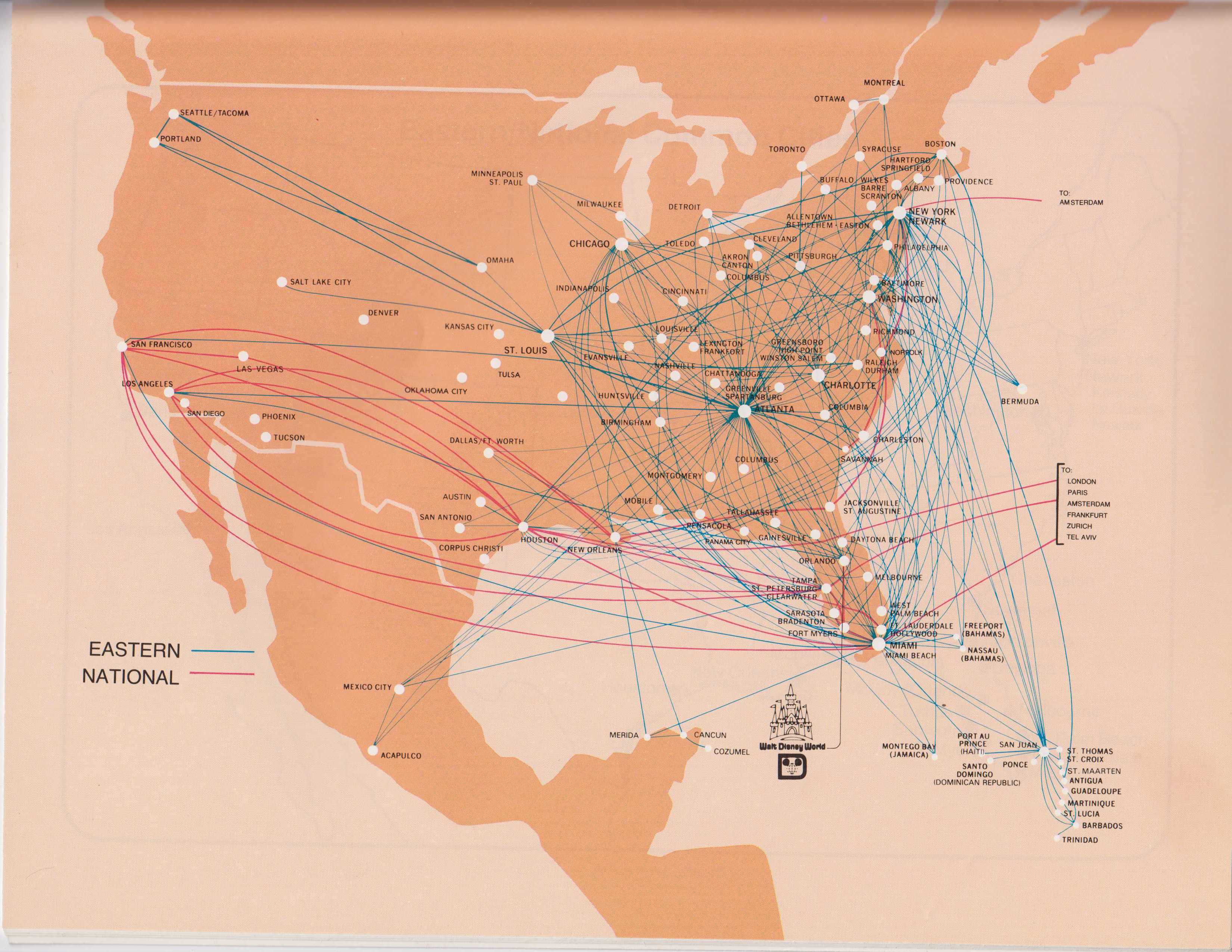

Another reason for Pan Am’s losses in the 1970s was that they had no routes within the continental US, and had to rely on feed from American, United, Eastern, and other domestic airlines. Pan Am had applied for routes within the continental US several times, but had consistently been rebuffed by the US Government.

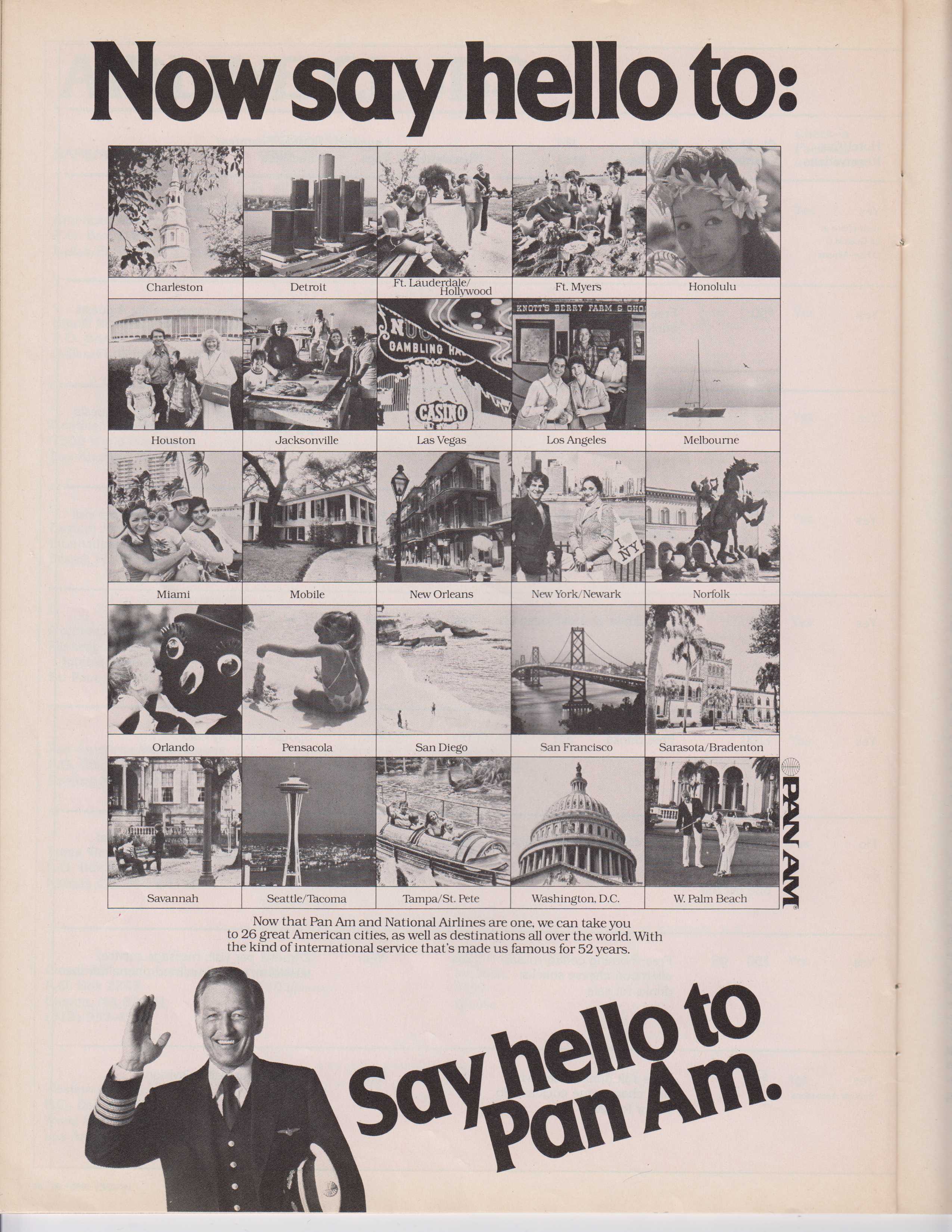

For many years, Pan Am had wanted to buy National Airlines, which linked Pan Am’s main gateways of New York City, Miami, Los Angeles, and San Francisco.

National had been founded in 1934. National’s first route was from Tampa to Jacksonville, and National operated within Florida for the first years of its existence. During World War II, National’s aggressive president George Baker won a route up the East Coast to New York City and Washington DC, via important naval bases such as Savannah, Charleston, and Norfolk. After the war ended, National beat arch rival Eastern by offering the first flights between New York and Miami with modern DC-4s. In the 1950s, National’s routes were gradually extended westward to Houston, then in 1961, National became a transcontinental airline with a further extension to California.

National profited immensely from the “race to the moon” in the 1960s because they were the only airline with direct flights between Los Angeles (where much of the work on the Apollo space capsules took place), Houston (home of Johnson Space Center) and Cape Kennedy. National marketed itself, with great success, as a more glamorous alternative to stodgy rival Eastern Air Lines with slogans like “Airline of the Stars” and “Fly Me”, and emphasized their Florida home by painting their aircraft with orange and grapefruit colored stripes. In 1970, National was chosen over Pan Am and TWA for a Miami-London nonstop, becoming the US’s third transatlantic airline.

However, National’s fortunes declined in the 1970s. Like Pan Am (and many other airlines), National purchased too many wide bodied aircraft in anticipation of a traffic boom that never arrived. National’s president Bud Maytag, who had purchased a large stake in National from George Baker shortly before Baker’s death in 1963, took a hard line on controlling costs, which resulted in the airline being shut down by strikes nearly every year in the 1970s. After ailing Northeast Airlines, which had been awarded routes from Boston, New York City, and Washington to Florida in 1956 in competition with National and Eastern, was taken over by Delta Air Lines in 1972, Delta’s aggressive management and reputation for outstanding customer service caused Delta to take substantial market share from National. In the early 1970s, National and Northwest Airlines agreed to merge, but the merger was called off after quick approval from the US Government was not obtained.

National operated joint flights between New York City and South America with Pan Am and Pan American Grace Airways (Panagra) in the 1950s and 1960s, with National crews flying South America-bound aircraft from New York City to Miami, Pan Am crewing the aircraft from Miami to Panama City, and Panagra operating the rest of the way. In 1958, Pan Am and National agreed to forge even closer ties, when National agreed to give Pan Am the right to purchase enough stock to control National in exchange for Pan Am leasing 707s to National every winter. The transaction enabled National to become the first airline to fly jets within the United States. In the summer of 1960, the US Government disallowed the transaction. It was widely believed National’s management expected the transaction to be disallowed, and only agreed to it in order to be able to offer pure jet service more than a year before arch rival Eastern Air Lines could do so. Although this merger attempt was disallowed, Pan Am’s interest in acquiring National never went away.

The merger:

In 1969, financier Francisco (“Frank”) Lorenzo took over local service airline Texas International. Lorenzo and his aggressive management team suspended service to many of the smaller communities the airline served, and turned it into a regional airline serving Texas and neighboring states. Texas International also used low promotional fares to increase traffic and steal passengers from rival airlines.

In 1978, Texas International began purchasing stock in National, in hopes of taking the airline over. At the time, National’s stock price was just $17 per share, and the cost to buy all of the airline’s stock was less than the value of the airline’s fleet of relatively new 727-200s and DC-10s.

Once Texas International’s desire to merge with National became known, Pan Am realized that unless they acted quickly, they would lose the chance to merge with National. Pan Am proposed a merger with National, and offered $41 per share. Unlike Texas International, Pan Am’s interest in National was openly welcomed by National’s management.

A few weeks later, a third bidder for National emerged: Eastern Airlines. Although Eastern and National had been competitors for many years between the northeast and Florida, after deregulation National significantly reduced their flights in this area in order to focus on their more successful southern transcontinental routes from California and Nevada to Texas, Louisiana, and Florida. Eastern wanted to merge with National to obtain the southern transcontinental routes, as well as National’s profitable routes from Florida to Europe. Eastern offered to purchase National for $50 / share.

After several months of negotiations, Texas International agreed to support Pan Am’s bid for National, and sell to Pan Am the 23% of National stock Texas International had acquired, in exchange for Pan Am raising their offer for National’s stock to Eastern’s higher bid price. Pan Am and National officially merged in January, 1980.

The aftermath:

The merger of Pan Am and National was disastrous for Pan Am. As part of the process of combining the two airlines’ workforces, Pan Am agreed to increase the wages of National’s unionized employees to the much higher salaries earned by Pan Am’s staff, which meant that flights that were profitable at National’s low cost levels became unprofitable at Pan Am’s higher costs. Unrest in the Middle East caused oil prices to rise substantially in the late 1970s, which increased the costs of the merged Pan Am / National further. A substantial rise in interest rates in the late 1970s and early 1980s made the merged airline’s financial situation even more dire; Pan Am was heavily indebted before the merger because of the expenses to purchase the airline’s 747s, and borrowed even more to pay for National and a fleet of L-1011-500s that was intended to replace Pan Am’s 707s.

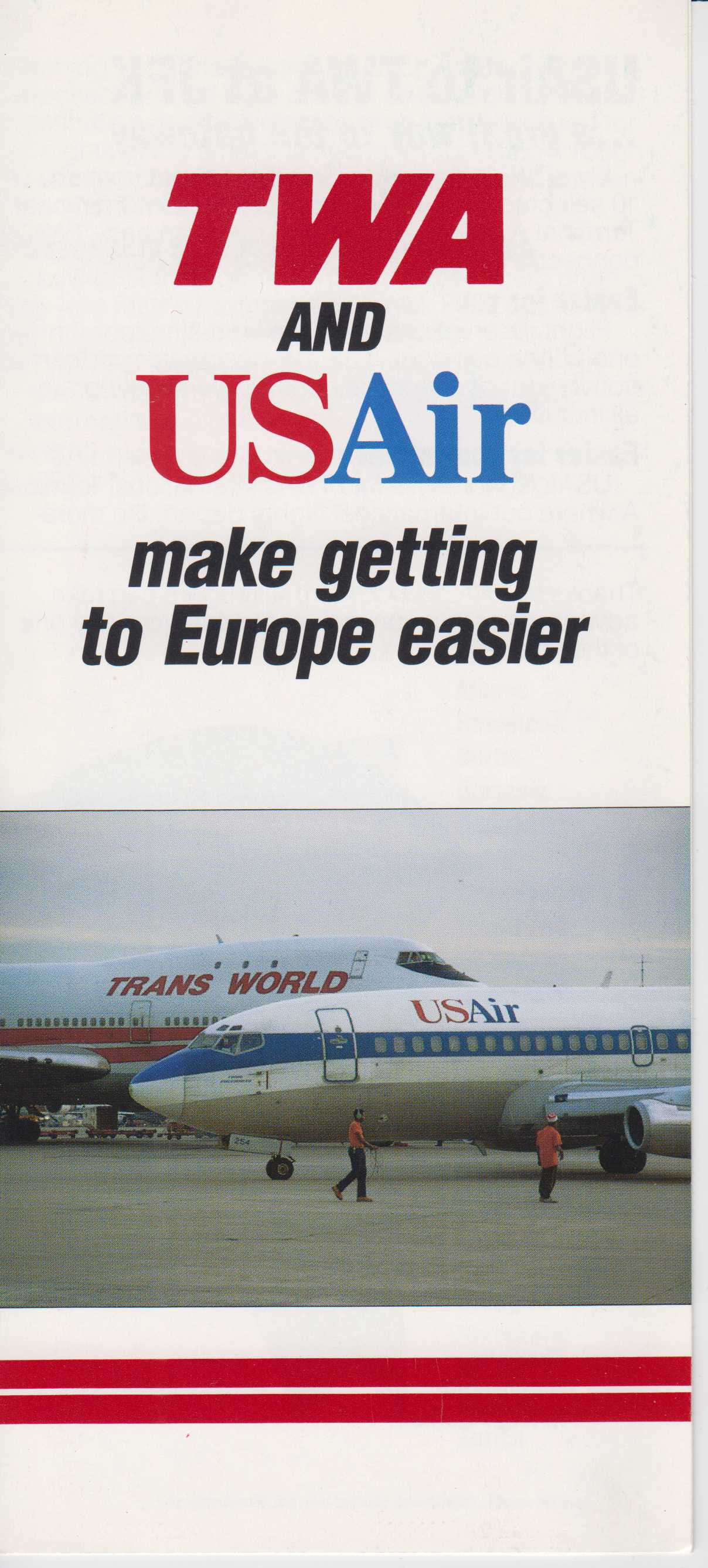

Pan Am also made a crucial strategic error as part of the merger process. After a large addition to Pan Am’s terminal at JFK opened in 1973, Pan Am leased several gates in the original 1960 “round” portion of the terminal to Allegheny, as part of a joint marketing campaign where passengers traveling between the Northeast and Europe, the Caribbean, South America, and Japan were encouraged to take Allegheny to New York City, then Pan Am the rest of the way. In the summer of 1979, Allegheny and Allegheny Commuter operated 30 flights to 10 cities from Pan Am’s Worldport.

National Airlines for many years operated out of a temporary terminal at JFK. In 1969, National opened a massive new terminal, called the “Sundrome”, which was much too big for National’s needs; in the spring of 1979, just 17 flights a day operated out of the Sundrome’s 12 gates. After the merger, the two airlines consolidated operations at Pan Am’s terminal, Pan Am ended its partnership with Allegheny (soon to be re named USAir) and sold the Sundrome to TWA, whose terminal at JFK was next to the Sundrome. USAir moved to TWA’s original terminal at JFK, and began encouraging Europe bound passengers to take USAir to New York City, then TWA, not Pan Am, the rest of the way. Effectively, Pan Am had chosen to relinquish to TWA high fare business travelers who worked for companies like Kodak, Eli Lilly, and US Steel based in cities on Allegheny / USAir’s routes, in exchange for low fare vacationers going to Florida on National’s old routes, while also giving TWA the opportunity to use the additional gates at the Sundrome to substantially expand TWA’s routes from New York City.

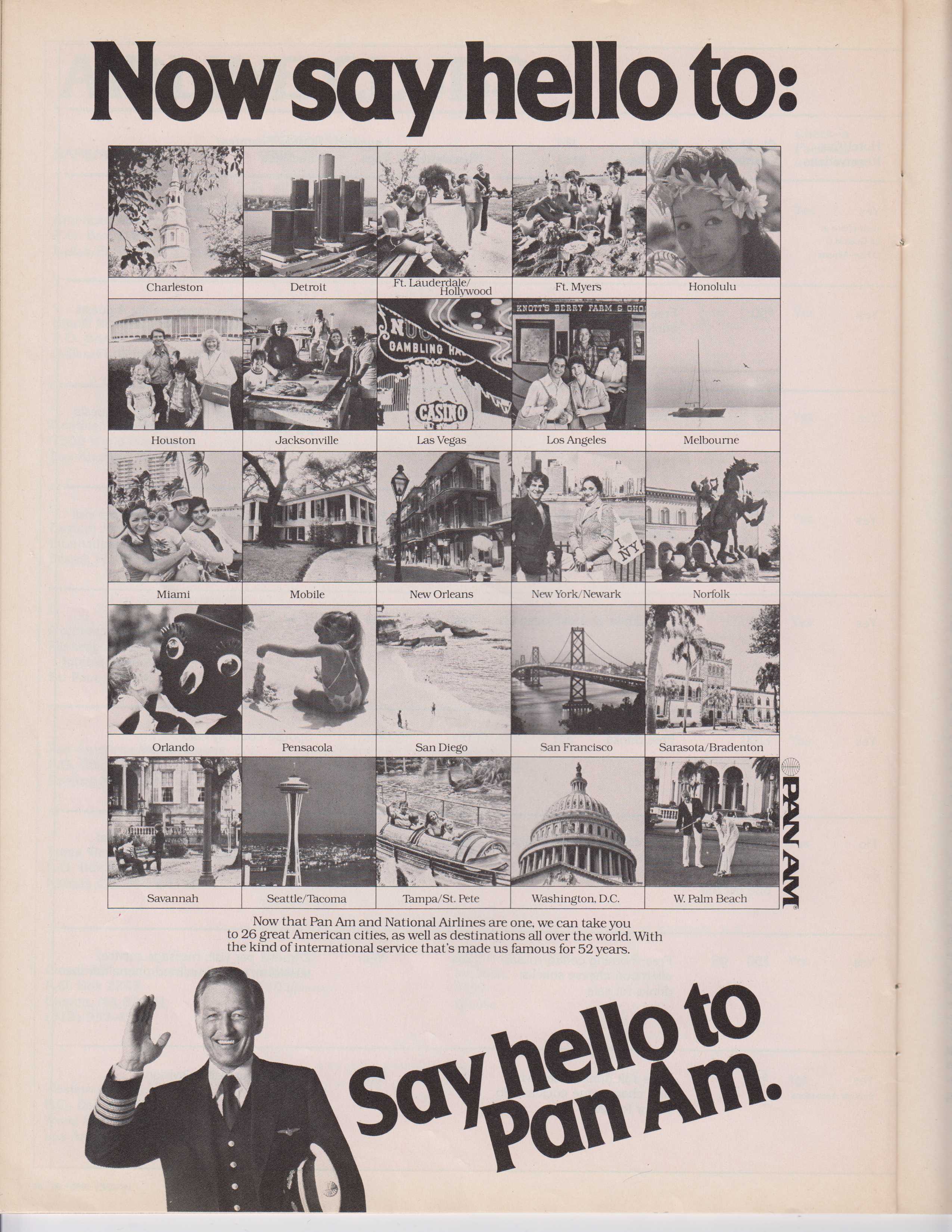

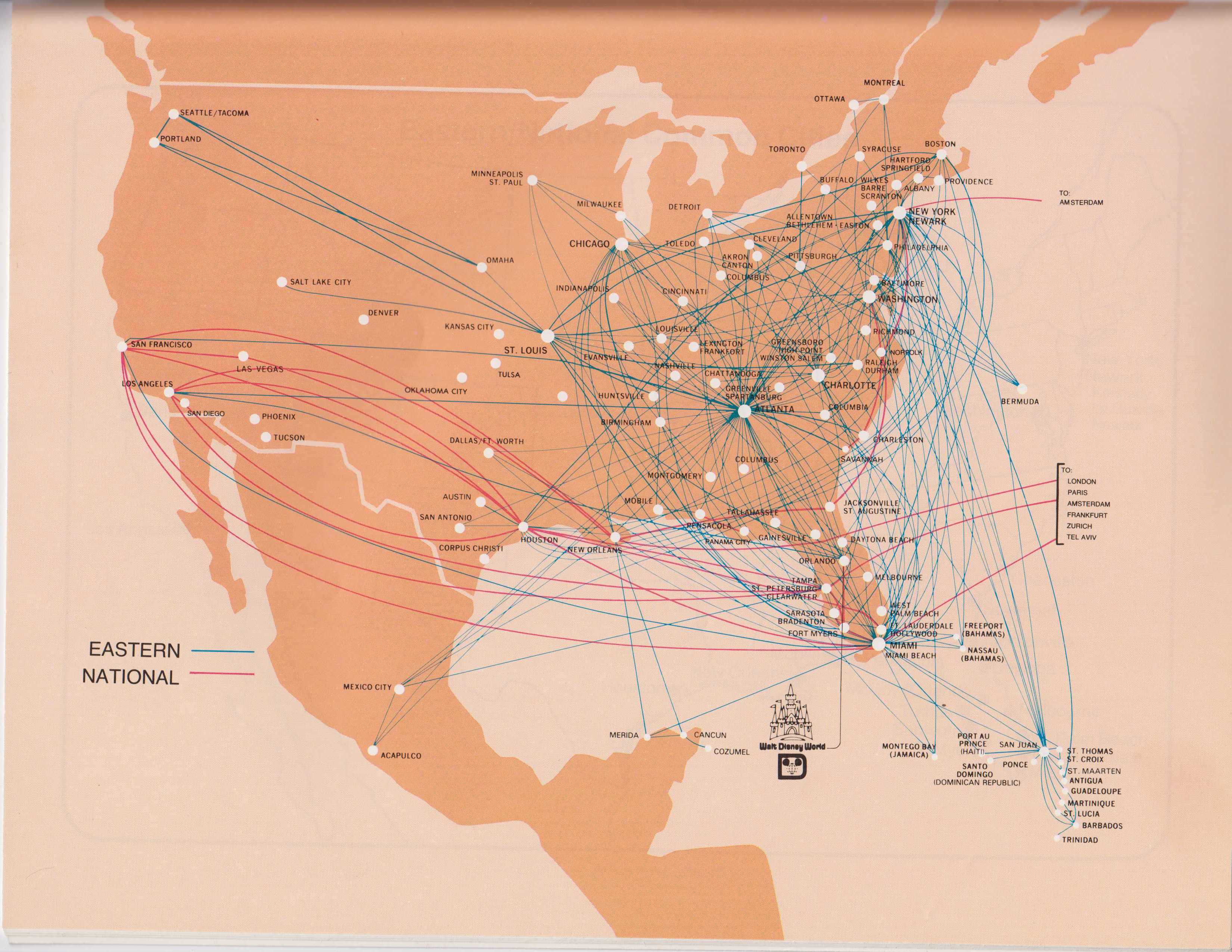

Another flaw in the Pan Am / National merger was that, although National served Pan Am’s main gateways of New York City, Miami, Los Angeles, and San Francisco, the destinations on National’s route system that were not served by Pan Am were mainly leisure oriented cities like Tampa, Las Vegas, and New Orleans that in the 1970s generated few international travelers. The merged airline did not serve cities like Atlanta, Chicago, St Louis, Minneapolis, or Cincinnati that have large numbers of people who need to travel overseas on business; the only city in the US Midwest on the merged airline’s route system was Detroit, which was served by Pan Am but not National before the merger. The main rationale for the merger was that National’s domestic routes were supposed to feed Pan Am’s international flights, but a simple glance at the two airlines’ route systems would have shown how little feed National could provide.

While Pan Am struggled to integrate National, other airlines, ranging in size from TWA to new entrants like Air Florida, aggressively attacked the merged airline’s routes between the northeast and Florida with low fares that further increased Pan Am’s losses. Texas International used its profits from selling National stock to Pan Am toward the purchase of Continental Airlines, and the combined Texas International + Continental attacked Pan Am + National’s routes from Houston to Florida and California. Within four years after the merger, Pan Am had suspended most former National routes, and sold National’s fleet of DC-10s to American. Fortune Magazine subsequently named the Pan Am / National merger to its list of the seven worst mergers of the 1970s. The heavy debt from acquiring National did not go away after National’s routes were suspended by Pan Am, and was one of the main factors that led to Pan Am’s shutdown in 1991.

Part II: What If Texas International had acquired National?

It’s pretty clear that, in Pan Am’s haste to beat out Texas International for National, Pan Am didn’t step back and objectively look at how little feed National could provide Pan Am; nor did Pan Am consider the costs of merging the two airlines’ work forces. What would have happened if Pan Am had considered these risks, and chosen to step back and let Texas International purchase National?

A merged Texas International / National would have been formidable. Texas International had a strong presence in Houston, with routes to 19 cities. National flew to 10 cities from Houston, just one of which, New Orleans, was also served by Texas International. Many of the cities served by Texas International were business oriented destinations like Baltimore and St Louis, while National was strongest to Florida, which would have given the combined airline a good mix of business and leisure routes. The merged airline would have had a modern fleet; Texas International flew DC-9-10s and -30s, and National flew mainly DC-10s and 727-200s.

National was one of the two lowest cost airlines in the 1970s (along with Northwest) thanks to Bud Maytag’s years of confrontation with the airline’s unions. A merger with equally low cost Texas International would not have increased the combined airline’s labor costs the way National’s merger with high cost Pan Am did, so the merged airline would have had a very low cost structure.

In the first year or two after the merger, Frank Lorenzo would probably have focused on integrating the airlines’ work forces and fleets, with National’s DC-10s taking over Houston-Mexico City from Texas International’s DC-9s, and National’s 727-200s taking over other major Texas International routes like Houston-Denver and Dallas-Las Vegas, while Texas International’s DC-9s could have been redeployed on some of National’s shorter routes like New Orleans – Mobile – Pensacola. Frank Lorenzo would have built Houston into a large hub, just as he did after purchasing Continental a few years later.

However, Frank Lorenzo would also almost certainly have done things outside Houston that would have had a major impact on the post-deregulation airline industry. At the onset of deregulation, Texas International was very aggressive at stimulating demand for air travel, and growing market share, by offering low fares. As mentioned earlier, after deregulation National reduced their presence on routes between the northeast and Florida. The merged airline would have aggressively lowered fares on these routes, to grow the northeast-Florida air travel market and take existing customers from Eastern and Delta, with National’s fleet of DC-10s.

After the two airlines were fully consolidated, it’s also likely that the merged airline would have looked to the very large market for air travel between Florida and Midwest cities like Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Detroit, Chicago, Minneapolis, and St. Louis. People in the Midwest prefer Florida’s Gulf coast, and National had an underutilized terminal at Tampa capable of accommodating DC-10s that could easily have been used to offer low fare flights to Midwestern vacationers.

It’s also worth considering what the merged airline would have done with National’s Sundrome terminal at JFK. Even if the merged airline had aggressively rebuilt National’s presence in the New York City-Florida market, it would have only needed about 1/3 of the Sundrome’s gates. Perhaps they would have sold it to TWA, as Pan Am did, then subleased the few gates they needed from TWA, or even moved to United’s underutilized terminal. Another intriguing possibility, though, is that the merged airline might have used the Sundrome to build a low fare hub at JFK, just as jetBlue did at the Sundrome two decades later. Frank Lorenzo created a separate airline, New York Air, to offer low fare service from LaGuardia and Newark to cities in the Northeast and Midwest, and later Florida, but a shortage of slots and gates at LaGuardia limited New York Air’s growth. The empty gates at the Sundrome would have been an ideal resource for the merged airline and / or New York Air to offer low fare service from New York City to far more cities than New York Air was able to serve from LaGuardia.

Given the creativity of Frank Lorenzo and his staff, it’s clear that if Texas International had taken over National, they would have made much better use of National than Pan Am did, and built it into a major airline with hubs in Houston, Miami, Tampa, and possibly JFK.

If Texas International had merged with National, the post-deregulation history of the US airline industry would have been different in several other ways, including:

- If Texas International had merged with National, they would probably not have attempted a hostile takeover of Continental in 1981, because National, not Continental, would have been the airline Texas International used to become a major carrier.

- National’s costs were much lower than Continental’s, so Frank Lorenzo would not have needed to use bankruptcy to break the merged airline’s unions and abrogate its labor contracts. One of the ugliest confrontations between airline management and unionized airline employees, the 1983 Continental Airlines pilot strike which led to the airline’s striking pilots being terminated by Lorenzo, would never have happened.

- Continental Airlines had agreed to merge with Western Airlines when Frank Lorenzo took over Continental. Without the interference from Texas International’s hostile takeover, a Continental + Western merger would have occurred. By the time of a Continental + Western merger, competition from the merged Texas International + National would have caused Continental to reduce their presence in Houston. However, both Continental and Western had very strong presences in Denver in 1981.

- Western was smaller than United, Continental, and Frontier at Denver. After their merger with Continental fell through, Western chose to shift their hub from Denver to Salt Lake City, where Western would be able to be the dominant airline. Had the Continental / Western merger gone through, the merged airline would have kept their hub in Denver, and Salt Lake City would not have become a hub unless another airline chose to build a hub there.

- As will be seen later in this article, a merged Texas International / National would have had a devastating impact on Eastern. When Eastern came up for sale, Texas International + National would not have purchased Eastern because of the overlap between Texas International + National and Eastern’s route systems. This, in turn, would have meant that the confrontations between Frank Lorenzo and Eastern’s unions would never have happened.

- Shortly before the merger negotiations, National signed a lease for half of Los Angeles’ planned Terminal 1, with PSA occupying the other half. The merged Pan Am / National remained in LAX’s international Terminal 2, with the gates intended for National in Terminal 1 ultimately being used by Air Cal, Muse Air, Southwest, and other low fare airlines. A merged Texas International / National would have moved to Terminal 1 when it opened in 1984, which in turn would have made it much more difficult for low fare airlines like Southwest to get gates in Los Angeles.

Part III: What about Eastern?

Railroad historian George Drury described the merger between New York Central and the Pennsylvania Railroad as being like “a late in life marriage to which each partner brings a house, a summer cottage, two cars, and several complete sets of china and glassware – plus car payments and mortgages on the houses”. A merger between Eastern and National would have been every bit as disastrous as the merger between the New York Central and Pennsylvania Railroad was. When Eastern bid for National, they were deeply in debt and had a large fleet of L-1011s that were too big for the airline’s routes. Eastern had also just made a multi billion dollar commitment for large fleets of A300s and 757-200s. A merger with National would have further increased Eastern’s crushing debt burden, and given Eastern a large fleet of DC-10s that they did not need. Eastern would also have been responsible for paying for National’s underutilized Sundrome, and National’s large overhaul base in Miami across the runway from Eastern’s maintenance complex. Eastern’s labor costs, like Pan Am’s, were among the highest in the airline industry, and increasing the salaries of National’s lower paid staff to Eastern’s higher compensation levels would have been a serious cash drain on a merged National + Eastern.

However, costly as a merger with National would have been for Eastern, the impact of a merged Texas International + National would have been nothing short of apocalyptic. As mentioned above, a merged Texas International + National would have aggressively cut fares and added flights not just on routes from Florida to the Northeast, but also on routes from Florida to the Midwest, and would also have added flights from the merged airline’s Houston hub to New York City and elsewhere in the northeast. Because Eastern was the dominant airline from the northeast and Midwest to Florida, and from the northeast to Houston, much of Texas International + National’s growth in these markets would have come at Eastern’s expense.

It’s clear that the Pan Am + National merger, followed by Pan Am’s abandonment of most of National’s routes, was the best case scenario for Eastern. Even with this best case scenario, Eastern’s heavy debt load and the impact of the recession that began in 1979 caused Eastern to be in serious financial trouble by the early 1980s. From 1980 to 1984, Eastern lost $380 Million ($1 Billion in today’s dollars), even more than Braniff lost in the three years before they shut down. Had Eastern been burdened with either the additional debt from a merger with National, or a loss of traffic from a merged Texas International + National, Eastern’s financial problems would have been much more desperate. Eastern narrowly averted default in 1983, and if their losses had been even 15% higher due to competition from a merged National + Texas International, or the debt from purchasing National, they could have been forced into bankruptcy.

PART IV: What would Pan Am have done had they not “gone National”?

Buying National Airlines was not the right solution to Pan Am’s need for domestic routes, but had Pan Am not bought National, they would have needed to address it somehow. One approach would have been for Pan Am to create a domestic US route system by purchasing 727-200s, establishing stations in interior US cities like Atlanta, St Louis, and Minneapolis, then flying the 727-200s from these cities to Pan Am’s coastal international gateways. This is the approach Pan Am took in the mid 1980s using National’s 727s after Pan Am abandoned most of National’s routes, but, as Pan Am discovered, it would have been very costly because Pan Am would have had to pay for gates, ticket counters, and employees to serve just a few flights a day at each interior city. Ultimately, the costs of establishing a domestic US feeder system would probably have been about as expensive as buying National was, and, when added to Pan Am’s heavy debt burden, would probably have sunk the airline just like the National merger did.

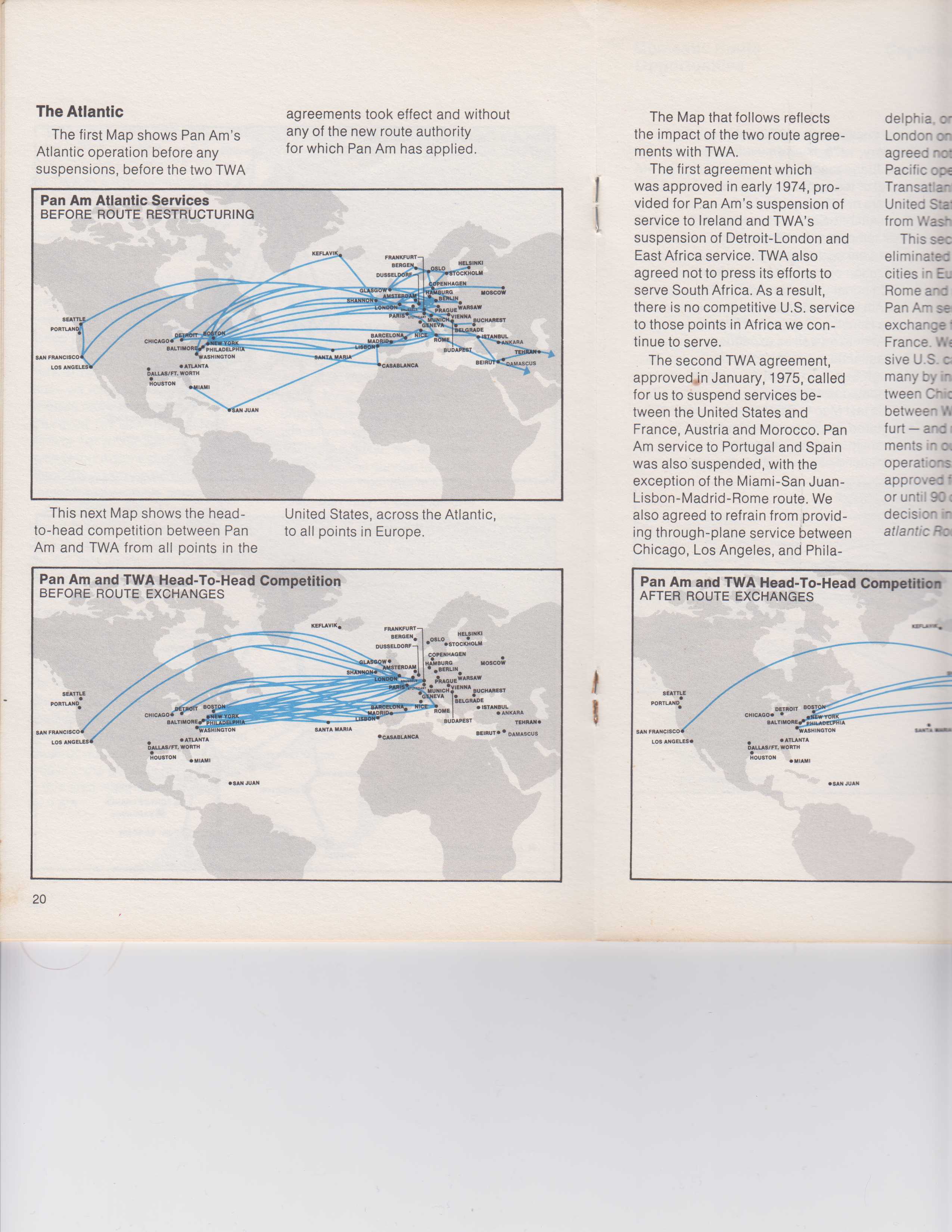

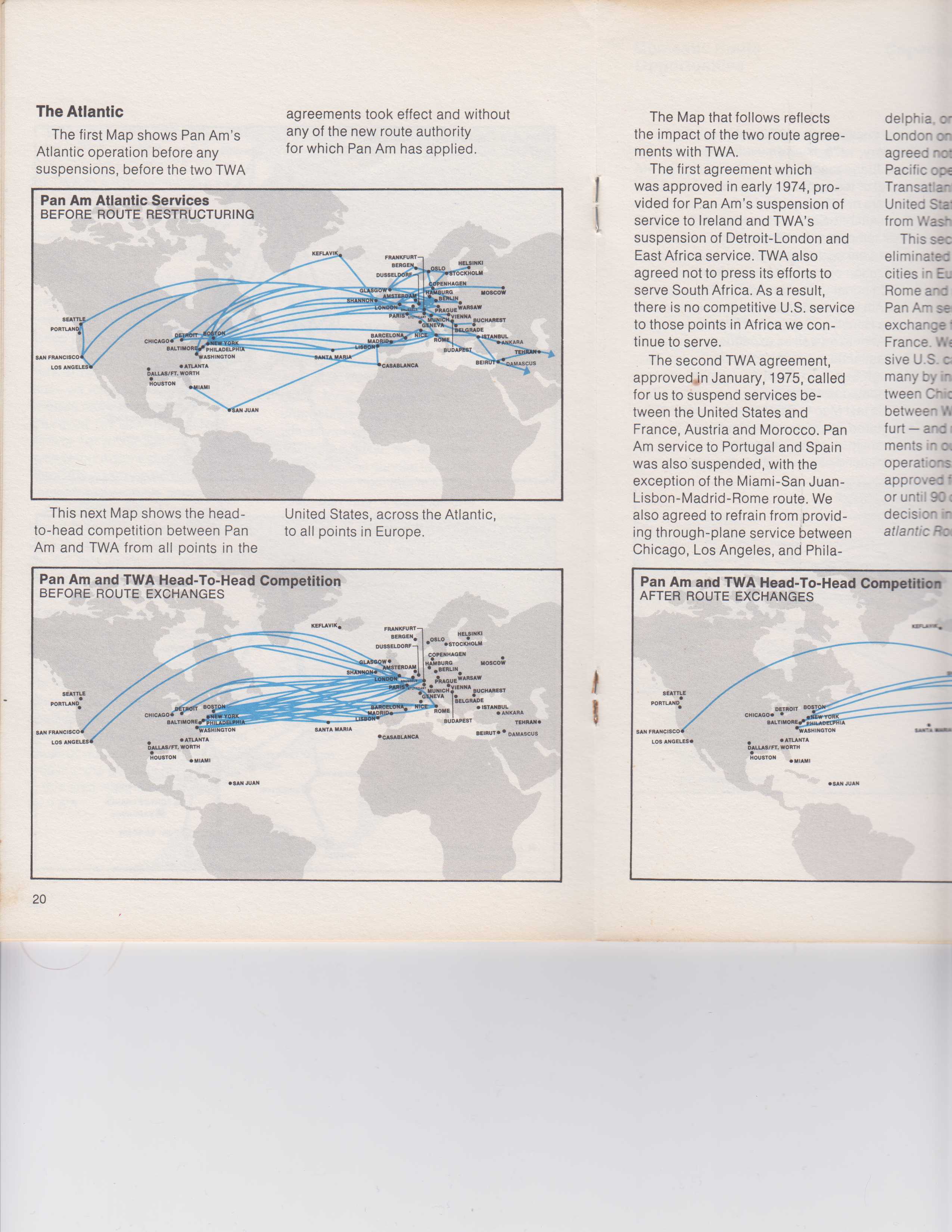

Another possibility would have been to merge with TWA. TWA and Pan Am had discussed merging several times in the past. After the most recent merger talks failed in 1974, the two airlines agreed instead to rationalize their international route systems. After the rationalization was completed, the only foreign cities where Pan Am and TWA competed against each other were London and Rome. The lack of overlap between the two airlines might have overcome the anti trust objections to past attempts to combine the airlines. Any remaining anti trust objections to a Pan Am + TWA merger could have been overcome by selling one of the two airlines’ London routes.

However, George Drury’s “late in life marriage” analogy would have applied just as much to a Pan Am + TWA merger as it did to an Eastern + National merger. A merged Pan Am + TWA would have created a global airline fed by a strong US domestic route system. The merged airline would also have inherited a very serious fleet problem, because both Pan Am and TWA had large numbers of obsolete 707s. Both airlines also had a vast network of reservations centers and ticket offices all over the world, headquarters buildings a few blocks from each other in Manhattan, and expensive separate terminals and hangars in cities like New York City, Los Angeles and San Francisco. The merged airline would have needed to move quickly to eliminate duplicate facilities and lay off unneeded management personnel, or the costs of the excess employees and real estate would have become a serious cash drain. Had a merged TWA + Pan Am not aggressively reduced overhead and modernized the combined airline’s fleet, all the merger would have accomplished would have been to take two troubled mid sized airlines, and combine them into one gravely ill large airline.

A third course for Pan Am, which the airline seriously considered after it became apparent that the National merger was a failure, would have been to shrink the airline down to only its most profitable routes: Latin America, Japan, and Germany. Doing this would have resulted in ¾ of the airline’s employees being furloughed, and much of its fleet being grounded, and it’s unlikely that this would have been a long term solution for Pan Am’s problems.

The best course for Pan Am if Texas International had merged with National, though, would have been for Pan Am’s management to recognize that it would be very difficult to obtain a profitable domestic feeder system through a merger or by building one from scratch – and accept that Pan Am’s international routes would be under attack as US domestic airlines expanded overseas post-deregulation and fed their new international routes with the passengers from their domestic routes that they’d previously been providing Pan Am.

Once Pan Am’s management recognized this, the next step would have been to preserve the jobs of Pan Am’s employees, and the money Pan Am’s lenders and shareholders invested in the airline, by selling Pan Am’s routes and aircraft to US domestic airlines that wanted to expand overseas. The asset sales would have come with the requirement that the airlines purchasing Pan Am’s routes also had to take Pan Am’s employees – which United and Delta agreed to when they purchased Pan Am’s Pacific and Atlantic routes after Pan Am began selling assets in a last ditch effort to avoid liquidation.

Had Pan Am broken itself up, United would have been the logical buyer for Pan Am’s Pacific routes. Northwest was awarded Pan Am’s routes to Scotland and Scandinavia in 1977, and they would probably have also been interested in the remainder of Pan Am’s European route system. The ideal buyer for Pan Am’s Latin American routes is less clear. Braniff, the other US airline that flew to Latin America, was on the verge of shutting down. Eastern, the airline that took over Braniff’s Latin American routes, would also have been on the brink of insolvency due to competition from Texas International + National. Although Delta would have been damaged by competition from Texas International + National, they could still have purchased Pan Am’s Latin American routes, as, ironically, could have Texas International + National itself.

If Pan Am had broken the airline up, its shareholders would have been left with the Inter Continental hotel chain and the Pan Am building in New York City, plus the cash other airlines paid for Pan Am’s routes and aircraft; the airline would, in effect, have turned itself into a very profitable real estate investment trust. Pan Am’s employees would have had jobs at other airlines, where they could have worked until retirement. It would have been a bittersweet end to the world’s most experienced airline…..but a much happier ending than the fate that befell Pan Am’s employees and shareholders when the airline shut down and liquidated in 1991.