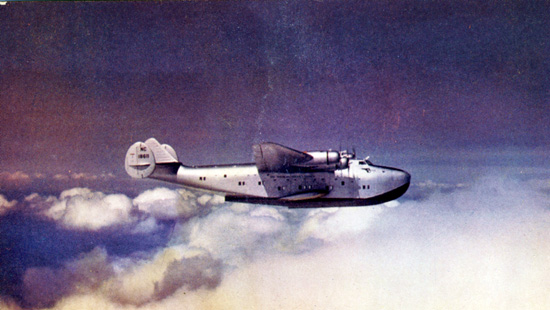

The Grumman G-21 Goose

Written by Robert G. Waldvogel

Although Long Island indigenous Grumman Corporation never produced a bonafide “airliner,” one of its designs enjoyed limited commercial success.

Founded by Leroy Randle Grumman, who was once plant manager of the Loening Aircraft and Engineering Corporation, the Grumman Aircraft and Engineering Corporation planted its initial roots in Baldwin, NY on January 2, 1930. As the years went by the company moved to progressively larger facilities—first to Valley Stream eight miles away, then to the Fairchild Flying Field, 16 miles away in Farmingdale, and finally to the sprawling Bethpage plant on April 8, 1937. The need for even more space prompted the opening of a secondary location at the United States Naval Air Facility “Peconic River” plant, in 1953.

Principally a supplier to the Navy, Marines, and Coast Guard, Grumman produced its famous F2F, F3F, F4F Wildcat, F6F Hellcat, F7F Tigercat, F8F Bearcat, F9F Panther and Cougar, F11F Tiger, TBF Avenger, and F-14 Tomcat series, most of which were instrumental in the victorious conclusion of several wars.

The G-21 Goose, the first of its aircraft that saw commercial service, was also the company’s first monoplane.

“In 1936, the Grumman Aircraft Corporation of Bethpage was approached by several wealthy Long Island residents who needed a small plane for personal transportation,” according to Long Island aviation historian Joshua Stoff, “They wanted an aircraft large enough to carry their families and baggage on trips, luxurious enough to fit their business needs, and flexible enough to take off and land either from the land or the sea.”

These residents’ selection of Grumman was the result of a referral. The initial request was to Loening for a successor to its Air Yacht and Commuter amphibians. Since he did not possess the facilities to undertake the project, Loening, who himself was a Grumman consultant, recommended them. Work on Design 21 began in 1936.

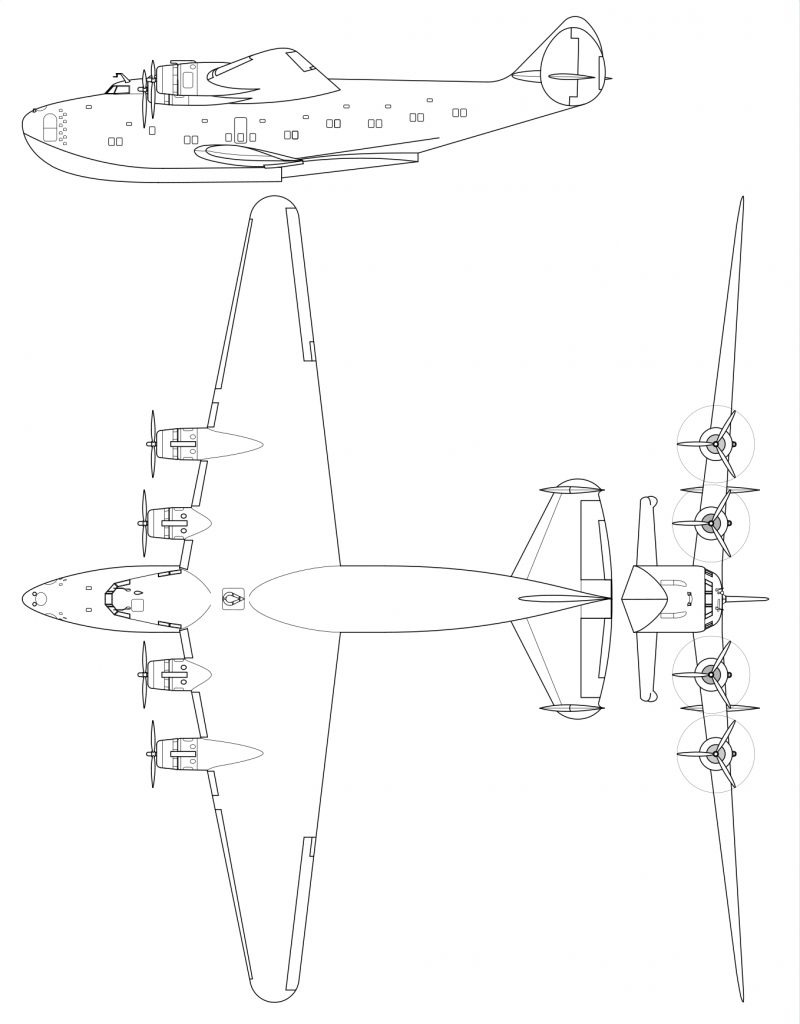

Representing transitional technology, the resulting design featured a riveted aluminum structure with a 38.3-foot overall length; a high-mounted wing, which had a 49-foot span and 375-square-foot area (but incorporated aft, fabric-covered sections and control surfaces), two outboard wing floats, and two nine-cylinder, 450-hp Pratt and Whitney Junior radials attached to the wing’s leading edge. Additional design features included a two-step hull for aquatic surface operations; a conventional tail; two single-wheel, upward-retracting main wheels for nesting in the fuselage sides; and a tail wheel.

The enclosed cabin, located behind the two-person cockpit, accommodated up to eight and was entered by an aft, port door. Convenience in flight was provided by a small galley and a lavatory. Baggage compartments were in the nose and behind the cabin.

When it first flew on May 29, 1935, The G-35 “Goose” became Grumman’s first twin-engine, land and water design, and the first with significant civil and commercial application.

The 65-minute inaugural flight from Bethpage, with a Manhasset Bay landing for demonstration purposes, led to type certification four months later, on September 29. The G-35’s max gross weight was 7,500 pounds. The type’s cruise speed was 175 mph and its payload- and fuel-determined range varied from 795 to 1,150 miles.

“The ease of handling, good stability, and satisfactory performance demonstrated during trials soon made the Goose a very popular aircraft with civil and military customers alike,” according to Rene J. Francillon in Grumman Aircraft since 1929. “Moreover, it proved to have a very strong airframe, thus endowing many of the 345 aircraft built by Grumman between May 1937 and October 1945 with a long service life.”

The G-35’s reasonable $60,000 price tag did not deter orders.

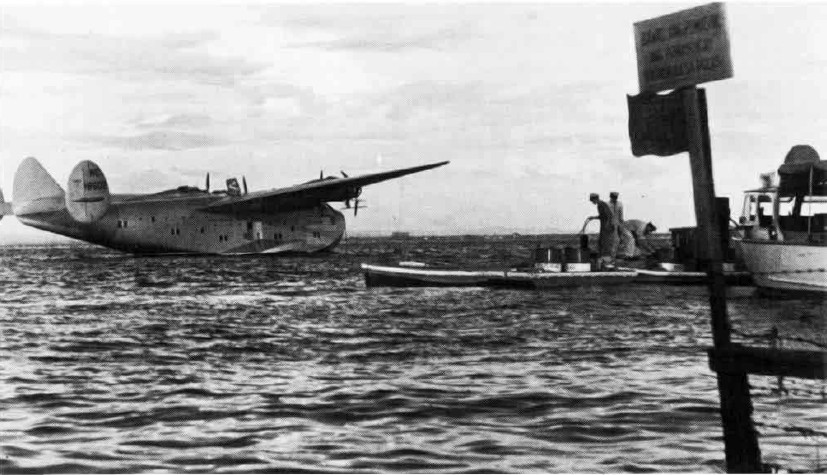

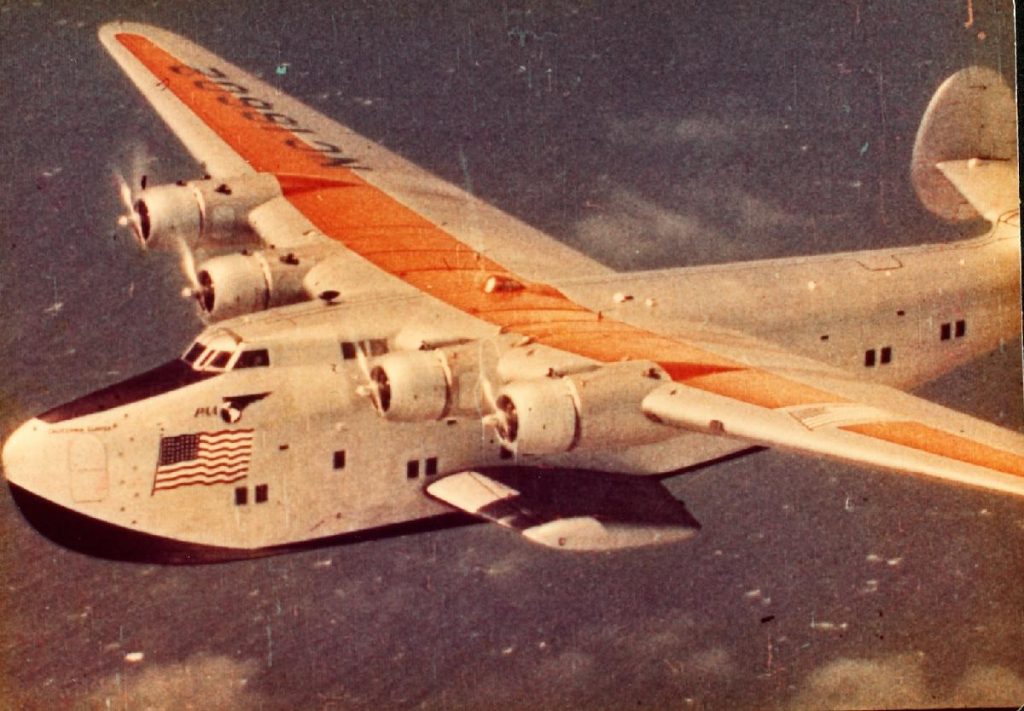

Aside from providing, as intended, comfortable transportation from water-front Long Island mansions to Wall Street and being used for similar, private purposes in the rest of the country, Canada, and the UK, this forerunner of the modern corporate jet had commercial application, as indicated by KNILM’s, KLM’s East Indian subsidiary, operation of it in March of 1940.

Bob Reeve, who amassed experience connecting Anchorage and Cold Bay during World War II, began regularly scheduled service to the Aleutian Islands in April of 1948 as Reeve Airways with a motley fleet of Long Island-originating aircraft, including the G-21 Goose and the Fairchild 71, (along with Douglas DC-3s and Sikorsky S-43s).

In the Caribbean, St. Croix-based Antilles Air Boats operated 18 G-21s, linking several islands as of February 1964, with service continuing all the way into the early 1980’s, and Mackey Airlines connected Miami with the Bahamas using its own G-21As until Eastern acquired the company in 1967.

Two carriers also used the type for the short, 21-mile hop from the California coast to Catalina Island—Avalon Air Transport from Long Beach and Catalina Seaplanes from San Pedro Harbor.

Grumman G-21 Goose Images from Wiki Commons